Yank Robinson

William H. "Yank" Robinson (September 19, 1859 – August 25, 1894) was an American professional baseball infielder. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) from 1884 to 1892 for the Detroit Wolverines, Baltimore Monumentals, St. Louis Browns, Pittsburgh Burghers, Cincinnati Kelly's Killers, and Washington Senators.

| Yank Robinson | |

|---|---|

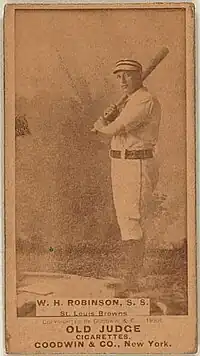

.tiff.png.webp) Robinson in 1888 | |

| Second baseman | |

| Born: September 19, 1859 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | |

| Died: August 25, 1894 (aged 34) St. Louis, Missouri | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| August 24, 1882, for the Detroit Wolverines | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| August 10, 1892, for the Washington Senators | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .241 |

| Hits | 825 |

| Runs batted in | 399 |

| Teams | |

Robinson was a starter for St. Louis Browns teams that won four consecutive American Association pennants and the 1886 World Series. While playing for the Browns, he set the major league record with 116 walks in 1888 and broke his own record with 118 walks in 1889. During his peak years from 1887 to 1890, Robinson drew 472 free passes (427 walks and 45 times hit by pitch) and 400 hits in 2,115 plate appearances, giving him a "free pass" percentage of .223 and an on-base percentage of .412. His Offensive WAR ratings of 3.8, 3.7 and 3.6 ranked sixth in the American Association in 1886 and 1887 and eighth in 1888.

Early years

Robinson was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1859.[1] He came from a poor background, left home at a young age and moved to Boston where he played sandlot baseball.[2]

Professional baseball

Detroit and Baltimore

In August 1882, Robinson was playing minor league baseball in Natick, Massachusetts, when he was given a try-out with the Detroit Wolverines who were in the midst of a six-game losing streak against Providence and Boston.[2] Robinson made his major league debut on August 24, 1882, in the Wolverines' final game at Boston. He remained with the team for the remainder of the 1882 season, appearing in 10 games at shortstop, one as an outfielder and one as a pitcher.[1]

After his short stint with Detroit in 1882, Robinson spent the 1883 season in the minor leagues playing for the East Saginaw Grays in the Northwestern League.[1] He played shortstop and compiled a .215 batting average for East Saginaw.[2]

In 1884, Robinson returned to a major league with the Baltimore Monumentals of the Union Association. He played 71 games at third base for the Monumentals, but also demonstrated versatility by playing 14 games at shortstop, 11 games at catcher, and 11 games as a pitcher. He compiled a .267 batting average, led the league with 37 walks, and ranked fourth in the league with 101 runs scored. As a pitcher, he compiled a 3-3 record with a 3.48 earned run average (ERA), pitched three complete games, and led the Union Association with eight games finished as a relief pitcher.[1] The St. Louis Post-Dispatch called Robinson "the best all-around player in the Union Association."[3]

1885 season

In December 1884, after the Baltimore Monumentals disbanded, Robinson had offers from multiple teams but signed with the St. Louis Browns, the team that later became the St. Louis Cardinals, for $2,100.[4] The Browns had finished in fourth place in 1884, and Robinson was one of the final additions to a team that went on to win four consecutive American Association pennants under player-manager Charles Comiskey from 1885 to 1888.

During the 1885 season, Comiskey made use of Robinson's versatility, positioning him in the outfield for 52 games, second base for 19 games, catcher for five games, third base for two games, and even one game at first base. He also scored five runs in the 1885 World Series.[1]

1886 and 1887: peak seasons

In 1886, Robinson became the Browns' starting second baseman, a position he held for the next four years. Robinson had a good year at the plate in 1886, batting .274 with 71 RBIs. He ranked second in the league in times hit by pitch (15), fourth in stolen bases (51), fifth in bases on balls (64), seventh in times on base (211), eighth in on-base percentage (.377) and ninth in doubles (26). Applying the modern measure of Wins Above Replacement (WAR), Robinson had the best season of his career in 1886 with an Offensive WAR of 3.8, sixth best in the American Association.[1] Robinson also played a key role in helping the Browns win the 1886 World Series with a post-season batting average of .316, three RBIs and five runs.[1]

During the 1887 season, Robinson compiled career highs with 75 stolen bases, a .305 batting average, a .445 on-base percentage, 74 RBIs, 32 doubles and 17 times hit by pitch. His Offensive WAR rating of 3.7 is the sixth highest in the American Association for 1887. He also posted a .326 batting average in the 1887 World Series.[1]

1888 and 1889: master of the free pass

Prior to 1880, nine balls (pitches outside the strike zone) were required for a batsman to draw a walk,[5] and the major league record was 29 walks in a season.[6] The number of balls required to draw a walk was progressively reduced to eight balls in 1880, six in 1884, five in 1887, and, finally, four in 1889.[5]

Robinson was one of the first players to exploit fully the new rules governing bases on balls. In 1887, his 92 walks and 17 times hit by pitch elevated his on-base percentage to .445.[1] Then, in 1888 and 1889, Robinson became the master of the free pass. He set a new major league record in 1888 with 116 walks and broke his own record with 118 walks the following year.[6] Robinson actually tallied more walks (234) than hits (199) during the 1888 and 1889 seasons. His combined batting average in 1888 and 1889 was an anemic .219, but his 234 walks (and willingness to be hit by a pitch, a category in which he was a league leader five times) turned him into a potent offensive weapon with a .389 on-base percentage over the two seasons combined. His .400 on-base percentage in 1888 was the highest in the American Association.[1]

On strike in 1889

On May 2, 1889, Robinson began a strike that was the talk of baseball for a few days. Shortly before a game, team manager Charles Comiskey told Robinson to get a pair of padded playing trousers, as the trousers he was wearing were too small for him. Robinson sent a boy to retrieve the padded trousers from his room across the street from the ball park. Robinson gave the boy a note of explanation to show the gate keeper upon his return. When the boy returned, the gate keeper adamantly refused to admit the boy, saying he had strict instructions from the owner Chris von der Ahe not to admit anybody without a ticket. On learning what had happened, Robinson called the gate keeper and angrily berated him. The gate keeper was reduced to tears and complained to von der Ahe.[7]

The owner confronted Robinson and gave him a tongue-lashing in front of teammates and spectators seated in the grandstand. Robinson responded in kind, and von der Ahe imposed a $25 fine against Robinson. Robinson apologized for his angry outburst to the gate keeper, but asserted that the fine was unjust and refused to travel to Kansas City with the team unless the fine was removed. Initially, Robinson's teammates supported him and refused to board the train as well, but under threat of being fined themselves the other players took a later train. Robinson refused to return to the team until the fine was remitted, and von der Ahe announced that he would increase the fine by $25 for each day that Robinson failed to report.[7]

After a few games without Robinson, von der Ahe announced that a deal had been worked out between Comiskey and Robinson. Von der Ahe conceded that he "acted hastily" in berating Robinson on the bench. An adjustment was reached on the amount of the fine, and Robinson agreed to return to work.[8] However, ill feeling between Robinson and von der Ahe persisted and contributed to Robinson's decision to move to the Players' League in 1890.

Players' League

When Robinson jumped to the Players' League in 1890, playing for the Pittsburgh Burghers, the gap between Robinson's batting average and on-base percentage grew to a remarkable 205 points. During that season, Robinson had 70 hits for a .229 batting average, but his 101 bases on balls elevated his on-base percentage to .434, fourth highest in the Players' League.[1]

Over the four years from 1887 to 1890, Robinson drew 472 free passes (427 walks and 45 times hit by a pitch) and only 400 hits in 2,115 plate appearances, giving him a "free pass" percentage of .223 and an on-base percentage of .412.[1] Applying the modern measure of wins above replacement (WAR), Robinson's propensity to draw free passes made him one of the most valuable players in baseball during his peak years. His Offensive WAR ratings of 3.8, 3.7 and 3.6 ranked sixth in the American Association in 1886 and 1887 and eighth in 1888.[1]

Cincinnati and Washington

In April 1891, Robinson signed to play second base for the Cincinnati Kelly's Killers. By that time, Robinson had developed a reputation as a drinker, and the Sporting Life reported on the signing as follows: "Robby is a brilliant player, and if he will refrain from his bibulous habits he will be a great help to the club."[9] Robinson compiled a .178 batting average in 97 games for Cincinnati, but his talent for drawing walks, totaling 68 in 1891, gave him a respectable .328 on-base percentage.[1] The Kelly's Killers disbanded in August 1891, and Robinson returned to the Browns for a single game late in the season.[1][10]

Robinson concluded his major league playing career with Washington Senators in 1892. He appeared in 58 games at third base for Washington and compiled a .179 batting average.[1] According to one source, Robinson's "skills and health had slipped badly" by the 1892 season.[2] Robinson appeared in his last major league game on August 10, 1892.[1]

Defensive woes

While Robinson played at every position other than center field, and even pitched a few games, he spent most of his career as an infielder, playing 698 games as a second baseman, 143 as a third baseman, and 66 as a shortstop.[1] For an infielder who posted batting averages as low as .177 in 1891, .179 in both 1882 and 1892, and .208 in 1889, the historical expectation would be the classic "good field, no hit" infielder.[11]

At least two modern accounts support the notion that Robinson was a good fielder. In his 1999 book on the early St. Louis Browns, J. Thomas Hetrick stated:

Performing gloveless at second base, Robinson was known for his range, accurate throwing arm, and double-play acrobatics. Ambidextrous, Robinson sometimes startled the opposition with lefthanded throws across his chest to nail base runners heading to third.[12]

Similarly, baseball historian Robert L. Tiemann acknowledged that Robinson's refusal to wear a glove rendered him "less than outstanding on ground balls", but praised him for his "good range" and "accurate throws" and concluded that, overall, Robinson "excelled at second base because of his agility and quickness."[2]

While Robinson did rank second among the American Association's second basemen with 66 double plays turned in 1886, the historical record does not support the claim that he was an excellent, or even average, fielder. To the contrary, he never ranked higher than fifth in range factor, assists or putouts among the second basemen in the eight-team American Association. Moreover, he compiled a career fielding percentage of .897 and consistently ranked at or near the bottom of the American Association's second basemen in fielding percentage. He committed 103 errors in 1886, including a league-leading 95 errors at second base, and ranked among the league leaders in errors by a second baseman every year from 1886 to 1891. Perhaps most tellingly, and even though he played only nine major league seasons at second base, his 471 career errors at the position continue to rank 11th all time in major league history.[1]

Although every player has an off day, Robinson reached an all-time low in fielding on May 26, 1891, when, while playing for the Cincinnati Kelly's Killers, he had seven fielding chances and committed seven errors.[13]

Death

In April 1893, less than eight months after Robinson played in his last major league game, the Sporting Life newspaper reported that a private telegram said that Robinson was dying of consumption (pulmonary tuberculosis) and had been "reduced to a mere skeleton, weighing in the neighborhood of ninety pounds." He had reportedly signed a contract to play for Louisville in 1893, but traveled instead to Hot Springs, Arkansas, to receive treatment for his illness.[14]

Two weeks later, Sporting Life published a retraction of its account and noted: "The story that second baseman Yank Robinson is dying with consumption is untrue. Yank is at Hot Springs and is in good health. The tale was probably designed as a big free advertisement for Yank, and in that particular was successful. It probably however lost him a chance of an engagement by Louisville."[15]

The following year, in August 1894, Robinson died from tuberculosis at the St. Louis home of friend Patsy Tebeau. He was 34 years old and left $770 to be divided between Tebeau and a brother in Cleveland.[16] He was buried at the Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis.[17]

References

- "Yank Robinson". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- Robert L. Tiemann (August 2012). Nineteenth Century Stars: 2012 Edition. SABR. pp. 226–227. ISBN 9781933599298.

- Jon David Cash (2002). Before They Were Cardinals: Major League Baseball in Nineteenth-Century. University of Missouri Press. p. 97.

- Cash, Before They Were Cardinals, p. 98.

- 2001 Official Major League Baseball Fact Book. St. Louis, Missouri: The Sporting News. 2001. pp. 276–280. 0-89204-646-5.

- "Progressive Leaders & Records for Bases on Balls". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Revolt in the St. Louis Team: A Fine Resented – Details of the Row – General Sporting Intelligence" (PDF). Sporting Life. May 8, 1889. p. 1.

- "St. Louis Siftings" (PDF). Sporting Life. May 15, 1889. p. 6.

- "Cincinnati Affairs" (PDF). Sporting Life. April 11, 1891. p. 6.

- "Presto, Change! Unexpected and Important Move by the Association: Cincinnati Evacuated and Milwaukee Admitted" (PDF). Sporting Life. August 22, 1891. p. 2.

- The notion of the Mendoza Line was not developed until the 1970s, but Robinson dropped below a .200 batting average three times and came close in 1889.

- J. Thomas Hetrick (1999). Chris Von Der Ahe and the St. Louis Browns. Scarecrow Press. p. 38. ISBN 0810834731.

- "On This Date: May 26". Cincinnati Sports Journal.

- "Alas, Poor Robinson! The Once Famous Ball Player Dying of Consumption" (PDF). Sporting Life. April 1, 1893. p. 1.

- "Situation At Large" (PDF). Sporting Life. April 15, 1893.

- Daniel Merle Pearson (1993). Baseball in 1889: Players Vs. Owners. Popular Press. p. 204. ISBN 0879726199.

- Retrosheet