Oxalis

Oxalis (/ˈɒksəlɪs/ (American English)[1] or /ɒksˈɑːlɪs/ (British English))[2] is a large genus of flowering plants in the wood-sorrel family Oxalidaceae, comprising over 550 species.[3] The genus occurs throughout most of the world, except for the polar areas; species diversity is particularly rich in tropical Brazil, Mexico, and South Africa.

| Oxalis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Oxalis pes-caprae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Oxalidales |

| Family: | Oxalidaceae |

| Genus: | Oxalis L. |

| Species | |

|

About 550, see List of Oxalis species | |

Many of the species are known as wood sorrels (sometimes written "woodsorrels" or "wood-sorrels") as they have an acidic taste reminiscent of the sorrel proper (Rumex acetosa), which is only distantly related. Some species are called yellow sorrels or pink sorrels after the color of their flowers instead. Other species are colloquially known as false shamrocks, and some called sourgrasses. For the genus as a whole, the term oxalises is also used.

Description and ecology

These plants are annual or perennial. The leaves are divided into three to ten or more obovate and top-notched leaflets, arranged palmately with all the leaflets of roughly equal size. The majority of species have three leaflets; in these species, the leaves are superficially similar to those of some clovers.[4] Some species exhibit rapid changes in leaf angle in response to temporarily high light intensity to decrease photoinhibition.[5]

The flowers have five petals, which are usually fused at the base, and ten stamens. The petal color varies from white to pink, red or yellow;[6] anthocyanins and xanthophylls may be present or absent but are generally not both present together in significant quantities, meaning that few wood-sorrels have bright orange flowers. The fruit is a small capsule containing several seeds. The roots are often tuberous and succulent, and several species also reproduce vegetatively by production of bulbils, which detach to produce new plants.

Several Oxalis species dominate the plant life in local woodland ecosystems, be it Coast Range ecoregion of the North American Pacific Northwest, or the Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest in southeastern Australia where least yellow sorrel (O. exilis) is common. In the United Kingdom and neighboring Europe, common wood sorrel (O. acetosella) is the typical woodland member of this genus, forming large swaths in the typical mixed deciduous forests dominated by downy birch (Betula pubescens) and sessile oak (Quercus petraea), by sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus), common bracken (Pteridium aquilinum), pedunculate oak (Q. robur) and blackberries (Rubus fruticosus agg.), or by common ash (Fraxinus excelsior), dog's mercury (Mercurialis perennis) and European rowan (Sorbus aucuparia); it is also common in woods of common juniper (Juniperus communis ssp. communis). Some species – notably Bermuda-buttercup (O. pes-caprae) and creeping woodsorrel (O. corniculata) – are pernicious, invasive weeds when escaping from cultivation outside their native ranges; the ability of most wood-sorrels to store reserve energy in their tubers makes them quite resistant to most weed control techniques.

A 2019 study[7] suggested that species from this genus have a symbiotic relationship with nitrogen fixing Bacillus endophytes, storing them in plant tissues and seeds, which could explain its ability to spread rapidly even in poor soils.

Tuberous woodsorrels provide food for certain small herbivores – such as the Montezuma quail (Cyrtonyx montezumae). The foliage is eaten by some Lepidoptera, such as the Polyommatini pale grass blue (Pseudozizeeria maha) – which feeds on creeping wood sorrel and others – and dark grass blue (Zizeeria lysimon).

Oxalis species are susceptible to rust (Puccinia oxalidis).

Use by humans

As food

Wood sorrel (a type of oxalis) is an edible wild plant that has been consumed by humans around the world for millennia.[8] In Dr. James Duke's Handbook of Edible Weeds, he notes that the Native American Kiowa people chewed wood sorrel to alleviate thirst on long trips, the Potawatomi cooked it with sugar to make a dessert, the Algonquin considered it an aphrodisiac, the Cherokee ate wood sorrel to alleviate mouth sores and a sore throat, and the Iroquois ate wood sorrel to help with cramps, fever and nausea.[8]

The fleshy, juicy edible tubers of the oca (O. tuberosa) have long been cultivated for food in Colombia and elsewhere in the northern Andes mountains of South America. It is grown and sold in New Zealand as "New Zealand yam" (although not a true yam), and varieties are now available in yellow, orange, apricot, and pink, as well as the traditional red-orange.[9]

The leaves of scurvy-grass sorrel (O. enneaphylla) were eaten by sailors travelling around Patagonia as a source of vitamin C to avoid scurvy.

In India, creeping wood sorrel (O. corniculata) is eaten only seasonally, starting in December–January. The Bodos of north east India sometimes prepare a sour fish curry with its leaves. The leaves of common wood sorrel (O. acetosella) may be used to make a lemony-tasting tea when dried.

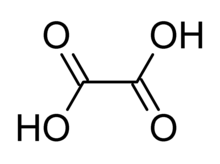

For its oxalic acid content

.jpg.webp)

A characteristic of members of this genus is that they contain oxalic acid (whose name references the genus), giving the leaves and flowers a sour taste which can make them refreshing to chew.[10] The crude calcium oxalate ranges from 13 to 25 mg/g fresh weight for woodsorrel as compared to 1.3 to 1.8 mg/g for spinach.[11] In very large amounts, oxalic acid may be considered slightly toxic, interfering with proper digestion and kidney function. However, oxalic acid is also present in more commonly consumed foods such as spinach, broccoli, brussels sprouts, grapefruit, chives, and rhubarb, among many others.[12] A non-medical expert summary is that, on the one hand, the risk of actual poisoning from oxalic acid in persons with normal kidney function is "wildly unlikely." On the other hand, the mechanical effects of crystals of calcium oxalate contribute substantially to some pathological conditions, such as gout and (especially) nephrolithiasis.[13]

While any oxalic acid-containing plant, such as Oxalis, is toxic to humans in some dosage,[14] the U.S. National Institutes of Health note that oxalic acid is present in many foodstuffs found in the supermarket and its toxicity is generally of little or no consequence for people who eat a variety of foods.[15]

In the past, it was a practice to extract crystals of calcium oxalate for use in treating diseases and as a salt called sal acetosella or "sorrel salt" (also known as "salt of lemon"). Growing oca tuber root caps are covered in a fluorescent slush rich in harmaline and harmine which apparently suppresses pests.[16] Creeping wood sorrel and perhaps other species are apparently hyperaccumulators of copper. The Ming Dynasty text Precious Secrets of the Realm of the King of Xin from 1421 describes how O. corniculata can be used to locate copper deposits as well as for geobotanical prospecting. It thus ought to have some potential for phytoremediation of contaminated soils.

As ornamental plants

Several species are grown as pot plants or as ornamental plants in gardens, for example, O. versicolor.

Oxalis flowers range in colour from whites to yellow, peaches, pink, or multi-coloured flowers.[17]

Some varieties have double flowers, for example the double form of O. compressus. Some varieties are grown for their foliage, such as the dark purple-leaved O. triangularis.

Species with four regular leaflets – in particular O. tetraphylla (four-leaved pink-sorrel) – are sometimes misleadingly sold as "four-leaf clover", taking advantage of the mystical status of four-leaf clover.

Selected species

_Oxalis_articulata_-_Habit.jpg.webp)

_in_Hyderabad%252C_AP_W_IMG_9725.jpg.webp)

_2.jpg.webp)

- Oxalis acetosella – common wood sorrel, stabwort

- Oxalis adenophylla – Chilean oxalis, silver shamrock

- Oxalis albicans – hairy woodsorrel, white oxalis, radishroot woodsorrel, radishroot yellow-sorrel, California yellow-sorrel

- Oxalis alpina – alpine sorrel

- Oxalis ambigua

- Oxalis articulata Savign. – pink-sorrel

- Oxalis ausensis

- Oxalis barrelieri – lavender sorrel

- Oxalis bowiei – Bowie's wood-sorrel, Cape shamrock

- Oxalis brasiliensis – Brazilian woodsorrel

- Oxalis caerulea – blue woodsorrel

- Oxalis caprina

- Oxalis corniculata – creeping wood sorrel, procumbent yellow-sorrel, sleeping beauty, chichoda bhaji (India)

- Oxalis debilis Kunth

- Oxalis decaphylla – ten-leaved pink-sorrel, tenleaf wood sorrel

- Oxalis dehradunensis

- Oxalis depressa

- Oxalis dichondrifolia – peonyleaf wood sorrel

- Oxalis dillenii Jacquin – southern yellow woodsorrel, Dillen's woodsorrel, Sussex yellow-sorrel

- Oxalis drummondii – Drummond's woodsorrel, chevron oxalis

- Oxalis ecuadorensis

- Oxalis enneaphylla – scurvy-grass sorrel

- Oxalis exilis – least yellow-sorrel

- Oxalis frutescens – shrubby wood-sorrel

- Oxalis gigantea

- Oxalis glabra – finger-leaf

- Oxalis grandis – great yellow-sorrel, large yellow woodsorrel

- Oxalis griffithii Edgew. & Hook.f.

- Oxalis hedysaroides – fire fern

- Oxalis hirta – hairy sorrel

- Oxalis illinoensis – Illinois wood-sorrel

- Oxalis inaequalis

- Oxalis incarnata L. – pale pink-sorrel

- Oxalis lasiandra – Mexican shamrock

- Oxalis latifolia Kunth – garden pink-sorrel

- Oxalis luederitzii

- Oxalis luteola Jacq.

- Oxalis magellanica G.Forst.

- Oxalis magnifica Kunth – snowdrop wood-sorrel

- Oxalis massoniana

- Oxalis megalorrhiza – fleshy yellow-sorrel

- Oxalis melanosticta

- Oxalis micrantha – dwarf woodsorrel

- Oxalis montana – mountain woodsorrel, white woodsorrel

- Oxalis nelsonii – Nelson's sorrel

- Oxalis norlindiana

- Oxalis obliquifolia

- Oxalis oregana – redwood sorrel, Oregon sorrel

- Oxalis ortgiesii Regel – fishtail oxalis

- Oxalis pennelliana

- Oxalis pes-caprae – Bermuda-buttercup, African wood-sorrel, Bermuda sorrel, buttercup oxalis, Cape sorrel, English weed, soursob, "goat's-foot", "sourgrass", soursop (not to be confused with the fruit of that name)

- Oxalis priceae – tufted yellow-sorrel

- Oxalis pulchella

- Oxalis purpurea L. – purple wood-sorrel

- Oxalis rosea Feuillée ex Jacq. – annual pink-sorrel

- Oxalis rubra A.St.-Hil. – red wood-sorrel

- Oxalis rufescens

- Oxalis rugeliana – coamo

- Oxalis schaeferi

- Oxalis spiralis – spiral sorrel, volcanic sorrel, velvet oxalis

- Oxalis stricta – common yellow woodsorrel, common yellow oxalis, upright yellow-sorrel, lemon clover, "pickle plant", "sourgrass, "yellow woodsorrel"

- Oxalis suksdorfii – western yellow woodsorrel, western yellow oxalis

- Oxalis tenuifolia – thinleaf sorrel

- Oxalis tetraphylla – four-leaved pink-sorrel, four-leaf sorrel, Iron Cross oxalis, "lucky clover"

- Oxalis triangularis – threeleaf purple shamrock

- Oxalis trilliifolia – great oxalis, threeleaf woodsorrel

- Oxalis tuberosa – oca, oka, New Zealand yam

- Oxalis valdiviensis – Chilean yellow-sorrel

- Oxalis virginea – virgin wood-sorrel

- Oxalis versicolor – candycane sorrel

- Oxalis violacea – violet wood-sorrel

- Oxalis vulcanicola – volcanic sorrel or velvet oxalis[18][19]

References

- Sunset Western Garden Book, 1995:606–607

- "Oxalis | Definition of Oxalis by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com also meaning of Oxalis". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 2021-06-12. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- Christenhusz, M. J. M.; Byng, J. W. (2016). "The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase". Phytotaxa. 261 (3): 201–217. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.261.3.1. Archived from the original on 2016-07-29. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- "Oxalis". NC State University. Archived from the original on 2021-09-01. Retrieved 2018-09-20.

- S. L. Nielsen, A. M. Simonsen (September 2011). "Photosynthesis and photoinhibition in two differently coloured varieties of Oxalis triangularis — the effect of anthocyanin content". Photosynthetica. 49 (3): 346–352. doi:10.1007/s11099-011-0042-y. S2CID 24583290.

- Mahr, Susan (March 2009). "Shamrocks, Oxalis spp". Master Gardener Program University of Wisconsin-Extension. Archived from the original on 2018-09-21. Retrieved 2018-09-20.

- Jooste, Michelle; Roets, Francois; Midgley, Guy F.; Oberlander, Kenneth C.; Dreyer, Léanne L. (2019-10-23). "Nitrogen-fixing bacteria and Oxalis – evidence for a vertically inherited bacterial symbiosis". BMC Plant Biology. 19 (1): 441. doi:10.1186/s12870-019-2049-7. ISSN 1471-2229. PMC 6806586. PMID 31646970.

- Duke, James A. (2000-11-10). Handbook of Edible Weeds: Herbal Reference Library. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-2946-3.

- "Yams". Vegetables. Archived from the original on 2021-01-20. Retrieved 2021-01-17.

- Łuczaj (2008)

- "JOAN C. et al. 1975" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-10. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "Oxalate Content of 750+ Foods". oxalate.org. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- http://oxalicacidinfo.com/ Archived 2010-01-15 at the Wayback Machine "Sheer toxicity – actual poisoning – from ingested oxalic acid is wildly unlikely. The only foodstuff that contains oxalic acid at concentrations high enough to be an actual toxicity risk is the leaves – not the stalks, which is what one normally eats – of the rhubarb plant. (And you'd need to eat an estimated 11 pounds (5kg) of rhubarb leaves at one sitting for a lethal dose, though you'd be pretty sick with rather less.)" On the other hand: "The second effect is not chemical but mechanical: the crystals of oxalate, very small but very sharp, can be large enough to irritate the body. The chiefest and most famous example of this is kidney stones--probably 80% of kidney stones derive from calcium oxalate."

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Oxalic acid poisoning

- http://dietary-supplements.info.nih.gov/factsheets/calcium.asp Archived 2009-09-23 at the Wayback Machine "Other components in food: phytic acid and oxalic acid, found naturally in some plants, bind to calcium and can inhibit its absorption. Foods with high levels of oxalic acid include spinach, collard greens, sweet potatoes, rhubarb, and beans. Among the foods high in phytic acid are fiber-containing whole-grain products and wheat bran, beans, seeds, nuts, and soy isolates. The extent to which these compounds affect calcium absorption varies. Research shows, for example, that eating spinach and milk at the same time reduces absorption of the calcium in milk. In contrast, wheat products (with the exception of wheat bran) do not appear to have a negative impact on calcium absorption. For people who eat a variety of foods, these interactions probably have little or no nutritional consequence and, furthermore, are accounted for in the overall calcium DRIs, which take absorption into account."

- Bais et al. (2002, 2003)

- "A daring passion". 28 August 2009. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- "Classification | USDA PLANTS". plants.usda.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-01-17. Retrieved 2021-01-17.

- "Again: Taxonomy Of Yellow-Flowered Caulescent Oxalis (Oxalidaceae) In Eastern North America J. Bot. Res. Inst. Texas 3(2): 727 – 738. 2009" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

Further reading

- Bais, Harsh Pal; Park, Sang-Wook; Stermitz, Frank R.; Halligan, Kathleen M. & Vivanco, Jorge M. (2002): Exudation of fluorescent β-carbolines from Oxalis tuberosa L. roots. Phytochemistry 61(5): 539–543. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00235-2 PDF fulltext

- Bais, Harsh Pal; Vepachedu, Ramarao & Vivanco, Jorge M. (2003): Root specific elicitation and exudation of fluorescent β-carbolines in transformed root cultures of Oxalis tuberosa. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 41(4): 345–353. doi:10.1016/S0981-9428(03)00029-9 Preprint PDF fulltext

- Łuczaj, Łukasz (2008): Archival data on wild food plants used in Poland in 1948. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 4: 4. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-4-4 PDF fulltext

_(19067830888).jpg.webp)