Windenburg

Windenburg was a rather typical small castle in Dreischor, the Netherlands .

| Windenburg | |

|---|---|

Windenburg | |

| Dreischor, the Netherlands | |

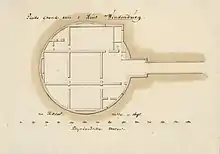

Windenburg in 1743 by C. Pronk | |

Windenburg | |

| Coordinates | 51.688471°N 3.981664°E |

| Type | Water castle |

| Site information | |

| Open to the public | No |

| Condition | Disappeared |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1397-1401[1] |

| Materials | brick |

| Demolished | 1837 |

Castle Characteristics

Phase 1: a strong small castle

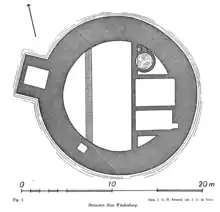

The Windenburg was a castle of a peculiar form.[2] The floor plan and depictions give the impression of a single round tower house. However, archaeological investigations showed that in its first phase, the circular structure had an inner courtyard. Therefore, the castle was a very small water castle. It consisted of a ring wall of about 17.5 m diameter,[3] a gatehouse at the front, and a wing with some rooms built alongside the wall in the back. The early 19th-century cadastre map shows that it was surrouned by a moat of about 20 m wide.

At the foundation level the ring wall was 2.45 m thick, which was very thick for a wall, but also for a tower house. The ring wall, gate house and habitation wing were built as one structure. The bricks used were 26–29 cm long with a thickness of 6.5 cm.[4] In the core of the ring wall there were many half or one-third bricks, and many showed signs of being re-used for this purpose.[5] A protected walkway would have been on top the wall, with its covering wall perhaps protruding a bit over the moat.[6]

The back wing had two square rooms on the basement level, which was vaulted.[7] North of these rooms, a quarter circle room held two ovens.[4] On top of the two square rooms, one can suppose a 'hall' of hardly 6 by 4.5 m.[6]

Later another heavy wall was built on the basement level. It ran in parallel to the courtyard façade of the back wing. That construction of this wall happened later is known from the seams in the masonry on both ends of this wall, and that this new wall prevented access to an area in the ring wall which was identified as a water well. Construction of the wall probably also led to the decommissioning of the ovens.[8] While treating the later renovation and Hildernisse's floor plan, Renaud concluded that construction of this wall was not part of the 1476-1478 renovation.[9] However, this judgement might have been made under the influence of not knowing much about Hildernisse's work.

A bailiff's residence

The setup of the castle might have been justified for military reasons. However, its decided lack of comfort, made Jaap Renaud conclude that it had not been built as house for a nobleman, but was probably built as a residence for a bailiff.[6]

Phase 2: an inhabitable castle

From 1476 to 1478 the Windenburg was renovated and changed. From accounts it's known that 240,000 'Rotterdam' bricks, and 60,000 big bricks 'that laid below ground'. A vault was built over the gate, and the floor above it was tiled. Two small protruding towers were added to the gate house. A stair tower was added to provide access to all the new rooms. Also 12 glass windows were made.[10]

The changes led to a situation which was almost that of the 17th and 18th century depictions of the castle.[10] The accounts show that many of the changes made the castle far more inhabitable.

The 1476-1478 changes also had to do with the ring wall. In 1822 it was estimated that the castle contained 270,000 bricks.[10] This estimate was based on the ring wall being 'three bricks' thick, i.e. 3 * 29 cm = 90 cm, and 6.12 m high.[11] Renaud did not address it, but of course the 2.5 m thick wall at the foundation level is at odds with this 90 cm thick wall of 1822. The answer might be in the account referring to ende om den rinck van den huyse up den muur een cardeelinge te maken (and on the ring of the house to create a cardeelinge on the wall.[11] Renaud was not sure about the meaning of the word cardeelinge,[10] but it could refer to the 90 cm thick wall being built on top of the thicker wall.

Phase 3

On depictions, Windenburg is often shown with a protruding square room. This is attributed to a 17th-century change.[9] In 1695 Hildernisse came by and made a floor plan of the main floor of the castle, i.e. above the basement floor plan that was made in the 1950s. Hildernisse's floor plan survived only in copy. Therefore, we're not sure whether the details are from him or the copyist.[12]

Like all (copies of) Hildernisse's work, it depicts an irregular situation as if it was totally regular. E.g. the location of the gatehouse, which Renaud noted to be incorrect. However, at the time he wrote about Windenburg, Renaud was obviously not aware of this trait of Hildernisse's work. Renaud therefore thought that the internal walls that Hildernisse depicted at other locations had been built on their own foundations and that these foundations had disappeared before the 1950s.[9] For Hildernisse's eastern internal wall, Renaud indeed doubted Hildernisse, and assumed that it was built on top of the original eastern internal wall found on the foundations.[9]

In 1776 an inventory was made, listing the rooms on the main floor of the castle.[11]

History

The Lordship Dreischor

The heerlijkheid (lordship) Dreischor was older than Windenburg. It used to belong to Klaes van Cats. Wiliam III of Holland (reign 1304–1337) granted it to John of Beaumont (1288-1356) at an unknown date. At his death Dreischor was inherited by Louis III, Count of Blois, son of his daughter. Of this time, between 1356 and 1371 a complete set of accounts about Dreischor survives, but it does not mention a castle.[9] In summary, it is very unlikely that the counts of Blois founded Windenburg.[13]

Part of the count's domain

In 1397 Dreischor reverted to the Count Albert of Holland (1336-1404). It is thought most likely that the castle was founded shortly after. In 1411 Albert's successor William VI appointed Floris van Haamstede as burgrave while Jan van Zevenaar became bailiff and land agent. The accounts that could have told much more about Windenburg at this time were lost in the early days of World War II.[13]

Van Kleef

In 1413 Dreischor was granted to Catharina of Kleef. In 1433 Adolph I, Duke of Cleves (1373-1448) got Dreischor. In 1476-1478 the land agent Beooster Schelde managed a large renovation of Windenburg, see above. After his successor Philip of Cleves, Lord of Ravenstein died in 1528, Dreischor again reverted to the count.[14]

The emperor's house

After 1528, Windenburg (which had never been called that) got the name s Keijzershuis, meaning: 'the emperor's house'.[15] After Philip II of Spain was deposed, Windenburg came to the Provincial Council of Zeeland

Residence of Regents

It seems that Windenburg was only granted again, or rather sold, at a public auction 1705. For 12,300 guilders mr. Jan Daniëlsz. Ockerse (1668-1742) twice mayor of Zierikzee, became the new owner. He is buried in the church of Dreischor. Jan was succeeded by his nephew mr. Pieter Mogge (1698-1756).[16]

In 1753 Dreischor and Windenburg were bought by mr. Andries Heshuysen (1721-1776) pensionary of Zierkikzee. Andries and his predecessors did not use Windenburg extensively, and were probably only there in the Summer.[16]

An absentee Lord

In 1776 Andries' nephew Cornelis de Jonge inherited Windenburg and 78,000 guilders. It's not known whether the castle was still inhabited in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, because De Jonge lived in Kleef.[16]

In 1822 De Jonge asked the architect of Zierikzee to compute the revenues of breaking up Windenburg. These were estimated at 1,785 guilders.[16]

Demolishement

Breakup

.JPG.webp)

In 1837 De Jonge in effect ordered the sale of the castle for break up. It meant that the building was sold, but not the ground. Buyer was Barend Janse carpenter from Brouwershaven for 3,475 guilders. The gate now stands at the cemetery 'Onder de Linden' in Sint-Maartensdijk.[16]

In 1874 and 1875 Dreischor municipality then bought the terrain, with the castle moats.[17]

The 1953 North Sea flood

The North Sea flood of 1953 also flooded Dreischor. It left the village under a layer of sediment. Mayor A.H. Vermeulen asked the clean up crew to also clear the foundations of Windenburg. These were then put on a map by the Centrale Dienst Noord-Zeeland.[17]

First a plan was made to build houses on the plot. Next there were thoughts about a medical center, but in the end the municipality opted to build a residence for the mayor. The idea was that building a great house at the entrance of the village would enhance its stature. On 18 May 1955 the municipality ordered the construction, which was approved by the province on 26 July.[17]

Meanwhile, Mr. Glazema of the Rijksdienst voor Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek (National Archaeology Service) had visited Dreischor and filed a protest.[17] The archaeologist Jaap Renaud also arrived, and so a quick investigation was started. Now, it was discovered that by the sale in 1837, an explicit ban had been stipulated against breaking off the foundations. By August 1955 the municipality was in conflict with the archaeology service. However, two years before, the mayor had himself informed the service for the preservation of monuments without receiving any objections. It probably decided the case in his favor.[18]

In the end the national government did not revoke the provincial approval. It meant that the Archaeology service lost the case.[19]

In August 1956 the mayor of Dreischor moved to his new residence. On 1 January 1961 Dreischor municipality was disbanded. The new municipality Brouwershaven sold the building to private owners in 1968.[19]

References

- Kuipers, J.J.B. (2006), "Windenburg", Kastelenlexicon, Nederlandse Kastelen Stichting (NKS)

- Renaud, Jaap (1956), "Huis Windenburg te Dreischor", Berichten van de Rijksdienst voor het Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek, Rijksdienst voor het Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek, vol. VII, pp. 85–88

- Renaud, Jaap (1957), "Het huis Windenburg te Dreischor", Bulletin KNOB, Koninklijke Nederlandse Oudheidkundige Bond, pp. 2–19, doi:10.7480/knob.6.1957.10

- Uil, H. (1994), "Kasteel Windenburg in Dreischor", Nehalennia, Koninklijk Zeeuws Genootschap der Wetenschappen, pp. 15–19

Notes

- Uil 1994, p. 16.

- Renaud 1956, p. 88.

- Renaud 1957, p. 6.

- Renaud 1956, p. 85.

- Renaud 1957, p. 7.

- Renaud 1956, p. 86.

- Renaud 1957, p. 20.

- Renaud 1957, p. 8.

- Renaud 1957, p. 12.

- Renaud 1957, p. 11.

- Renaud 1957, p. 4.

- Renaud 1957, p. 1.

- Renaud 1957, p. 13.

- Renaud 1957, p. 14.

- Kuipers 2006, p. Bezits- en bouwgeschiedenis.

- Uil 1994, p. 17.

- Uil 1994, p. 18.

- "Historici protesteren tegen bouw van burgemeesterswoning op fundamenten van kasteel..." Trouw. 8 August 1955.

- Uil 1994, p. 19.