Women's suffrage in India

The Women's suffrage movement in India fought for Indian women's right to political enfranchisement in Colonial India under British rule. Beyond suffrage, the movement was fighting for women's right to stand for and hold office during the colonial era. In 1918, when Britain granted limited suffrage to women property holders, the law did not apply to British citizens in other parts of the Empire. Despite petitions presented by women and men to the British commissions sent to evaluate Indian voting regulations, women's demands were ignored in the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms. In 1919, impassioned pleas and reports indicating support for women to have the vote were presented by suffragists to the India Office and before the Joint Select Committee of the House of Lords and Commons, who were meeting to finalize the electoral regulation reforms of the Southborough Franchise Committee. Though they were not granted voting rights, nor the right to stand in elections, the Government of India Act 1919 allowed Provincial Councils to determine if women could vote, provided they met stringent property, income, or educational levels.

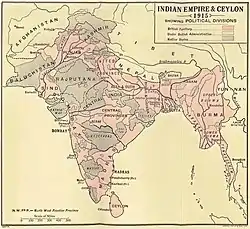

Between 1919 and 1929, all of the British Provinces, as well as most of the Princely states granted women the right to vote and in some cases, allowed them to stand in local elections. The first win was in the City of Madras in 1919, followed by the Kingdom of Travancore and the Jhalawar State in 1920, and in the British Provinces, the Madras Presidency and Bombay Presidency in 1921. The Rajkot State granted full universal suffrage in 1923 and in that year elected the first two women to serve on a Legislative Council in India. In 1924, the Muddiman Committee conducted a further study and recommended that the British Parliament allow women to stand in elections, which generated a reform on voting rights in 1926. In 1927, the Simon Commission was appointed to develop a new India Act. Because the commission contained no Indians, nationalists recommended boycotting their sessions. This created fractures among women's groups, who aligned on one side in favour of universal suffrage and on the other in favour of maintaining limited suffrage based on educational and economic criteria.

The Commission recommended holding Round Table Conferences to discuss extending the franchise. With limited input from women, the report from the three Round Tables was sent to the Joint Committee of the British Parliament recommending lowering the voting age to 21, but retaining property and literacy restrictions, as well as basing women's eligibility on their marital status. It also provided special quotas for women and ethnic groups in provincial legislatures. These provisions were incorporated into the Government of India Act 1935. Though it extended electoral eligibility, the Act still allowed only 2.5% of the women in India to vote. All further action to expand suffrage was tied to the nationalist movement, which considered independence a higher priority than women's issues. In 1946, when the Constituent Assembly of India was elected, 15 seats went to women. They helped draft the new constitution and in April 1947 the Assembly agreed to the principal of universal suffrage. Provisions for elections were adopted in July, India gained its independence from Britain in August, and voting rolls began being prepared in early 1948. The final provisions for franchise and elections were incorporated into the draft constitution in June 1949 and became effective on 26 January 1950, the enforcement date of the Constitution of India.

Background

In the 1890s nationalism arose in India with the founding of the Indian National Congress.[1] The advent of World War I and the use in propaganda rhetoric of terms like 'self-determination' gave rise for hope among middle-class Indians that change was imminent.[2] For English-educated elites, who had predominantly become urbanised and depended on professional income, British rule was beneficial,[3] but they also recognised that restrictions on their wives impacted their own careers. The practice of secluding women meant that they were unable to educate children or serve as hostesses or helpmeets to further their husbands' advancement.[4]

Indian women, who had begun participating in reform activities since the 19th century, also saw the potential for change. They escalated their efforts into demands for political rights and specifically for suffrage. Entwined with Indian nationalists, Indian feminists sought support from British suffragists as well as their own autonomy,[5] which prevented the development of a unified identity or set of demands from women.[6] Austen Chamberlain, the Secretary of State for India was against loosening the power of Britain in India and accused those who backed even moderate proposals for consultation of Indian princes as "meddlers" in the affairs of the British Raj.[7] When he was ousted in 1917, his replacement, Edwin Montagu, gained approval to organise with Lord Chelmsford, Viceroy of India, a consultation for a limited political devolution of British power.[8][9]

Beginning of the movement (1917–1919)

In 1917, Margaret Cousins founded the Women's Indian Association in Adyar, Madras, to create a vehicle for women to influence government policy. The organisation focused on equal rights, educational opportunity, social reform, and women's suffrage. Founding members included S. Ambujammal, Annie Besant, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, Mary Poonen Lukose, Begam Hasrat Mohani, Saralabai Naik, Dhanvanthi Rama Rau, Muthulakshmi Reddy, Mangalammal Sadasivier, and Herabai Tata. Besant was named president and Tata, general secretary.[10] Wanting to secure an audience with Montagu, Cousins sent an application requesting discussion of educational and social reforms for women. When it was rejected on the grounds that the commission's research was limited to political topics, she revised her application, focusing on the presentation of political demands of women.[11]

When it was approved, on 15 December 1917,[9] Sarojini Naidu led a deputation of 14 leading women from throughout India to present the demand to include women's suffrage in the new Franchise Bill under development by the Government of India.[10][12][13] Besides Naidu and Cousins, members of the delegation included Besant, Parvati Ammal, Mrs. Guruswamy Chetty, Nalinibai Dalvi, Dorothy Jinarajadasa, Dr. Nagutai Joshi (later known as Rani Lakshmibai Rajwade, Srimati Kamalabai Kibe, Mrs. Z. Lazarus, Mohani, Srimati S. Naik, Srimati Srirangamma, and Tata. In addition to the women physically present, telegrams of support were sent to Montagu by Francesca Arundale, Abala Bose, Sarala Devi Chaudhurani, Mrs. Mazur-al-Haque, Uma Nehru, Mrs. R. V. Nilakanta, Miss H. Petit, Ramabai Ranade, and Shrimati Padmabai Sanjiva Rao.[13]

The British Parliament passed the Representation of the People Act 1918, enfranchising women over the age of 30, who were entitled to be, or who were married to someone entitled to be, a local government elector.[14] The law did not apply to British citizens in other parts of the Empire.[15] When the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms were introduced in 1918 no recommendation was made for Indian women's enfranchisement.[16] Suffragists were active in drawing up petitions[17] and published updates about the struggle in Stri Dharma, urging support for women's political empowerment as a part of the anti-colonial movement against Britain.[18] Stri Dharma was edited by Reddy and Srimati Malati Patwardhan and aimed to develop both local and international support for women's equality.[5] Widely attended protest meetings were held throughout the country, organised by the Women's Indian Association.[19] In 1918, the provincial legislatures in Bombay and Madras passed resolutions supporting the elimination the sex disqualification for voting,[17] and women gained the endorsement for suffrage from the Indian Home Rule League and the All-India Muslim League.[20] When the Indian National Congress convened in December, Chaudhurani presented a resolution to the Congress to grant suffrage, which was taken under advisement pending the outcome of consultations with the remaining provincial legislatures.[21] Though a resolution did not pass in 1918 in Bombay, support for suffrage was approved in Calcutta.[20]

The Southborough Franchise Committee was tasked with developing the electoral regulations under the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms.[22] Though they accepted petitions from throughout India, they spoke only with women in Bengal and Punjab.[23] The Southborough Report published in April 1919 acknowledged that educated women might be qualified, but concluded that overall women were not ready for the vote, nor would conservative sectors of society support their enfranchisement.[23][24] In July women in Bombay organised a protest meeting and when Lord Southborough sent his report to the Joint Select Committee of the House of Lords and Commons the Bombay Committee on Women's Suffrage sent Tata and her daughter Mithan to give evidence along with Sir Sankaran Nair.[12][23][25]

In August 1919, Besant and Naidu presented pleas for enfranchisement to the Joint Select Committee.[26] Besant even used the argument that if Indian women were not given the vote, they might support the anti-colonial movement.[27] The following month, Tata presented the memorandum Why Should Women Have Votes to the India Office.[28] While in England, the Tatas and other suffragists spoke at various public meetings and events of British suffragists,[25] travelling to "Birkenhead, Bolton, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Harrowgate, Liverpool, Manchester and Newcastle" to gain the support of other women. They were very successful in their pleas, causing the India Office to be inundated with resolutions of support for women's suffrage in India.[29] Tata and her daughter participated in a second presentation before the Joint Select Committee on 13 October[12] and were present for the final reading of the Government of India Act in December 1919.[30]

The Act did not grant women suffrage, but included a clause that Indian provinces could enfranchise women if they chose to do so.[30] It limited suffrage, barring most of India's middle class, as it restricted the vote to those who had an annual income of more than ₹10,000–20,000; land revenues in excess of ₹250–500 per annum; or those recognised for their high level of public work or scholarship.[31] Furthermore, it did not allow women to stand in elections. The law empowered the Imperial Legislative Assembly and the Council of State to grant the right to vote in those provinces in which legislative franchise had been approved, but the British Parliament retained the right to determine who could stand as candidates for the Legislative Councils.[32]

Provincial progress (1919–1929)

Suffragists recognised that their political aims were tied to those of the Nationalist Movement. By combining their goals, both nationalists and feminists benefited by articulating their common issues, resulting in more supporters to help with resolving their challenges.[33] By linking gender equality with the removal of colonial restrictions, women were able to defuse opposition,[34] but not eliminate it entirely. For example, Mahatma Gandhi encouraged women's participation in socio-economic and political struggles,[31] but he published an article in Young India stating he did not support the campaign for women's suffrage.[35] Members of the 45 branches of the Women's Indian Association began to agitate locally for voting rights, submitting demands to their various councils[36] and the focus shifted from India-wide agitation to the provincial level.[37]

The Madras City Council passed Municipal Act IV in 1919, which gave women the right to vote, but not the right to stand in elections.[31] Women activists including Besant, Chetty, Cousins, Jinarajadasa, Lazaras, Reddi, Rama Rau, Mangalammal Sadasiva Iyer, Rukmini Lakshmipathi, Mrs. Ramachandra Rao, Mrs. Mahadeva Shastri, Mrs. C. B. Rama Rao and Mrs. Lakshman Rao, continued pressing for the same rights as male electors.[38] In 1920, the Kingdom of Travancore and the Jhalawar State granted women's suffrage.[39] In 1921, the Madras Presidency voted to remove the restriction on standing for elections at the local level, striking the sex qualification for women.[38] The first woman to be elected to the Madras City Corporation was Mrs. M. C. Devadoss.[40] Later that year, the Bombay Legislative Council passed legislation removing sex as a disqualification for voting, though educational and property qualifications remained.[41]

In Bengal in 1921, the women's organisation, Bangiya Nari Samaj, was formed to agitate for the vote. Founded by Abala Bose, who had supported the delegation to the Montagu Inquiry, members included Kumudini Bose, R. S. Hossain, Kamini Roy, and Mrinalini Luddhi Sen.[42] Nellie Sengupta was also active in Bengal in agitating for women's rights.[43] Bangiya Nari Samaj organised large public meetings hoping to influence the educated public to support women's suffrage. They spoke in towns throughout the province and published in newspapers.[44] Though a resolution for women's suffrage was presented in September, it was defeated by a vote of 56 to 37,[45] largely on the basis of arguing that granting enfranchisement would allow prostitutes to vote.[46]

In April 1922, the Kingdom of Mysore's Legislative Council granted women's suffrage,[47] followed by approval in the province of Burma in June.[48] In 1923, four women, Hari Hadgikson, Avantikabai Gokhale, Bachubai Lotvala, and Naidu, were elected to the Bombay City Corporation.[49] That year, the United Provinces Legislative Council unanimously granted women's suffrage and[40] the Rajkot State not only granted full universal suffrage but elected two women to serve on the Council.[50] As the princely kingdoms were not bound by the restriction for women standing for election, Rajkot became the first place in India where a woman was elected to the council.[51] In 1924, the Kingdom of Cochin followed suit eliminating the sex disqualification for voting and standing in an election.[40][52] When the Muddiman Committee came to India to assess the implementation and progress made on the implementation of the Act of 1919, the wife of Deep Narayan Singh stressed to the Committee women's desire to participate in the legislature. The Committee made no change to implementation by provincial authorisation,[53] but did recommend that the bill be reformed to allow women to be elected to legislative positions. Before the end of the year, Assam Province passed a woman's suffrage resolution.[54]

The National Council of Women in India was established in 1925. It was led by Lady Meherbai Tata[55] and most of its members were among the elite classes. An affiliate of the International Council of Women, the group, which included Marahani of Baroda, Tarabai Premchand, Dowager Begum Saheb of Bhopal, and Cornelia Sorabji, strove to maintain connections with the British and focused on petition politics. [56] Mithan Lam (née Tata) joined the council and led the legislative committee, which worked to improve the status of women.[57] Women's suffrage was passed in the Bengal Presidency in 1925,[40][58] and was approved in 1926 in Punjab.[59][60] That year, the British Parliament allowed the Government of India to amend the electoral rules granting women the right to become legislative members and Madras granted the right for women to stand in elections for the Provincial Legislative Council.[61] Also in 1926, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, an active worker in registering women to vote,[62] became the first woman to stand for a legislative seat in the British provinces, but lost by a small margin.[63][64]

In 1927, the Madras Legislative Council appointed Muthulakshmi Reddy, who became the first woman legislator in the British provinces.[56][65] The All India Women's Conference (AIWC) was organised in Poona that year by Cousins, initially to deal with girls' education.[66] Recognizing improvements in education depended on a revision of social customs, the organisation worked on social and legal issues that benefited women with the aim of improving the nation.[67] Women gained enfranchisement in the Central Provinces, in 1927, and in Bihar and Orissa Province, in 1929.[40] At the end of the 1920s, franchise had been extended to almost all provinces in India. However, because of the property qualification, less than 1% of the women in the country were able to vote.[68] Though they qualified for registration under the same terms as men, the income requirements meant that only about 1 million women were able to vote or stand in elections.[6]

Extending the franchise (1930–1935)

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, tensions arose among various women's groups depending on whether or not they supported the British schemes for extending franchise. The major all-India organisations continued to demand universal suffrage, whereas British women's groups favoured proposals which maintained the social order.[6] These tensions were brought about by the appointment in 1927, of the Simon Commission, which was tasked with developing a new India Act.[69] In response, the Nehru Report, which came out of the All Parties Conference of 1928, was drafted to recommend that dominion status be given to India within the British Commonwealth. The Nehru Report recommended adoption of a bill of rights giving men and women equality.[70] The Simon Commission arrived in India in 1929 and began soliciting input. Because the leaders of the nationalist movement were against the seven white men on the commission deciding the fate of Indians, the Women's Indian Association refused to meet with commissioners, as did the All India Women's Conference.[69]

When Gandhi began the Civil Disobedience Movement in 1930, the British response was to ban the Indian National Congress and arrest its leadership.[71] Initially he was reluctant to have women participate, but its non-violent aspect appealed to women and soon thousands of women from throughout India were participating in violating the salt laws.[71] When the men were arrested, women stepped in to continue manufacturing and selling salt to defy the British monopoly and continue the movement.[72][73] Leaders included Anasuya Ben, Perin Naoroji Captain, Chattopadhyay, Gokhale, Lakshmipathi, Hansa Mehta, Sharda Mehta, Naidu, and Saraladevi Sarabhai, among others.[74][73] Proving their leadership abilities,[71] the women held daily councils to plan the day-to-day activities,[72] including protesting at liquor and shops that dealt in imported cloth.[75] For example, they scheduled shifts of four women a day twice a day for two hours, to picket at each of the 500 liquor shops in Bombay.[76] Many women were assaulted and arrested for their participation in civil disobedience protests.[77]

When the Round Table Conference was scheduled in London for 1930, initially the Women's Indian Association reversed their boycott,[69] submitting a memorandum which stressed how women's co-operation had been shown to be valuable in resolving political problems.[78] They withdrew from participation again when the commission declaration stated the meeting was to "discuss" rather than "implement" further change. Those chosen to participate with the commission included Begum Jahan Ara Shah Nawaz and Radhabai Subbarayan, though the British appointed them without consulting any women's organisations. They agreed to accept interim measures expanding suffrage to literate women and granting special reservations[69] of four legislative seats to encourage women's input on education and social issues.[70]

Cousins and Reddy of the Women's Indian Association, Shareefa Hamid Ali and Rajwade from the All India Women's Conference, and Premchand from the National Council of Women in India jointly prepared a memorandum supporting universal suffrage with no special reservations.[79] This was a compromise position, as initially the women saw the benefit of having seats reserved to ensure women's representation. Under pressure from nationalist leaders, these women's organisations acquiesced to the nationalists, thereafter supporting no preferential treatment for any group.[80] A delegation of women, led by Rani Lalit Kumari (Dowager Rani of Mandi), and including Mrs. Ahmad, a former council member from the United Provinces Legislature and Satyavati Singh Chitambar,[81] president of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union of India,[82] recommended that women be enfranchised based upon marriage. They also proposed that the property requirement for women should be twice that for men.[81] The recommendations originating from the committee included being a wife or widow, having attained the age of 25 and whose spouse met (or had met before death) the property requirements of 1919.[83]

When the Gandhi-Irwin Pact of 1931 was signed, and the Indian National Congress agreed to participate in the round table process, women supporting the nationalist aims agreed to participate as well.[79] At the Second Round Table Conference held that year, suffragists of the Women's Indian Association, National Council of Women of India, and the All-Indian Women's Conference submitted a joint memorandum demanding full adult franchise. They rejected sex disqualification for candidacy, employment, holding public office, or voting, as well as special provisions to make places for women in the legislature. The memorandum was presented by Naidu, but Subbarayan countered with a recommendation for 5% of the legislative seats over the next three election cycles to be reserved for women.[84] As there was no agreement among the Indian delegates, the Second Round Table recommended that each provincial legislature have seats allocated for specific communities and 2.5% of the overall seats be reserved for women. The three major suffragist groups were disappointed and sent a telegram to the Viceroy expressing their frustration with communal organisation of seats.[85]

The Third Round Table meeting took place in 1932 and the only woman present was Nawaz. Though she supported limited suffrage,[85] when a White Paper was developed for a Joint Select Committee of Parliament, she urged Amrit Kaur and Reddy to prepare a case and select a delegate to testify before the committee. Ali, Kaur and Reddy were chosen as delegates to present a second memorandum. Throughout the summer of 1933, the women, including Nawaz, toured Britain and tried to gain support from British suffragists for Indian women's voting rights.[86] In October 1934, the Joint Committee published their report, which was incorporated into the Government of India Act 1935. Eligibility for women voters was revised under the act to include women aged 21 or over who met the same property qualifications as men, who were literate in any language in use in India, and who were wives or widows of a person who had paid income tax in the prior financial year or had served in the Royal Military. It also reserved seats for women in the lower house and excluded them from the second chamber entirely.[87] Once again women from the Women's Indian Association, National Council of Women of India, and the All-Indian Women's Conference issued a joint statement of their dissatisfaction with voting being tied to marital status, income and property requirements that excluded the majority from voting, and special privileges that treated men and women differently.[88]

Push for independence (1935–1947)

The Government of India Act 1935 extended the vote to include around 6 million women, but even so covered only 2.5% of the women in India.[89] "In the 1937 elections, 10 women were elected from general constituencies, 41 from reserved constituencies, and five were nominated to provincial legislative councils".[90] The struggle to further expand the franchise was tied to the drive to gain independence,[91] though independence took priority over women's issues.[92] In 1938, the Indian National Congress set up a subcommittee, which included Ali, Chaudhurani, Kaur, Naidu, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, Rajwade, Mridula Sarabhai, and Jahanara Shahnawaz. They were tasked with defining the role of women in society.[93] Working with members of the Women's Indian Association and the All India Women's Conference, they focused on a society reordered so that men and women were equal partners, demanding equal status and opportunity with full political rights. They also recommended schemes to develop child care, health, and social insurance services; a uniform civil code which protected the economic rights of women and provided protection for children's rights, equal rights to marriage and divorce, guardianship, and nationality; and uniform educational standards regardless of gender.[93][94] Similarly, that same year the All-India Muslim League established a sub-committee for women and encouraged their participation in fundraising, mass processions and public meetings. They also were actively involved in campaigning for women to participate as voters.[95]

The nationalist movement allowed women to enter the public sphere, but did not generally transform the inequality of their lives.[96] Though they were able to press for the passage of the Sarda Act of 1929, which raised the age of marriage, members of the Women's Indian Association and the All India Women's Conference were often rebuffed by the nationalist leaders in their attempts to legalise equality.[97] When the Constituent Assembly of India was elected in 1946, 15 women gained seats.[98] They included Purnima Banerjee, a member of the All India Women's Conference;[99] Kamla Chaudhry, a feminist writer and independence activist;[100] Malati Choudhury, an activist in the nationalist movement;[101] Durgabai Deshmukh, an independence activist, lawyer, social worker, and women's rights activist;[102] Kaur, co-founder of the All India Women's Conference;[103] Sucheta Kriplani, a nationalist activist and member of the women's committee of the Indian National Congress;[104] Annie Mascarene, a lawyer and activist from the independence movement;[105] Hansa Mehta, president of the All India Women's Conference;[106] Naidu, a member of the Women's Indian Association;[107] Pandit, a member of the All India Women's Conference;[108] Begum Aizaz Rasul, a member of the All India Women's Conference;[109] Renuka Ray, a member of the All India Women's Conference;[110] Leela Roy, a founder of the militant women's political organisation Congress Mahila Sangha, in Bengal;[111] Ammu Swaminathan, a member of the Women's Indian Association;[112] and Dakshayani Velayudhan, a teacher and delegate in the Cochin Legislative Assembly.[113]

These women helped draft the Constitution of India and worked to ensure that socio-economic and political inequalities were addressed.[114] One of the first actions of the Assembly was to establish universal adult suffrage, eliminating the gender, income, property, and educational restrictions on voting.[115] In April 1947, the Advisory Committee on the Subject of Fundamental Rights reported that both the Fundamental Rights Sub-Committee and the Minorities Sub-Committee agreed to the principal. The Constituent Assembly adopted provisions for elections on this basis in July.[116] The Assembly also passed legally enforceable statutes to protect fundamental rights, such as guaranteeing equality and equal opportunity for men and women; eliminating discrimination on the basis of caste, race religion, or sex by either the government or an employer; and banning untouchability; among other provisions.[115]

With the passage of the Indian Independence Act 1947 by the British parliament, the Constitutional Assembly became the parliament of the Dominion of India on 15 August.[117] In November, the Secretariat of the Constituent Assembly sent out a memorandum regarding general elections to be held under universal adult suffrage and in March 1948, general instructions for preparation of electoral roles were issued to all the Provincial and State governments. The instructions advised anyone who was a resident, of sound mind, and not a criminal of the age of at least 21 was entitled to be registered.[118] The goal was to have complete rolls drafted so that immediately after the Constitution was adopted elections for the new government could be held.[119] Despite agreeing upon the principal of universal adult suffrage upon starting the constitutional debates, "the key provisions for franchise and elections were only debated and passed in June 1949".[116] The provisions officially replaced those contained in the Government of India Act of 1935, thereafter being adopted by the Constituent Assembly in November 1949 for the formal enforcement date of 26 January 1950.[120]

See also

- Domestic violence in India

- Dowry system in India

- Female foeticide in India

- Gender inequality in India

- Gender pay gap in India

- Men's rights movement in India

- National Commission for Women

- Rape in India

- Welfare schemes for women in India

- Women in India

- Women in Indian Armed Forces

- Women's Reservation Bill

References

Citations

- Copland 2002, p. 27.

- Copland 2002, p. 34.

- Southard 1993, pp. 399–400.

- Southard 1993, p. 400.

- Burton 2016.

- Fletcher, Levine & Mayhall 2012, p. 225.

- Copland 2002, pp. 35–36.

- Copland 2002, p. 37.

- Forbes 2004, p. 92.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 179.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 180.

- Mukherjee 2011, p. 112.

- Deivanai 2003, p. 113.

- Smith 2014, p. 90.

- Fletcher, Levine & Mayhall 2012, p. xiii.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 182.

- Forbes 2004, p. 93.

- Tusan 2003, p. 624.

- Deivanai 2003, p. 116.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 183.

- Forbes 2004, p. 94.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 184.

- Forbes 2004, p. 95.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 185.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 186.

- Forbes 2004, p. 97.

- Deivanai 2003, p. 119.

- Mukherjee 2018a, p. 81.

- Mukherjee 2018a, pp. 82–83.

- Mukherjee 2018b.

- Deivanai 2003, p. 121.

- Bennett 1922, p. 536.

- Deivanai 2003, pp. 121–123.

- Deivanai 2003, p. 124.

- Forbes 2004, p. 100.

- Deivanai 2003, pp. 125–126.

- Southard 1993, pp. 404–405.

- Deivanai 2003, pp. 128–129.

- Bennett 1922, p. 535.

- Deivanai 2003, p. 129.

- Odeyar 1989, pp. 186–187.

- Southard 1993, pp. 405–407.

- Southard 1993, p. 415.

- Southard 1993, pp. 407–408.

- Southard 1993, p. 409.

- Southard 1993, p. 414.

- Bennett 1924, p. 410.

- The Woman's Leader 1922, p. 153.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 191.

- International Woman Suffrage News 1923, p. 156.

- Bennett 1924, p. 411.

- Bennett 1924, pp. 410–411.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 192.

- Bennett & Low 1936, pp. 621–622.

- Forbes 2004, p. 75.

- Desai & Thakkar 2001, p. 5.

- Forbes 2004, p. 76.

- Southard 1993, p. 398.

- Forbes 2004, p. 101.

- Pearson 2006, p. 430.

- Deivanai 2003, p. 131.

- Deivanai 2003, pp. 131–132.

- Jain 2003, p. 108.

- Brijbhushan 1976, pp. 30–31.

- Bennett & Low 1936, p. 622.

- Forbes 2004, pp. 78–79.

- Forbes 2004, pp. 80–81.

- Fletcher, Levine & Mayhall 2012, p. 194.

- Forbes 2004, p. 106.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 195.

- Deivanai 2003, p. 134.

- Deivanai 2003, p. 137.

- Forbes 2004, p. 132.

- Deivanai 2003, p. 136.

- Deivanai 2003, p. 135.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 242.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 248.

- Deivanai 2003, p. 141.

- Forbes 2004, p. 107.

- Keating 2011, p. 55.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 196.

- The Christian Advocate 1936, p. 85.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 197.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 198.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 199.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 200.

- Odeyar 1989, pp. 201–202.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 202.

- Odeyar 1989, pp. 202–203.

- Desai & Thakkar 2001, p. 8.

- Odeyar 1989, p. 203.

- Desai & Thakkar 2001, p. 9.

- Desai & Thakkar 2001, p. 10.

- Keating 2011, p. 51.

- Lambert-Hurley 2005, p. 61.

- Desai & Thakkar 2001, p. 13.

- Keating 2011, p. 49.

- Srivastava 2018.

- Ansari & Gould 2019, p. 201.

- Tharu & Lalita 1991, p. 47.

- Joshi 1997, p. 83.

- Deshpande 2008, p. 42.

- Bhardwaj 2019.

- Jain 2003, p. 203.

- Ravichandran 2018.

- Sluga 2013, p. 186.

- Pasricha 2009, p. 24.

- Hardgrove 2008.

- Hansa 1937, p. 90.

- Robinson 2017, p. 182.

- Kumari 2009, p. 259.

- Mathew 2018.

- Kshīrasāgara 1994, p. 362.

- Desai & Thakkar 2001, pp. 14–15.

- Keating 2011, p. 65.

- Shani 2018, p. 161.

- Thiruvengadam 2017, p. 40.

- Shani 2018, p. 91.

- Shani 2018, p. 99.

- Thiruvengadam 2017, p. 43.

Bibliography

- Ansari, Sarah; Gould, William (2019). Boundaries of Belonging: Localities, Citizenship and Rights in India and Pakistan. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-19605-6.

- Bennett, Stanley Reed, ed. (1922). "The Woman Suffrage Movement". The Indian Year Book. London: Coleman & Co., Ltd. pp. 533–536. OCLC 4347383.

- Bennett, Stanley Reed, ed. (1924). "The Woman Suffrage Movement". The Indian Year Book. London: Coleman & Co., Ltd. pp. 409–411. OCLC 4347383.

- Bennett, Stanley Reed; Low, Francis, eds. (1936). "The Woman Suffrage Movement". The Indian Year Book. London: Coleman & Co., Ltd. pp. 620–622. OCLC 4347383.

- Bhardwaj, Deeksha (2 February 2019). "Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, the Princess Who Was Gandhi's Secretary & India's First Health Minister". The Print. New Delhi, India. Archived from the original on 18 October 2019.

- Brijbhushan, Jamila (1976). Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya: Portrait of a Rebel. New Delhi, India: Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-033-4.

- Burton, Antoinette (3 August 2016). "Race, Empire, and the Making of Western Feminism". Routledge Historical Resources. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781138641839-HOF7-1 (inactive 1 August 2023). Retrieved 24 November 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - Copland, Ian (2002). The Princes of India in the Endgame of Empire, 1917–1947. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89436-4.

- Deivanai, P. (May 2003). Feminist Struggle for Universal Suffrage in India with Special Reference to Tamilnadu 1917 to 1952 (PhD). Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu: Bharathiar University. hdl:10603/101938.

- Desai, Neera; Thakkar, Usha (2001). Women in Indian Society (1st: 2004 reprint ed.). New Delhi, India: National Book Trust. ISBN 81-237-3677-0.

- Deshpande, Prachi (2008). "Deshmukh Durgabai (1909-1981)". In Smith, Bonnie G. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Vol. 1: Abayomi-Czech Republic. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-19-514890-9.

- Fletcher, Ian Christopher; Levine, Philippa; Mayhall, Laura E. Nym, eds. (2012). Women's Suffrage in the British Empire: Citizenship, Nation and Race. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-63999-0.

- Forbes, Geraldine Hancock (2004). Women in Modern India. The New Cambridge History of India. Vol. 4 (Reprint ed.). New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65377-0.

- Hansa, Mehta Shrimati (1937). All-India Women's Conference: 12th Session, Nagpur, 28 to 31 December 1937 (Report). India: All-India Women's Conference.

- Hardgrove, Anne (2008). "Pandit, Vijayalakshmi (1900–1990)". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-33786-0. Retrieved 27 November 2019. – via Oxford University Press's Reference Online (subscription required)

- Jain, Simmi (2003). Encyclopaedia of Indian Women Through the Ages. Vol. III: Period of Freedom Struggle. Delhi, India: Kalpaz Publications. ISBN 978-81-7835-174-2.

- Joshi, Naveen (1997). "Malati Choudhury: A Different Dusk". Freedom Fighters Remember. New Delhi, India: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting of the Government of India. pp. 83–86. ISBN 978-81-230-0575-1.

- Keating, Christine (2011). Decolonizing Democracy: Transforming the Social Contract in India. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-04863-5. – via Project MUSE (subscription required)

- Kshīrasāgara, Rāmacandra K. (1994). "Velayudhan Dakshayani (1912-1978)". Dalit Movement in India and Its Leaders, 1857-1956. New Delhi, India: M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 362–363. ISBN 978-81-85880-43-3.

- Kumari, Nirmala (2009). Womens Participation in Freedom Movement of India from 1920 to 1947 (PhD). Rohtak, India: Maharshi Dayanand University. hdl:10603/114717.

- Lambert-Hurley, Siobahn (2005). "Colonialism and Imperialism: British Colonial Domains of South Asia". In Joseph, Suad (ed.). Encyclopedia of Women and Islamic Cultures: Family, Law and Politics. Vol. 2: Family, Law, and Politics. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Publishers. pp. 59–61. ISBN 90-04-12818-2.

- Mathew, Soumya (3 February 2018). "Ammu Swaminathan: The Strongest Advocate against Caste Discrimination, She Lived by Example". The Indian Express. Mumbai, India. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Mukherjee, Sumita (2018a). Indian Suffragettes: Female Identities and Transnational Networks. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press India. ISBN 978-0-19-909370-0.

- Mukherjee, Sumita (2011). "Herabai Tata and Sophia Duleep Singh: Suffragette Resistances for Indian and Britain, 1910-1920". In Mukherjee, Sumita; Ahmed, Rehana (eds.). South Asian Resistances in Britain, 1858 - 1947. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 106–121. ISBN 978-1-4411-5514-6.

- Mukherjee, Sumita (15 February 2018b). "Tata [married name Lam], Mithan Ardeshir [Mithibai] (1898–1981)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.013.111939. Retrieved 22 November 2019. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Odeyar, S. B. (1989). The Role of Marathi Women in the Struggle for India's Freedom (PhD). Kolhapur, Maharashtra: Shivaji University. hdl:10603/140691.

- Pasricha, Ashu (2009). The Political Thought of Annie Besant. Encyclopaedia of Eminent Thinkers. Vol. 25. New Delhi, India: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-8069-585-8.

- Pearson, Gail (2006). "9. Tradition, Law and the Female Suffrage Movement in India". In Edwards, Louise; Roces, Mina (eds.). Women's Suffrage in Asia: Gender, Nationalism and Democracy. London, England: Routledge. pp. 408–456. ISBN 978-1-134-32035-6.

- Ravichandran, Priya (16 February 2018). "Annie Mascarene: Freedom Fighter, Nation Builder, Guardian of Democracy and Kerala's First MP". The Indian Express. Mumbai, India. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Robinson, Catherine A. (2017). Tradition and Liberation: The Hindu Tradition in the Indian Women's Movement. New York, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-82200-1.

- Shani, Ornit (2018). How India Became Democratic: Citizenship and the Making of the Universal Franchise. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-06803-2.

- Sluga, Glenda (2013). Internationalism in the Age of Nationalism. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0778-1.

- Smith, Harold L. (2014). The British Women's Suffrage Campaign 1866-1928 (Revised 2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-86225-3.

- Southard, Barbara (1993). "Colonial Politics and Women's Rights: Woman Suffrage Campaigns in Bengal, British India in the 1920s" (PDF). Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. 27 (2): 397–439. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00011549. ISSN 0026-749X. S2CID 145276788. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Srivastava, Yoshita (26 January 2018). "These Are the 15 Women Who Helped Draft the Indian Constitution". Feminism in India. New Delhi, India: FII Media. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Tharu, Susie J.; Lalita, Ke (1991). Women Writing in India: 600 B.C. to the Early Twentieth Century. New York City, New York: Feminist Press. ISBN 978-1-55861-027-9.

- Thiruvengadam, Arun K. (2017). The Constitution of India: A Contextual Analysis. New Delhi, India: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84946-869-5.

- Tusan, Michelle Elizabeth (2003). "Writing Stri Dharma: International Feminism, Nationalist Politics, and Women's Press Advocacy in Late Colonial India". Women's History Review. Milton Park, Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis. 12 (4): 623–649. doi:10.1080/09612020300200377. ISSN 0961-2025. S2CID 219611926.

- "Popular Government in Rajkot: Universal Franchise". International Woman Suffrage News. London: International Woman Suffrage Alliance. 17 (9): 156. July 1923. OCLC 41224540. Retrieved 26 November 2019 – via LSE Digital library.

- "The Methodist Woman" (PDF). The Christian Advocate. New York City, New York. 23 January 1936. p. 85. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019 – via The General Commission on Archives and History of the United Methodist Church. Clipping contained on page 2 of a PDF file of clippings on Satyavati Singh Chitambar and her husband Bishop Jashwant Chitambar.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Women Suffrage in Burma". The Woman's Leader. London: Common Cause Publishing Co., Ltd. XIV (20): 153. 16 June 1922. OCLC 5796207. Retrieved 26 November 2019 – via LSE Digital library.