Yan Xishan

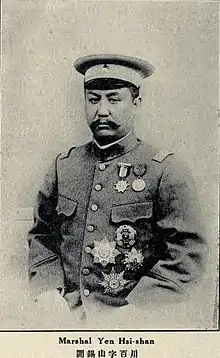

Yan Xishan or Yen Hsi-shan (IPA: [jɛ̌n ɕíʂán]; 8 October 1883 – 22 July 1960) was a Chinese warlord who served in the government of the Republic of China. He effectively controlled the province of Shanxi from the 1911 Xinhai Revolution to the 1949 Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War. As the leader of a relatively small, poor, remote province, he survived Yuan Shikai, the Warlord Era, the Nationalist Era, the Japanese invasion of China and the subsequent civil war, being forced from office only when the Nationalist armies with which he was aligned had completely lost control of the Chinese mainland, isolating Shanxi from any source of economic or military supply. He has been viewed by Western biographers as a transitional figure who advocated using Western technology to protect Chinese traditions, while at the same time reforming older political, social and economic conditions in a way that paved the way for the radical changes that would occur after his rule.[1]

Yan Xishan | |

|---|---|

閻錫山 Yen Hsi-shan | |

Gen. Yan Xishan | |

| President of the Republic of China | |

| Acting 20 November 1949 – 28 February 1950 | |

| Premier | Yan Hsi-shan |

| Preceded by | Li Zongren |

| Succeeded by | Chiang Kai-shek |

| Premier of the Republic of China | |

| In office 3 June 1949 – 7 March 1950 | |

| President | Li Zongren (acting) Yan Hsi-shan (acting) Chiang Kai-shek |

| Vice Premier | Chia Ching-teh Chu Chia-hua |

| Preceded by | He Yingqin |

| Succeeded by | Zhou Enlai (as Premier of the People's Republic of China) Chen Cheng |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 8 October 1883 Wutai County, Xinzhou, Shanxi, Qing Empire |

| Died | 22 July 1960 (aged 76) Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China |

| Political party | Kuomintang Progressive Party |

| Awards | Order of Blue Sky and White Sun Order of the Sacred Tripod Order of the Cloud and Banner Order of Rank and Merit Order of the Precious Brilliant Golden Grain Order of Wen-Hu |

| Nickname | "Model Governor" |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1911–1949 |

| Rank | |

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | |

| Yan Xishan | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 閻錫山 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 阎锡山 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Early life

Childhood

Yan Xishan was born during the late Qing dynasty in Wutai County, Xinzhou, Shanxi, to a family who had been bankers and merchants for generations (Shanxi was known for its many successful banks until the late 19th century). As a young man he worked for several years at his father's bank while he pursued a traditional Confucian education at a local village school. After his father was ruined by a late 19th-century depression, which ravaged the Chinese economy, Yan enrolled in a free military school that was run and financed by the Manchu government in Taiyuan. While studying at the school, he was first introduced to mathematics, physics, and various other subjects imported directly from the West. In 1904, he was sent to Japan to study at the Tokyo Shimbu Gakko, a military preparatory academy, and he later entered the Imperial Japanese Army Academy from which he graduated in 1909.[2]

Experience in Japan

Over the five years that Yan studied in Japan, he became impressed by the country's successful efforts at modernization. He observed the progress made by the Japanese, whom the Chinese had previously considered unsophisticated and backward, and began to worry about the consequences if China were to fall behind the rest of the world. That formative experience was later cited as a period of great inspiration for his later efforts to modernize Shanxi.[2]

Yan eventually concluded that the Japanese had successfully modernized largely because of the government's abilities to mobilize its populace in support of its policies and to the close respectful relationship that existed between the military and civilian populations. He attributed the surprising Japanese victory in the 1905 Russo-Japanese War to the enthusiastic mobilization of the Japanese public in supporting the military. After returning to China in 1910, he wrote a pamphlet warning China that it was in danger of being overtaken by Japan unless it developed a local form of bushido.[3]

Even before studying in Japan, Yan had become disgusted with the open and widespread corruption of officials in Shanxi and had become convinced that China's relative helplessness in the 19th century was the result of the Qing dynasty's generally hostile attitude towards modernization and industrial development and its grossly inept foreign policy. While he was in Japan, he met Sun Yat-sen and joined his Tongmenghui (Revolutionary Alliance), a semi-secret society dedicated to overthrowing the Qing dynasty. He also attempted to popularize Sun's ideology by organizing an affiliated "Blood and Iron Society" within the ranks of Chinese students at the Imperial Japanese Army Academy. The goal of the student group was to organize a revolution that would lead to the creation of a strong and united China, similar to how Otto von Bismarck had created a strong and united Germany.[3] Yan also joined an even more militant organization of Chinese revolutionaries, the "Dare-to-Die Corps."[4]

Return to China

When Yan returned to China in 1909, he was assigned as a division commander of the New Army in Shanxi[5] but secretly worked to overthrow the Qing.[4] During the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, Yan led local revolutionary forces in driving Manchu troops from the province and proclaimed it independent of the Qing government. He justified his actions by attacking the Qing's failure to repel foreign aggression, and he promised a wide range of social and political reforms.[5]

Career in early republic

Conflict with Yuan Shikai

In 1911 Yan hoped to join forces with another prominent Shanxi revolutionary, Wu Luzhen, to undermine Yuan Shikai's control of north China, but the plans were aborted after Wu was assassinated.[4] Yan was elected military governor by his comrades but was unable to prevent a subsequent invasion by the troops of Yuan Shikai, who occupied most parts of Shanxi in 1913. During Yuan's invasion, Yan survived only by withdrawing northward and aligning himself with a friendly insurgent group in neighboring Shaanxi province. By avoiding a decisive military confrontation with Yuan, Yan preserved his own base of power. Though he was friends with Sun Yat-sen, Yan withheld support for him in the 1913 "Second Revolution" and instead ingratiated himself with Yuan, who allowed him to return as military governor of Shanxi, commanding a military that was then staffed by Yuan's own henchmen.[5] In 1917, shortly after Yuan Shikai's death, Yan solidified his control over Shanxi, ruling there uncontested.[6] After Yuan's death in 1916, China descended into a period of warlordism.

The determination of Shanxi to resist Manchu rule was a factor leading Yuan to believe that only the abolition of the Qing dynasty could bring peace to China and end the civil war. Yan's inability to resist Yuan's military domination of northern China was a factor contributing to Sun Yat-sen's decision not to personally pursue the presidency of the Republic of China, which was established after the end of the Qing dynasty. The demonstrated futility of opposing Yuan's military domination must have made it seem more important to Sun to bring Yuan into the process of ruling the republic and to come to terms with his (potential) enemy.[7]

Efforts to modernize Shanxi

By 1911, Shanxi was one of the poorest provinces in China. Yan believed that unless he modernized and revived Shanxi's economy and infrastructure, he would be unable to prevent Shanxi from being overrun by rival warlords.[8] A military defeat in 1919 inflicted by a rival warlord convinced Yan that Shanxi was not sufficiently developed to compete for hegemony with other warlords, and he avoided the violent national politics of the time by enforcing a neutrality policy on Shanxi to free his province from the civil wars. Instead of participating in the ongoing civil wars, Yan devoted himself almost exclusively to modernizing Shanxi and developing its resources. The success of his reforms were sufficient for him to be dubbed by outsiders as the "Model Governor," with Shanxi the "Model Province."[5]

In 1918, there was an outbreak of bubonic plague in northern Shanxi that lasted for two months and killed 2,664 people. Yan dealt with the epidemic by issuing instructions on modern germ theory and plague management to his officials. Yan instructed people that the plague was caused by tiny germs that were breathed into the lungs, the disease was incurable, and the only way to keep the disease from spreading was physical isolation of the infected. He ordered his officials to keep infected family members, neighbors, or even entire infected communities from each other by threat of police force if necessary. Yan's promotion of germ theory and his enforcement of physical isolation to reduce the effect of epidemics were not completely accepted by the local population, and in some areas, the local people resisted the measures.[9]

Yan's determination to modernize Shanxi was partly inspired by his interactions with the foreign doctors and personnel who arrived in Shanxi in 1918 to help him suppress the epidemic. He was impressed with the zeal, talents, and modern outlook of the personnel and subsequently compared foreigners favorably to his own conservative and generally apathetic officials. Conversations with other famous reformers, including John Dewey, Hu Shih, and Yan's close friend H.H. Kung, reinforced his determination to westernize Shanxi.[10]

Yan attempted to modernize the state of medicine in China by funding the Research Society for the Advancement of Chinese Medicine, based in Taiyuan, in 1921. Highly unusual in China at the time, the school had a four-year curriculum and included courses in both Chinese and western medicine. Its courses were taught in English, German, and Japanese. The main skills that Yan hoped physicians trained at the school would learn were a standardized system of diagnosis; sanitary science, including bacteriology; surgical skills, including obstetrics; and the use of diagnostic instruments. Yan hoped that his support of the school would eventually lead to increased revenues in the domestic and international trade of Chinese drugs, improved public health, and improved public education. Yan's interest in having such a school active in Shanxi was sparked after staying in a western hospital in Japan for three months in which he was impressed by seeing modern medical equipment, including X-rays and microscopes, for the first time.[11][12]

Yan continued to promote a tradition of Chinese medicine that was informed by Western medical science throughout his period of governance, but much of the teaching and publication that the school of medicine produced was limited to the area around Taiyuan. By 1949, three of the seven government-run hospitals were in the city. In 1934, the province produced a ten-year-plan that envisaged employing a hygiene worker in every village, but the advent of World War II and the subsequent civil war made it impossible to carry those plans out.[13]

Involvement in Northern Expedition

_IE_Oberholtzer_(probable)_(RESTORED)_(4072600660).jpg.webp)

To maintain Shanxi's neutrality and to free it from serious military confrontations with rival warlords, Yan developed a strategy of shifting alliances between various warring cliques and inevitably joining only winning sides. Although he was weaker than many of the warlords who surrounded him, he often held the balance of power between neighboring rivals, and even those whom he betrayed hesitated to retaliate against him in case they needed his support in the future. To resist the domination of the Manchurian warlord Zhang Zuolin, Yan allied himself with the forces of Chiang Kai-shek in 1927, during the Nationalists' Northern Expedition. While aiding Chiang, Yan's occupation of Beijing in June 1928 brought the Northern Expedition to a successful conclusion.[14] Yan's assistance to Chiang was rewarded shortly afterwards by his being named minister of the interior[15] and deputy commander-in-chief of all Kuomintang armies[16] Yan's support for Chiang's military campaigns and his suppression of Communists influenced Chiang to recognize Yan as the governor of Shanxi and to allow him to expand his influence into Hebei.[4]

Involvement in Central Plains War

Yan's alliance with Chiang was interrupted in 1929 when Yan joined Chiang's enemies to establish an alternative national government in northern China. His allies included the northern warlord Feng Yuxiang, the Guangxi Clique led by Li Zongren, and the left-leaning Kuomintang faction led by Wang Jingwei. While Feng and Chiang's armies were annihilating each other, Yan marched virtually unopposed through Shandong and captured the provincial capital of Jinan in June 1930. After those victories, Yan attempted to forge a new national government, with himself as president, by calling an "Enlarged Party Conference." Under his plan, Yan was to be president, and Wang was to serve as his prime minister. The conference attempted to draft a national constitution and involved the participation of numerous high-ranking Chinese militarists and politicians from among Chiang's rivals. The deliberations were interrupted by Chiang, who decisively defeated Feng's armies, invaded Shandong, and virtually annihilated Yan's army. When the governor of Manchuria, Zhang Xueliang, publicly declared his allegiance to Chiang, whose support Zhang required to contest the Russians and Japanese, Yan fled to Dalian in the Japanese-held Kwantung Leased Territory and returned to an unconquered Shanxi only after he had made peace with Chiang in 1931.[4][14][17] During the Central Plains War, the Kuomintang encouraged Muslims and Mongols to overthrow both Feng Yuxiang and Yan.[18] Chiang's defeat of Yan and Feng in 1930 is considered the end of China's Warlord Era.

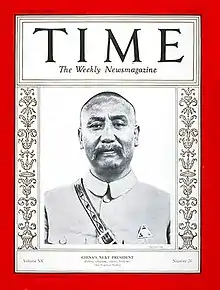

The events between 1927 and 1931 are best explained as the strategies of warlords accustomed to the constantly-shifting chaotic alliances that had characterized Chinese politics since the breakdown of the central government a decade earlier. The main causes of Yan's defeat were the low population and the lack of development in the areas that he had under his control, which made him incapable of fielding a large and well-equipped army similar to the ones commanded by Chiang at the time.[14] Yan was also unable to match the quality of leadership in Chiang's officer corps and the prestige that Chiang and the Nationalist Army had at the time.[19] Before Chiang's armies defeated Feng and Yan, Yan Xishan appeared on the cover of TIME Magazine, with the subtitle "China's Next President."[20] The attention given to him by foreign observers in that period and the support and assistance that he had secured from other high-profile Chinese statesmen implied that there was a credible expectation that Yan would lead a central government if Chiang failed to defeat Yan's alliance.

Return to Shanxi

Yan returned to Shanxi only through a complex effort of intrigue and politicking. Much of Chiang's failure to immediately and permanently eject Yan or his subordinates from Shanxi was largely from the influence of Zhang Xueliang and the Japanese, who were anxious to prevent the extension of Chiang's authority into Manchuria. In Yan's absence, the civil government of Shanxi ground to a halt, and the various military leaders of Shanxi struggled with one another to fill the vacuum, which forced Chiang's government to appoint Shanxi's leaders from among Yan's subordinates. Although he did not immediately declare his return to provincial politics, Yan returned to Shanxi in 1931 with the support and protection of Zhang. That move was not protested by Chiang because of his involvement in suppressing the forces of Li Zongren, who had marched up to northern Hunan from his base in Guangxi in support of Yan.[21]

Yan remained in the background of Shanxi politics until the Nanjing government's failure to resist the Japanese takeover of Manchuria after the Mukden Incident gave Yan and his followers an opportunity to informally overthrow the Kuomintang in Shanxi. On 18 December 1931, a group of students, supported and perhaps orchestrated by officials loyal to Yan, gathered in Taiyuan to protest the Nanjing government's policy of not fighting the Japanese. The demonstration became so violent that Kuomintang police fired into the crowd. The public outrage that the "Massacre of December Eighteenth" generated was strong enough to give Yan's officials a pretext to expel the Kuomintang from the province on the grounds of public safety. After that event, the Kuomintang ceased to exist in Shanxi except as a dummy organization whose members were more loyal to Yan than to Chiang.[22]

Future difficulties in securing the loyalty of other Chinese warlords across China, the ongoing civil war with the Communists, and the ongoing threat of Japanese invasion motivated Chiang to let Yan retain the title of Pacification Commissioner in 1932, and he appointed Yan to the central government's Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission. In 1934, Chiang finally flew to Taiyuan, where he praised Yan's administration in return for Yan's public support for Nanjing. By publicly praising Yan's government, Chiang in effect admitted that Yan remained the undisputed ruler of Shanxi.[23]

Subsequent relationship with Nationalist government

After 1931, Yan continued to give nominal support to the Nanjing government while he maintained de facto control over Shanxi by alternatively co-operating with and fighting against Communist agents active in his province. Although he was not an active participant, Yan supported the 1936 Xi'an Incident in which Chiang was arrested by Nationalist officers, led by Zhang Xueliang and Yang Hucheng and released only when he agreed to make peace with the Communists and form the united front to resist the impending Japanese invasion of China. In his correspondence with Zhang Xueliang in 1936, Yan indicated that the growing rift between him and Chiang was because of Yan's anxieties over the potential for a Japanese invasion and a concern for the subsequent fate of China and because Yan was not convinced of the correctness of focusing China's resources on anti-Communist campaigns.[6] During the Xian Incident itself, Yan actively involved himself in the negotiations by sending representatives to prevent Chiang's execution and the civil war that Yan believed would follow and to push for a united front to resist the Japanese invasion of China that Yan believed was imminent.[24]

The financial relationship between Shanxi and the central government remained complicated. Yan was successful in creating a complex of heavy industries around Taiyuan but neglected to publicize the extent of his success outside of Shanxi, probably to deceive Chiang. Despite his measured successes in modernizing the industry of Shanxi, Yan repeatedly petitioned the central government for financial assistance to extend the local railroad, and for other reasons, but his requests were usually denied. When Yan refused to send taxes collected from the trade of salt, produced in Shanxi's public factories, to the central government, Chiang retaliated by flooding the market of northern China with so much salt, produced around coastal China, that the price of salt in China's northern provinces dropped extremely low. Those artificially low salt prices made neighboring provinces virtually stop purchasing Shanxi salt altogether. In 1935, Chiang's announcement of a "five-year plan" to modernize Chinese industry was perhaps inspired by the successes of the "Ten-Year Plan" that Yan had announced several years earlier.[25]

Public policies

In Shanxi, Yan implemented numerous successful reforms in an effort to centralize his control over the province. Although embracing the traditional values of the landed gentry, he denounced their "oppression" of the peasantry and took steps to initiate land reform and weaken the power of landowners over the populace in the countryside. The reforms also weakened potential rivals in his province and benefited Shanxi farmers.[1]

Yan attempted to develop his army as a locally recruited force, which cultivated a public image of being servants, rather than masters, of the people. He developed an all-encompassing idiosyncratic ideology (literally "Yan Xishan Thought") and disseminated it by sponsoring a network of village newspapers and traveling dramatic troupes. He co-ordinated dramatic public meetings in which participants confessed their own misdeeds and/or denounced those of others. He devised a system of public education, producing a population of trained workers and farmers literate enough to be indoctrinated without difficulty. The early date by which Yan devised and implemented the reforms, during the Warlord Era, contradicts later claims that these reforms were modeled on Communist programs and not vice versa.[2]

Military policies

When Yan returned from Japan in 1909, he was a firm proponent of militarism and proposed a system of national conscription along German and Japanese lines. Germany's defeat during World War I and Yan's defeat in Henan in 1919 caused him to reassess the value of militarism as a way of life. He then decreased the size of the army until 1923 to save money until a rumor circulated that rival warlords were planning on invading Shanxi. Yan then introduced military reforms designed to train a rural militia of 100,000 men, along the lines of Japanese and American reserves.[26]

Yan attempted via conscription to create a civilian reserve, which would become the foundation of society in Shanxi. His troops were perhaps the only army in the Warlord era drawn exclusively from the province in which it was stationed, and because he insisted for his soldiers to perform work to improve Shanxi's infrastructure, including road-maintenance and assisting farmers, and because his discipline ensured that his soldiers actually paid for anything that they took from civilians, the army in Shanxi enjoyed much more popular support than most of his rivals' armies in China.[19]

Yan's officer corps was drawn from Shanxi's gentry and given two years of education at government expense. Despite efforts to subject his officers to a rigorous Japanese-style training regimen and to indoctrinate them in Yan Xishan Thought, his armies never proved to be especially well-trained or disciplined in battle. In general, Yan's military record is not considered positive (he had more defeats than victories) and it is unclear whether his officer corps either understood or sympathized with his objectives or entered his service solely in the interests of achieving prestige and a higher standard of living. Yan built an arsenal in Taiyuan that for the entire period of his administration remained the only center in China that could produce field artillery. The presence of the arsenal was one of the main reasons for Yan maintaining Shanxi's relative independence.[19] While not particularly effective fighting rival warlords, Yan's army was successful in eradicating banditry in Shanxi, which allowed him to maintain a relatively-high level of public order and security.[27] Yan's successes in eradicating banditry in Shanxi included his co-operation with Yuan Shikai to defeat Bai Lang's remnant rebels after the failed 1913-1914 Bai Lang Rebellion.

Attempts at social reform

Yan went to great lengths to eradicate social traditions that he considered antiquated. He insisted for all men in Shanxi to abandon their Qing-era queues and gave to police instructions to clip off the queues of anyone still wearing them. In one instance, Yan lured people into theatres to have his police systematically cut the hair of the audience.[27] He attempted to combat widespread female illiteracy by creating in each district at least one vocational school in which peasant girls could be given a primary-school education and taught domestic skills. After Kuomintang military victories in 1925 generated great interest in Shanxi for the Nationalist ideology, including women's rights, Yan allowed girls to enroll in middle school and college, where they promptly formed a women's association.[26]

Yan attempted to eradicate the custom of foot binding by threatening to sentence men who married women with bound feet and mothers who bound their daughters' feet to hard labor in state-run factories. He discouraged the use of the traditional lunar calendar and encouraged the development of local Boy Scout organizations. Like the Communists, who later succeeded Yan, he punished habitual lawbreakers to "redemption through labour" in state-run factories.[27]

Attempts to eradicate opium use

In 1916, at least 10% of Shanxi's 11 million people were addicted to opium, and Yan attempted to eradicate opium use in Shanxi after he came to power. At first, he dealt with opium dealers and addicts severely by throwing addicts in prison and exposing them and their families to public humiliation. After 1922, partly because of public opposition to harsh punishment, Yan abandoned punishing addicts in favor of attempting to rehabilitate them, pressuring individuals through their families, and constructing sanitariums designed to slowly cure addicts of their addictions.[28]

Yan's attempts to suppress the opium trade in Shanxi were largely successful, and the number of opium addicts in the province had been reduced by 80% by 1922. In the absence of efforts by other warlords to combat opium production and trade, Yan's efforts to combat opium use only increased the price of opium so much that narcotics of all kinds were drawn into Shanxi from other provinces. Users often switched from opium to pills mixed from morphine and heroin, which were easier to smuggle and use. Because the most influential and powerful gentry in Shanxi were often the worst offenders, officials drawn from the privileged class of Shanxi seldom enforced Yan's decrees outlawing the use of narcotics and often evaded punishment themselves. Eventually, Yan was forced to abandon his efforts to suppress opium trafficking and attempted instead to establish a government monopoly on the production and the sale of opium in Shanxi.[28] Yan continued to complain about the availability of narcotics into the 1930s and after 1932 executed over 600 people caught smuggling drugs into Shanxi. The traffic persisted, but Yan's interests in opposing it were perhaps limited by a fear of provoking the Japanese, who manufactured most of the morphine and heroin available in China in their concession area in Tianjin and came to control much of the drug trade in northern China in the 1930s.[29]

Limitations of economic reforms

Yan's efforts to stimulate Shanxi's economy mostly consisted of state-led investment in a broad variety of industries, and he generally failed to encourage private investment and trade. Though gains were made to improve the economy of Shanxi, his efforts were limited by the fact that he himself had little formal training in economic or industrial theory. He also suffered from a lack of experienced, trained advisers capable of directing even moderately complicated tasks related to economic development. Because most of the educated staff to whom he had access to were solidly entrenched within the landed gentry of Shanxi, it is possible that many of his officials may have deliberately sabotaged his efforts for reform by preferring that the peasants working their fields continue their traditional cheap labour.[30]

Yan Xishan Thought

Throughout his life, Yan attempted to identify, formulate, and disseminate a comprehensive ideology that would improve the morale and loyalty of his officials and of the people of Shanxi. During his time of study in Japan, Yan became attracted to militarism and Social Darwinism, but he renounced them after World War I. Throughout the rest of his life, he identified with the position of most Chinese conservatives at the time: social and economic reform would progress from ethical reform, and the problems confronting China could be solved only by the moral rehabilitation of the Chinese people.[31] Believing that no single ideology existed to unify the Chinese people when he came to power, Yan attempted to generate an ideal ideology himself, and once boasted that he had succeeded in creating a comprehensive system of belief that embodied the best features of "militarism, nationalism, anarchism, democracy, capitalism, communism, individualism, imperialism, universalism, paternalism and utopianism."[32] Much of Yan's attempts to spread his ideology were through a network of semi-religious organizations, known as "Heart-Washing Societies."

Influence of Confucianism

Yan was emotionally attached to Confucianism by virtue of his upbringing, and he identified its values as a historically effective solution to the chaos and disorder of his time. He justified his rule via Confucian political theories and attempted to revive Confucian virtues as being universally accepted. In his speeches and writing, Yan developed an extravagant admiration for the virtues of moderation and harmony associated with the Confucian Doctrine of the Mean. Many of the reforms that Yan attempted were undertaken with the intention of demonstrating that he was a junzi, the epitome of Confucian virtue.[31]

Yan's interpretations of Confucianism were mostly borrowed from the form of Neo-Confucianism, which had been popular during the Qing dynasty. He taught that everyone had a capacity for innate goodness, but to fulfill that capacity people had to subordinate their emotions and desires to the control of their conscience. He admired the Ming dynasty philosophers Lu Jiuyuan and Wang Yangming, who disparaged knowledge and urged men to act on the basis of their intuition. Because Yan believed that human beings could achieve their potentials only through intense self-criticism and self-cultivation, he established in every town a Heart-Washing Society, whose members gathered each Sunday to meditate and listen to sermons based on the themes of the Confucian classics. Everyone at the meetings was supposed to rise and confess aloud his misdeeds of the past week, inviting criticism from the other members.[33]

Influence of Christianity

Yan attributed much of the West's vitality to Christianity and believed that China could resist and overtake the West only by generating an ideological tradition that was equally inspiring. He appreciated the efforts of missionaries, mostly Americans who maintained a complex of schools in Taigu, to educate and modernize Shanxi. He regularly addressed the graduating classes of the schools but was generally unsuccessful in recruiting the students to serve his regime. Yan supported the indigenous Christian church in Taiyuan and at one time seriously considered using Christian chaplains in his army. His public support of Christianity waned after 1925, when he failed to come to the defense of Christians during the anti-foreigner and anti-Christian demonstrations that polarized Taiyuan.[34]

Yan deliberately organized many features of his Heart-Washing Society on the Christian church, including ending each service with hymns praising Confucius. He urged his subjects to place their faith in a supreme being that he called "Shangdi" and justified his belief in Shangdi via the Confucian classics but described Shangdi in terms very similar to the Christian interpretation of God. Like Christianity, Yan Xishan Thought was permeated with the belief that accepting his ideology could make people become regenerated or reborn.[34]

Influence of Chinese Nationalism

In 1911, Yan came to power in Shanxi as a disciple of Chinese nationalism but subsequently came to view nationalism as merely another set of ideas that could be used to achieve his own objectives. He stated that the primary goal of the Heart-Washing Society was to encourage Chinese patriotism by reviving the Confucian church, which led foreigners to accuse him of attempting to create a Chinese version of Shinto.[35]

Yan attempted to moderate some aspects of Sun Yat-sen's ideology that he viewed as potentially threatening to his rule. Yan altered some of Sun's doctrines before he disseminated them in Shanxi by formulating his own version of Sun's Three Principles of the People that replaced the principles of nationalism and democracy with the principles of virtue and knowledge. During the 1919 May Fourth Movement, when students in Taiyuan staged anti-foreign demonstrations, Yan warned that patriotism, like rainfall, was beneficial only in moderation.[35]

After the Kuomintang succeeded in forming a nominal central government in 1930, Yan encouraged Nationalist principles that he viewed as socially beneficial. In the 1930s, he attempted to set up in every village a "Good People's Movement" to promote the values of Chiang's New Life Movement. The values included honesty, friendliness, dignity, diligence, modesty, thrift, personal neatness, and obedience.[33]

Influence of socialism and communism

In 1931 Yan returned from his exile in Dalian impressed with the apparent successes of Soviet Union's first five-year plan and attempted to reorganize the economy of Shanxi by using Soviet methods, according to a local "Ten-Year Plan" that Yan himself developed.[36] Throughout the 1930s, Yan bluntly equated economic development with state control of industry and finance, and he had become successful in bringing most major industry and commerce under state control by the late 1930s.[37]

Yan's speeches after 1931 reflect an interpretation of Marxist economics, mostly drawn from Das Kapital, that he had gained in exile in Dalian. Following that interpretation, Yan attempted to change the economy of Shanxi to become more like that of the Soviets and inspired a scheme of economic "distribution according to labour". When the threat of Communists became a significant threat to Yan's rule, he defended them as courageous and self-sacrificing fanatics who were different from common bandits, contrary to Kuomintang propaganda and thought that their challenge must be met by social and economic reforms, which alleviated the conditions responsible for them.[38]

Like Karl Marx, Yan wanted to eliminate what he saw as unearned profit by restructuring Shanxi's economy to reward only those who worked. Unlike Marx, Yan reinterpreted Communism to correct what he believed was Marxism's chief flaw: the inevitability of class warfare. Yan praised Marx for his analysis of the material aspects of human society but professed to believe that there was a moral and spiritual unity of mankind that implied that a state of harmony was closer to the human ideal than conflict. By rejecting economic determinism in favor of morality and free will, Yan hoped to create a society that would be more productive and less violent than he perceived communism to be and to avoid the exploitation and the human misery that he believed was the inevitable result of capitalism.[39]

Yan interpreted Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal as promoting socialism to combat the spread of communism. "The New Deal is an effective way of stopping communism," Yan said, "by having the government step in and ride roughshod over the interests of the rich." Yan then undertook a series of public works projects inspired by the New Deal to reduce unemployment in his own province.[40]

Extent of success

In spite of his efforts, Yan did not succeed in making Yan Xishan Thought widely popular in Shanxi, and most of his subjects refused to believe that his true objectives differed substantially from those of past regimes. Yan himself blamed the failure of his ideology to become popular on the faults of his officials by charging that they abused their power and failed to explain his ideas to the common people. In general, the officials of Shanxi misappropriated funds intended to be used for propaganda, attempted to explain Yan's ideas in language too sophisticated for the common people, and often behaved in a dictatorial manner that discredited Yan's ideology and failed to generate popular enthusiasm for his regime.[41]

Threats to rule

Early conflict with Japan

Yan did not come into serious conflict with the Japanese until the early 1930s. While he was in exile in Dalian in 1930, Yan became aware of Japanese plans to invade Manchuria and feigned collaboration with the Japanese to pressure Chiang Kai-shek into allowing him to return to Shanxi before warning Chiang of Japan's intent. Japan's subsequent success in taking Manchuria in 1931 terrified Yan, who stated that a major objective of his Ten-Year Plan was to strengthen Shanxi's defense against the Japanese. In the early 1930s, he supported anti-Japanese riots, denounced the Japanese occupation of Manchuria as "barbarous" and "evil," publicly appealed to Chiang to send troops to Manchuria, and arranged for his arsenal to arm partisans fighting the Japanese occupation in Manchuria.[42]

In December 1931, Yan was warned that after taking control of Manchuria, the Japanese would attempt to take control of Inner Mongolia by subverting Chinese authority in Chahar and Suiyuan. To prevent that, he took control of Suiyuan first, developed its large iron deposits (24% of all iron in China), and settled the province with thousands of soldier-farmers. When the Manchukuo Imperial Army, armed and led by the Japanese, finally invaded Chahar in 1935, Yan virtually declared war on the Japanese by accepting a position as "advisor" of the Suiyuan Mongolian Political Council, an organization created by the central government to organize opposition to the Japanese.[43]

The Japanese began promoting "autonomy" for northern China in the summer of 1935. Some high-ranking Japanese military officials believed that Yan and other warlords in the north were fundamentally pro-Japanese and would readily subordinate themselves to the Japanese in exchange for protection from Chiang. Yan was a particular target because of his education in Japan and his much-publicized admiration of the country's modernization. However, Yan published an open letter in September in which he accused the Japanese of desiring to conquer all of China over the next two decades. According to Japanese sources, Yan entered into negotiations with the Japanese in 1935 but was never very enthusiastic about "autonomy" and rejected their overtures when he realized that they intended to make him their puppet. Yan likely used the negotiations to frighten Chiang into using his armies to defend Shanxi since he was afraid that Chiang was preparing to sacrifice northern China to avoid fighting the Japanese. If those were Yan's intentions, they were successful since Chiang assured Yan that he would defend Shanxi with his army if it was invaded.[44]

Early conflict with Communists

Although Yan admired their philosophy and economic methods, he feared the threat posed by Communists almost as much as that of the Japanese. In the early 1930s, he observed that if it invaded Shanxi, the Red Army would enjoy the support of 70% of his subjects and readily be able to recruit one million men from among its most desperate citizens. He remarked that "the job of suppressing communism is 70% political and only 30% military, while the job of preventing its growth altogether is 90% political." To prevent a Communist threat to Shanxi, Yan sent troops to fight the Communists in Jiangxi and (later) Shaanxi, organized the gentry and village authorities into anti-corruption and anti-communist political organizations, and attempted (mostly unsuccessfully) to undertake a large-scale program of land reform.[45]

Those reforms did not prevent the spread of Communist guerrilla operations into Shanxi. Led by Liu Zhidan and Xu Haidong, 34,000 Communist troops crossed into southwestern Shanxi in February 1936. As Yan had predicted, the Communists enjoyed massive popularity; although they were outnumbered and ill-armed, they succeeded in occupying the southern third of Shanxi in less than a month. The Communists' strategy of guerrilla warfare was extremely effective against and demoralizing for Yan's forces, who repeatedly fell victim to surprise attacks. The Communists in Shanxi made good use of co-operation supplied by local peasants to evade and easily locate Yan's forces. When the reinforcements sent by the central government forced the Communists to withdraw from Shanxi, the Red Army escaped by splitting into small groups, which were actively supplied and hidden by local supporters. Yan himself admitted that his troops had fought poorly during the campaign. The Kuomingtang forces that remained in Shanxi expressed hostility to Yan's rule but did not interfere with his governance.[46]

Invasion by Mengguguo

In March 1936, Manchukuo troops occupying the province in Inner Mongolia of Chahar invaded northeastern Suiyuan, which Yan controlled. The Japanese-aligned forces seized the city of Bailingmiao in northern Suiyuan, where the pro-Japanese Inner Mongolian Autonomous Political Council maintained its headquarters. Three months later, the head of the Political Council, Prince De (Demchugdongrub), declared that he was the ruler of an independent Mongolia (Mengguguo), and organized an army with the aid of Japanese equipment and training. In August 1936, Prince De's army attempted to invade eastern Suiyuan but was defeated by Yan's forces under the command of Fu Zuoyi. After that defeat, Prince De planned another invasion while Japanese agents carefully sketched and photographed Suiyuan's defenses.[47]

To prepare for the imminent threat of Japanese invasion, which he felt after Suiyuan was invaded, Yan attempted to force all students to undergo several months of compulsive military training and formed an informal alliance with the Communists for the purpose of fighting the Japanese several months before the Xi'an Incident compelled Chiang to do the same. In November 1936, the army of Prince De presented Fu Zuoyi with an ultimatum to surrender. When Fu responded that Prince De was merely a puppet of "certain quarters" and requested him to submit to the authority of the central government, Prince De's Mongolian and Manchurian armies launched another more ambitious attack. Prince De's 15,000 soldiers were armed with Japanese weapons, supported by Japanese aircraft, and often led by Japanese officers. Japanese soldiers fighting for Mengguguo were often executed after their capture as illegal combatants since Mengguguo was not recognized as being part of Japan.[48]

In anticipation of the war, Japanese spies destroyed a large supply depot in Datong and carried out other acts of sabotage. Yan placed his best troops and most able generals, including Zhao Chengshou and Yan's son-in-law, Wang Jingguo, under the command of Fu Zuoyi. During the month of fighting that ensued, the army of Mengguguo suffered severe casualties. Fu's forces succeeded in retaking Bailingmiao on 24 November, and he was considering invading Chahar before he was warned by the Japanese Kwantung Army that doing so would provoke an attack by the Imperial Japanese Army. Prince De's forces repeatedly attempted to retake Bailingmiao, but that only provoked Fu into sending troops north, where he successfully seized the last of Prince De's bases in Suiyuan and virtually annihilated his army. After Japanese officers were found to be aiding Prince De, Yan publicly accused Japan of aiding the invaders. His victories in Suiyuan over Japanese-backed forces were praised by Chinese newspapers and magazines, other warlords, and political leaders, and many students and members of the Chinese public.[49]

Second Sino-Japanese War

During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), most regions of Shanxi were quickly overrun by the Japanese, but Yan refused to flee the province even after he had lost the provincial capital, Taiyuan. He relocated his headquarters to a remote corner of the province and effectively resisted Japanese attempts to completely seize Shanxi. During the war, the Japanese made no less than five attempts to negotiate peace terms with Yan and hoped that he would become a second Wang Jingwei, but Yan refused and stayed aligned with the Second United Front between the Nationalists and the Communists.

Alliance with Communists

After the failed attempt by the Chinese Red Army to establish bases in southern Shanxi in early 1936, the subsequent continued presence of Nationalist soldiers there, and the Japanese attempts to take Suiyuan that summer, Yan became convinced that the Communists were lesser threats to his rule than were either the Nationalists or the Japanese. He then negotiated a secret anti-Japanese "united front" with the Communists in October 1936 and, after the Xi'an Incident two months later, successfully influenced Chiang to enter a similar agreement with the Communists. After establishing his alliance with the Communists, Yan lifted the ban on Communist activities in Shanxi.[50] He allowed Communist agents working under Zhou Enlai to establish a secret headquarters in Taiyuan[51] and released Communists that he had been holding in prison, including at least one general, Wang Ruofei.[52]

Yan, under the slogan "resistance against the enemy and defense of the soil," attempted to recruit young patriotic intellectuals to his government to organize a local resistance to the threat of a Japanese invasion. By 1936, Taiyuan had become a gathering point for anti-Japanese intellectuals who had fled from Beijing, Tianjin, and Northeast China and readily co-operated with Yan, but he also recruited natives of Shanxi who lived across China regardless of their former political associations. Some Shanxi officials attracted to Yan's cause in the late 1930s later became important figures in the Chinese government, including Bo Yibo.[53]

Early campaigns

In July 1937, after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident had provoked the Japanese into attacking Chinese forces in and around Beijing, the Japanese sent a large number of warplanes and Manchurian soldiers to reinforce Prince De's army. That caused Yan to believe that a Japanese invasion of Shanxi was imminent and so he flew to Nanjing to communicate the situation to Chiang. Yan left his meeting in Nanjing with an appointment as commander of the Second War Zone, comprising Shanxi, Suiyuan, Chahar, and northern Shaanxi.[54]

After returning to Shanxi, Yan encouraged his officials to be suspicious of enemy spies and hanjian and ordered his forces to attack Prince De's forces in northern Chahar in the hope of surprising and overwhelming them quickly. The Mongolian and Manchu forces were quickly routed, and Japanese reinforcements attempting to force their way through the strategic Nankou pass suffered heavy casualties. Overwhelming Japanese firepower, including artillery, bombers, and tank, eventually forced Yan's forces to surrender Nankou, and Japanese forces then quickly seized Suiyuan and Datong. The Japanese began the invasion of Shanxi in earnest.[55]

As the Japanese had advanced southward into Taiyuan Basin, Yan attempted to impose discipline on his army by executing General Li Fuying and other officers guilty of retreating from the enemy. He issued orders not to withdraw or to surrender under any circumstances, vowed to resist Japan until the Japanese had been defeated, and invited his own soldiers to kill him if he betrayed his promise. In the face of continued Japanese advances, Yan apologized to the central government for his army's defeats, asked it to assume responsibility for the defense of Shanxi, and agreed to share control of the provincial government with one of Chiang's representatives.[56]

When it became clear to Yan that his forces might not be successful in repelling the Japanese, he invited Communist military forces to re-enter Shanxi. Zhu De became the commander of the Eighth Route Army active in Shanxi and was named the vice-commander of the Second War Zone, under Yan himself. Yan initially responded warmly to the re-entry of the arrival of Communist forces, who were greeted with enthusiasm by Yan's officials and officers. Communist forces arrived in Shanxi just in time to help defeat a decisively more powerful Japanese force attempting to move through a strategic mountain pass at the Battle of Pingxingguan. After the Japanese had responded to the defeat by outflanking the defenders and moving towards Taiyuan, the Communists avoided decisive battles and mostly attempted to harass Japanese forces and sabotage Japanese lines of supply and communication. The Japanese suffered but mostly ignored the Eighth Route Army and continued to advance towards Yan's capital. The lack of attention directed at their forces gave the Communists time to recruit and propagandize among the local peasant populations, who generally welcomed Communist forces enthusiastically, and to organize a network of militia units, local guerrilla bands, and popular mass organizations.[57]

Genuine Communist efforts to resist the Japanese gave them the authority to carry out sweeping and radical social and economic reforms, mostly related to land and wealth redistribution, which they defended by labeling those who resisted as hanjian. Communist efforts to resist the Japanese also won over Shanxi's small population of patriotic intellectuals, and conservative fears of resisting them effectively gave the Communists unlimited access to the rural population. Subsequent atrocities committed by the Japanese in the effort to rid Shanxi of Communist guerrillas aroused the hatred of millions in the Shanxi countryside, which caused the rural population to turn to the Communists for leadership against the Japanese. All of those factors explain how within a year of re-entering Shanxi, the Communists had taken control of most parts of Shanxi that were not firmly held by the Japanese.[58]

Fall of Taiyuan

By executing commanders guilty of retreating, Yan succeeded in improving the morale of his forces. During the Battle of Pingxingguan, Yan's troops in Shanxi successfully resisted numerous Japanese assaults, and the Eighth Route Army harassed the Japanese from the rear and along their flanks. Other units of Yan's army successfully defended other nearby passes. After the Japanese had successfully broken into the Taiyuan Basin, they continued to encounter ferocious resistance. At Yuanping, a single brigade of Yan's troops held out against the Japanese advance for over a week, which allowed reinforcements sent by the Nationalist government to take up defensive positions at the Battle of Xinkou. The Communist generals Zhu De and Peng Dehuai criticized Yan for what they called "suicidal tactics," but Yan was confident that the heavy losses suffered by the Japanese would eventually demoralize them and force them to abandon their effort to take Shanxi.[59]

During the Battle of Xinkou, the Chinese defenders resisted the efforts of Japan's elite Itakagi Division for over a month, despite Japanese advantages in artillery and air support. By the end of October 1937, Japan's losses had become four times greater than those suffered at Pingxingguan, with the Itakagi Division near defeat. Contemporary Communist accounts called the battle "the most fierce in North China," and Japanese military reports referred to the battle a "stalemate", one of the few setbacks that Japanese military planners admitted to in the first several years of the war. In an effort to save their forces at Xinkou, Japanese forces began an effort to occupy Shanxi from a second direction, in the east. After a week of fighting, Japanese forces captured the strategic Niangzi Pass and opened the way to capturing Taiyuan. Communist guerrilla tactics were ineffective in slowing down the Japanese advance. The defenders at Xinkou, realizing that they were in danger of being outflanked, withdrew southward, past Taiyuan, and left a small force of 6,000 men to hold off the entire Japanese army. A representative of the Japanese Army, speaking of the final defense of Taiyuan, said that "nowhere in China have the Chinese fought so obstinately."[60]

The Japanese suffered 30,000 dead, with an equal number wounded, in their effort to take northern Shanxi. A Japanese study found that the Battles of Pingxingguan, Xinkou, and Taiyuan had been responsible for over half of all the casualties suffered by the Japanese in North China. Yan himself was forced to withdraw after 90% of his army had been destroyed, including a large force of reinforcements that had been sent into Shanxi by the central government. Throughout 1937, numerous high-ranking Communist leaders, including Mao Zedong, lavished praise on Yan for waging an uncompromising campaign of resistance against the Japanese.[61]

Re-establishment of Yan's authority

Shortly before losing Taiyuan, Yan moved his headquarters to Linfen, in southwestern Shanxi. Japanese forces halted their advance to focus on combating Communist guerrilla units still active in their territory and communicated to Yan that they would exterminate his forces within a year but that he and his supporters would be treated with consideration if they severed relations with the central government and assisted the Japanese in suppressing the Communists. Yan responded by repeating his promise not to surrender until Japan had been defeated. Possibly because of the severity of his losses in northern Shanxi, Yan abandoned a plan of defense based on positional warfare and began to reform his army as a force capable of waging guerrilla warfare. After 1938, most of Yan's followers came to refer to his regime as a "guerrilla administration."[62]

In February 1938, Japanese forces invaded Linfen. Yan's forces, under the command of Wei Lihuang, put up a stiff defense at Lingshi Pass but were eventually forced to abandon the position when a Japanese column broke through a different pass and threatened Linfen from the east. Wei prevented the Japanese from seizing the strategic Zhongtiao Mountain Range, but the loss of Linfen and Lingshi forced Yan to withdraw with what remained of his army across the Yellow River, into Yichuan County, Shaanxi, which closely neighbored the Communists' base, the Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region.[63]

In the spring of 1938, the Japanese transferred many of their forces away from Shanxi, and Yan succeeded in re-establishing his authority by setting up a headquarters in the remote mountainous district of Qixian. The Japanese made several raids into southern Shanxi but withdrew after they had encountered heavy resistance. By 1938, Yan's tactics had evolved to resemble the guerrilla warfare practiced by Communist forces in other parts of Shanxi, and his defenses featured co-ordination with Communist forces and regular divisions of the Nationalists.[64]

Yan's alliance with the Communists eventually suffered, as tensions escalated between the Nationalists and the Communists in other parts of China. Yan himself eventually came to fear the rapid power and influence that Communist forces operating in Shanxi had quickly gained, and that fear caused him to become increasingly hostile to Communist agents and soldiers. Those tensions eventually led to the breakdown of his good relations with the Communists by October 1939. During the Nationalist 1939–1940 Winter Offensive, which was led by Yan, he was perceived to be intentionally weakening the Communist-dominated "Shanxi New Army" by sacrificing them as the vanguard. Yan accused the New Army leadership of replacing Kuomintang officers with Communists, seizing grain supply from his Shanxi Clique troops, and sabotaging the Nationalist-led Winter Offensive. In December 1939, those units rebelled against Yan in what is known as the Jin-Xi Incident. Both the Nationalists and the Communists sent in reinforcements in the subsequent conflict. By February 1940, the internal conflict had mostly ceased. Yan's "old" Shanxi Clique army maintained control of southern Shanxi, the Eighth Route Army took control of north-western Shanxi, and the central government forces loyal to Chiang took control of central Shanxi. Yan's forces continued to battle the Japanese throughout 1940 as part of an indecisive guerrilla campaign.[65]

Negotiations with Japanese

In 1940 Yan's friend, Ryūkichi Tanaka, became chief of staff of the Japanese First Army, which was stationed in Shanxi. After Yan's animosity with the Communists became apparent, Tanaka began negotiations with Yan in an effort to induce him to enter into an anti-Communist alliance with Japan. Yan agreed to send a high-level representative to meet with the Japanese and obtained permission from the central government to negotiate with them for an agreement to remove all troops from Shanxi in exchange for Yan's co-operation. Perhaps because the Japanese were unwilling to meet those demands, Yan withdrew from negotiations in December 1940, when Tanaka's superiors recalled him to Japan. Two months later the Japanese repeated their charge that Yan was a "dupe" of the Communists.[66]

In May 1941, Tanaka returned to Shanxi and reopened negotiations with Yan, despite a general resistance from other Japanese military leaders in Northern China. Tanaka returned to Tokyo in August 1941 to pave the way for talks between Yan and General Yoshio Iwamatsu, then the commander of the Japanese First Army in Shanxi. In the summer of 1942, Yan told the Japanese that he would aid them in their fight against the Communists if the Japanese withdrew a large part of their forces from Shanxi and provided his army with food, weapons, and CH$15 million of precious metals.[67]

When Iwamatsu sent his chief of staff, Colonel Tadashi Hanaya, to Qixian for the purpose of delivering what Yan demanded, Yan called the Japanese concessions inadequate and refused to negotiate with them. That refusal is variously explained as Yan's resentment over the arrogance of the Japanese, his conviction that they would lose the war in the Pacific after he had heard about the Battle of Midway, and/or the result of a translation error that convinced him that the Japanese were using the negotiations as a ploy to ambush and to attack him by surprise. The Japanese, in any case, believed that they had been intentionally misled and humiliated. Iwamatsu lost his command, and Hanaya was reassigned to the Pacific.[68]

After 1943, the Japanese began to negotiate with Yan clandestinely through civilian representatives (notably his friend Daisaku Komoto) in an effort to avoid being humiliated by him. Through Komoto's efforts, Yan and the Japanese came to observe an informal ceasefire, but the terms of the agreement are unknown. By 1944, Yan's troops were actively battling the Communists, possibly with the co-operation and the assistance of the Japanese. His relationship with Chiang also deteriorated by 1944, when Yan warned that the masses would turn to Communism if Chiang's government did not improve considerably. An American reporter who visited Shanxi in 1944 observed that Yan "was thought of not necessarily as a puppet but rather as a compromise between the extremes of the treason at Nanjing and national resistance at Chongqing" by the Japanese.[69]

Relationship with Japanese after 1945

After the surrender of Japan and the end of World War II, Yan Xishan was notable for his ability to recruit thousands of Japanese soldiers stationed in northwest Shanxi in 1945, including their commanding officers, into his army. He was known to have successfully used a variety of tactics to achieve those defections: flattery, face-saving gestures, appeals to idealism, and genuine expressions of mutual interest. If he was not completely successful, he sometimes resorted to "bribes and women." His tactics in both convincing the Japanese to stay and preventing them from leaving were highly successful, as the efforts of the Japanese were instrumental in keeping the area surrounding Taiyuan free from Communist control for the four years before the Communists won the Chinese Civil War.[70]

Yan was successful in keeping the presence of the Japanese from American and Nationalist observers. He was known for making shows of disarming Japanese, only to rearm them at night. In one instance, he disarmed several units of Japanese, had a reporter take a picture of the stacked weapons to show that he was following orders, and gave the weapons back to the Japanese. He once officially labelled a detachment of Japanese troops as "railway repair laborers" in public records before he sent them, fully armed, into areas without railway tracks but full of Communist insurgents.[70]

By recruiting the Japanese into his service in that manner, he retained both the extensive industrial complex around Taiyuan and virtually all of the managerial and technical personnel employed by the Japanese to run it. Yan was so successful in convincing surrendered Japanese to work for him that as word spread to other areas of Northern China, Japanese soldiers from those areas began to converge on Taiyuan to serve his government and army. At its greatest strength, the Japanese "special forces" under Yan totaled 15,000 troops, plus an officer corps that was distributed throughout Yan's army. Those numbers were reduced to 10,000 after serious American efforts to repatriate the Japanese were partially successful. By 1949, casualties had reduced the number of Japanese soldiers under Yan's command to 3,000. The leader of the Japanese under Yan's command, Imamura Hosaku, committed suicide on the day that Taiyuan fell to Communist forces.[71]

Chinese Civil War

After the end of the Pacific War, Yan's forces, including thousands of former Japanese troops, held out against the Communists during the Chinese Civil War for four years, until April 1949, after the Nationalist government had lost control of Northern China, which allowed the Communists to encircle and besiege his forces. The area surrounding the provincial capital of Taiyuan was the longest to resist Communist control.

Shangdang Campaign

The Shangdang Campaign was the first battle between Communist and Nationalist forces after World War II. It began as an attempt by Yan, who was authorized by Chiang, to re-assert control over southern Shanxi, where the Communists were known to be especially active. Meanwhile, Yan's former general, Fu Zuoyi, had captured several important cities in Inner Mongolia: Baotou and Hohhot. If both Yan and Fu had been successful, they would have cut off the Communist headquarters in Yan'an from their forces in Northeast China. The local commander, Liu Bocheng, later named one of China's "Ten Great Marshals, decided to direct his forces against Yan in order to prevent that from happening. Liu's political commissar was the 41-year-old Deng Xiaoping, who later became China's "paramount leader."[72]

The initial skirmishes of the campaign were fought on 19 August 1945, when Yan dispatched 16,000 troops under Shi Zebo to capture the city of Changzhi, in southeastern Shanxi. On 1 September, Liu arrived with 31,000 troops and encircled Changzhi. After initial engagements between Shi Zebo's and Liu Bocheng's forces, Shi barricaded his forces inside the regional center of Chengzhi. Liu's army occupied the area surrounding Chengzhi but was not able to take the city, which led to a stalemate.[72]

After it became clear that Liu's forces were in danger of being defeated, Yan sent 20,000 more troops, who were commanded by Peng Yubin, to reinforce Shi and break the siege. Liu responded by concentrating his forces against Peng and leaving only a screening force behind to carry out low-level suppression activities in Changzhi.[72] Most of the forces left behind in Changzhi were selected from a local 50,000-man irregular militia unit, which had been used by Liu mainly for logistical support.

Peng was initially successful in defeating Communist detachments, but his forces were eventually led into an ambush. He was killed, and his army quickly surrendered en masse. When Shi realized that he had no hope of relief, he attempted to break out and flee to Taiyuan on 8 October but was caught on open ground, ambushed, and forced to surrender on 10 October.[73] He was taken as a prisoner-of-war.

Although both forces suffered the same amount of dead or wounded (4,000 to 5,000) the Communists captured 31,000 of Yan's troops, who surrendered once they had fallen into those ambushes. After surrendering, most of Yan's forces were subjected to organized persuasion or coercion and eventually joined the Communists.[74] Most of the Communist casualties in the campaign occurred when they attempted to confront Peng's reinforcements in an orthodox battle, which allowed Yan's forces to target Liu's troops with their superior arms. After those tactics failed, Communist forces killed or captured both Shi's and Peng's forces by leading both of them into a series of well-orchestrated ambushes.

The Shangdang Campaign ended with the Communists being in firm control of southern Shanxi. Because the army fielded by Yan was much better supplied and armed, the victory allowed the local Communists to acquire far more arms than had previously been available to them, including, for the first time, field artillery. It is said that the victory in the Shangdang campaign altered the course of the ongoing Chongqing peace negotiations, which allowed Mao Zedong to act from a stronger negotiating position. Their victory in the Shangdang campaign boosted the long-term prestige of both Liu and Deng.[75] After the campaign, Liu left a small force behind to defend southern Shanxi and led most of his best units and captured equipment to confront the forces of Sun Lianzhong in the Pinghan Campaign.[76]

In 1946, Communist forces in Northwest China identified the capture of Yan's capital of Taiyuan as one of their main objectives, and throughout 1946 and 1947, Yan was constantly involved in efforts to defend the north and to retake the south.[77] Those efforts were only temporarily successful, and by the winter of 1947, his control of Shanxi had become restricted to the area of northern Shanxi adjacent to Taiyuan. Yan observed that the Communists were growing stronger and predicted that within six months, they would rule half of China. After losing southern Shanxi, Yan undertook preparations to defend Taiyuan to the death, perhaps in the hopes that if he and other anti-Communist leaders could hold out long enough, the United States would eventually join the war on their side and save his forces from destruction.[78]

Taiyuan Campaign

By 1948, Yan's forces had suffered a succession of serious military defeats by the Communists, lost control of southern and central Shanxi, and were surrounded on all sides by territory controlled by the Communists. Anticipating an assault on northern Shanxi, Yan prepared his armies by fortifying over 5,000 bunkers, constructed over the rugged natural terrain surrounding Taiyuan. The Nationalist 30th Army was airlifted from Xian to Taiyuan to fortify the city, which was protected by over 600 pieces of artillery. Yan repeatedly declared his intentions to die in the city during that period. The total number of Nationalist troops present in northern Shanxi by the fall of 1948 was 145,000.

To overcome the defenses, the Communist commander Xu Xiangqian developed a strategy of engaging positions on the outskirts of Taiyuan before the city itself was besieged. The first hostilities in the Taiyuan Campaign occurred on 5 October 1948. By 13 November, the Communists had succeeded in taking the area around the eastern side of Taiyuan. The Nationalists suffered serious setbacks when entire divisions defected or surrendered. In one case, a Nationalist division, led by Dai Bingnan, pretended to surrender but then arrested the Communist officers who entered Dai's camp to accept. Yan Xishan mistakenly believed the leader of the arrested group, Jin Fu, was the high-ranking Communist leader Hu Yaobang, who the Nationalists believed was active in the region. Yan airlifted the captured group to Chiang, who executed them after they had failed to produce important information. Dai himself was rewarded with a large amount of gold for his actions but was not allowed to be airlifted out of Taiyuan. After the city fell, he was captured, tried in a well-propagandized show trial, and publicly executed.

Between November 1948 and April 1949, a stalemate was reached, and there was little advancement by either side. Tactics used by the Communists during that time included psychological warfare, such as forcing relatives of the Nationalist defenders to the front to ask for the defenders' surrender. Those tactics were successful, as from 1 December 1948 to March 1949, over 12,000 Nationalist soldiers surrendered.

After major PLA victories in Hebei in late January 1949, the Communist armies in Shanxi were reinforced with additional troops and artillery. After that reinforcement, the total number of men under Liu's command exceeded 320,000, of which 220,000 were reserves. By the end of 1948, Yan Xishan had lost over 40,000 troops, but he attempted to supplement that number through large-scale conscription.

Yan Xishan himself, along with most of the provincial treasury, was airlifted out of Taiyuan in March 1949 for the express purpose of asking the central government for more supplies. He left behind Sun Chu as the commander of his military police force, with Yan's son-in-law, Wang Jingguo, in charge of most Nationalist forces. Overall command was delegated to Imamura Hosaku, the Japanese lieutenant-general who had joined Yan after World War II.[79]

Shortly after Yan had been airlifted out of Taiyuan, Nationalist planes stopped dropping food and supplies for the defenders for fear of being shot down by the advancing Communists.[79] The Communists, depending largely on their reinforcements of artillery, launched a major assault on 20 April 1949 and succeeded in taking all of the positions surrounding Taiyuan by 22 April. A subsequent appeal to the defenders to surrender was refused. On the morning of 22 April 1949, the Communists bombarded Taiyuan with 1,300 pieces of artillery, breached the city's walls, and initiated bloody street-to-street fighting for control of the city. At 10:00 a.m. on 22 April, the Taiyuan Campaign ended with the Communists taking complete control of Shanxi. The total Nationalist casualties amounted to all 145,000 defenders, many of whom were taken as prisoners-of-war. Imamura committed suicide, Sun was captured, and Wang was last seen being led away by the Communists. The Communists lost 45,000 men and an unknown number of civilian laborers whom they had drafted, all of whom had been killed or injured.[80]

Later life

Premier of Republic of China

In March 1949, Yan flew to the capital of Nanjing to ask the central government for more food and ammunition. He had taken most of the provincial treasury with him and did not return before Taiyuan had fallen to Communist forces. Shortly after arriving in Nanjing, Yan insinuated himself into a quarrel between the acting president of the Chinese Republic, Li Zongren, and Chiang Kai-shek, who had resigned from the presidency in January 1949. However, many officials and generals remained loyal to Chiang, who retained over US$200 million, which he did not allow Li to use to fight the Communists or to stabilize the currency. The ongoing power struggle between Li and Chiang seriously disrupted the larger effort to defend Nationalist territory from the Communist forces.[81]

Yan focused his efforts on attempting to promote greater co-operation between Li and Chiang. On one occasion, he broke down in tears when attempting, at Chiang's request, to convince Li not to resign. He repeatedly used the example of the loss of Shanxi and warned that the Nationalist cause was doomed unless Li and Chiang's relationship improved. Li eventually attempted to form a government, including Chiang's supporters and critics, with Yan as premier. Despite Yan's efforts, Chiang refused to allow Li access to more than a fraction of the wealth that Chiang had sent to Taiwan, and officers loyal to Chiang refused to follow Li's orders, which frustrated efforts to co-ordinate Nationalist defenses and to stabilize the currency.[82]

By late 1949, the Nationalists' position had become desperate. The currency issued by the central government rapidly declined in value until it became virtually worthless. Military forces loyal to Li attempted to defend Guangdong and Guangxi, and those loyal to Chiang attempted to defend Sichuan. Both forces refused to co-operate with each other, which eventually led to the loss of both regions. Yan's constant attempts to work with both sides led to being alienated from both Li and Chiang, who resented Yan for co-operating with either side. The Communists succeeded in taking all territory held on the mainland by the end of 1949 and so defeated both Li and Chiang. Li went into exile in the United States, while Yan continued to serve as Premier in Taiwan until 1950, when Chiang re-assumed the presidency.[83]

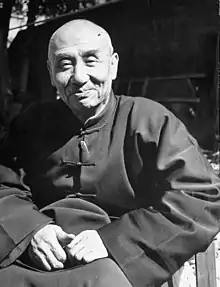

Retirement in Taiwan

Yan's final years were filled with disappointment and sadness. After following Chiang to Taiwan, he enjoyed the title of Chiang's "senior advisor" but in reality was utterly powerless. Chiang may have held a long-term grudge against Yan for the activities on behalf of Li in Guangdong. On more than one occasion, Yan requested permission to go to Japan, but he was not allowed to leave Taiwan.[84]

Yan was deserted by all but a handful of followers and spent most of his remaining years writing books on philosophy, history, and contemporary events, which he frequently had translated into English.[85] His late philosophical perspective has been described as "anti-communist and anti-capitalist Confucian utopianism." Several months before the Korean War Yan published a book, Peace or World War, in which he predicted that North Korea would invade South Korea, South Korea would be quickly overcome, the United States would intervene on the side of South Korea, and Communist China would intervene on the side of North Korea. All of those events later occurred over the course of the Korean War.[86]

Yan died in Taiwan on 24 May 1960.[85] He was buried in the Qixingjun region of Yangmingshan. For decades, Yan's residence and grave were cared for by a small number of former aides, who had accompanied him from Shanxi. In 2011, when the last of his aides turned 81 and was unable to care for the residence, the responsibility of maintaining the site was taken over by the Taipei City Government.[87]

Legacy

After the Chinese Civil War, Yan, like most other Nationalist generals who did not switch sides, was demonized by Communist propaganda.[88] It was not until after 1979, with new reforms in China, that he began to be viewed more positively and thus more realistically as a pragmatic anti-Japanese hero. The contributions by Yan during his period in office are beginning to be recognized by the current Chinese government.

Yan was sincere about his attempts to modernize Shanxi and achieved success in some regards. When he was forced out of Shanxi by the Communists, the province had become a major producer of coal, iron, chemicals, and munitions.[89] Yan's generous support for the Research Association for the Improvement of Chinese Medicine generated a body of teaching and publication in modern Chinese medicine that became one of the foundations of the national institution of modern traditional Chinese medicine that was adopted in the 1950s.[12] Throughout his rule, he attempted to promote social reforms that later came to be taken for granted but were highly controversial during his time, the abolition of foot binding, work for women outside the home, universal primary education, and the existence of peasant militias as a fundamental unit of the army. He was possibly the warlord most committed to his province in his era but was constantly challenged by his own dilettantism and the selfishness and the incompetence of his own officials.

Although Yan constantly spoke of the desirability and need for reforms, he remained until the 1930s too conservative to implement anything resembling the kind of reforms needed to successfully modernize Shanxi. Many of his attempts at reform in the 1920s had been attempted generations earlier, during the Tongzhi Restoration. The Qing dynasty reformers had found their reforms inadequate solutions to the problems of their time, and under the Model Governor, those reforms proved equally unsatisfactory. During the 1930s, Yan became increasingly open to radical social and economic policies, including wealth redistribution via graduated taxation, state-led industrialization, opposition to the money economy, an orientation towards functional (vs. "moral") education and the large-scale assimilation of Western technology. Despite his adoption of Soviet-style economic policies and increasingly-radical attempts at social reform, Yan was regarded as a "conservative" throughout his career, which suggests that the term "conservative" must be used carefully within the context of modern Chinese history.[91]

After Yan's time, Shanxi became the site of Mao Zedong's "model brigade" of Dazhai: a utopian communist scheme in Xiyang County that was supposed to be the model for all other peasants in China to emulate. If the people of Dazhai were especially suited for such an experiment, it is possible that decades of Yan's socialist indoctrination may have prepared the people of Shanxi for Communist rule. After the death of Mao, the experiment was discontinued, and most peasants reverted to private farming.

See also

- An Chang-nam, Yan Xishan's flight school principal from 1926 to 1930

- Eighth Route Army

- History of the Republic of China

- List of Warlords

- National Revolutionary Army

- Shang Zhen

- Shanxi clique

References

Citations

- Gillin The Journal of Asian Studies 289

- Gillin The Journal of Asian Studies 290

- Gillin The Journal of Asian Studies 291

- Wang 399

- Gillin The Journal of Asian Studies 292

- Spence 406

- Gillin Warlord 18

- Gillin The Journal of Asian Studies 302

- Harrison 62

- Gillin Warlord 22

- Andrews 171-172

- Harrison 61

- Harrison 63

- Gillin The Journal of Asian Studies 293

- TIME Magazine 24 December 1928. p.293

- Gillin Warlord 111

- TIME Magazine 29 September 1930

- Lin 22

- Gillin The Journal of Asian Studies 294

- TIME Magazine. 19 May 1930

- Gillin Warlord 118-122

- Gillin Warlord 122-123