Yazid II

Yazid ibn Abd al-Malik (Arabic: يزيد بن عبد الملك, romanized: Yazīd ibn ʿAbd al-Malik; c. 690/91 — 26 January 724), also referred to as Yazid II, was the ninth Umayyad caliph, ruling from 9 February 720 until his death in 724. Although he lacked administrative or military experience, he derived prestige from his lineage, being a descendant of both ruling branches of the Umayyad dynasty, the Sufyanids who founded the Umayyad Caliphate in 661 and the Marwanids who succeeded them in 684. He was designated by his half-brother, Caliph Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik (r. 715–717), as second-in-line to the succession after their cousin Umar II (r. 717–720), as a compromise with the sons of Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705).

| Yazid II يزيد بن عبد الملك | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khalīfah Amir al-Mu'minin | |||||

Gold dinar of Yazid II | |||||

| 9th Caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate | |||||

| Reign | 9 February 720 – 26 January 724 | ||||

| Predecessor | Umar II | ||||

| Successor | Hisham | ||||

| Born | c. 690/91 Damascus, Umayyad Caliphate | ||||

| Died | 26 January 724 (aged c. 33–34) (24 Sha'ban 105 AH) Irbid, Umayyad Caliphate | ||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Umayyad | ||||

| Father | ʿAbd al-Malik | ||||

| Mother | ʿĀtika bint Yazīd | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

He reversed the reformist policies of Umar II, mainly by reimposing the jizya (poll tax) on the mawali (non-Arab Muslim converts) and resuming the war efforts on the frontiers of the Caliphate, especially against the Khazars in the Caucasus and the Byzantines in Anatolia. Yazid's moves were in line with the desires of the Arab militarist camp and the Umayyad dynasty but did not solve the fiscal crisis of the Caliphate as war booty had become insufficient and the reimposition of the jizya met strong resistance from the converted populations in the large provinces of Khurasan and Ifriqiya. He issued an iconoclastic edict whereby Christian icons were destroyed in churches across the caliphate, influencing the Byzantine emperor Leo III (r. 717–741) to institute a similar edict in his domains.

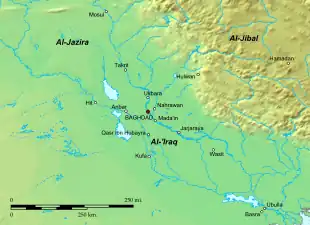

Yazid reintroduced Syrian troops to enforce Umayyad rule in Iraq, where their domination was long resented. One of the first events of his reign was the wide-scale rebellion of the Iraqis under Yazid ibn al-Muhallab, whose suppression marked the end to the serious anti-Umayyad revolts in the restive province. Ibn al-Muhallab was a champion of the Yamanis and Yazid's appointment of Qaysi partisans to rule Iraq escalated the factional tensions there, though elsewhere Yazid balanced the interests of the two rival factions. The deadly suppression of the Muhallabids became a rallying cry for revenge during the Abbasid Revolution, which toppled the Umayyads in 750.

Early life

Yazid was born in Damascus, the capital of the Umayyad Caliphate, c. 690/91.[1] He was the son of Caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705) and his influential wife Atika, the daughter of Yazid II's namesake, Caliph Yazid I (r. 680–683).[1] Sources occasionally refer to him as 'Ibn Atika'.[2] His kunya (patronymic) was Abu Khalid and he was nicknamed al-Fata (lit. 'the Youth').[3] Yazid II's pedigree united his father's Marwanid branch of the Umayyad dynasty, in power since 684, and the Sufyanid branch of Yazid I and the latter's father Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680), founder of the Umayyad Caliphate.[1]

Yazid did not possess military or administrative experience before his reign.[1] He rarely left Syria except for a number of visits to the Hejaz (western Arabia, home of the Islamic holy cities Mecca and Medina),[1] including once for the annual Hajj pilgrimage sometime between 715 and 717.[4]

He was possibly granted control of the region around Amman by Abd al-Malik.[5] He built the desert palaces of al-Qastal and al-Muwaqqar, both in the general vicinity of Amman. The palaces are conventionally dated to his caliphate, though a number of archaeologists suggest Yazid began their construction before 720.[6]

Family

Yazid established marital ties to the family of al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf (d. 714), the powerful viceroy of Iraq for his father, Caliph Abd al-Malik, and brother, al-Walid I (r. 705–715). He married al-Hajjaj's niece, Umm al-Hajjaj, the daughter of Muhammad ibn Yusuf al-Thaqafi.[7][8] During her uncle's lifetime, she gave birth to Yazid's sons: al-Hajjaj, who died young, and al-Walid II, who became caliph in 743.[7] Yazid was also married to Su'da bint Abd Allah ibn Amr, a great-granddaughter of Caliph Uthman (r. 644–656), who mothered Yazid's son and daughter Abd Allah and A'isha.[9] Su'da's cousin, Sa'id ibn Khalid ibn Amr ibn Uthman, is held by the 9th-century historian al-Ya'qubi to have "exercised the most influence upon Yazīd".[10][lower-alpha 1] Overall, Yazid had six children from his two wives and eight by slave concubines.[12] His other sons were al-Nu'man,[13] Yahya, Muhammad, al-Ghamr, Sulayman, Abd al-Jabbar, Dawud, Abu Sulayman, al-Awwam and Hashim.[10]

Reign

Accession

By dint of his descent, Yazid was a natural candidate for the succession to the caliphate.[1] A noble Arab maternal lineage held political weight during this period in the Caliphate's history,[14] and Yazid took pride in his maternal Sufyanid descent, viewing himself superior to his paternal half-brothers.[7] He was chosen by his half-brother Caliph Sulayman (r. 715–717) as the second-in-line in the caliphal succession after their first cousin, Umar II, who ruled from 717 to 720.[1] Yazid acceded at the age of 29 after the death of Umar II on 9 February 720.[1][15] For most of his reign, he resided in Damascus or his estates in Jund al-Urdunn (the military district of Jordan),[1] which was centered in Tiberias and roughly corresponded with the Byzantine province of Palaestina Secunda.[16]

Suppression of the Muhallabids

Shortly before or immediately after Yazid's accession, the veteran commander and disgraced governor of Iraq and the vast eastern province of Khurasan, Yazid ibn al-Muhallab, escaped from the fortress of Aleppo where Umar II had him imprisoned.[17][18] During Sulayman's reign, Ibn al-Muhallab, an enemy of al-Hajjaj, had been responsible for the torture and deaths of members of al-Hajjaj's family, Yazid's in-laws, and feared retaliatory maltreatment when Yazid's accession became apparent.[17] Yazid had long held suspicions, nurtured by al-Hajjaj, of Ibn al-Muhallab's and the Muhallabid family's influence and ambitions in Iraq and the eastern Caliphate.[19]

Evading the pursuit of Umar's or Yazid's commanders, Ibn al-Muhallab made his way to Basra, one of the main garrison towns of Iraq and the center of his family and Azd Uman tribe.[17] On Yazid's orders, Basra's governor Adi ibn Artat al-Fazari arrested many of Ibn al-Muhallab's brothers and cousins before his arrival to the city.[17][20] Ibn Artat was unable to stop Ibn al-Muhallab's entry and the latter, with support from his Yamani tribal allies in the Basra garrison, besieged Ibn Artat in the city's citadel.[17] The Qays–Mudar factions of the garrison, though traditional rivals of the Yaman and unsympathetic to Ibn al-Muhallab, did not actively or effectively oppose him.[21] Ibn al-Muhallab seized the citadel, captured the governor and established control over Basra.[21] Yazid pardoned him, but Ibn al-Muhallab continued his opposition, declaring jihad (holy war) against the caliph and the Syrian troops who enforced Umayyad authority in Iraq.[21] Umar II had likely withdrawn most of the Syrians from Wasit, their main garrison in Iraq, and Ibn al-Muhallab captured the city with ease.[22] Most of the qurra (pious Qur'an readers) and the mawali (non-Arab Muslim converts) of Basra supported Ibn al-Muhallab's cause, with the exception of the prominent theologian al-Hasan al-Basri.[23] The Iranian dependencies of Basra, namely Ahwaz, Fars and Kerman, joined the revolt, though not Khurasan, where Qays–Mudar troops counterbalanced the pro-Muhallabid Yamani faction in the province's garrisons.[24]

Ibn al-Muhallab advanced toward Kufa, the other main garrison center of Iraq, where he attracted support across the tribal spectrum and among many of its noble Arab households.[25] In the meantime, Yazid dispatched his kinsmen, the veteran commanders Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik and al-Abbas ibn al-Walid, to suppress the revolt.[26] They killed Ibn al-Muhallab and routed his army near Kufa on 24 August 720.[27] Yazid ordered the executions of the roughly two hundred prisoners-of-war captured from Ibn al-Muhallab's camp, while Ibn al-Muhallab's son Mu'awiya ordered the execution of Ibn Artat and his thirty supporters incarcerated in Wasit.[28] Afterward, the Umayyad authorities pursued and killed many of the Muhallabids, including nine to fourteen boys who were sent to Yazid and executed by his order.[29][30] The Muhallabid revolt's suppression marked the last of the great anti-Umayyad uprisings in Iraq.[31]

Escalation of Qays–Yaman factionalism

The defeat of the Yamani Muhallabids and Yazid's successive appointments to Iraq of the pro-Qaysi Maslama—who was shortly dismissed for not forwarding the provincial tax surplus to the caliph's treasury—and Maslama's Qaysi lieutenant, Umar ibn Hubayra al-Fazari, signaled a triumph for the Qays–Mudar faction in the province and its eastern dependencies.[32] According to the historian Julius Wellhausen, "the proscription of the whole of the prominent and powerful [Muhallabid] family, a measure hitherto unheard of in the history of the Umaiyids [sic], came like a declaration of war against the Yemen [faction] in general, and the corollary was that the government was degenerating into a Qaisite party-rule".[19] Wellhausen blames the caliph for the escalation of factionalism and attributed the appointment of Ibn Hubayra to his own desire for revenge against the Muhallabids' Yamani backers.[19] The Yamani-affiliated tribes of Khurasan viewed the events as a humiliation and during the Abbasid Revolution which toppled the Umayyads in 750 they adopted as one of their slogans "revenge for the Banu Muhallab [Muhallabids]".[33]

Orientalist Henri Lammens considers Yazid's portrayal as "a pro-Mudar and anti-Yaman extremist" as "unfair, as he actually tried to balance the conflicting groups, just as other Umayyad rulers did".[1] Yazid did not champion the Qays over the Quda'a, the major component of the Yaman in Syria.[19] Indeed, members of the Quda'a's principal tribe, the Banu Kalb, had formed the core of the caliph's army during the suppression, pursuit and elimination of the Muhallabids.[19] He appointed Yamani governors to the large provinces of Ifriqiya (central North Africa) and the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia) and its dependent districts of Adharbayjan and Armenia.[1]

Fiscal and military policies

The expenses of enforcing Umayyad rule in Iraq and the expansionist war efforts along multiple fronts, including the enormous cost of the failed sieges of Constantinople in 717–718, had erased much of the monetary gains from the conquests of Transoxiana, Sind and the Iberian Peninsula under al-Walid I, causing a financial crisis in the Caliphate.[34] Among the solutions of Yazid's predecessor to the fiscal burden were the withdrawal of the Syrians from Iraq, a halt on conquests and near elimination of grants to Umayyad princes, as well as an unrealized goal to withdraw Arab troops altogether from Transoxiana, the Iberian Peninsula and Cilicia.[34] The most significant reforms of Umar II granted equality to the mawali in Khurasan, Sind, Ifriqiya and the Iberian Peninsula by abolishing the jizya, the poll tax traditionally exacted on non-Muslim subjects but in practice extended to non-Arab Muslim converts, and instituting equal pay for mawali in the ranks of the Caliphate's Arab-dominated armies.[1][35] According to Blankinship, the reforms favoring the mawali may have been guided by Umar II's piety but also a fiscal consideration: if equal treatment with the Arabs made the government popular with the mawali it could translate into delegating an increased security role for the mawali in their native provinces and their enthusiastic defense of the Caliphate's frontiers, thereby reducing the expense of deploying and garrisoning Arab troops.[34]

Yazid attempted to reverse, with limited success, the reforms of Umar II, which were opposed by the Arab militarist camp in the Caliphate and the Umayyad ruling family.[1] During Umar II's rule the militarist camp led by Maslama may have accepted a temporary pause in activity to recover from the Constantinople debacle.[36] Under Yazid, Maslama and his proteges, including Ibn Hubayra, were restored or appointed to senior commands, Syrian garrisons were reintroduced to Iraq, the traditional annual raids against the Byzantines and the war with the Khazars were restarted, and the grants of estates or generous sums to Umayyad princes resumed.[37] Although Yazid's policies were presumably meant to gain the backing of the ruling elite and restore the flow of war spoils, they proved insufficient to finance the Caliphate's troops, particularly as booty had become increasingly difficult to obtain by the Arab expeditionary forces.[37]

To fill the depleted coffers of the caliphal treasury Yazid turned to the fifth of provincial tax revenues officially owed to the caliph. Historically, the provinces neglected to forward the revenues if political conditions allowed, and governors often pilfered such funds. To ensure the flow of revenues to the treasury, Yazid appointed governors based on the example set by al-Hajjaj, i.e. upright, meticulously loyal, and ruthless in the collection of taxes.[37] Unlike the era of al-Hajjaj, however, Yazid applied this principle for the first time to Ifriqiya, Khurasan, Sind and the Iberian Peninsula.[37] A major aspect of his policy was the reinstatement of the jizya on the mawali,[37] which alienated the mawali in the aforementioned provinces.[1]

In Ifriqiya, the caliph's governor Yazid ibn Abi Muslim, himself a mawla from Iraq and a protégé of al-Hajjaj, was assassinated by his Berber guard in 720, shortly after his appointment, for attempting to reinstate the jizya.[1] Many, if not most, Berbers had embraced Islam and commanded a strong position in the army, unlike mawali in other parts of the Caliphate.[38] The Berbers reinstalled Ibn Abi Muslim's predecessor Ismail ibn Abd Allah ibn Abi al-Muhajir and notified Yazid, who approved the change.[39] The incident in Ifriqiya was a blow to the Caliphate's prestige in North Africa and served as a harbinger for the Berber Revolt in 740–743.[1] The reinstatement of the jizya in Khurasan in 721/22 by Ibn Hubayra's deputy Sa'id ibn Amr al-Harashi led to revolts and wars in the province that continued for twenty years and partly contributed to the Abbasid Revolution.[1] In Egypt pay increases to the indigenous mawali sailors of the Muslim fleet were reversed.[37]

War against the Khazars

In March 722 the Syrian army of Yazid's governor in Armenia and Adharbayjan, Mi'laq ibn Saffar al-Bahrani, was routed by the Khazars in Armenia, south of the Caucasus. The defeat marked the culmination of the Caliphate's winter campaign against the Khazars and resulted in considerable Syrian losses.[40] To avenge this defeat, Yazid II sent al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah at the head of a 25,000-strong army of Syrians, who pushed into the Caucasus homeland of the Khazars and took their capital of Balanjar on 22 August.[41] The main body of the highly mobile Khazars avoided the Muslims' pursuit and their presence compelled al-Jarrah to withdraw to Warthan south of the Caucasus and request reinforcements from Yazid.[41] In 723 he led another raid north of Balanjar but made no substantive gains.[41]

Iconoclastic edict

According to Greek sources, including Patriarch John V of Jerusalem (d. 735), Theophanes the Confessor (d. 818) and Patriarch Nikephoros I of Constantinople (d. 828), Yazid issued an edict ordering the destruction of all icons in Christian churches across the Caliphate under the influence of a Jewish magician from Tiberias, called Beser or Tessarakontapechys, who promised Yazid a long life of fortune in return.[42] Syriac sources further note that Yazid entrusted Maslama to execute the order and that the edict influenced the Byzantine emperor Leo III (r. 717–741) to enact his own iconoclastic policy in the Byzantine Empire.[43] The Egypt-based Arabic historians al-Kindi (d. 961), Bishop Severus ibn al-Muqaffa (d. 987) and al-Maqrizi (d. 1442) also make note of the edict and describe its execution in Egypt.[44] Medieval historians cite different years for Yazid's edict, but modern historian Alexander Vasiliev holds that July 721, the date cited by Patriarch John V, is the most reliable.[45] The order was reversed by Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik (r. 724–743).[44]

Death

Yazid died of consumption[46] in Irbid, a town in the Balqa subdistrict of Jund Dimashq (the military division of Damascus corresponding to Transjordan) on 24 Sha'ban 105 AH (26 January 724).[1][lower-alpha 2] His son al-Walid or half-brother Hisham led his funeral prayers.[47] Yazid had intended to appoint al-Walid as his immediate successor but was persuaded by Maslama to appoint Hisham instead, followed by al-Walid.[48]

Portrayal in sources

In traditional Islamic sources, Yazid and his son al-Walid have "a reputation for unabashed extravagance and hedonism", contrasting with Umar II's piety and Hisham's austerity.[49] According to historian Khalid Yahya Blankinship, despite the "momentous events of his reign", both the traditional and modern sources frequently depict Yazid as "a frivolous slave to passion", especially to his singing slave girls Hababa and Sallama,[1] whom he acquired after his accession.[46] Hababa's talents, beauty and charm supposedly captivated the caliph, causing him to neglect his duties, to the chagrin of his inner circle, especially Maslama.[46] According to this narrative, Yazid had secluded himself with Hababa at his estate in the wine country of Beit Ras (Capitolias), near Irbid. There, Hababa died when she choked on a grape or pomegranate seed Yazid had playfully tossed into her mouth. Grief-stricken, he died a few days later.[50] Blankinship considers the portrayal of Yazid as being heavily influenced by Hababa to be "much exaggerated", though he likely patronized poets and had a "refined artistic taste".[1]

See also

- Khalid ibn Yazid, maternal uncle of Yazid II.

- Marwan al-Akbar, brother of Yazid II.

- Abd al-Aziz, nephew of Yazid II.

Notes

- Sa'id ibn Khalid ibn Amr ibn Uthman was "among the wealthiest people of his time", according to the historian Asad Ahmed, who had forged strong links with his Umayyad kinsmen from the ruling Marwanid branch of the family. He was married to Yazid II's paternal aunt, Umm Amr bint Marwan, and wed two of his daughters to Yazid's half-brother, Caliph Hisham, and son, Caliph al-Walid II, respectively.[11]

- The 9th-century historians al-Tabari and al-Ya'qubi place Yazid's death on 28 January and 29 January, respectively.[47][10]

References

- Lammens & Blankinship 2002, p. 311.

- Marsham 2022, p. 35.

- Powers 1989, pp. 193–194.

- Powers 1989, p. 195.

- Bacharach 1996, pp. 30, 32, 33.

- Bacharach 1996, p. 36.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 312.

- Powers 1989, pp. 89–90.

- Ahmed 2011, p. 123.

- Gordon et al. 2018, p. 1031.

- Ahmed 2011, pp. 119–120.

- Marsham 2022, p. 40.

- Hillenbrand 1989, p. 70.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 312, note 1.

- Powers 1989, p. 105.

- Cobb 2000, p. 882.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 313.

- Powers 1989, p. 80, note 287.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 322.

- Powers 1989, p. 112.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 314.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 313, 316.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 314–315.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 315–316.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 316–317.

- Powers 1989, p. 127.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 318.

- Powers 1989, pp. 140–141.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 318–319.

- Powers 1989, pp. 144–146.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 108.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 319–320.

- Hawting 2000, p. 76.

- Blankinship 1994, pp. 84–85.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 86.

- Blankinship 1994, pp. 86–87.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 87.

- Blankinship 1994, pp. 87–88.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 323.

- Blankinship 1994, pp. 121–122.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 122.

- Vasiliev 1956, pp. 27–33.

- Vasiliev 1956, p. 37.

- Vasiliev 1956, pp. 39–40.

- Vasiliev 1956, p. 47.

- Pellat 1971, p. 2.

- Powers 1989, p. 194.

- Blankinship 1989, p. 87, note 439.

- Fowden 2004, p. 147.

- Fowden 2004, pp. 147–148.

Bibliography

- Ahmed, Asad Q. (2011). The Religious Elite of the Early Islamic Ḥijāz: Five Prosopographical Case Studies. Oxford: University of Oxford Linacre College Unit for Prosopographical Research. ISBN 978-1-900934-13-8.

- Bacharach, Jere L. (1996). "Marwanid Umayyad Building Activities: Speculations on Patronage". Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Cultures of the Islamic World. Brill. 13: 27–44. doi:10.1163/22118993-90000355. ISSN 2211-8993. JSTOR 1523250.

- Gordon, Matthew S.; Robinson, Chase F.; Rowson, Everett K.; Fishbein, Michael (2018). The Works of Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-Yaʿqūbī (Volume 3): An English Translation. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-35621-4.

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya, ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXV: The End of Expansion: The Caliphate of Hishām, A.D. 724–738/A.H. 105–120. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-569-9.

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7.

- Cobb, P. M. (2000). "Al-Urdunn: 2. History, (a) Up to 1250". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume X: T–U (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 882–884. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Hawting, Gerald R. (2000). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661–750 (Second ed.). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24072-7.

- Hillenbrand, Carole, ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXVI: The Waning of the Umayyad Caliphate: Prelude to Revolution, A.D. 738–744/A.H. 121–126. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-810-2.

- Fowden, Garth (2004). Qusayr 'Amra: Art and the Umayyad Elite in Late Antique Syria. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23665-3.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Lammens, H. & Blankinship, Kh. Y. (2002). "Yazīd (II) b. ʿAbd al-Malik". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume XI: W–Z (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 311. ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- Marsham, Andrew (2022). "Kinship, Dynasty, and the Umayyads". The Historian of Islam at Work: Essays in Honor of Hugh N. Kennedy. Leiden: Brill. pp. 12–45. ISBN 978-90-04-52523-8.

- Pellat, Ch. (1971). "Ḥabãba". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume III: H–Iram (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 2. OCLC 495469525.

- Powers, David S., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXIV: The Empire in Transition: The Caliphates of Sulaymān, ʿUmar, and Yazīd, A.D. 715–724/A.H. 96–105. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0072-2.

- Vasiliev, A. A. (1956). "The Iconoclastic Edict of the Caliph Yazid II, A. D. 721". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 9: 23–47. doi:10.2307/1291091. JSTOR 1291091.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1927). The Arab Kingdom and Its Fall. Translated by Margaret Graham Weir. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. OCLC 752790641.