Wu Peifu

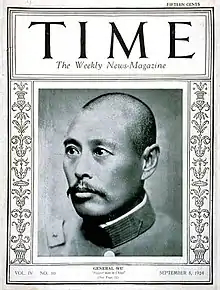

Wu Peifu[1] or Wu P'ei-fu[2] (Chinese: 吳佩孚; April 22, 1874 – December 4, 1939) was a major figure in the struggles between the warlords who dominated Republican China from 1916 to 1927.

Wu Peifu 吳佩孚 | |

|---|---|

Gen. Wu Peifu | |

| Nickname(s) | "Jade Marshal" (玉帥) |

| Born | April 22, 1874 Penglai, Shandong, Qing Empire |

| Died | December 4, 1939 (aged 65) Beiping, Republic of China (Japanese occupied Zone) |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1898–1927 |

| Rank | Marshal |

| Commands held | 3rd Division, Beiyang Army |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

|

| Wu Peifu | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 吳佩孚 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 吴佩孚 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Early career

Born in Shandong Province in eastern China, Wu initially received a traditional Chinese education. He later joined the Baoding Military Academy (保定軍校) in Beijing and embarked on a career as a professional soldier. His talents as an officer were recognized by his superiors, and he rose quickly in the ranks.

Wu joined the "New Army" (新軍) (renamed the Beiyang Army in 1902) created by modernizing Qing dynasty Gen. Yuan Shikai. Following the fall of the Qing in 1911, and after Yuan's rise to President of the Republic of China and his subsequent disastrous attempt to proclaim himself emperor, political power in China quickly devolved into the hands of various regional military authorities, inaugurating the era of warlordism. In 1915 Wu became commander of the 6th Brigade.

Zhili Clique

After Yuan's death in 1916, his Beiyang Army split into several mutually hostile factions that battled for supremacy over the following years. The major factions included Duan Qirui's Anhui clique, Zhang Zuolin's Fengtian clique, and Feng Guozhang's Zhili clique, of which Wu Peifu was a member. Duan Qirui's faction dominated politics in Beijing from 1916 to 1920 but was forced to maintain an uneasy relationship with Feng Guozhang's faction to maintain stability. The two clashed over methods of dealing with the restive south, with Duan pushing for military conquest and Feng preferring negotiation.

Feng died in 1919 and the leadership of the Zhili Clique was secured by Cao Kun with the support of Wu Peifu and Sun Chuanfang. Cao and Wu began to agitate against Duan and the Anhui clique and issued circular telegrams denouncing his collaboration with Japan. When they successfully pressured the president to dismiss Duan's key subordinate Gen. Xu Shuzheng, Duan began to prepare for war against the Zhili Clique. At this juncture, Cao Kun and Wu Peifu began to organize a wide-reaching alliance including all opponents of the Anhui clique. In November 1919 Wu Peifu met with representatives of Tang Jiyao and Lu Rongting (warlords of Yunnan and Guangxi, respectively) at Hengyang and signed a treaty titled “Rough Draft of the National Salvation Allied Army” (救国同盟军草约), forming the base of the anti-Anhui clique alliance that also included Zhang Zuolin's powerful Fengtian clique.

Zhili-Anhui War

When hostilities finally broke out in July 1920, Wu Peifu took a prominent role as commander-in-chief of the anti-Anhui army. At first things did not go well for Zhili forces, as they were pushed back by Anhui troops across the front. However, Wu decided to execute a daring maneuver on the western end of the front by first outflanking enemy positions and then directly assaulting the enemy's headquarters position. The gambit paid off and Wu was rewarded with an astounding victory and the capture of many of the officers in the enemy command. The Anhui army crumbled within a week and Duan Qirui fled to the Japanese settlement at Tianjin. Wu Peifu was credited as the strategist behind the unexpectedly swift victory.

In the aftermath of the conflict, the Zhili and Fengtian cliques agreed to a power-sharing coalition government. However, Zhang Zuolin, leader of the Fengtian clique, became increasingly uneasy with Wu Peifu's vehement anti-Japanese stance that threatened to upset the delicate arrangement Zhang had reached with the Japanese in his power base of Manchuria. Wu and Zhang also clashed over who would occupy the position of premier, replacing each other's choices with their own. Soon the coalition between Zhili and Fengtian broke down and hostilities were inevitable.

First Zhili–Fengtian War

In this war Wu Peifu was again placed in the position of commander-in-chief of Zhili forces. Fighting would take place on a broad front south of Beijing and Tianjin and lasted from April to June 1922. Initially, the Zhili army again suffered several setbacks against the well-equipped Fengtian army. Yet once again, Wu Peifu's leadership and planning turned the tide in favor of the Zhili clique. He executed several outflanking maneuvers that forced the western front of the Fengtian army back towards Beijing, then he lured it into a trap by feigning retreat. The result was the annihilation of the western wing of the Fengtian army, making its more successful eastern operations untenable. Zhang Zuolin was forced to order a general retreat towards Shanhaiguan, thereby ceding control of the capital to Wu and the Zhili clique.

Victorious, Cao Kun and Wu Peifu's Zhili clique nevertheless took control of a government whose control over the provinces had greatly deteriorated. Manchuria was now de facto independent under Zhang Zuolin and the still formidable Fengtian clique, while the south was divided among myriad warlord armies, including remnants of the Anhui clique and Sun Yat-sen's Kuomintang.

Control of the Beijing Government

The new government in Beijing was supported by Great Britain and the United States. Li Yuanhong, the last president with any legitimacy, was recalled to sit as president again on June 12, 1922; however, any cabinet member had to be cleared by Wu Peifu. By this time Wu's prestige and fame had far surpassed that of his former mentor Cao Kun, nominally head of the Zhili clique. This strained their relationship, although it did not result in a fracture of the Zhili clique. Wu tried to restrain Cao when the latter began political machinations for the presidency but ultimately could not prevent Cao from toppling the cabinet and impeaching Li. Cao then spent several months campaigning for the presidency and even openly declared he would pay $5000 to any parliamentarian who would cast a vote for him. This caused national condemnation against the Zhili clique but did not prevent Cao from being elected in October 1923.

In 1923 Wu ruthlessly broke a strike at the important Hankou–Beijing railway by sending in troops to violently suppress the workers and their leaders. The soldiers killed 35 workers and injured many more. Wu's reputation with the Chinese people suffered significantly because of this event, though he gained the favor of British and American business interests operating in China.

Although it appeared that Zhili's power was secure for the time being, a crisis in the south soon precipitated another showdown with the Fengtian clique. The crisis was over the city of Shanghai, the commercial powerhouse of the nation. It was part of the province of Jiangsu, under Zhili control, but actually administered by Zhejiang, ruled by the remnants of the Anhui clique. When the Zhili clique demanded the return of Shanghai to their administration they were refused and fighting soon broke out. Zhang Zuolin in Manchuria and Sun Yat-sen, then in Guangdong, quickly declared their support for the Anhui clique and geared up for war. Wu Peifu dispatched his subordinate and protégé Sun Chuanfang to the south to deal with the Anhui clique and any attack that may have come from Sun's Kuomintang forces, while Wu himself prepared to face off again with Zhang's Fengtian army.

Second Zhili–Fengtian War

Now called the "Jade Marshal" (玉帥) and generally acknowledged to be China's ablest strategist at the time, Wu Peifu was widely expected to win, and by doing so to finally put an end to various quasi-independent regional authorities. His warlord troops were some of the best trained and drilled in China, and as leader of the Zhili Clique, he almost continuously fought northern Chinese warlords like Zhang Zuolin. Known as the philosopher general due to having graduated from the imperial examinations,[3] he was said at the time to own the world's largest diamond.

Hundreds of thousands of men fought in this major battle between Zhang's Fengtian army and Wu's Zhili forces. At a key moment, one of Wu's chief allies, Feng Yuxiang, deserted the front, marched on Beijing and in the so-called Beijing Coup (Beijing zhengbian) overthrew the existing regime and proclaimed a new and mildly progressive government. Wu Peifu's military strategy was thrown into confusion by this catastrophe in his rear, and he was defeated by Zhang's forces near Tianjin. After the victory of the Fengtian clique, Duan Qirui was made the head of state and he proclaimed a provisional government.

Northern Expedition

Wu maintained a power base in Hubei and Henan in central China until he was confronted by the Kuomintang army during the Northern Expedition in 1927. With armies detained by Kuomintang allies in the Northwest, Wu was forced to withdraw to Zhengzhou in Henan.

As Wu Peifu's armies were being overrun by the Kuomintang forces of Chiang Kai-shek, during a breakfast interview with a westerner Wu Peifu was noticed carrying an old book; the interviewer asked him the title, and Wu replied, "The Military Campaigns of the Kingdom of Wu. They didn't have any machine guns or airplanes then." Wu never held a political office during his years as a warlord.[4]

Wu Peifu hung a portrait of George Washington in his office. He was a nationalist, and refused to enter foreign concessions—not even to hide from his enemies—because he viewed them as an affront to China, and instead chose a much more perilous method of escape.[5]

Later years

After the second Sino-Japanese War broke out, Wu refused to cooperate with the Japanese. In 1939, when the Japanese invited him to be the leader of the puppet government in North China, Wu made a speech saying that he was willing to become the leader of North China again on behalf of the New Order in Asia, if every Japanese soldier on China's soil gave up his post and went back to Japan. He then went back into retirement. In December 1939, Wu went to a dentist complaining of a toothache, and received an extraction. He died two weeks later, ostensibly of sepsis.

See also

References

Citations

- Karl E. Meyer; Shareen Blair Brysac (10 March 2015). The China Collectors: America's Century-Long Hunt for Asian Art Treasures. St. Martin's Press. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-1-137-27976-7.

- The China Monthly Review, Volume 38. Millard. September 1926.

- French, Paul (2007). Carl Crow, a Tough Old China Hand The Life, Times and Adventures of an American in Shanghai. Hong Kong University Press. p. 114. ISBN 9789622098022.

- John B. Powell (2008). My Twenty Five Years in China. Read. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-4437-2626-9. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Jonathan Fenby (2005). Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 103. ISBN 0-7867-1484-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

External links

![]() Quotations related to Wu Peifu at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Wu Peifu at Wikiquote