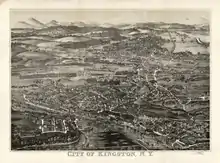

Kingston, New York

Kingston is the only city in, and the county seat of, Ulster County, New York, United States. It is 91 miles (146 km) north of New York City and 59 miles (95 km) south of Albany. The city's metropolitan area is grouped with the New York metropolitan area around Manhattan by the United States Census Bureau.[2] The population was 24,069 at the 2020 United States Census.[3]

Kingston, New York | |

|---|---|

| City of Kingston | |

Stockade District | |

%252C_New_York_Flag.png.webp) Flag  Seal | |

_highlighted.svg.png.webp) Location in Ulster County and the state of New York. | |

Kingston  Kingston | |

| Coordinates: 41°55′43″N 74°00′07″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| County | Ulster |

| Settled | 1652 |

| Village | April 6, 1805 |

| City | May 29, 1872 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Steve Noble (D) |

| • Common Council | Members' List |

| Area | |

| • City | 8.77 sq mi (22.71 km2) |

| • Land | 7.48 sq mi (19.38 km2) |

| • Water | 1.29 sq mi (3.33 km2) |

| Elevation | 191 ft (58 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 24,069 |

| • Density | 3,216.92/sq mi (1,242.00/km2) |

| • Metro | 177,749 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 12401-12402 |

| Area code | 845 |

| FIPS code | 36-39727 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0979119 |

| Website | kingston-ny |

Kingston became New York's first capital in 1777. During the American Revolutionary War, the city was burned by the British on October 13, 1777, after the Battles of Saratoga. In the 19th century, it became an important transport hub after the discovery of natural cement in the region. It had connections to other markets through both the railroad and canal connections.

Many of the older buildings are considered contributing as part of three historic districts, including the Stockade District uptown, the Midtown Neighborhood Broadway Corridor, and the Rondout-West Strand Historic District downtown. Each district is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

History

Dutch RepublicEmpire 1654–1664

British Empire 1664–1776

United States 1776–present

| New Netherland series |

|---|

| Exploration |

| Fortifications: |

| Settlements: |

| The Patroon System |

|

| People of New Netherland |

| Flushing Remonstrance |

|

_(14776657215).jpg.webp)

Colonial history

Kingston is the traditional home of the Esopus people. As early as 1614, the Dutch had set up a factorij (trading post) at Ponckhockie, at the junction of the Rondout Creek and the Hudson River. They traded European goods with the Lenape and Mohican for the furs their trappers collected. In 1652, the Indians of Ulster County ceded some land to the Dutch in what is now known as Kingston. The first recorded permanent settler in what would become the city of Kingston was Thomas Chambers. He came from the area of Rensselaerswyck in 1653. The new settlement was called Esopus after the local Lenape people.

In 1654, European settlers began buying more land from the Esopus Indians further west. However, historians believe the two cultures had drastically different conceptions of property and land use, causing tension between the two cultures as a result.Common sources of friction between Dutch settlers and the Esopus included settlers' livestock trampling Indian cornfields, disputes over trade, and the adverse effects of Dutch brandy on the Native Americans. Prior to the Europeans' arrival, they had no experience with liquor.

In the spring of 1658, Peter Stuyvesant, Director-General of New Amsterdam, ordered the consolidation and fortification of the settlement on high ground in what today is Uptown Kingston. The building of the defensive stockade increased the conflicts. Tensions broke out in the Esopus Wars.[4]

In 1661, the Dutch granted a charter for the settlement as a separate municipality; Stuyvesant named it Wiltwijck (Wiltwyck).[5] In 1663, the Esopus were defeated in the Second Esopus War by a coalition of Dutch settlers, and Wappinger and Mohawk peoples.

When the Dutch ceded their New Netherland to the British in September 1664, the British people worked to settle boundaries and conflict between the Europeans and the Esopus. Ultimately, the Richard Nicolls/Esopus Indian Treaty (1665) resulting in lasting peace between the settlers. According tot the treaty, the Esopus "in the names of themselves and theire heirs forever, give, Grant, Alienate, and Confirme all their Right and Interest, Claime or demand, to a certaine Parcell of Land" including the city of Kingston and extending to modern Kerhonkson. In exchange, the natives received "forty Blanketts, Twenty Pounds of Powder, Twenty Knives, Six Kettles, [and] Twelve Barrs of Lead" and "three laced redd coates" as a gift to the tribal leaders. Further, the British and Esopus designed a system of trade which included a protected trade path for the Esopus to travel unharmed, and a safe house where Esopus could stay when visiting the village. The treaty was respected for generations, as evidenced by records of annual gatherings between the Esopus and local Kingstonians where each exchanged gifts of mutual respect.[6]

Wiltwyck was one of three large Hudson River settlements in New Netherland, the other two being Beverwyck, now Albany; and New Amsterdam, now New York City. With the English seizure of New Netherland in 1664, relations between the Dutch settlers and the English soldiers garrisoned there were often strained. In 1669, the English renamed Wiltwyck as Kingston, in honor of the family seat of Governor Lovelace's mother.[5] In 1683, citizens of Kingston petitioned the Kingston court to buy more land from the Esopus people. Officials from Ulster County maintained contact with the Esopus until 1727.[7]

Many descendants of the Esopus people who inhabited the area became remnant members of several other related, displaced tribes. Some in the diaspora are among the federally recognized Stockbridge–Munsee Community, who moved from New York to Shawano County, Wisconsin; the Munsee-Delaware of the Six Nations Reserve in Ontario, Canada, established after the Revolution by the Crown for its Iroquois and other Indian allies; and the Ramapough Lenape Indian Nation (located primarily in the highland of the New York-New Jersey border area).

In 1777, Kingston was designated as the first capital of the state of New York. During the spring of 1777, when the New York State constitution was being written in White Plains, New York City was occupied by British troops. The work was moved to Kingston, which was deemed safer, and the document completed that April 20. It was never submitted to the people for ratification, but the first governor of the state, George Clinton, was sworn in as the first Governor of New York on July 30, 1777.[8]

The British never reached Albany, having been stopped at Saratoga, but they did reach Kingston. On October 13, 1777, the city was burned by British troops[9] moving up river from New York City, and disembarking at the mouth of the Rondout Creek at "Ponckhockie". The residents of Kingston knew about the oncoming fleet. By the time the British arrived, the residents and government officials had removed to Hurley, New York. The Kingston area was largely agricultural and a major granary for the colonies at the time, so the British burned large amounts of wheat and all but one or two of the buildings. Kingston celebrates and re-enacts the 1777 burning of the city by the British every other year in a citywide theatrical staging of the event that begins at the Rondout.

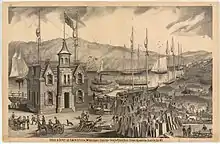

Kingston was incorporated as a village on April 6, 1805. In the early 1800s, four sloops plied the river, carrying passengers and freight from Kingston to New York. By 1829, river steamers made the trip to Manhattan in a little over twelve hours, usually travelling by night. Columbus Point (now known as Kingston Point) was the river landing for Kingston, and stage lines ran from the village to the Point.[10] The Dutch cultural influence in Kingston remained strong through the nineteenth century.

Rondout

Rondout was a small farming village until 1825, when construction of the Delaware and Hudson Canal from Rondout to Honesdale, Pennsylvania, attracted an influx of laborers. When they completed the canal in 1828, Rondout became an important tidewater coal terminal. Natural cement deposits were found throughout the valley, and in 1844 quarrying began in the "Ponchockie" section of Rondout. The Newark Lime and Cement Company shipped cement throughout the United States, a thriving business until the invention of cheaper, quicker drying Portland Cement. Workers cut and stored ice from the Hudson River each winter, keeping it in large warehouses of ice near the river. The ice would be cut in chunks and delivered to customers around the city. It was preserved in straw all year and ice chunks served as an early method of refrigeration.[11]

Large brick making factories also were built near this shipping hub.[12][13] Rondout's primacy as a shipping hub ended with the advent of railroads. These lines were built through Rondout and Kingston, with stations in each place. They could also transport their loads through the city without stopping.

Wilbur

Wilbur (aka Twaalfskill) was a hamlet upstream from Rondout, where the Twaalfskill Creek met the Rondout Creek. There was a sloop landing there. The hamlet became the center for the shipment of bluestone to lay the sidewalks of New York City.

Kingston officially became a city on May 29, 1872, with the merger of the villages of Rondout and Kingston, and the hamlet of Wilbur.[14]

Historic churches

Fair Street Reformed Church

The congregation of the Fair Street Reformed Church meets in the oldest public worship building in Kingston. Established as the Second Reformed Church of Kingston in January 1849, the small group of 27 people originally met for worship in the County Court House on Wall Street. In 1850 construction of the church began, using local dolomite limestone taken from a quarry on upper Pearl Street. The church was originally graced by a steeple purported to be the highest of its time out of New York City.

Old Dutch Church

Kingston is home to many historic churches. The oldest is the First Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of Kingston, which was organized in 1659. Referred to as The Old Dutch Church, it is in uptown Kingston. George Clinton, first governor of New York and fourth US vice president, is buried in the churchyard. Many of the city's historic churches are on Wurts street (six are in one block). What is now called the Hudson Valley Wedding Chapel was built in 1867; it has been restored and is used for weddings.

Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church

Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church at 75 Spring Street was founded in 1842. The original church building at the corner of Hunter and Ravine streets burned to the ground in the late 1850s. The current church on Spring Street was built in 1874.[15]

St. John's Episcopal Church

St. John's Episcopal Church was named for St. John the Evangelist. It was founded in 1832, on June 24, the feast of St. John the Baptist. Therefore, both are considered patrons of the parish. Rev. Reuben Sherwood of Saugerties, New York was the first rector. The first church was built on Wall Street and opened November 24, 1835.

In 1926, the property was sold to the Up-to-Date clothing company. The church structure was dismantled and relocated to Albany Ave.[16] In 1992, St. John's established "Angel Food East", a ministry that delivers food prepared at the church kitchen to persons in need throughout Ulster County.[17]

Church of the Holy Cross

In 1891, Lewis T. Wattson, rector of St. John's, established the Church of the Holy Cross as a mission of St. John's, to serve working-class families living near the West Shore Railroad. Many of them worked for the railroad.[18] Holy Cross had a more Anglo-Catholic tradition and a particular mission to the poor.[19] Since the late 20th century, given increased Latino immigration from Mexico, Central and South America, Holy Cross/Santa Cruz has become a bilingual (Spanish/English), multicultural Episcopal parish.

St. Joseph's Roman Catholic

St. Joseph's Parish began in 1863 as a one-room Roman Catholic mission school to serve the children of the Wilbur area. It was founded by Father Felix Farrelly, pastor of St. Mary's Parish in Rondout. The building was later sold to the city of Kingston in 1871.[20]

In 1867, Rev. James Coyne was appointed pastor of St. Mary's in Rondout. The following year he established St. Joseph's in Kingston. He purchased the Young Men's Gymnasium on the corner of Fair and Bowery streets. The first Mass was said on September 21, 1868, by Fr. James Dougherty, an alumnus of St. Mary's parochial school. Dougherty became the first pastor of St. Joseph's parish.[20] Fr. Dougherty is buried in St. Mary's Cemetery.

As the chapel was deemed too small, the parish purchased the former Kingston Armory at the corner of Wall and Main streets for use as a church. Many new Catholic immigrants had arrived in the mid-century from Ireland and southern and eastern Europe. The new church was dedicated on July 26, 1869. In 1877 Jockey Hill was made a mission of St. Joseph's. In 1962 a mission was established in Hurley.

In 1893, St. Joseph's Church underwent a major renovation, including the installation of the side altars. The new church front was completed in 1898. The interior was renovated in 1905.[20]

The frame building on the Bowery was adapted as a schoolhouse. This was replaced in 1905 with the acquisition of the former mansion of Judge Alton B. Parker at 1 Pearl Street, for a new St. Joseph's School and Convent. The Fair Street school building continued to be used as the parish hall until the property was sold in 1911.[21] Also in 1911 a site for a larger school and convent was secured and 1 Pearl Street was sold. In 1943 the Sisters of St. Ursula replaced the Sisters of Charity at the school.

In February 1962, construction began on the current St Joseph School, which housed eight additional classrooms. Old St. Joseph School was renamed as the Msgr. Stephen Connolly Bldg. A plaque donated by the Holy Name Society in honor of Father John Broidy, the pastor who oversaw construction of the building in 1912, is installed on the right front of the building.[22]

A.M.E. Zion Church of Kingston

The A.M.E. Zion Church of Kingston (previously known as Franklin Street AME Zion Church) is an African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church established in 1848. Its current building at 26 Franklin Street was completed in 1929. It also owns the historic Mount Zion Cemetery.

Geography and culture

Kingston has three recognized area neighborhoods. The Uptown Stockade Area, The Midtown Area, and The Downtown Waterfront Area. The Uptown Stockade District was the first capital of New York State. Meanwhile, the Midtown area is known for its early 20th century industries and is home to the Ulster Performing Arts Center and the historic City Hall building.

The downtown area, once the village of Rondout and now the Rondout-West Strand Historic District, borders the Rondout Creek and includes a recently redeveloped waterfront. The creek empties into the Hudson River through a large, protected tidal area which was the terminus of the Delaware and Hudson Canal, built to haul coal from Pennsylvania to New York City.[23]

The Rondout neighborhood is known for its artists' community and its many art galleries; in 2007 Business Week online named it as among "America's best places for artists."[24] It is also the site of a number of festivals, including the Kingston Jazz Festival and the Artists Soapbox Derby.[25]

Midtown is the largest of Kingston's neighborhoods, home to Kingston High School, an original Carnegie Library that is currently part of the high school, and both campuses of HealthAlliance Hospital, part of the Westchester Medical Center Health Network; HealthAlliance Broadway Campus (formerly The Kingston Hospital) and HealthAlliance Mary's Avenue Campus (formerly Benedictine Hospital).

While the Uptown area is noted for its "antique" feeling, the overhangs attached to buildings along Wall and North Front streets were added to historic buildings in the late 1970s and are not authentically part of the 19th century Victorian architecture. The historic covered storefront walks, known as the Pike Plan, were recently reinforced and modernized with skylights. In the Stockade district of Uptown, many 17th century stone buildings remain. Among these is the Senate House, which was built in the 1670s and was used as the state capitol during the revolution. Many of these old buildings were burned by the British Oct. 17, 1777, and restored later. A controversial restoration of 1970s-era canopies was marred by the sudden appearance of painted red goats on planters just prior to the neighborhood's rededication.[26] This part of the city is also the location of the Ulster County Office Building.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 8.6 square miles (22 km2), of which 7.3 square miles (19 km2) is land and 1.3 square miles (3.4 km2), or 15.03%, is water. The city is on the west bank of the Hudson River. Neighboring towns include Hurley, Saugerties, Rhinebeck, and Red Hook.

The city's Hasbrouck Park was created in 1920; it is 45 acres (18 ha) in area and includes a nature trail.

Sidewalks with porticos in the Stockade District uptown

Sidewalks with porticos in the Stockade District uptown Historic commercial buildings in Kingston

Historic commercial buildings in Kingston Downtown Kingston, called The Rondout

Downtown Kingston, called The Rondout

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 6,315 | — | |

| 1880 | 18,344 | 190.5% | |

| 1890 | 21,261 | 15.9% | |

| 1900 | 24,535 | 15.4% | |

| 1910 | 25,908 | 5.6% | |

| 1920 | 26,688 | 3.0% | |

| 1930 | 28,088 | 5.2% | |

| 1940 | 28,589 | 1.8% | |

| 1950 | 28,817 | 0.8% | |

| 1960 | 29,260 | 1.5% | |

| 1970 | 25,544 | −12.7% | |

| 1980 | 24,481 | −4.2% | |

| 1990 | 23,095 | −5.7% | |

| 2000 | 23,456 | 1.6% | |

| 2010 | 23,893 | 1.9% | |

| 2020 | 24,069 | 0.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[27] | |||

As of the 2010 census, the city had 23,887 people, 9,844 households, and 5,498 families. The population density was 3,189.5 persons per square mile (1,231.5 persons/km2). There were 10,637 housing units at an average density of 1,446.4 houses per square mile (558.5 houses/km2). The city's racial makeup was 73.2% White, 14.6% Black or African American, 0.50% Native American, 1.80% Asian, 1.90% from other races, and 5.00% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 13.4% of the population.

As of the 2000 census there were 9,871 households, out of which 27.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.2% were married couples living together, 15.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 44.3% were non-families. 36.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.28 and the average family size was 3.02.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 23.9% under the age of 18, 8.1% from 18 to 24, 28.9% from 25 to 44, 21.9% from 45 to 64, and 17.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.1 males.

The city's median household income was $31,594, and the median family income was $41,806. Males had a median income of $31,634 versus $25,364 for females. The city's per capita income was $18,662, with 12.4% of families and 15.8% of the population below the poverty line, including 23.5% of those under age 18 and 10.3% of those age 65 or over.

Sports

The Kingston Tigers are the city high school's sports teams.

Kingston Stockade FC is a men's semi-professional soccer club that competes in the National Premier Soccer League in the fourth division of the US soccer pyramid. Kingston Stockade FC play their home games at Dietz Stadium.[28]

In 1921, one time major league player Dutch Schirick organized a semi-professional team, the Colonels, in Kingston, New York. Major league teams would, on occasion, play exhibition games against the Kingston Colonels, and would sometimes recruit local talent. Bud Culloton became a pitcher for the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Government

The government of Kingston consists of a mayor and city council known as the Common Council. The Common Council consists of 10 members, nine of which are elected from wards while one is elected at large. The mayor is elected in a citywide vote every four years.

Steve Noble was elected to the mayoral post in 2015.[29]

List of notable mayors:

| Name | Years Served | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| James Girard Lindsley | 1872-1877 | Lindsley Street named for him |

| William Lounsbery | 1878-1879 | Lounsbery Place named for him |

Education

- The Kingston City School District contains seven elementary schools, two middle schools, and one high school.

- Kingston High School is the city's public high school

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York operates Catholic schools in Ulster County. John A. Coleman Catholic High School closed in 2019.[30] Kingston Catholic School is also in the community.

St. Joseph School in Kingston had 267 students in 2007.[31] It was originally scheduled to close in 2013. However the archdiocese reversed course and allowed it to stay open.[32] However, in 2017 the school ultimately did close.[33] By spring 2017 the school had 146 students. The would-be enrollment had dropped to 90 for the 2017–2018 school year. Kingston Catholic School acquired the newer St. Joseph building and turned it into its middle school facility.[31] The older building was put up for sale in 2019.[34]

The Kingston Center of SUNY Ulster (KCSU) is a branch of the county's community college that offers programs, courses and certifications at a convenient Midtown location. KCSU is the new home for Police Basic Training and also offers human services, criminal justice and the general education courses required by the State of New York to satisfy the liberal arts core of an A.A. or A.S. degree.[35]

Media

- Newspapers

- Kingston-based: Daily Freeman, Kingston Times

- Outside Kingston: Art Times, Poughkeepsie Journal, Times-Herald Record (Middletown)

- See also: List of newspapers in New York in the 18th-century: Kingston

- Television:

- Time Warner Cable Kingston Area Public-access television cable TV channel 23

- WRNN-TV channel 62 was founded in and formerly licensed to Kingston as WTZA, but its commitment to the area wavered in and out before it moved its main studio downstate to Rye Brook in 2006 and shifted its city of license to New Rochelle in 2018; it currently carries ShopHQ nearly full-time with no regional-specific programming

- Radio

- Magazines: Chronogram, Trends Journal

- Music festivals: O+ Festival

- Blogs: The Kingston News, Kingston Creative, and Kingston Happenings

Infrastructure

Transportation

Commuter service is available by bus to New York City daily via Trailways of New York. The 90-mile trip takes roughly two hours by motor coach.

Passenger railroad service to Kingston Union Station was discontinued in 1958 when the New York Central Railroad ended passenger service on the West Shore Railroad, which ran on an Albany—Kingston—Newburgh—Weehawken, New Jersey itinerary. Amtrak maintains service on the east side of the Hudson. The Rhinecliff–Kingston Amtrak station is about 11 miles (20 km) away, and there is also access to Amtrak at the Poughkeepsie station, on the east bank of the Hudson and about 17 miles (30 km) south. That station also serves as the northernmost terminus for Metro-North commuter trains.

CSX Transportation operates freight rail service through Kingston on the River Line Subdivision. A small rail yard containing seven tracks is operated in Kingston.

The Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge, 4.32 miles (6.95 km) to the north, carries New York State Route 199 and is the nearest bridge traversing the Hudson River. U.S. Highway 9W runs north–south through the city. The New York State Thruway, carrying the Interstate 87 designation through this section, runs through the western part of the city.

The area is served by Kingston–Ulster Airport, located at the western base of the Kingston–Rhinecliff bridge. The nearest major airports to Kingston are Stewart International Airport 39 miles (62.8 km) south in Newburgh, and Albany International Airport, approximately 65 mi (105 km) north.[36] The three major metropolitan airports for New York City are located on western Long Island (LaGuardia Airport, approximately 80 mi (129 km) south and John F. Kennedy International, approximately 93 mi (150 km) south) and in New Jersey (Newark Liberty International,approximately 86 mi (138 km) south).

Local travel was supported by the city-owned CitiBus system (headquarters at 420 Broadway) provides city bus service, and Ulster County Area Transit (UCAT) provides service to points elsewhere in Ulster County. Route A travels between Kingston Plaza and Riverfront, B between Albany Avenue and Fairview Avenue, and C between Golden Hill and Port Ewen. The service was taken over by UCAT in 2019.[37]

Weekend water taxi service between Kingston and Rhinecliff, New York is available May through October for $10 round-trip.[38] Some trips stop at the Rondout Light; a tour is available for an additional $5.[39]

Kingston historically was an important transportation center for the region. The Hudson River, Rondout Creek and Delaware and Hudson Canal were important commercial waterways. At one time, Kingston was served by four railroad companies and two trolley lines. Kingston has been designated as a New York State Heritage Area, with a transportation theme. The Hudson River Maritime Museum and Trolley Museum of New York are located along the waterfront and help interpret this historic role.

The Catskill Mountain Railroad, a scenic railroad company, runs trains from Kingston to West Hurley on the former Ulster and Delaware right of way.

As of 2016, more than a dozen projects were being coordinated among the Kingston Land Trust, Kingston City Government, and Ulster County Government, which will connect all three of Kingston's historic neighborhoods with a combination of rail trails, bike lanes and Complete Streets connections.[40]

Healthcare

Residents of the city and surrounding areas are served by the two hospital campuses of HealthAlliance of the Hudson Valley, a 315-bed healthcare system:

- HealthAlliance Hospital: Broadway Campus (formerly Kingston Hospital)[41]

- HealthAlliance Hospital: Mary's Avenue Campus (formerly Benedictine Hospital)

HealthAlliance is part of the Westchester Medical Center Health Network, a 10-hospital, 1,700-bed Hudson Valley-wide healthcare system.

There are also multiple urgent care sites, private practice offices and laboratories in the city and surrounding area.

Notable people

References

- "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- New York-Newark, NY-NJ-CT-PA Combined Statistical Area Archived 2014-12-29 at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 28, 2014.

- "Census - Geography Profile: Kingston city, New York". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- Smith, Jesse (2005). "Esopus Wars were 'the clash of cultures'". Daily Freeman. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019.

- Schoonmaker, Marius (1888). "Schoonmaker, Marius. The History of Kingston, Burr Print. House, Kingston, NY 1888". Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- Ulster County Clerk’s Office Records Management Program—Archives Division (2015). "An Agreement made between Richard Nicolls Esq., Governor and the Sachems and People called the Sopes Indyans 7th day of October 1665" (PDF). Ulster County Clerk’s Office Records Management Program—Archives Division. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 4, 2023. Retrieved September 4, 2023.

- "Relations between the Huguenots of New Paltz, N. Y. and the Esopus Indians". Archived from the original on September 27, 2010.

- "NYS Kids Room - State History". New York State Department of State. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- "Burning of Kingston". New York Packet. October 23, 1777. Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- Clearwater, Alphonso Trumpbour (1907). "Hendricks, Howard. "Kingston", Clearwater, Alfonso Trumpbour. The History of Ulster County, New York, W. J. Van Deusen, Kingston NY, 1907". Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- "Close Of The Ice Harvest.; Nearly All The Houses Filled—The Largest Crop Ever Gathered". The New York Times. January 25, 1881. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- "Ulster Landing and East Kingston". brickcollecting.com. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- Rob Yasinsac. "Hudson Valley Ruins: East Kingston - Hudson Cement Company and Shultz Brick Yard by Rob Yasinsac". hudsonvalleyruins.org. Archived from the original on October 24, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- Steuding, Robert Rondout A Hudson River Port p. 155

- Confessore, Nicholas; Barbaro, Michael (June 25, 2011). "New York Clerks' Offices Gird for Influx of Gay Couples". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 3, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ""St. John's History", St. John's Episcopal Church". Archived from the original on August 29, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ""Our Mission", Angel Food East". Archived from the original on August 29, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- Murphy, Patricia O'Reilly (May 17, 2013). Kingston. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738598260 – via Google Books.

- ""History", Holy Cross Church". Archived from the original on August 29, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- "Our History". Archived from the original on May 20, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- Clearwater, Alphonso T. (2001). Burtsell, Richard Lalor. "The Roman Catholic Church", Clearwater, Alphonso Trumpbour. The History of Ulster County, New York, W. J. Van Deusen, 1907 - Ulster County (N.Y.). ISBN 9780788419430. Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- "St. Joseph Catholic School". Archived from the original on May 31, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- "Hudson River Maritime Museum". Archived from the original on January 8, 2008.

- Roney, Maya (February 26, 2007). "Bohemian Today, High-Rent Tomorrow". Bloomberg Business (formerly Business Week). bloomberg.com. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- "Kingston, NY: Profile Archived 2017-07-30 at the Wayback Machine". Forbes. Forbes.com. Retrieved 2017-07-01.

- Leonard, DB (November 23, 2011). "DB Leonard commentary: Goats go viral". Kingston Times. Ulster Publishing. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 7, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Home". Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- Horrigan, Jeremiah. "Steve Noble takes Kingston's top prize". recordonline. Dow Jones Local Media Group. Archived from the original on February 12, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- Kott, Crispin (August 9, 2019). "Falling enrollment means the end for Coleman Catholic high school".

- Kemble, William J. (June 1, 2017). "With St. Joseph's School closing, one of its two buildings will become part of Kingston Catholic School, archdiocese says". Daily Freeman. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "St. Joseph's School in Kingston to stay open after all, Archdiocese of NY says". October 15, 2017. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017.

- Schiffres, Jeremy (May 31, 2017). "St. Joseph's School in Kingston closing at end of current school year". Daily Freeman. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- Kirby, Paul (August 19, 2019). "Buildings that housed former St. Joseph's School, former convent up for sale". Daily Freeman. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- "Kingston Center of SUNY Ulster - SUNY Ulster". Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- "Traveler's Information". Ulster County. Archived from the original on August 21, 2006. Retrieved August 13, 2006.

- "City of Kingston, New York - Citibus". Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- "Kingston-Rhinecliff water taxi launches today". DailyFreeman.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2012. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- "The Lark: Hudson River Water Taxi". HudsonRiverCruises.com. Archived from the original on December 26, 2010. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- "5 New Reasons Why You Should Move to Midtown Kingston Right Now - Kingston Creative". Kingston Creative. April 29, 2016. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- "NORTHERN DUTCHESS HOSPITAL". Health Quest. Archived from the original on November 24, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2017.