ZX Spectrum

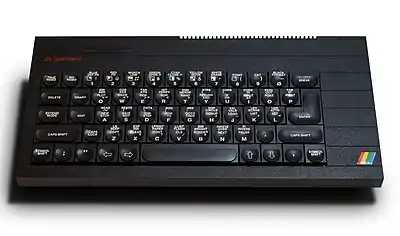

The ZX Spectrum (UK: /zɛd ɛks/) is an 8-bit home computer developed and marketed by Sinclair Research. It was first released in the United Kingdom on 23 April 1982. Many official and unofficial clones were released around the world in the following years, most notably in Europe, the United States, and Eastern Bloc countries.

| |

An issue 2 1982 ZX Spectrum | |

| Developer | Sinclair Research |

|---|---|

| Type | Home computer |

| Generation | 8-bit |

| Release date | |

| Introductory price | UK: £125 (16KB) / £175 (48KB),[2] US: $200, ESP: Pta44,250 |

| Discontinued | 1992[3] |

| Units sold | 5 million[4] |

| Media | Compact Cassette, ZX Microdrive, 3-inch floppy disk on Spectrum +3 |

| Operating system | Sinclair BASIC |

| CPU | Z80A (or equivalent) @ 3.5 MHz |

| Memory | 16 KB / 48 KB / 128 KB (IEC: KiB) |

| Display | PAL RF modulator out, 256 x 192, 15 colours |

| Graphics | ULA |

| Sound | Beeper |

| Predecessor | ZX81 |

| Successor | QL |

The machine was the brainchild of English entrepreneur and inventor Sir Clive Sinclair. Referred to during development as the ZX81 Colour, the ZX Spectrum was designed by a small team in Cambridge. It was designed to be small, simple, and most importantly inexpensive, with as few components as possible. The addendum 'Spectrum' was chosen to highlight the machine's colour display, which differed from the black and white display of its predecessor, the ZX81. Its distinctive case, rainbow motif and rubber keyboard were designed by Rick Dickinson. Video output is transmitted to a television set rather than a dedicated monitor, while software is loaded and saved onto compact audio cassettes.

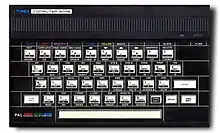

It was initially distributed through mail order, but after severe backlogs the machine was sold through High Street chains in the United Kingdom. It was released in the United States as the Timex Sinclair 2068 in 1983, and in some parts of Europe as the Timex Computer 2048. Ultimately the Spectrum was released as six different models, ranging from the entry level with 16 KB RAM released in 1982 to the ZX Spectrum +3 with 128 KB RAM and built-in floppy disk drive in 1987. Throughout its life, the machine primarily competed with the Commodore 64, BBC Micro, Dragon 32, and the Amstrad CPC range. Not counting unofficial clones, the machine sold over 5 million units worldwide. Over 24,000 different software titles were released for the ZX Spectrum.[1]

The ZX Spectrum played a pivotal role in the early history of personal computing and video gaming, leaving an enduring legacy that influenced generations. Its introduction led to a boom in companies producing software and hardware,[5] the effects of which are still seen. It was among the first home computers aimed at a mainstream audience, with some crediting it as being responsible for launching the British information technology industry.[6] It remains Britain's best-selling computer.[7][8] The machine was officially discontinued in 1992.

History

Background

The ZX Spectrum was conceived and designed by English entrepreneur and inventor Clive Sinclair, who was well known for his eccentricity and pioneering ethic.[9] On 25 July 1961, three years after passing his A-levels, he founded Sinclair Radionics Ltd as a vehicle to advertise his inventions and buy components.[10] In 1972, Sinclair had competed with Texas Instruments to produce the world's first pocket calculator, the Sinclair Executive.[11] By the mid 1970s, Sinclair Radionics was producing handheld electronic calculators, miniature televisions, and the ill-fated digital Black Watch wristwatch.[12] Due to financial losses, Sinclair sought investors from the National Enterprise Board (NEB), who had bought a 43% interest in the company and streamlined his product line. Sinclair's relationship with the NEB had worsened, however, and by 1979 it opted to break up Sinclair Radionics entirely,[13] selling off its television division to Binatone and its calculator division to ESL Bristol.[14]

After incurring a £7 million investment loss, Sinclair was given a golden handshake and an estimated £10,000 severance package.[11][15] He had a former employee, Christopher Curry, establish a "corporate lifeboat" company named Science of Cambridge Ltd, in July 1977, called such as they were located near the University of Cambridge.[16] By this time inexpensive microprocessors had started appearing on the market, which prompted Sinclair to start producing the MK14, a computer teaching kit which sold well at a very low price.[17] Encouraged by this success, Sinclair renamed his company to Sinclair Research, and started looking to manufacture personal computers. Keeping the cost low was essential for Sinclair to avoid his products from becoming outpriced by American or Japanese equivalents as had happened to several of the previous Sinclair Radionics products.[11] On 29 January 1980, the ZX80 home computer was launched to immediate popularity; notable for being one of the first computers available in the United Kingdom for less than £100.[18][19] The company conducted no market research whatsoever prior to the launch of the ZX80; according to Sinclair, he "simply had a hunch" that the public was sufficiently interested to make such a project feasible and went ahead with ordering 100,000 sets of parts so that he could launch at high volume.[20]

On 5 March 1981, the ZX81 was launched worldwide to immense success with more than 1.5 million units sold,[21] 60% of which was outside Britain.[22] According to Ben Rosen, by pricing the ZX81 so low, the company had "opened up a completely new market among people who had never previously considered owning a computer".[23] Its release heralded the point when computing in Britain became an activity for the general public rather than the preserve of businessmen and hobbyists. The ZX81's commercial success made Sinclair Research one of Britain's leading computer manufacturers, with Sinclair himself reportedly "amused and gratified" by the attention the machine received.[24]

Development

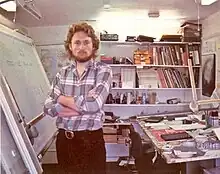

Development of the ZX Spectrum began in September 1981, a few months after the release of the ZX81. Sinclair resolved to make his own products obsolete before his rivals developed the products that would do so, thus seeking to make the technology as cheap as possible. Architecture from the ZX80 and ZX81 were recycled to ensure a speedy and cost-effective manufacturing process. The team consisted of 20 engineers housed in a small office at 6 King's Parade, Cambridge.[25] During early production, the machine was known as the ZX81 Colour or the ZX82 to highlight the machine's colour display, which differed from the black and white of its predecessors. The addendum 'Spectrum' was added later on, to emphasise its 15-colour palette.[26] According to Sinclair, the team had the concept of using a single bank of random access memory as opposed to having separate data areas for audio and video. Much of the code was written by computer scientist Steve Vickers from Nine Tiles,[27] who compiled all control routines on Sinclair BASIC, a custom interpreter of the general purpose BASIC programming language. The interpreter enabled all subroutines to be loaded onto a very small amount of read-only memory (ROM). By taking advantage of pre-existing television sets and stereo speakers people "would already have" in their homes, Sinclair Research did not need to manufacture additional audiovisual equipment. Aside from a new crystal oscillator and extra chips to add additional kilobytes of memory,[28] the ZX Spectrum was, as quoted by Sinclair's marketing manager, essentially a "ZX81 with colour".[25]

Chief engineer Richard Altwasser was responsible for the ZX Spectrum's processor design. His main contribution was the design of the graphics mode using less than 7 kilobytes of memory, and together with Vickers, wrote most of the ROM code. Lengthy discussions between Altwasser and Sinclair engineers resulted in a broad agreement that the ZX Spectrum must have high-resolution graphics, 16 kilobytes of memory, an improved cassette interface, and an impressive colour palette.[29] To achieve this, the team had to divorce the central processing unit (CPU) away from the main display to enable it to work at full efficiency – a method which contrasted with the ZX81's integrated CPU.[29] The inclusion of colour to the display proved a major obstacle to the engineers. A Teletext-like approach was briefly considered, in which each line of text would have colour-change codes inserted into it. However this was ruled out as it was deemed unsuitable for high-resolution graphs or diagrams that involved multiple colour changes. Altwasser devised the idea of allocating a colour attribute to each character position on the screen. This ultimately used six bits of memory; three bits to provide any one of eight foreground colours and three bits for the eight background colours, for each character position. Overall, the system took up slightly less than 7 kilobytes of memory, leaving an additional 9 kilobytes to write programs — a figure the team was pleased with.[30]

A divergence of perspectives between Nine Tiles and Sinclair Research marred the development process, leading to disagreements on the optimal course of action. Notably, Vickers highlighted Sinclair's emphasis on expediting the release of the Spectrum, primarily by minimising alterations from the ZX81. The software architecture of the ZX80, tailored for a severely constrained memory system, proved unsuitable for the enhanced processing demands of the ZX Spectrum. Sinclair's precedent with the ZX81 indicated a reluctance to overhaul the ZX80 code, favouring instead the incorporation of expansion modules onto the existing framework. However, this approach, deemed acceptable for the ZX81, raised concerns within Nine Tiles regarding its potentially detrimental impact on the more sophisticated Spectrum.[31]

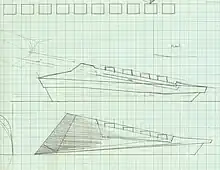

The distinctive wedge-shaped case and colourful design of the ZX Spectrum was the brainchild of Rick Dickinson, a young British industrial designer who had been hired by Sinclair to design the ZX81. Dickinson was tasked to design a sleeker and more "marketable" appearance to the new machine, whilst ensuring all 192 BASIC functions could fit onto 40 physical keys.[25] Early sketches from August 1981 showed the case was to be more angular and wedge-like, in similar vein to an upgraded ZX81 model. Dickinson later settled on a flatter design with a raised rear section and rounded sides in order to depict the machine as "more advanced" as opposed to a mere upgrade. In drawing up potential logos, Dickinson proposed a series of different logotypes which all featured rainbow slashes across the keyboard.[32]

Designing the Spectrum's rubber keyboard was minimalised from several hundred components to a conventional moving keyboard down to "four to five" moving parts using a new technology.[33] The keyboard was still undergoing changes as late as February 1982; some sketches included a roundel-on-square key design which was later featured on the later Spectrum+ model.[32] Dickinson recalled in 2007 that "everything was cost driven" and that the minimalist, Bauhaus approach to the Spectrum gave it an elegant yet "[non] revolutionary" form.[3] The drawing board on which Dickinson designed the ZX Spectrum is now on display in the Science Museum in London.[34][35]

The need for an improved cassette interface was apparent from the number of complaints received by ZX81 users who encountered problems when trying to save and load programs. To remedy this, the team increased the number of cycles of which the machine read cassettes, and implemented periods of constant tones which allowed the cassette recorder's automatic gain control to settle itself down, eliminating hisses on the tape.[29] Altwasser considered the improved tape mechanism to be his proudest achievement; originally the team aimed for the getting the ZX Spectrum to operate at 1000 baud, but succeeded in getting it to work at a considerably faster 1500 baud.[29]

As with its predecessors, the ZX Spectrum was manufactured in Dundee, Scotland by Timex Corporation at the company's Dryburgh factory.[36][37] Timex had not been an obvious choice of manufacturing subcontractor, as prior to the manufacture of the ZX80, the company had little experience in assembling electronics. It was a well-established manufacturer of mechanical watches but was facing a crisis at the beginning of the 1980s. Profits had dwindled to virtually zero as the market for watches stagnated in the face of competition from the digital and quartz watches. Recognising the trend, Timex's director, Fred Olsen, determined that the company would diversify into other areas and signed a contract with Sinclair.[38]

Launch

The ZX Spectrum was officially revealed before journalists by Sinclair at the Churchill Hotel in Marylebone, London on 23 April 1982.[32][39] Later that week, the machine was officially presented in a "blaze of publicity" at the Earl's Court Computer Show in London,[40][41] and the ZX Microfair in Manchester.[42] The ZX Spectrum was launched with two models; a 16KB 'basic' version, and an enhanced 48KB variant.[2] The former model had an undercutting price of £125, significantly lower than its main competitor the BBC Micro, whilst the latter model's price of £175 was comparable to a third of an Apple II computer.[43][44] Upon release, the keyboard surprised many users due to its use of rubber keys, described as offering the feel of "dead flesh".[32][45] Sinclair himself remarked that the keyboard's rubber mould was "unusual", but consumers were undeterred.[46]

Despite very high demand, Sinclair Research was "notoriously late" in delivering the ZX Spectrum. Their practice of offering mail-order sales before units were ready ensured a constant cash flow, but meant a lacking distribution.[26] Nigel Searle, the newly-appointed chief of Sinclair's computer division, said in June 1982 the company had no plans to stock the new machine in WHSmith, which was at the time Sinclair's only retailer.[47] Searle explained that the mail-order system was in place due to there being no "obvious" retail outlets in the United Kingdom which could sell personal computers, and it made "better sense" financially to continue selling through mail-order.[48] The company's conservative approach to distributing the machine was criticised,[26] with disillusioned customers telephoning and writing letters.[49][50] Demand sky-rocketed beyond Sinclair's planned 20,000 monthly unit output to a backlog of 30,000 orders by July 1982. Due to a scheduled holiday at the Timex factory that summer, the backlog had risen to 40,000 units. Sinclair issued a public apology in September that year,[32] and promised that the backlog would be cleared by the end of that month.[49] Supply did not return to normal until the 1982 Christmas season, however.[51]

With the arrival of the more inexpensive Issue 2 motherboard, production rapidly increased. A further 500,000 units shipped throughout the remainder of 1982 and into 1983, with the vast majority of them being sold directly by Sinclair itself. The introduction of the Issue 3 motherboard bolstered the number of sold units to a total of three million by the end of 1983. By this point the exclusive distribution deal with WHSmith expired,[52] opening the ZX Spectrum to prominent High Street chains such as Boots, Currys, and John Menzies.[32] Sales of the ZX Spectrum reached 200,000 in its first nine months[53] rising to 300,000 for the whole of the first year.[54] By August 1983 total sales in the UK and Europe had exceeded 500,000[55] with the millionth Spectrum manufactured on 9 December 1983.[56]

The machine was also backed by a successful albeit "unusual" marketing campaign as the company refused to set a pre-determined budget on advertising. Searle recalled that they were prepared to spend "as much as possible" on marketing as long as the outcome produced profitable sales. In 1981, Sinclair Research had spent just over £5 on advertising, whereas after the launch of the ZX Spectrum it was projected that they would invest more than £10 million.[48]

In July 1983, the ZX Spectrum was launched in the United States as the more enhanced Timex Sinclair 2068. Advertisements described it as offering 72 kilobytes of memory, having a full range of colour and sound for a price under $200.[57] Sales proved poor and Timex Sinclair collapsed the following year.[32][58]

Success and market domination

A crucial part of the company's marketing strategy was to implement regular price-cutting at strategic intervals to maintain market share. Ian Adamson and Richard Kennedy noted that Sinclair's method was driven by securing his leading position through "panicking" the competition. While most companies at the time reduced prices of their products while their market share was dwindling, Sinclair Research discounted theirs shortly after sales had peaked, throwing the competition into "utter disarray".[59] Sinclair Research made a profit of £14 million in 1983, compared to £8.5 million the previous year. Turnover doubled from £22 million to £54.5 million, which equated to roughly £1 million for each person employed directly by the company.[60]

Clive Sinclair became a focal point during the ZX Spectrum's marketing campaign by putting a human face onto the business. Sinclair Research was portrayed in the media as a "plucky" British challenger taking on the technical and marketing might of giant American and Japanese corporations. As David O'Reilly noted in 1986, "by astute use of public relations, particularly playing up his image of a Briton taking on the world, Sinclair has become the best-known name in micros."[61] The media latched onto Sinclair's image; his "Uncle Clive" persona is said to have been created by the gossip columnist for Personal Computer World.[62] The press praised Sinclair as a visionary genius, with The Sun lauding him as "the most prodigious inventor since Leonardo da Vinci". Adamson and Kennedy wrote that Sinclair outgrew the role of microcomputer manufacturer and "accepted the mantle of pioneering boffin leading Britain into a technological utopia".[63] Sinclair's contribution to the technology sector resulted in him being knighted upon the recommendation of Margaret Thatcher in the Queen's 1983 Birthday Honours List.[64][65][66]

The United Kingdom was largely immunised from the effects of the video game crash of 1983, in due part to saturation of home computers such as the ZX Spectrum.[67][68][69]The microcomputer market continued to grow and game development was unhindered despite the turbulence in the North American and Japanese markets. Indeed, computer games remained the dominant sector of the British home video game market up until they were surpassed by Sega and Nintendo consoles in 1991.[70] By the end of 1983 there were more than 450 companies in Britain selling video games on cassette, compared to 95 the year before.[71] An estimated 10,000 to 50,000 people, mostly young men, were developing games out of their homes based on advertisements in popular magazines. The growth of video games during this period was comparable to the punk subculture, fuelled by young people making money from their games.[72]

Sinclair's claims that his technology would surpass IBM's personal computers were taken seriously. In an interview with Practical Computing magazine, Sinclair was confident that the ZX Spectrum's compact size and fewer chips would set the precedent for future computers around the world.[73] By the mid 1980s, Sinclair Research's share of the British home computer market had climbed to a high of 40 per cent.[74] Sales in the 1984 Christmas season were described as "extremely good" with the ZX Spectrum outselling every other microcomputer, including the Commodore 64, its fiercest rival.[75] In early 1985 the British press reported the home computer boom to have ended,[76] leaving many companies slashing prices of their hardware to anticipate lower sales.[75] Despite this, celebration of Sinclair's success in the computing market continued at the Which Computer? show in Birmingham, where the fifth-million ZX Spectrum was issued as a prize.[75]

Later years and company decline

The ZX Spectrum's successor, the Sinclair QL, was officially announced on 12 January 1984, shortly before the Apple Macintosh went on sale.[77] Contrasting with its predecessors, the QL was aimed at more serious, professional home users.[78] It suffered from several design flaws; fully operational QLs were not available until the late summer, and complaints against Sinclair concerning delays were upheld by the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) in May of that year. Particularly serious were allegations that Sinclair was cashing cheques months before machines were shipped. By autumn 1984, Sinclair was still publicly forecasting that it would be a "million seller" and that 250,000 units would be sold by the end of the year.[79] QL production was suspended in February 1985, and the price was halved by the end of the year.[80] It ultimately flopped, selling a mere 150,000 units.[81]

The ZX Spectrum+, a rebranded ZX Spectrum featuring a QL-like keyboard, was introduced in October 1984 and made available in WHSmith's stores the day after its launch. Retailers stocked the device in high quantities, anticipating robust Christmas sales. Nevertheless, the product did not perform as well as projected, leading to a significant drop in Sinclair's income from orders in January, as retailers were left with surplus stock. The Spectrum+ retained the identical technical specifications as the original Spectrum. Subsequently, an upgraded model, the ZX Spectrum 128, was released in Spain in September 1985, with development financed by the Spanish distributor Investrónica.[82] The launch of this model in the UK was postponed until January 1986 due to the substantial leftover inventory of the prior model.[83]

Despite the continued domination of home computer market with the ZX Spectrum, Sinclair hoped to repeat his success in the fledgling electric vehicle market, which he saw as ripe for a new approach. On 10 January 1985, Sinclair unveiled the Sinclair C5, a small one-person battery electric recumbent tricycle. It marked the culmination of Sir Clive's long-running interest in electric vehicles.[84] The C5 turned out to be a significant commercial failure, selling only 17,000 units and losing Sinclair £7 million. It has since been described as "one of the great marketing bombs of postwar British industry".[85] The ASA ordered Sinclair to withdraw advertisements for the C5 after finding that the company's claims about its safety could not be proved or justified.[86]

The combined failures of the C5 and QL caused investors to lose confidence in Sinclair's judgement. In May 1985, Sinclair Research announced their intention to raise an additional £10 to £15 million to restructure the organisation. Given the loss of confidence in the company, securing the funds proved to be a challenging task. In June 1985, business magnate Robert Maxwell disclosed a takeover bid for Sinclair Research through Hollis Brothers, a subsidiary of his Pergamon Press.[87] However, the deal was terminated in August 1985.[74] The future of Sinclair Research remained uncertain until 7 April 1986, when the company sold their entire computer product range, along with the "Sinclair" brand name, to Alan Sugar's Amstrad for £5 million.[88] The takeover sent ripples through the London Stock Exchange, but Amstrad's shares soon recovered, with one stock broker affirming that "the City appears to have taken the news in its stride".[89] Amstrad's acquisition of the brand name saw the release of three ZX Spectrum models throughout the late 1980s, each with varying improvements.[90]

By 1990, Sinclair Research consisted of Sinclair and two other employees down from 130 employees at its peak in 1985.[91] The ZX Spectrum was officially discontinued in 1992, after ten years on the market.[51][3] Sinclair Research thereafter continued to exist as a one-man company, marketing Sir Clive Sinclair's inventions until his death in September 2021.

Hardware

Technical specifications

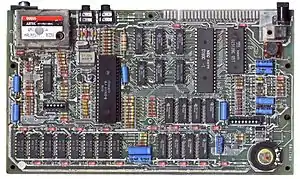

The main microprocessor is the Zilog Z80, an 8-bit central processing unit (CPU) with a clock rate of 3.5 MHz. The original model features 16 KB (16,384 bytes) of ROM and either 16 KB or 48 KB of RAM.[5]

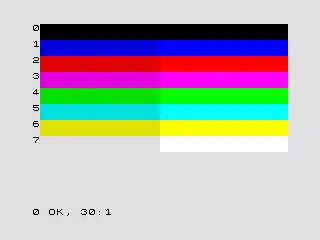

Video output is channelled through an RF modulator, intended for use with contemporary television sets, to provide a simple colour graphic display. Text is displayed using a grid of 32 columns × 24 rows of characters from the ZX Spectrum character set or from a set provided within an application. The machine features a colour palette of 15 shades, comprising seven colours at two levels of brightness each, along with black.[92] The image resolution is 256×192 pixels, subject to the same colour limitations.[93] To optimise memory usage, colour is stored separately from the pixel bitmap in a low resolution, 32×24 grid overlay, corresponding to the character cells. In practical terms, this means that all pixels within an 8x8 character block share one foreground colour and one background colour. Altwasser received a patent for this design.[94]

An "attribute" consists of a foreground and a background colour, a brightness level (normal or bright) and a flashing "flag" which, when set, causes the two colours to swap at regular intervals.[93] This scheme leads to what was dubbed "colour clash" or attribute clash, where a desired colour of a specific pixel could not necessarily be selected. This became a distinctive feature of the Spectrum, requiring programs, especially games, to be designed with this limitation in mind. In contrast, other machines available at the same time, such as the Amstrad CPC or the Commodore 64, did not suffer from this limitation. While the Commodore 64 also employed colour attributes, it utilised a special multicolour mode and hardware sprites to circumvent attribute clash.[95]

Sound output is produced through a built-in beeper capable of generating a single channel with ten octaves.[96] It is controlled by a single EAR bit, located on port 0xFE.[97] By toggling the EAR bit (0xFE port) on and off, simple sounds are generated. Later software became available that allowed for two-channel sound playback. The machine includes an expansion bus edge connector and 3.5 mm audio in/out ports, facilitating the connection of a cassette recorder for loading and saving programs and data. The EAR port has a higher output than the MIC and is recommended for headphones, while the MIC port is intended for attachment to other audio devices as a line-in source.[98]

The ZX Spectrum integrated various design elements from the ZX81. The ROM code, responsible for tasks such as floating point calculations and expression parsing, exhibited significant similarities, although a few outdated ZX81 routines remained in the Spectrum ROM.[99] The keyboard decoding and cassette interfaces were nearly identical, although the latter was programmed for higher-speed loading and saving. The central Uncommitted Logic Array (ULA) integrated circuit shares some resemblance with the ZX81's, however it features a fully hardware-based television raster generator with colour support. This enhancement indirectly provided the new machine with roughly four times the processing power of the ZX81, as the Z80 was relieved of video generation tasks. An initial ULA design flaw occasionally led to incorrect keyboard scanning, which was resolved by adding a "dead cockroach" (a small circuit board mounted upside down next to the CPU) in Issue 1 ZX Spectrums.[44]

Firmware

The machine's Sinclair BASIC interpreter is stored in read-only memory (along with essential system routines) and was authored by Steve Vickers under a contract with Nine Tiles Ltd. The keyboard is imprinted with BASIC keywords. For instance, when in programming mode, pressing the letter "G" inserts the BASIC command GO TO.[100]

The BASIC interpreter is derived from the one used on the ZX81, and a ZX81 BASIC program can be entered into a ZX Spectrum with minimal modifications. However, Spectrum BASIC introduced numerous additional features, enhancing its usability. The ZX Spectrum character set was expanded compared to that of the ZX81, which lacked lowercase letters. Spectrum BASIC incorporated extra keywords for advanced display and sound functionality, and it supported multi-statement lines. The cassette interface is significantly more advanced than the ZX81, enabling savings and loadings at approximately five times the speed (1500 bits per second as opposed to 307 bits per second).[101] Unlike the ZX81, the Spectrum can maintain the TV display during tape storage and retrieval operations. In addition to program storage, the Spectrum had the capability to save the contents of arrays, screen memory, and any specified range of memory addresses.[102]

Sinclair Research models

ZX Spectrum 16K/48K

The original ZX Spectrum is remembered for its rubber chiclet keyboard, diminutive size and distinctive rainbow motif. It was originally released on 23 April 1982 with 16 KB of RAM for £125 (equivalent to £469 in 2021) or with 48 KB for £175 (equivalent to £657 in 2021);[104] these prices were reduced to £99 (equivalent to £355 in 2021) and £129 (equivalent to £463 in 2021) respectively in 1983.[105] Owners of the 16 KB model could purchase an internal 32 KB RAM upgrade, which for early "Issue 1" machines consisted of a daughterboard. Later issue machines required the fitting of 8 dynamic RAM chips and a few TTL chips. Users could mail their 16K Spectrums to Sinclair to be upgraded to 48 KB versions. Later revisions contained 64 KB of memory but were configured such that only 48 KB were usable.[106] External 32 KB RAM packs that mounted in the rear expansion slot were available from third parties. Both machines had 16 KB of onboard ROM.[26]

An "Issue 1" ZX Spectrum can be distinguished from later models by the colour of the keys – light grey for Issue 1, blue-grey for later machines.[107] Although the official service manual states that approximately 26,000 of these original boards were manufactured,[108] subsequent serial number analysis shows that only 16,000 were produced, almost all of which fell in the serial number range 001-000001 to 001-016000.[109] An online tool now exists to allow users to ascertain the likely issue number of their ZX Spectrum by inputting the serial number.[110]

Within the original iterations of the 16 and 48K models, an internal speaker with severely restricted capabilities served as the audio output. This speaker, capable of producing just one note at a time, was governed by the BASIC command 'BEEP', where programmers could manipulate parameters for pitch and duration.[111] Furthermore, the processor remained occupied exclusively with the BASIC BEEPs until their completion, limiting concurrent operations. Despite these constraints, it marked a significant step forward from the ZX81, which lacked any sound capabilities. Resourceful programmers swiftly devised workarounds; its rudimentary audio functionality compelled developers to explore unconventional methods such as programming the beeper to emit multiple pitches.[112]

These models experienced numerous changes to its motherboard design throughout its life; mainly to improve manufacturing efficiencies, but also to correct bugs from previous boards. Another issue was with the Spectrum's power supply. In March 1983, Sinclair issued an urgent recall warning for all owners of models bought after 1 January 1983.[113] Plugs with a plain (rather than textured) surface were at risk of causing shock, and were asked to be sent back to a warehouse in Cambridgeshire which would supply a replacement within 48 hours.[114][115]

ZX Spectrum+

Development of the ZX Spectrum+ began in June 1984,[116] and was released on 15 October that year.[117][118] This 48 KB Spectrum (development code-name TB[116]) introduced a new QL-style case with an injection-moulded keyboard and a reset button that functions as a switch shorting across the CPU reset capacitor. Electronically, it was identical to the previous 48 KB model. It was possible to swap the system boards between the original case and the Spectrum+ case. It retailed for £179.[119] A DIY conversion-kit for older machines was available. Initially, the machine outsold the rubber-key model 2:1;[116] however, some retailers reported a failure rate of up to 30%, compared with a more typical 5–6% for the older model.[118] In early 1985, the original Spectrum was officially discontinued, and the ZX Spectrum+ was reduced in price to £129.[75]

ZX Spectrum 128

In 1985, Sinclair developed the ZX Spectrum 128 (code-named Derby) in conjunction with their Spanish distributor Investrónica (a subsidiary of El Corte Inglés department store group).[120][121][122] Investrónica had helped adapt the ZX Spectrum+ to the Spanish market after their government introduced a special tax on all computers with 64 KB RAM or less,[123] and a law which obliged all computers sold in Spain to support the Spanish alphabet and show messages in Spanish.[124]

The appearance of the ZX Spectrum 128 is similar to the ZX Spectrum+, with the exception of a large external heatsink for the internal 7805 voltage regulator added to the right hand end of the case, replacing the internal heatsink in previous versions. This external heatsink led to the system's nickname, "The Toast Rack".[125] New features included 128 KB RAM with RAM disc commands 'save !"name"', three-channel audio via the AY-3-8912 chip, MIDI compatibility, an RS-232 serial port, an RGB monitor port, 32 KB of ROM including an improved BASIC editor, and an external keypad.[112]

The machine was simultaneously presented for the first time and launched in September 1985 at the SIMO '85 trade show in Spain, with a price of 44,250 pesetas. Sinclair first unveiled the ZX Spectrum 128 at the The May Fair Hotel's Crystal Rooms in London, where he acknowledged that entertainment was the most common use of home computers. Due to the large number of unsold Spectrum+ models, Sinclair decided not to start it selling in the United Kingdom until January 1986 at a price of £179.[126][69]

The Zilog Z80 processor used in the Spectrum has a 16-bit address bus, which means only 64 KB of memory can be directly addressed. To facilitate the extra 80 KB of RAM the designers used bank switching so the new memory would be available as eight pages of 16 KB at the top of the address space. The same technique was used to page between the new 16 KB editor ROM and the original 16 KB BASIC ROM at the bottom of the address space.[127]

The new sound chip and MIDI out abilities were exposed to the BASIC programming language with the command PLAY and a new command SPECTRUM was added to switch the machine into 48K mode, keeping the current BASIC program intact (although there is no command to switch back to 128K mode). To enable BASIC programmers to access the additional memory, a RAM disk was created where files could be stored in the additional 80 KB of RAM. The new commands took the place of two existing user-defined-character spaces causing compatibility problems with certain BASIC programs.[128] Unlike its predecessors, it has no internal speaker, being produced from the television speaker instead.[129]

Amstrad models

ZX Spectrum +2

.jpg.webp)

The ZX Spectrum +2 marked Amstrad's entry into the Spectrum market shortly after their acquisition of the Spectrum range and "Sinclair" brand in 1986. This machine featured a brand-new grey case with a spring-loaded keyboard, dual joystick ports, and an integrated cassette recorder known as the "Datacorder," akin to the Amstrad CPC 464. However, it was largely identical to the ZX Spectrum 128 in most aspects. The main menu screen did not include the "Tape Test" option found in the Spectrum 128, and the ROM was adjusted to incorporate a new 1986 Amstrad copyright message. Production costs were reduced, leading to a retail price drop to £139–£149.[90]

The new keyboard did not feature the BASIC keyword markings seen on earlier Spectrums, except for the keywords LOAD, CODE, and RUN, which were useful for loading software. Instead, the +2 introduced a menu system, almost identical to that of the ZX Spectrum 128, allowing users to switch between 48K BASIC programming with keywords and 128K BASIC programming, where all words, both keywords and others, needed to be typed out in full (though keywords were still stored internally as one character each). Despite these changes, the layout remained identical to that of the 128.[130]

The ZX Spectrum +2 used a power supply similar to the grey ZX Spectrum+ and 128 power supply.[131]

ZX Spectrum +3

The ZX Spectrum +3, which was launched in 1987, bore a resemblance to the +2 model but introduced a built-in 3-inch floppy disk drive instead of the tape drive. Initially priced at £249[132], it later retailed for £199.[133] It was the only Spectrum model capable of running the CP/M operating system without additional hardware.

The +3 model saw the addition of two more 16 KB ROMs, with one accommodating the second part of the reorganised 128 ROM and the other hosting the +3's disk operating system, a modified version of Amstrad's PCWDOS known as +3DOS.

These significant alterations caused a series of incompatibilities, such as the removal of several lines on the expansion bus edge connector (video, power, and IORQGE), resulting in complications for various external devices like the VTX5000 modem, which could be used with the aid of the "FixIt" device. Additionally, changes in memory timing led to certain RAM banks being contended, causing failures in high-speed colour-changing effects. The keypad scanning routines from the ROM were also eliminated, rendering some older 48K and 128K games incompatible with the machine. The ZX Interface 1 was also rendered incompatible due to disparities in ROM and expansion connectors, making it impossible to connect and use the Microdrive units.[134]

Unlike its predecessors, the ZX Spectrum +3 power supply utilised a DIN connector and featured "Sinclair +3" branding on the case.[135]

Production of the +3 was discontinued in December 1990, reportedly in response to Amstrad's relaunch of their CPC range, with an estimated 15% of ZX Spectrums sold being +3 models at the time. The +2B model, the only other model still in production, continued to be manufactured, as it was believed not to be in direct competition with other computers in Amstrad's product range.[136][137]

ZX Spectrum +2A, +2B and +3B

.jpg.webp)

The ZX Spectrum +2A was a new version of the Spectrum +2[138] using the same circuit board as the Spectrum +3.[138][139] It was sold from late 1988 and unlike the original grey +2 was housed inside a black case.[138][139] The Spectrum +2A/+3 motherboard (AMSTRAD part number Z70830) was designed so that it could be assembled with a +2 style "datacorder" connected instead of the floppy disk controller.[140] The power supply of the ZX Spectrum +2A used the same pinout as the +3 and has "Sinclair +2" written on the case.[141]

1989 saw the release of the ZX Spectrum +2B and ZX Spectrum +3B. They are functionally similar in design to the Spectrum +2A and +3,[142] though changes to the generation of the audio output signal were made to resolve problems with clipping.[143] The +2B board has no provision for floppy disk controller circuitry, while the +3B motherboard has no provision for connecting an internal tape drive. Production of all Amstrad Spectrum models ended in 1992.[3]

Clones and re-creations

Official clones

Sinclair Research granted a licence for the ZX Spectrum design to the Timex Corporation in the United States. Timex marketed several computer models under the Timex Sinclair brand. They introduced an enhanced variant of the original Spectrum in the US, known as the Timex Sinclair 2068. This upgraded model features improvements in sound, graphics, and various other aspects. However, Timex's versions were generally not compatible with Sinclair systems.

Following Amstrad's acquisition of Sinclair Research's computer business, Sir Clive Sinclair retained the rights to the Pandora project. This project eventually evolved into the Cambridge Z88, which was launched in 1987.[144] The ill-fated Pandora portable Spectrum incorporated a ULA that introduced the high-resolution video mode originally pioneered in the Timex Sinclair 2068. The Pandora was designed with a flat-screen monitor and Microdrives, intended as Sinclair's solution for portable business computing.

Starting in 1984, Timex of Portugal developed and produced several Timex branded computers, including the Timex Computer 2048, which was highly compatible with the Sinclair ZX Spectrum 48K. This model saw significant success in both Portugal and Poland.[145] While an NTSC version was initially intended for release in the United States, it was ultimately only sold in Chile, Ecuador, and Argentina.

Timex of Portugal produced a PAL region-compatible version of the Timex Sinclair 2068, known as the Timex Computer 2068. This variant features distinct buffers for both the ULA and the CPU, significantly enhancing compatibility with ZX Spectrum software compared to the North American model. The modification of the expansion port ensured 100% compatibility with ZX Spectrum's, eliminating the need for a "Twister Board" expansion required by the Timex Sinclair 2068 to support ZX Spectrum expansion hardware. Additionally, the AY sound output in the TC 2068 was directed to the monitor/TV speakers rather than the internal tweeter.

Software developed for the Portuguese-made 2068 remained fully compatible with its North American variant, as the ROMs were left unaltered. Timex of Portugal further created a ZX Spectrum "emulator" in cartridge form that precisely mapped the first 16 KB, akin to the earlier 2048 computer. Several other upgrades were introduced, including a BASIC64 cartridge enabling the TC 2068 to utilise high-resolution (512x192) modes.

Timex's Portuguese division was also in the process of developing a successor to the 2068 named the Timex Computer 3256, featuring a Z80A CPU and 256 KB of RAM.[146] The planned model was intended to have both ZX Spectrum BASIC and a CP/M operating modes. However, the company terminated its development as the 8-bit market ceased to be profitable by the end of 1989. Only one fully functional prototype of the 3256 was completed.[147]

In India, Deci Bells Electronics Limited[148] introduced a licensed version of the Spectrum+ in 1988.[149][150][151] Dubbed the "dB Spectrum+", it performed well in the Indian market, selling over 50,000 units and achieving an 80% market share.[152]

Unofficial clones

Numerous unofficial Spectrum clones were produced, especially in the Eastern and Central European countries (e.g. in USSR (called Russian: Байт, Ленинград, Балтика), Romania, and Czechoslovakia) where several models were produced (such as the Tim-S, HC85, HC91, Cobra, Junior, CIP, CIP 3, Jet, Didaktik Gama), some featuring CP/M and a 5.25"/3.5" floppy disk.

There were also clones produced in South America (e.g. Microdigital TK90X and TK95, made in Brazil and the Czerweny CZ, made in Argentina). In the Soviet Union, ZX Spectrum clones were assembled by thousands of small start-ups and distributed through poster ads and street stalls. Over 50 such clone models existed.[153] Some of them are still being produced, such as the Pentagon and ATM Turbo.

In the UK, Spectrum peripheral vendor Miles Gordon Technology (MGT) released the SAM Coupé as a potential successor with some Spectrum compatibility. By this point, the Amiga and Atari ST had taken hold of the market, leaving MGT in eventual receivership.[154]

Recreations

In 2013, an FPGA-based redesign of the original ZX Spectrum known as the ZX Uno, was formally announced. All of its hardware, firmware and software are open source,[155] released as Creative Commons licence Share-alike. The use of a Spartan FPGA allows the system to not only re-implement the ZX Spectrum, but many other 8 bit computers and games consoles[156] The device can also run modern open FPGA machines such as the Chloe 280SE.[157] The Uno was successfully crowdfunded in 2016 and the first boards went on sale during the same year.[158]

In January 2014, Elite Systems, who produced a successful range of software for the original ZX Spectrum in the 1980s, announced plans for a Spectrum-themed bluetooth keyboard that would attach to mobile devices.[159][160] The company used a crowdfunding campaign to fund the Recreated ZX Spectrum, which would be compatible with games the company had already released on iTunes and Google Play.[161] Elite Systems took down its Spectrum Collection application the following month, due to complaints from authors of the original software that they had not been paid for the content.[162] Wired UK described the finished device, which was styled as an original Spectrum 48k keyboard, as "absolutely gorgeous" but said it was ultimately more of an expensive novelty than an actual Spectrum.[163] In July 2019, Eurogamer reported that many of the orders had yet to be delivered due to a dispute between Elite Systems and their manufacturer, Eurotech.[164]

Later in 2014, the Sinclair ZX Spectrum Vega retro video game console was announced by Retro Computers Ltd and crowdfunded on Indiegogo with the backing of Clive Sinclair.[165] The Vega, released in 2015, took the form of a handheld TV game[165][166] but the lack of a full keyboard[46] led to criticism from reviewers due to the large number of text adventures supplied with the device.[167][168] Most reviewers branded the device cheap and uncomfortable to use.[169][163]

The follow-up, the ZX Spectrum Vega+ was designed as a handheld game console. Despite reaching its crowdfunding target in March 2016,[170] the company failed to fulfil the majority of orders. On 30 July 2018, Eurogamer reported that one backer had received a ZX Vega+ console and quoted them as being "quite disappointed" that "the few supplied sample games don't work" and that the "build quality's not the greatest".[171] Reviewing the Vega+, The Register criticised numerous aspects and features of the machine, including its design and build quality and summed up by saying that the "entire feel is plasticky and inconsequential".[172] Retro Computers Ltd was wound up on 1 February 2019.[173]

The ZX Spectrum Next is an expanded and updated version of the ZX Spectrum computer implemented with FPGA technology[174] funded by a Kickstarter campaign in April 2017,[175] with the board-only computer delivered to backers later that year.[176] The finished machine, including a case designed[177] by Rick Dickinson who died during the development of the project, was released to backers in February 2020.[178] MagPi called it "a lovely piece of kit", noting that it is "well-designed and well-built: authentic to the original, and with technology that nods to the past while remaining functional and relevant in the modern age".[179] PC Pro magazine called the Next "undeniably impressive" while noting that the printed manual lacked an index, and that some features are "not quite ready".[180] A further Kickstarter for an improved revision of the hardware was funded in August 2020.[181]

Peripherals

Several peripherals were developed and marketed by Sinclair. The ZX Printer, a small spark printer, was already on the market upon the ZX Spectrum's release,[182] as its computer bus was partially backwards-compatible with that of its predecessor, the ZX81. It uses two electrically charged styli to burn away the surface of aluminium-coated paper to reveal the black underlay.[183]

The ZX Interface 1 add-on module includes 8 KB of ROM, an RS-232 serial port, a proprietary LAN interface known as ZX Net, and a port for connecting up to eight ZX Microdrives – tape-loop cartridge storage devices released in July 1983, known for their speed, albeit with some reliability concerns.[184][185] A revised version of these Microdrives was used on the Sinclair QL, although the storage format was electrically compatible but logically incompatible with the ZX Spectrum's. Sinclair Research also introduced the ZX Interface 2, which added two joystick ports and a ROM cartridge port.[186] Although the ZX Microdrives were initially greeted with good reviews,[187] they never became a popular distribution method due to fears over cartridge quality and piracy.[188]

A plethora of third-party hardware add-ons were available throughout the machine's life. Some notable ones included the Kempston joystick interface,[189] the Morex Peripherals Centronics/RS-232 interface, the Currah Microspeech unit for speech synthesis,[190] Videoface Digitiser,[191] RAM pack, the Cheetah Marketing SpecDrum, which was a drum machine,[192] and the Multiface, a snapshot and disassembly tool from Romantic Robot.[193] After the original ZX Spectrum's keyboard received criticism for its "dead flesh" feel,[3] external keyboards became especially popular.[194]

There were also many disk drive interfaces like the Abbeydale Designers/Watford Electronics SPDOS, Abbeydale Designers/Kempston KDOS, and Opus Discovery. The SPDOS and KDOS interfaces were bundled with office productivity software, including the Tasword Word Processor, Masterfile database, and Omnicalc spreadsheet. This bundle, along with OCP's Stock Control, Finance, and Payroll systems, introduced small businesses to streamlined computerised operations. In 1987 and 1988, Miles Gordon Technology released the DISCiPLE and +D systems, which became the most popular floppy disk systems in Western Europe. These systems had the capability to store memory images as disk snapshots, allowing users to restore the Spectrum to its exact previous state. Both systems were compatible with the Microdrive command syntax, simplifying the porting of existing software.[195]

During the mid-1980s, Telemap Group Ltd launched a fee-based service that allowed ZX Spectrum users to connect their machines to the Micronet 800 viewdata service via a Prism Micro Products VTX5000 modem. Micronet 800, hosted by Prestel, provided news and information about microcomputers and offered a form of instant messaging and online shopping.[196]

In 1983, DK'Tronics launched a Light Pen.[197]

Software

Most Spectrum software was originally distributed on audio cassette tapes, intended to work with a normal domestic cassette recorder.[26][198] Software was mainly distributed through print media such as magazines and books.[2][199][200] To load software onto the machine, the reader would type the BASIC program listing by hand, run it, and save it to the cassette for later use. Some magazines distributed 7" 331⁄3 rpm flexi disc records, or "Floppy ROMs", a variant of regular vinyl records which could be played on a standard record player.[201] Some radio stations would broadcast audio stream data via frequency modulation or medium wave so that listeners could directly record it onto an audio cassette themselves. ZX Spectrum-focused radio programmes existed in the United Kingdom, which were received over long distances on domestic radio receivers.[202]

Different types of software released for the machine include programming language implementations, databases,[203], word processors (Tasword being the most prominent[204]), spreadsheets,[203], drawing and painting tools (e.g. OCP Art Studio[205]), 3D-modelling (e.g. VU-3D[206][207]) and archaeology software.[208]

Video games comprised the vast majority of commercial ZX Spectrum software: hardware limitations of the machine required a particular level of creativity from video game designers.[209][210]

From August 1982 the ZX Spectrum came bundled with Horizons: Software Starter Pack,[211] a software compilation which included ten demonstration programs.[212]

According to the 90th issue of GamesMaster, the ten best games released were (in descending order) Head Over Heels, Jet Set Willy, Skool Daze, Renegade, R-Type, Knight Lore, Dizzy, The Hobbit, The Way of the Exploding Fist, and Match Day II.[213]

Some ZX Spectrum games hold a number of industry-firsts and Guinness World Records. These include Ant Attack (1981), the first home computer game to use isometric graphics,[214] Turbo Esprit (1986), the first open world racing game,[215] and Redhawk (1986), which featured the first superhero created specifically for a video game.[216] The last full price commercial game to be released for the ZX Spectrum was Alternative Software's Dalek Attack, which was released in July 1993.[217]

Community

The ZX Spectrum enjoyed a very strong community early on. Several commercially published print magazines were dedicated to covering the home computer family and its offshoots including Sinclair User (1982), Your Spectrum (1983) – rebranded as Your Sinclair in 1986, and CRASH (1984). In the early years, the magazines were focused on programming for the system, and carried many articles containing type-in programs and machine code tutorials. Later on they became almost completely game-oriented, starting many of the writing-styles, trends and tropes found in later video-game publications and reviews.

Several other contemporary computer magazines covered the ZX Spectrum as part of their regular coverage of the home computer industry at that time. These included Computer Gamer, Computer and Video Games, Computing Today, Popular Computing Weekly, Your Computer and The Games Machine.[218]

The Spectrum is affectionately known as the Speccy by elements of its fan following.[219]

More than 80 electronic magazines existed, many in Russian. Most notable of them were AlchNews (UK), Enigma Tape Magazine (UK), 16/48 (UK), ZX-Format (Russia), Adventurer (Russia), Microhobby (Spain) and Spectrofon (Russia). These frequently included games, demos, and utilities alongside the magazine content (much like a covertape on a paper magazine).

Reception

Initial reception of the ZX Spectrum was generally positive. Critics in Britain welcomed the new machine as a worthy successor to the ZX81; Robin Bradbeer of Sinclair User praised the additional keyboard functions the Spectrum had to offer, and lauded the "strength" of its ergonomic and presentable design.[220] Tim Hartnell from Your Computer noted that Sinclair had improved on the shortcomings of the ZX80 and ZX81 by revamping the Spectrum's load and save functions, noting that it made working with the machine "a pleasure".[221] Hartnell concluded that despite minor faults, the machine was "way ahead" of its competitors, and the quality far exceeded that of the BBC Micro.[222]

Computer and Video Games' Terry Pratt compared the Spectrum's keyboard negatively to the typewriter-style used on the BBC Micro, opining that it was an improvement over the ZX81 but unsuited for "typists".[223] Likewise, Gregg Williams from BYTE criticised the keyboard, declaring that despite the machine's attractive price the layout "is impossible to justice" and "poorly designed" in several respects. Williams was sceptical of the computer's appeal to American consumers if sold for US$220—"hardly competitive with comparable low-cost American units"—and expected that Timex would sell it for $125–150.[224] A more negative review came from Jim Lennox of Technology Week, who wrote that "after using it[...] I find Sinclair's claim that it is the most powerful computer under £500 unsustainable. Compared to more powerful machines, it is slow, its colour graphics are disappointing, its BASIC limited and its keyboard confusing".[69]

Legacy

The importance of the ZX Spectrum and its role in the early history of personal computing and video gaming has left many to regard it as the most influential computer of the 1980s.[3]

A number of notable games developers began their careers on the ZX Spectrum. Tim and Chris Stamper founded Ultimate Play the Game in 1982,[225] who found success with their blockbuster hits Jetpac (1983), Atic Atac (1983), Sabre Wulf (1984), and Knight Lore (1984).[226] The Stamper brothers later founded Rare, which became Nintendo's first Western third-party developer.[227] David Perry, the founder of Shiny Entertainment, moved from Northern Ireland to England to focus on developing games for the ZX Spectrum.[228]

Other prominent games developers include Julian Gollop (Chaos, Rebelstar, X-COM series), Matthew Smith (Manic Miner, Jet Set Willy), Jon Ritman (Match Day, Head Over Heels), Jonathan "Joffa" Smith (Batman: The Caped Crusader, Mikie, Hyper Sports), The Oliver Twins (the Dizzy series), Clive Townsend (Saboteur), Sandy White (Ant Attack; I, of the Mask), Pete Cooke (Tau Ceti), Mike Singleton (The Lords of Midnight, War in Middle Earth), and Alan Cox.[229] Although the 48K Spectrum's audio hardware was not as capable as chips in other popular 8-bit home computers of the era, computer musicians David Whittaker and Tim Follin produced notable multi-channel music for it.

The ZX Spectrum has been referenced numerous times in popular culture. On 23 April 2012, a Google doodle honoured the 30th anniversary of the Spectrum. As it coincided with St George's Day, the Google logo was of St George fighting a dragon in the style of a Spectrum loading screen.[230] One of the alternate endings in the interactive film Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018) included the main character playing data tape audio that, when loaded into a ZX Spectrum software emulator, generates a QR code leading to a website with a playable version of the "Nohzdyve" game featured in the film.[231]

"You cannot exaggerate Sir Clive Sinclair’s influence on the world [...] All your UK video game companies today were built on the shoulders of giants who made games for the ZX Spectrum."

— Television presenter Dominik Diamond on Sinclair's death in 2021.[232]

Some programmers have continued to code for the platform by using emulators on PCs.[233] A robust homebrew community continues into the present day, with several games being released commercially from new software houses such as Cronosoft.[234]

Since 2020, there has been a museum, LOAD ZX Spectrum, dedicated to the ZX Spectrum and other Sinclair products, located in Cantanhede, Portugal.[235]

See also

References

- Lewis, Rhys (23 April 2016). "April 23, 1982: ZX Spectrum brings affordable - and colourful - computing into Britain's homes". London: British Telecom. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Leigh 2018, p. 69.

- "How the Spectrum began a revolution". BBC. 23 April 2007. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Mott 2000, p. 76.

- Owen, Chris. "ZX Spectrum 16K/48K". Planet Sinclair. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- Williams, Chris (23 April 2007). "Sinclair ZX Spectrum: 25 today". Register Hardware. Situation Publishing. Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- Cellan-Jones, Rory (23 April 2012). "The Spectrum, the Pi - and the coding backlash". BBC News. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- Mason, Graeme (18 February 2022). "ZX Spectrum at 40: a look back". NME. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- Oliver, Phillip (26 October 2017). "ZX Spectrum: An enduring legacy". GamesIndustry.biz. Brighton: Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- Dale 1985, p. 21.

- Bailey, Elizabeth (12 April 1981). "INVENTOR; TRYING AGAIN IN CONSUMER ELECTRONICS". New York City: The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- Owen, Chris. "Planet Sinclair: The Black Watch". Planet Sinclair. Archived from the original on 31 August 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- Kean 1985b, p. 126.

- Dale 1985, pp. 77–78.

- "Sir Clive Sinclair obituary". London: The Times. 1 October 2023. Archived from the original on 10 November 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Dale 1985, p. 89.

- Dale 1985, p. 91.

- Laurie 1981, p. 113.

- Hayes 1981, p. 119.

- Lorenz 1982, p. 18.

- "Sinclair ZX8". Sinclair Research. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- Clarke 1982, p. 390.

- Engineering Today 1982, pp. 20–23.

- Hayman, Martin (June 1982). "Interview – Clive Sinclair". Practical Computing. pp. 54–64.

- Brown, Nathan (23 April 2012). "The making of the ZX Spectrum". Edge. Bath: Future plc. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Leigh 2018, p. 68.

- Speed, Richard (22 April 2022). "Sinclair's 8-bit home computer, ZX Spectrum, turns 40". The Register. London: Situation Publishing. Archived from the original on 26 May 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- Adams 1982, p. 14.

- Gore 1982, p. 38.

- Gore 1982, pp. 38–39.

- Adamson & Kennedy 1986, pp. 84–85.

- Smith, Tony (23 April 2012). "Happy 30th Birthday, Sinclair ZX Spectrum". The Register. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- Kelion, Leo (19 April 2012). "ZX Spectrum's chief designers reunited 30 years on". BBC News. London: BBC. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- "Sinclair Spectrum designer Rick Dickinson dies in US". BBC News. London: BBC. 26 April 2018. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023.

- "Alpia drawing board - Science Museum Group Collection". London: The Science Museum Group. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

- Day, Peter (9 September 2014). "How Dundee became a computer games centre". BBC News. London. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- "ZX Spectrum Computer and associated game cassettes". The McManus. Dundee: Dundee Art Gallery. 20 January 2012. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- Adamson & Kennedy 1986, p. 94.

- Warman, Matt (23 April 2012). "ZX Spectrum at 30: the computer that started a revolution". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

It was the computer that introduced a generation to video gaming, helped to earn Sir Clive Sinclair a knighthood and even made programming cool: the ZX Spectrum has a lot to answer for.

- "ZX Spectrum profile". Retro Gamer. Bath: Future plc. 4 December 2013. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- Adams 1982, p. 52.

- Clark 1982, p. 4.

- Clark 1982, p. 14.

- Kean 1985b, p. 127.

- "Sir Clive Sinclair, inventor of an early pocket calculator who transformed the home-computing market but came unstuck with the infamous C5 – obituary". London: The Telegraph. 16 September 2021. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- Kelion, Leo (2 December 2014). "Syntax era: Sir Clive Sinclair's ZX Spectrum revolution". BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 December 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- Clark 1982, p. 43.

- Clark 1982, p. 44.

- Johnston 1982, p. 4.

- Pratt 1982a, p. 4.

- Leigh 2018, p. 70.

- Adamson & Kennedy 1986, p. 257.

- "Spectrum sales top 200,000". Popular Computing Weekly. No. 7. Sunshine Publications. 17 February 1983. p. 1. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- "Spectrums 'to double'". Home Computing Weekly. No. 10. Argus Specialist Publications. 10 May 1983. p. 14. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- "Spectrum tops ½ million mark". Popular Computing Weekly. No. 31. Sunshine Publications. 4 August 1983. p. 1. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- "1m Spectrums". Popular Computing Weekly. No. 51. Sunshine Publications. 22 December 1983. p. 5. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- Advertisement (December 1983). "Now from Timex...a powerful new computer". BYTE. p. 281. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Bradbeer 1983, p. 83.

- Adamson & Kennedy 1986, p. 143.

- Segre 1983, p. 18.

- Adamson & Kennedy 1986, p. 98.

- Adamson & Kennedy 1986, p. 97.

- Adamson & Kennedy 1986, p. 114.

- "Sir Clive Sinclair: Tireless inventor ahead of his time". BBC News. London. 16 September 2021. Archived from the original on 18 May 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- Goodenough, Jan (March 2000). "Biography of Sir Clive Sinclair". British Mensa. Archived from the original on 2 February 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- Bates, Stephen (17 September 2021). "Sir Clive Sinclair obituary". London: The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- Leigh 2018, p. 104.

- Oxford, Nadia (18 January 2012). "Ten Facts about the Great Video Game Crash of '83". IGN. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Leigh, Peter (21 April 2017). "ZX Spectrum Story: Celebrating 35 Years of the Speccy". Nostalgia Nerd. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- "Market size and market shares". Video Games: A Report on the Supply of Video Games in the UK. United Kingdom: Monopolies and Mergers Commission (MMC), His Majesty's Stationery Office. April 1995. pp. 66 to 68. ISBN 978-0-10-127812-6.

- Baker, Chris (6 August 2010). "Sinclair ZX80 and the Dawn of 'Surreal' U.K. Game Industry". Wired. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Mardsen, Rhordi (25 January 2015). "Geeks Who Rocked The World: Documentary Looks Back At Origins Of The Computer-games Industry". The Independent. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- Hayman 1982, p. 23.

- "Hollis pulls out of Sinclair offer". The New York Times. New York City. 10 August 1985. p. 32. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- Bourne 1985a, p. 7.

- "The 80s home computer boom (video)". BBC Radio 4. London: BBC. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- Denham, Sue (March 1984). "Sir Clive Makes The Quantum Leap". Your Spectrum. No. 2. Retrieved 19 April 2006.

- "QL News / SinclairWatch". Your Spectrum. No. 5. July 1984. Retrieved 15 December 2006.

- Roger Munford (September 1984). "Circe". Your Spectrum. No. 7. Retrieved 15 December 2006.

- "Timex/Sinclair history". ZQAOnline. Archived from the original on 17 July 2006. Retrieved 15 December 2006.

- "QL, what? Never heard of the QL..." Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- "Kept in the Dark". CRASH. No. 22. November 1985. Retrieved 15 December 2006.

- "Sinclair ZX Spectrum 128". The Center for Computing History. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- Dale 1985, p. 151.

- Fraser, John (9 April 1986). "The rise and fall of a British electronics wizard". The Globe and Mail. Toronto, Canada.

- "C5 advert claims rejected". The Times. London: News Corp. 17 July 1985. p. 3.

- "Sinclair to Sell British Unit". The New York Times. The Associated Press. 18 June 1985. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- Kidd 1986, p. 7.

- Scolding 1986, p. 7.

- Phillips 1986, p. 47.

- Feder, Barnaby (19 May 1985). "Inventing the Future". The New York Times. New York City. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- Vickers, Steven (1982). "Introduction". Sinclair ZX Spectrum BASIC Programming. Sinclair Research Ltd. Archived from the original on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2006.

- Vickers, Steven (1982). "Colours". Sinclair ZX Spectrum BASIC Programming. Sinclair Research Ltd. Archived from the original on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2006.

- EP patent 0107687, Richard Francis Altwasser, "Display for a computer", issued 6 July 1988, assigned to Sinclair Research Ltd

- "Face off – ZX Spectrum vs Commodore 64". Eurogamer. Bath: Future plc. 29 April 2012. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- Wilkins 2015b, p. 16.

- "PortFE". 16K / 48K ZX Spectrum Reference.

- Vickers, Steven. "BEEP". Sinclair ZX Spectrum BASIC Programming. Sinclair Research Ltd. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014.

- Nash 1984, p. 217.

- Vickers, Steven (1982). "Basic programming concepts". Sinclair ZX Spectrum BASIC Programming. Sinclair Research Ltd. Archived from the original on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 19 September 2006.

- "Tape Data Storage". Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- "Chapter 20 - Tape Storage". Basic Programming. Sinclair Research. 1982.

- Stratford, Christopher (11 May 2014). "The Home Computers Hall of Fame, The Machines". gondolin.org.uk. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "The High Street Spectrum". ZX Computing: 43. February 1983. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- Gilbert 1983a, p. 13.

- Goodwin, Simon (September 1984). "Suddenly, it's the 64K Spectrum!". Your Spectrum (7): 33–34. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

So the first three issues of the Spectrum used a combination of eight 16K chips and eight 32K ones. The latest machines depart from that combination, but Sinclair Research has been very quiet about the alteration.

- Owen, Chris (6 September 2003). "Spectrum 48K Versions". Planet Sinclair. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

It is often possible to determine which version of the Spectrum 16/48K one has without opening the case, as there are a number of clues...

- THORN (EMI) DATATECH LTD (March 1984). Servicing Manual For ZX Spectrum (PDF). Sinclair Research Ltd. p. 4.3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "ZX Spectrum Models". Spectrum for Everyone. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- "Spectrum For Everyone Serial DB". Spectrum For Everyone Serial DB. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- Wilkins 2015a, p. 16.

- Wilkins 2015a, p. 17.

- "Sinclair Recall Notice". Popular Computing Weekly. No. 9. Sunshine Publications. 3 March 1983. p. 6. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- "Big response to call-back". Home Computing Weekly. No. 2. Argus Specialist Publications. 15 March 1985. p. 5. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- "Spectrum power supplies – How we discovered the danger". Home Computing Weekly. No. 3. Argus Specialist Publications. 22 March 1985. p. 7. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- Denham, Sue (December 1984). "The Secret That Was Spectrum+". Your Spectrum (10): 104. Archived from the original on 6 May 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- "Spectrum surprise!". Home Computing Weekly. No. 85. Argus Specialist Publications. 23 October 1984. p. 1. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- Owen, Chris. "ZX Spectrum+". Planet Sinclair. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- "News: New Spectrum launch". Sinclair User (33): 11. December 1984. Archived from the original on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 19 August 2006.

- Frey 1985, p. 5.

- Bourne 1985b, p. 5.

- Frey 1986, p. 11.

- (in Spanish) Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda (BOE 211 de 3 September 1985), Real Decreto 1558/1985, de 28 de agosto, por el que se aclara el alcance del mínimo específico introducido en la subpartida 84.53.B.II del Arancel de Aduanas, por el Real Decreto 1215/1985 Archived 30 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Rango: Real Decreto, Páginas: 27743 – 27744, Referencia: 1985/18847.

- (in Spanish) Ministerio de Industria y Energía (BOE 179 de 27 July 1985), Real Decreto 1250/1985, de 19 de junio, por el que se establece la sujeción a especificaciones técnicas de los terminales de pantalla con teclado, periféricos para entrada y representación de información en equipo de proceso de datos Archived 30 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Rango: Real Decreto, Páginas: 23840–23841, Referencia: 1985/15611.

- "Murata 5v Switching Regulator (for Toastrack models)". Retro Revival Shop. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- "Clive discovers games – at last". Sinclair User (49): 53. April 1985. Archived from the original on 24 September 2006.

- "Spectrum 128+3 Manual, Chapter 8 Part 24". Amstrad. Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- "Spectrum 128+3 Manual, Chapter 7". Amstrad. Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- "World of Spectrum – Documentation – ZX Spectrum 128 Manual Page 9". Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- Goodwin, Simon (December 1987). "Tech Tips – Amstrology". Crash (48): 143.

- DataServe Retro. "Spectrum +2, +2A, and +2B Spares". Archived from the original on 15 February 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- South, Phil (July 1987). "It's here... the Spectrum +3". Your Sinclair (17): 22–23. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- Amstrad (November 1987). "The new Sinclair has one big disk advantage". Sinclair User (68): 2–3. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- Goodwin, Simon (December 1987). "Tech Tips – +3 Faults". Crash (48): 145.

- "Power supply for Spectrum 128, +2A, +3". York Distribution Limited. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- "Amstrad Kills Plus 3". Crash. No. 82. Newsfield. November 1990. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- "Death Of The +3". Your Sinclair. No. 60. Future Publishing. December 1990. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- "Dishy New Spectrum in Sex Scandal". Crash. No. 26. Newsfield. 26 January 1989. p. 9. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- "Amstrad again". New Computer Express. No. 5. Future Publishing. 10 December 1988. p. 55. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- Spectrum +3 Service Manual. AMSTRAD. p.18.

- "Image of Spectrum +2A power supply". Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- Spectrum +2B/+3B Service Manual. AMSTRAD.

- "Spex – Sounding Out". New Computer Express. No. 44. Future Publishing. 9 September 1989. p. 54. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- Goodwin, Simon (April 1987). "SINCLAIR'S Z88 – Pandora's Box?". Crash (39). Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM – Timex Computer 2048". Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- Prata 1987, p. 1.

- Prata 1987, pp. 2–3.

- "Deci Bells Electronics Limited Information - Deci Bells Electronics Limited Company Profile, Deci Bells Electronics Limited News on The Economic Times". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- "deciBells dB Spectrum+ – Sinclair Collection".

- "dB Spectrum+ at Spectrum Computing - Sinclair ZX Spectrum games, software and hardware". Spectrum Computing. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- "The innovative legacy of Clive Sinclair". The Week. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- "Tirlochan Singh". isourcingindia. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- Owen, Chris. "Clones and variants". Planet Sinclair. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- Alway, Robin. "So what really has happened to the SAM Coupé?". Your Sinclair (56): 40. Archived from the original on 15 March 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- By (13 January 2017). "Retro ZX Spectrum Lives A Spartan Existence". Hackaday. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- "Back this Crowdfunding "ZX-UNO" in Verkami". www.verkami.com. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Old, Vintage is The New (4 February 2020). "Introducing the Chloe 280SE, a new Z80 microcomputer". Vintage is the New Old, Retro Games News, Retro Gaming, Retro Computing. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- "ZX-Uno". Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- Sharwood, Simon (29 January 2014). "Sinclair's ZX Spectrum to LIVE AGAIN!". The Register. Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- Hamilton, Alex (2 January 2014). "ZX Spectrum is coming back as a Bluetooth keyboard". TechRadar. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- Curtis, Sophie (2 January 2014). "ZX Spectrum to be resurrected as Bluetooth keyboard". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- Alex Hern. "ZX Spectrum Kickstarter project stalls over unpaid developer bills". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Rundle, Michael (1 October 2015). "Which of the 'retro' Spectrum remakes is worth your £100?". Wired UK. New York City: Condé Nast. ISSN 1357-0978. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Yin-Poole, Wesley (8 July 2016). "When Kickstarters go bad: chasing down the Recreated ZX Spectrum". Eurogamer. Bath: Future plc. Archived from the original on 11 October 2023. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Samuel Gibbs (2 December 2014). "ZX Spectrum gets new lease of life as Vega games console". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Theo Merz (3 January 2014). "8 reasons you should be excited about the return of the ZX Spectrum". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- McFerran, Damien. "ZX Spectrum Vega Review". Trusted Reviews. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- "Sinclair Vega". www.thespectrumshow.co.uk. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- "ZX Spectrum Vega vs Recreated ZX Spectrum". Stuff. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Merriman, Chris. "ZX Spectrum Vega+ raises three times its Indiegogo target in three weeks". The Inquirer. Incisive Business Media Limited. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Wales, Matt (30 July 2018). "Backers have finally started to receive the beleaguered ZX Spectrum Vega Plus". Eurogamer.net. Gamer Network. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- Corfield, Gareth (9 August 2018). "ZX Spectrum Vega+ blows a FUSE: It runs open-source emulator". The Register.

- Corfield, Gareth (5 February 2019). "Is this a wind-up?". The Register. Situation Publishing. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- "About". Sinclair ZX Spectrum Next. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "Celebrate the Sinclair ZX Spectrum's 35th anniversary with… yet another retro console". Metro (UK). 24 April 2017.