Papaver heterophyllum

Papaver heterophyllum, previously known as Stylomecon heterophylla, and better known as the wind poppy, is a winter annual herbaceous plant. It is endemic to the western California Floristic Province and known to grow in the area starting from the San Francisco Bay Area of Central Western California southwards to northwestern Baja California, Mexico. Its main habitat is often described as mesic and shady, with loamy soils such as soft sandy loam, clay loam, and leaf mold loam.[1]

| Papaver heterophyllum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Wind poppy (Papaver heterophyllum) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Ranunculales |

| Family: | Papaveraceae |

| Genus: | Papaver |

| Species: | P. heterophyllum |

| Binomial name | |

| Papaver heterophyllum (Benth.) Greene | |

_(3482234378).jpg.webp)

It is a member of the family Papaveraceae, the poppy family of flowering plants mostly found in the Northern Hemisphere.[2] The name poppy originates from Early Old English popeġ, popaeġ, popæġ, or popei[3] and is suspected to have previously come from Late Latin papavum, popauer.[3]

Morphology

The wind poppy consists of radially symmetrical flowers supported by long, thin, and wiry stems with lobed leaves. The flower has bright orange petals and a purple-black central disk.[4] The central disk is a deep red which distally fades at the petal bases, while the staminal filaments are dark red to black. It is a relatively short lived annual herb with a blooming period that can occur from February to late May, with the peak occurring in March and April. The wind poppy is a polyploid, with reports on chromosome number for the species concluding it as being octoploid. It is also self compatible and autonomously self-pollinating.[1]

Papaver heterophyllum can be compared to Papaver californicum because of the close species relationship delineated by similar vegetative and reproductive traits. It was stated by Ernst in 1962 that the “seedling stages are identical, and even the adult plants are so similar that determinations cannot be made without the gynoecia.”[5] The species are more easily distinguishable through leaf, flower, and fruit morphology.

Kadereit & Baldwin describe the gynoecium of Papaver heterophyllum to have a flat ovary roof with capsules that split apart through pores under it. The seeds of Papaver heterophyllum have a mean length of 803 µm, with a coarser seed surface when compared to the smaller seeds of P. californicum.

As for leaf morphology, Papaver heterophyllum has a delicate “dissection” pattern on the middle and distal cauline leaves. It is thought that the name heterophyllum came from the observation of the distinctive sharp transition between the proximal and middle cauline leaf margins.[1]

Taxonomy

Subspecies

Papaver heterophyllum has no known subspecies.

Genus

Papaver heterophyllum resides under the genus Papaver, which contains over a 100 species and includes other poppy species, with the type species being the opium poppy, or Papaver somniferum.[6] Current studies do not support that Papaver is a monophyletic group.[7]

A phylogenetic systematics study in 2011 concluded that P. heterophyllum could hybridize with P. californicum, which favors a botanical name change from its previous one, S. heterophylla.[1] This conclusion occurred almost fifteen years after it was first postulated by one of the same investigators in 1997 that S. heterophylla arose from Papaver and should not be placed into a separate genus.[1]

The 2011 paper by Kadereit & Baldwin compared Stylomecon heterophylla (now known as Papaver heterophylla) to Papaver californicum. S. heterophylla is closely related to P. californicum, but because of differing gynoecium and fruit morphology, this relationship was unexpected. The gynoecium of P. californicum has a sessile stigmatic disc and below the disc are small valves where the capsules open. This morphology is typical of Papaver while the gynoecium of S. heterophylla has a style over an ovary roof and below the roof are pores by which the capsules open. This morphology, specifically gynoecia with a style, is usually found in the Meconopsis family which led the wind poppy to be placed in that family. DNA evidence, along with a comparison of vegetative and reproductive traits, has since indicated that S. heterophylla is actually in the Papaver genus.[1]

Family

Papaver heterophyllum falls under the family of Papaveraceae, which contains more than 825 species and 44 genera.[2]

Habitat

Papaver heterophyllum is native to the coastal mountains of central California down to Baja where it grows on the sides of slopes below altitudes of 4000 feet (1200 m).[8] They are often found in chaparral, grasslands and oak woodlands.[9] They prefer an environment with low moisture and well-drained soil in part shade[10] and are uncommon even within their range. They seem to survive a relatively broad range of environmental conditions, at least compared to P. californicum.[1]

Ecological relationships

They are annuals and bloom in the spring but are especially abundant after a fire because the seeds are cued to germinate by cues such as heat, smoke, or charred wood. Within its habitat, wind poppy flowers usually stand a little taller than most of the surrounding vegetation which is thought to help them sway in the wind to attract insect pollinators from further away.[10]

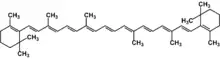

Carotenoids

The wind poppy is known for its bright orange color. This color results from the presence of carotenoids, organic pigments, in the flower,[10] although early studies have found that its flowers only contain a small amount of carotenoids.[11] These pigments are terpenoids often of the formula C40,[12] that absorb wavelengths of 400 to 550 nanometers.[13] These wavelengths correspond to the visible light spectrum from green to violet. Thus, the pigments reflect red to yellow light, giving the poppies their orange color.

Human use

The wind poppy is most often found in the wild, and rarely seeds except after wildfires.[14] While many poppy species are used medicinally across the world, the wind poppy is not known to be farmed, lauded for medicinal use, or consumed by humans.[10] However, wind poppy seeds are commercially sold, as the bright flower is thought to be appealing due to its bright color and lily-like scent.[15]

Hybrids

Since it is most often found in the wild and rarely seeds, there are no natural or manmade hybrids. There is seldom hybridization between the two species because successful reproduction requires P. heterophyllum to be the female parent. Kadereit & Baldwin attempted to hybridize P. heterophyllum and P. californicum (western poppy), which produced plants that developed well but were sterile.[1]

References

- Kadereit, Joachim W.; Baldwin, Bruce G. (2011-04-01). "Systematics, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Papaver californicum and Stylomecon heterophylla (Papaveraceae)". Madroño. 58 (2): 92–100. doi:10.3120/0024-9637-58.2.92. ISSN 0024-9637. S2CID 85288778.

- "Papaveraceae | Description, Characteristics, & Examples". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "poppy, n.", OED Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 2020-12-03

- "GSA Field Guide 2: Great Basin and Sierra Nevada". SciTech. 2. 2000. doi:10.1130/0-8137-0002-7. ISBN 0-8137-0002-7.

- "Ernst, Wallace Roy (1962) A comparative morphology of the Papaveraceae. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Biological | Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve". jrbp.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "Plant Article Orchids: Characteristics". www.ndsu.edu. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- CAROLAN, JAMES C.; HOOK, INGRID L. I.; CHASE, MARK W.; KADEREIT, JOACHIM W.; HODKINSON, TREVOR R. (2006-07-01). "Phylogenetics of Papaver and Related Genera Based on DNA Sequences from ITS Nuclear Ribosomal DNA and Plastid trnL Intron and trnL–F Intergenic Spacers". Annals of Botany. 98 (1): 141–155. doi:10.1093/aob/mcl079. ISSN 0305-7364. PMC 2803553. PMID 16675606.

- "Papaver heterophyllum Calflora". www.calflora.org. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "Wind poppy". www.calflora.net. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "Wind Poppy". Nature Collective. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- Strain, Harold H. (1938-04-01). "Eschscholtzxanthin: A New Xanthophyll from the Petals of the California Poppy, Eschscholtzia Californica". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 123 (2): 425–437. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)74131-8. ISSN 0021-9258.

- Nisar, Nazia; Li, Li; Lu, Shan; Khin, Nay Chi; Pogson, Barry J. (2015-01-05). "Carotenoid Metabolism in Plants". Molecular Plant. 8 (1): 68–82. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2014.12.007. ISSN 1674-2052. PMID 25578273.

- Xu, Yanan; Harvey, Patricia J. (2019-05-05). "Carotenoid Production by Dunaliella salina under Red Light". Antioxidants. 8 (5): 123. doi:10.3390/antiox8050123. PMC 6562933. PMID 31067695.

- "Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center - The University of Texas at Austin". www.wildflower.org. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "Wind Poppy - Stylomecon heterophylla". www.tradewindsfruit.com. Retrieved 2020-12-03.