Yaghnobis

The Yaghnobi people (Yaghnobi: yaγnōbī́t or suγdī́t; Tajik: яғнобиҳо, yağnobiho/jaƣnoʙiho) are an East Iranian ethnic minority in Tajikistan. They inhabit Tajikistan's Sughd province in the valleys of the Yaghnob, Qul and Varzob rivers. The Yaghnobis are considered to be descendants of the Sogdian-speaking peoples[2] who once inhabited most of Central Asia beyond the Amu Darya River in what was ancient Sogdia.

yaγnōbī́t, яғнобиҳо | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| c. 25,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Valleys around Yaghnob, Qul and Varzob Rivers, Zafarobod District and elsewhere in Tajikistan | |

| Languages | |

| Yaghnobi, Tajik, Uzbek | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Iranian peoples Especially Ossetians and Wakhis |

They speak the Yaghnobi language, a living Eastern Iranian language (the other living members being Pashto, Ossetic and the Pamir languages). Yaghnobi is spoken in the upper valley of the Yaghnob River in the Zarafshan area of Tajikistan by the Yaghnobi people, and is also taught at schools.[3] It is considered to be a direct descendant of Sogdian and has often been called Neo-Sogdian in academic literature.[4]

The 1926 and 1939 census data gives the number of Yaghnobi language speakers as approximately 1,800. In 1955, M. Bogolyubov estimated the number of Yaghnobi native speakers as more than 2,000. In 1972, A. Khromov estimated 1,509 native speakers in the Yaghnob valley and about 900 elsewhere. The estimated number of Yaghnobi people is approximately 25,000.[1]

The Sogdian language is one of the Iranian languages, along with Bactrian language, Khotanese Saka, Persian language, Tajik language, Pashto language, the Kurdish languages and Parthian language.[5] It possesses a large historic literary corpus.[5]

History

Antiquity

Their traditional occupations were in agriculture, growing produce such as barley, wheat, and legumes as well as breeding cattle, oxen and asses. There were traditional handicrafts including weaving which was mostly done by the men. The women worked on moulding earthenware crockery.[6]

The Yaghnobi people originated from the Sogdians, a people dominant in the area until the Muslim conquests in the 8th century when Sogdiana was defeated. In that period Yaghnobis settled in the high valleys.

pre-20th century

The ancient Sogdians fled to the Yaghnob Valley to escape the medieval Arab Caliphate, and their direct descendants, the Yaghnobi, lived there in peaceful isolation until the 1820s.[7][8]

20th century

Until the 20th century the Yaghnobis lived through their natural economy and some still do, as the area they originally inhabited is still remote from roads and power transmission lines. The first contact with Soviet Union in the 1930s during the Great Purge, led to many Yaghnobis being exiled, but perhaps the most traumatic events were the forced resettlement in 1957 and 1970, from the Yaghnob mountains to the semi-desert lowlands of Tajikistan.[9][10]

In the 1970s, Red Army helicopters were sent to valleys to evacuate the population, ostensibly because Yaghnobi kishlaks (villages) were considered at risk from avalanches. Some Yaghnobis reportedly died of shock in helicopters as they were moved to the plains. Many were then forced to work at cotton plantations on the plains.[11][12] As a result of overwork and the change in environment and lifestyle, several hundred Yaghnobis died of disease.[13] While some Yaghnobis rebelled and returned to the mountains, the Soviet government demolished the empty villages and the largest village on the Yaghnob River, Piskon, was removed from official maps. Officials also destroyed Yaghnobi religious books, the oldest of which was 600 years old. Yaghnobi ethnicity was officially abolished by the Soviet government.

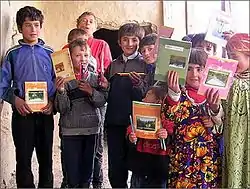

Since 1983, families have begun to return to the Yaghnob Valley. The majority of those that remain on the plains tend to be assimilated with the Tajiks,[14][15] as their children study in school in the Tajik language. The returnees live through the natural economy, and the majority remain without roads and electricity.

21st century

The Yaghnob Valley comprises approximately ten settlements, each housing between three and eight families.[8][16] There are other small settlements elsewhere.[8][16] The upper Yaghnob River Valley was protected by an until recently almost impenetrable gorge.[17] They also live in and about the Amu Darya River, the Yaghnob River, the Yaghnob Valley, the Qul River, the Varzob rivers and the town of Anzob.[16]

Religion

The Yaghnobi people are Sunni Muslims but a few also profess Isma'ilism.[18][19][20] Some elements of pre-Islamic religion (probably Zoroastrianism) are still preserved.[21]

Genetics

Y-DNA haplogroup R1 (R-M173), is found at a relatively high level of 48% among Yaghnobi males. However, detailed breakdowns of this result into subclades are unavailable. That means it is unclear if these examples of R1 are subclades common in Central Asia, Eastern Europe and South Asia, and associated with the Copper Age Kurgan Culture of the Eurasian Steppe and the spread of Iranian-speaking peoples, who entered the area circa 3000 BCE.[22]

The spread of agriculture from the Middle East during the Neolithic era is associated with Haplogroup J, which is found at 32%.[22]

Haplogroup L (M20), which is most common in modern north-west South Asian populations, is found at a rate of approximately 10%.[22]

Autosomally, Tajiks are very close to Yaghnobis, and very different from Persians, from whom they borrow their language.[23]

References

- "The Peoples of the Red Book – The Yaghnabis". Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- Paul Bergne (15 June 2007). The Birth of Tajikistan: National Identity and the Origins of the Republic. I.B.Tauris. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-1-84511-283-7.

- Inside the New Russia (1994): Yagnob

- electricpulp.com. "YAGHNOBI – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- "YAGHNOBI – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- (in Russian) Большая Советская Энциклопедия

- Jamolzoda, A. Journey to Sogdiana's Heirs www.yagnob.org

- "Discovery Central Asia: THE LOST WORLD OF THE YAGNOB". www.discovery-central-asia.com.

- (in Russian) Вокруг света – Страны – - Таджикистан – Последние из шестнадцатой сатрапии

- Loy, Thomas. "From the mountains to the lowlands – the Soviet policy of "inner-Tajik" resettlement". Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften. Retrieved 2006-08-06.

- Jamolzoda, Anvar (July–August 2006). "Journey to Sogdiana's Heirs" (PDF). yagnob. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-03-13.

- "Tajikistan: The Sons of Somoni Strive to Preserve Distinct Cultural Identity". EURASIANET.org. June 22, 2012.

- Loy, Thomas (July 18, 2005). "Yaghnob 1970 A Forced Migration in the Tajik SSR". Central Eurasia-L Archive. Archived from the original on 2006-09-01. Retrieved 2006-08-06.

- Paul, Daniel Paul; Abbess, Elisabeth; Müller, Katja; Tiessen, Calvin and; Tiessen, Gabriela (2009). "The Ethnolinguistic Vitality of Yaghnobi" (PDF). SIL Electronic Survey Report 2010-017, May 201. SIL International. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- Jenkins II, Mark D. (May 26 – September 8, 2014). "Being Yaghnobi: Expressions of Identity, Place, and Revitalization as a Minority in Tajikistan" (PDF) (Title VIII Final Report). Dushanbe, Tajikistan: American Councils Research Fellowships. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Ягноб – Древняя Согдиана: Прошлое, Настоящее и Будущее".

- Пагануцци, Н. В. (1968). Фанские горы и Ягноб (in Russian). Moscow: Fizkultura i sport.

- L'Oeil de la Photographie (April 5, 2014). "Karolina Samborska Tajik Kitchen stories". The Eye of Photography. Poland.

- Samborska, Karolina. "tajik kitchen stories". Karolina Samborska // Photographer.

- Akiner, Shirin (1986). Islamic Peoples of the Soviet Union. London: Routledge. p. 382. ISBN 0-7103-0188-X.

- According to http://www.pamirs.org Zoroastrian Designs on Embrodiary

- R. Spencer Wells et al., "The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (August 28, 2001).

- Yunusbayev, B.; Metspalu, M.; Metspalu, E.; Valeev, A.; Litvinov, S.; Valiev, R.; Akhmetova, V.; Balanovska, E.; Balanovsky, O.; Turdikulova, S.; Dalimova, D.; Nymadawa, P.; Bahmanimehr, A.; Sahakyan, H.; Tambets, K.; Fedorova, S.; Barashkov, N.; Khidiyatova, I.; Mihailov, E.; Khusainova, R.; Damba, L.; Derenko, M.; Malyarchuk, B.; Osipova, L.; Voevoda, M.; Yepiskoposyan, L.; Kivisild, T.; Khusnutdinova, E.; Villems, R. (21 April 2015). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia". PLOS Genetics. 11 (4): e1005068. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068.g002. PMC 4405460. PMID 25898006.

External links

- The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire

- Bielmeier, Roland (August 15, 2006). "YAGHNOBI". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- PAMIRI TAJIKS AND YAGHNOBIS

- On the Edge of the Snow - A Documentary (A Long Draft Trailer)