Yosemite Valley Railroad

The Yosemite Valley Railroad (YVRR) was a short-line railroad that operated in California from 1907 to 1945, providing a new mode of travel and tourism for the region. It ran from Merced to the Yosemite National Park, but it did not extend to Yosemite Valley itself, as railroad construction was prohibited in the National Parks.[1] Tourists would disembark at the park boundary in El Portal, California and stay overnight at the Hotel Del Portal before taking a stagecoach to Yosemite Valley.

| |

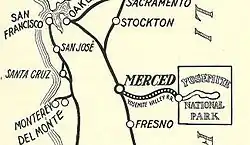

Route of Yosemite Valley Railroad. | |

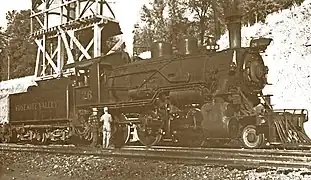

Engine Number 22 on the Merced Turntable | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Merced, California |

| Locale | Merced River, California |

| Dates of operation | 1902–1945 |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Electrification | none |

| Length | 80 miles (130 km) |

| Other | |

| Website | Yosemite Valley Railroad |

The YVRR replaced the stagecoach routes that had dominated travel and tourism in the area since the mid-1870s.[2] However, by the 1920s, the increasing popularity of automobiles had started to overtake the railroad in terms of tourist volume. By the 1940s, the completion of the Yosemite All-Year Highway and the decreased recreational passenger traffic due to World War II had all but eliminated demand for rail passenger service.

The YVRR also transported log cars for the Yosemite Lumber Company and limestone for the Yosemite Portland Cement Company as a freight carrier.[3]: 26, 66 The closure of these businesses in the early 1940s played a role in the railroad's decline, with the last regularly scheduled train running on August 24, 1945. Some structures and rolling stock of the YVRR are on display in El Portal, but little else remains of the railroad.

Among many notable passengers, the YVRR carried two presidents: William Howard Taft in October, 1909 and Franklin Roosevelt on July 15, 1938.

Background

The Yosemite Valley Railroad's construction marked a transformative moment for travel to Yosemite. Prior to its inception, the only means of transportation was a two-day stagecoach journey that was uncomfortable and dangerous due to the risk of stagecoach robbery.[4] The Southern Pacific's famous "Cannon-ball" stage from Raymond to Yosemite Valley was a marginally faster option, taking between twelve and fourteen hours to complete the trip. However, these trips were unaffordable for most, reserved only for the wealthy.[5]

Origins

The construction of the Yosemite Valley Railroad required a significant investment of capital and presented many engineering challenges.

Right-of-way

The Yosemite Valley Railroad ran from Merced, California to El Portal, which is the western boundary of Yosemite National Park. The route began in the city of Merced, where connections were made with the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe railways, and extended 78 miles to El Portal. Running the alongside the Merced River, this was the only feasible route for summer and winter travel to Yosemite Valley.

Though several companies had shown interest in constructing a rail line, it was a group of Oakland and San Francisco financiers who obtained the right-of-way for the most feasible route.[6] The Yosemite Valley Railroad hired Nathaniel C. Ray in 1902 as the chief engineer to build the railway, which required political knowledge as well as engineering talent. The northern boundary of Yosemite National Park was further north than it is today, and Congress prohibited railroads from entering any national park.[4] After several attempts to change the boundary, a bill was passed in 1905 that transferred certain lands from the park to the forest reserve, allowing the Yosemite Valley Railroad to obtain a permit to operate in the reserve in 1907.[7]

Construction

Tracklaying began on November 1, 1905, with the arrival of the first 10 carloads of rail.[8] To equip the railroad, the company purchased two locomotives from the Northern Pacific, a steam shovel, and a small narrow gauge work engine. During construction the company faced a shortage of labor, prompting them to advertise for 1000 workers at wages of $2.25 per day. The recruitment effort caused overcrowding in hotels and long lines at the employment office in Merced, prompting the company to expedite the hiring process with an arbitrary sign that read, "Bus leaves for camp each morning at 7 AM. Everybody can have a job. Don't ask questions!"[3]: 10 The workforce grew to about 1500 men in January 1906, but turnover was high due to the nature of the job.[3]: 11

The Yosemite Valley Railroad's first regularly scheduled train left from the Santa Fe depot, which was located six miles outside of town, on December 18, 1905. This marked the exact three-year anniversary of the railroad's incorporation. The company was complying with its state charter, which required five miles of the railroad to be in regular operation within three years of the charter's granting.[9] Tracks were completed to Merced Falls on March 4, 1906, and the formal opening of the railroad's regular schedule took place on May 25, 1906.[10] Regular service marked the end of the stagecoach business along the route.[11]

.jpg.webp)

Construction to El Portal ran through rough foothill and mountain country, and supplies and equipment were transported by pack horses, ropes, sleds, two-wheeled horse carts, wheelbarrows, and drags for grading. By May 1907, the rails had almost reached the boundary of Yosemite National Park, but the government refused to give up more right-of-way for the train to enter Yosemite Valley. Thus, the railroad built a stagecoach road that ran the six miles from El Portal into Yosemite Valley at a cost of $73,260.[12]

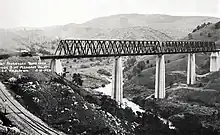

The entire roadbed for the Yosemite Valley Railroad was blasted out of solid rock, which required approximately 3,000,000 pounds of dynamite and powder and 285 miles of fuse. Three Howe truss bridges were built to cross the canyon's steep walls, located at Hopeton, Pleasant Valley, and Bagby, with a total of 65 smaller bridges and trestles along the route. The completed route had 63.5 miles of grades and 32.9 miles of curves with a maximum grade of 1-2%.[13] The main line had Bessemer rail weighing 70 pounds to the yard, and there were 505 curves, as well as 10,265 miles of yards and sidings.[3]: 15–16 A telephone and telegraph line was constructed along the route and completed on July 1, 1907, connecting Yosemite with the outside world.[14]

First full-length run

On May 15, 1907, the Yosemite Valley Railroad's first scheduled full-length run departed from Merced for El Portal, which was 80 miles away and had 12 passengers on board. Through connections in Merced, tourists could reach Yosemite by train in less than a day's journey from San Francisco (9 hours) and Los Angeles (16 hours).[15]

The train schedule allowed passengers to leave Merced at 2 p.m. and arrive at El Portal at 6 p.m. Passengers would have dinner and stay overnight at the tent hotel in El Portal before leaving for the Valley after breakfast the next morning, arriving at the Sentinel Hotel in the Valley before lunchtime. On their return, passengers would return in the afternoon, arrive at El Portal in time for dinner, stay overnight, and have breakfast before departing for Merced to catch the north and southbound trains on both Santa Fe and Southern Pacific.[16]

In 1907, the first year of operation, the number of recreation visits to Yosemite National Park increased by 30% to 7,102. By 1915, the annual number of recreation visits surpassed 30,000.[17]

Early operations

1900s

The Yosemite Valley Railroad experienced a successful beginning, with its business picking up just two months after its first run. It signed mail and express contracts, and its freight revenue from mines and quarries began to increase. The Southern Pacific gave up on its competing route and began advertising connections with the Yosemite run. The railroad's headquarters were in the new Merced depot, which had a roundhouse in use and a small station at El Portal. The four-story Hotel Del Portal at the eastern terminus attracted celebrities and politicians, including Senator Benjamin Tillman, Governor James Gillet, William Randolph Hearst, J.B. Duke, and John Muir.

The Yosemite Valley Railroad management improved operations and added new locomotives, passenger-express mail cars, and leased passenger cars. More than 50 people were making the trip daily. In December 1907, the railroad added its first winter excursion, allowing visitors to easily access the park year-round for the first time.[18] This was decades before the All-Year Highway was opened to automobile traffic in the 1940s.[19] The railroad carried 23,089 passengers, showing a book profit of $73,000 in its first year of operation.

In 1909, the Yosemite Valley Railroad established Pullman service, which became one of the heaviest traveled routes by 1910. The railroad partnered with the Selig Polyscope Company to produce a travelog about the Yosemite run that was shown all over the world.[20]

1910s

In 1910, the Yosemite Lumber Company was established, and the railroad played a crucial role in transporting the logs from the mountains to the sawmill at Merced Falls. Special standard gauge flat cars with bulkheads were necessary for the steep grades of the incline. The log cars ran from the woods down the incline and on the main line to the mill without reloading, saving labor costs. The lumbering venture doubled the railroad's freight income from $64,000 to $128,000.

In November 1913, the first automobile stage replaced the horse-drawn stages for the 14-mile route from El Portal to Yosemite Valley. The 25-passenger White Motor Company buses completed the trip in one hour and thirty-five minutes, compared to the four-hour journey required by the old horse stages.[21] By 1915, passenger and freight revenue continued to increase, and eighty percent of the passengers during the summer season were tourists from the Eastern United States.

In 1916, the Yosemite Valley Railroad leased the Hotel Del Portal and the stage line to the Desmond Park Service Company.[22] The new railroad brought increased visitation to the park, allowing the concessionaire to expand its offerings, including the luxurious Glacier Point Hotel built in 1917.[23]

This period was not without its setbacks. A disastrous fire on October 27, 1917, destroyed the Hotel Del Portal, causing an estimated loss of $100,000. The El Portal Inn, operated by a subsidiary of YVRR, replaced the Hotel Del Portal by the start of the next tourist season.[24]

Grand Central of the West

After World War I, the Yosemite Valley Railroad earned the nickname as the "Grand Central of the West", attracting tourists from all over the world to Yosemite National Park. Despite growing competition from buses and automobiles, the railroad continued to draw in visitors, including world leaders like Prince Axel of Denmark and King Albert of Belgium who traveled in private rail cars.[25][26]

In 1921, Yosemite claimed first place in attendance among national parks, surpassing Yellowstone National Park by a margin of approximately 10,000 visitors.[27] The Yosemite Valley Railroad had a particularly successful year, setting new records by carrying 2,000 people in a single day. The large number of Yosemite-bound specials, along with log trains running regularly to Merced Falls, allowed the railroad's payroll to grow to 350 employees. Despite significant fixed payments in 1923, 1925, and 1926, the railroad generated enough revenue to report a net profit. In 1925, passenger travel reached an all-time high, with over 85,000 people paying to ride the railway.[28]

To keep up with the growing popularity of private automobiles, the YVRR started offering auto ferrying services, building special platforms at Merced and El Portal to load cars for the trip to the Valley and back. This service proved especially popular with wealthy passengers and even attracted Hollywood movie stars, such as Buster Keaton, Fatty Arbuckle, Mae West, Mary Pickford, and Doug Fairbanks.[3]: 49

Exchequer Dam

In 1922, the Merced Irrigation District made the decision to construct the Exchequer Dam on the Merced River. This required the relocation of 16.7 miles of the main rail route, from Merced Falls nearly to Bagby Station.

The relocation involved erecting five steel bridges and two trestles, with the 1600 Barrett Bridge spanning the reservoir. The relocation was much more costly than originally estimated, due to the unstable rock conditions in the area. The four tunnels on the new line required timbering for nearly their entire length, and the bridge abutments used significantly more concrete than initially calculated. On April 18, 1926, the new line saw its first scheduled passenger train. A grand ceremony was held on June 23, 1926, to dedicate the dam itself. At 11 o'clock, President Coolidge pressed a button in the White House which set the power house machinery in motion.[29]

Decline

The Yosemite Valley Railroad experienced success with passenger revenue in its first 20 years, but the completion of a modern highway in 1926[30] and the increasing popularity of automobiles and buses caused a significant decline in revenue. At the same time, suspension of operations by the Yosemite Lumber Company in 1927 led to a fifty percent plunge in freight revenue.

The Great Depression

The stock market crash of 1929 and the depression worsened the situation, leading to the railroad's bankruptcy in 1935. To try and save the struggling company, the Yosemite Valley Railroad was publicly offered for sale as a "real railroad as a Christmas gift" for five million dollars in newspapers throughout California.[31]

The railroad was re-incorporated and showed a small gross profit between 1935 and 1937, thanks to increased freight traffic due to the reopening of the lumber mill. However, the railroad experienced unexpected events such as a flood that wiped out 30 miles of track along the Merced River.[32] A fire in Merced destroyed the tool shed and several passenger cars. These events caused significant damage and financial setbacks. To recover, the railroad required rehabilitation loans from the Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe to get the line back into operation.

In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt brought excitement to the Yosemite Valley Railroad by riding it and touring the Yosemite Valley, which included a lunch stop at Mariposa Big Trees Grove. The railroad picked up the President's party from the Southern Pacific in Merced and pulled the ten cars, including the President's private car, to El Portal using three freshly-painted, decorated locomotives. By evening, Roosevelt and his entourage were on their way back to Merced.[33]

Bankruptcy

In 1939, the Yosemite Valley Railroad experienced a doubling of passenger travel as the country began to recover from the depression. Despite running 79 special trains and nearly reaching $100,000 in gross profit, the amount was not enough to cover fixed costs. The trustees recognized the need for a refinancing plan, but the sale of the lumber company's timber rights to the government ended any hope of that. Consequently, the railroad requested permission to abandon operations from the Interstate Commerce Commission on October 25, 1944.[34] Due to decreased revenue, the railroad reduced its staff and service in 1944, and the last run of the Yosemite Valley Railway took place in 1945. The railroad was dismantled by the end of 1946, with most of the locomotives and equipment scrapped or sold.

Legacy

Today, the Yosemite Valley Railroad no longer exists, but some remnants can still be found. The El Portal Inn, which served as the railroad's terminus, burned down in 1932.[35] Some sections of the re-routed railbed were submerged when Exchequer Dam was expanded in the 1960s. However, a few of the railroad's tunnels still remain under Lake McClure and in Merced Canyon. The National Park Service relocated several surviving structures, such as the original hand-turned turntable, from Bagby to El Portal. At El Portal, Caboose No. 15, one of the few surviving pieces of rolling stock, is also on display. Locomotive 29, which was sold to a Mexican railroad after the Yosemite Valley Railroad's closure, is currently on static display in Veracruz, Mexico.[36]

The film Color of a Brisk and Leaping Day is based on the Yosemite Valley Railroad and 23-year old John McFadden's failed attempt to save it. The locations team revived the railroad on screen despite its 50-year dismantlement. The film was praised by the New York Times for its ability to capture natural beauty and evoke a vivid American past. It won the Cinematography Award at the 1996 Sundance Film Festival.[37]

Locomotive roster

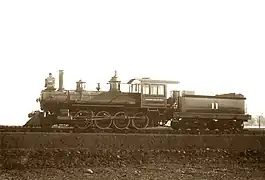

The Yosemite Valley Railroad used standardized motive power for its 38 years of operation. Its ten locomotives were all oil-burning, steam-powered Americans or Moguls, except for Number 11, which was an unusual 2-8-0 with a sloping firebox.[3]: 107 The first three engines were purchased secondhand and used in construction and regular service. The remaining seven locomotives were new from either Alco or Baldwin and remained in service until the railroad ceased operations. All engines initially had wooden cabs, but most were replaced with steel cabs, except for Numbers 11 and 20, which were sold before 1925.[3]: 107

With a history spanning nearly 60 years of activity, Number 21 is one locomotive that deserves special attention. Originally used for 25 years on the Wabash Railroad, it was later sold to the Yosemite Valley Railroad in 1906. Engineer Charlie Grant, who had a special attachment to Number 21, accompanied the locomotive to its new home on the Yosemite Valley Railroad, where he worked for 20 years before retiring with honors in 1926.[38] Despite its age, Number 21 continued to operate until the 1930s before being put on standby service, making it one of the most enduring classic 4-4-0 locomotives in American railroading history.[3]: 107

| Number | Wheel Configuration | Builder | Tractive Effort in Pounds | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 4-4-0 | Baldwin 1880 | 13,100 | The locomotive was originally built for the Northern Pacific Railroad as Number 32, later renumbered to 838. In October 1905, the Yosemite Valley Railroad purchased it and renumbered it to Number 1, then to 20. The locomotive was converted to run on oil and had electric lights added. In 1923, it was sold to a Mexican firm in Mazatlan and was later reported to be derelict on a beach in 1937.[39] |

| 21 | 4-4-0 | Wabash 1881 | 21,082 | The locomotive, which was previously known as Wabash 129, was purchased from Wabash in 1906 for $6,248.40. It was stationed at El Portal for emergency service in 1926 but stood derelict there for several years. Eventually, it was retired in 1932 and scrapped at Merced in 1946.[39] |

| 22 | 4-4-0 | ALCO 1907 | 18,720 | This locomotive was built by Alco in 1907 (Rogers) and purchased new for $13,589. In September 1945, the locomotive was sold to A.E. Perlman. It was later scrapped at Port Chicago in 1948.[39] |

| 23 | 4-4-0 | ALCO 1907 | 18,720 | This locomotive was purchased new for $14,735. Later, it was sold to Perlman. It was modified by M. & E.T. and utilized for switching chores. It was ultimately scrapped in the late 1940s.[39] |

| 25 | 2-6-0 | Baldwin 1925 | 28,600 | This locomotive was purchased new for $27,999.36. During World War II, it was leased by the Southern Pacific Railroad, and was eventually scrapped in the late 1940s.[39] |

| 26 (1st) | 2-8-0 | Altoona 1879 | 21,082 | This locomotive had a rich history of ownership before it came to be known as Yosemite Valley Railroad Number 26. It was originally Pennsylvania Railroad number 772, later becoming Bayfield and Western number 4, and then Northern Pacific number 4. In October 1905, the Yosemite Valley Railroad acquired the locomotive and designated it as number 11, before renumbering it to number 26 in 1906. It was eventually sold to Willette and Burr in June 1917. In 1937, it was stored in a shed near Niles, California and later scrapped in 1941.[39] |

| 26 (2nd) | 2-6-0 | ALCO 1924 | 28,600 | This locomotive was purchased new for $30,884. During World War II, it was leased by Southern Pacific Railroad, before being scrapped in the late 1940s.[39] |

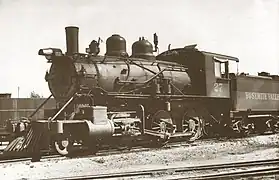

| 27 | 2-6-0 | Baldwin 1913 | 28,600 | This locomotive was purchased new for $17,340.18. Scrapped 1948.[39] |

| 28 | 2-6-0 | Baldwin 1917 | 28,600 | This locomotive was purchased new for $19,851. The locomotive was wrecked in July 1920 and was later rebuilt. It was eventually scrapped in the late 1940s.[39] |

| 29 | 2-6-0 | Baldwin 1922 | 28,600 | Sold to Ferrocarriles Unidos de Yucatán as 353, On static display in Veracruz and the only surviving YVRR locomotive.[39] |

- Yosemite Valley Railroad Locomotives

Engine 11

Engine 11 Engine 20

Engine 20 Engine 22

Engine 22 Engine 23

Engine 23 Engine 25

Engine 25 Engine 26

Engine 26 Engine 27

Engine 27 Engine 28

Engine 28 Engine 29

Engine 29

Further reading

- Johnston, Hank (January 1, 1971). Short Line to Paradise: The Story of the Yosemite Valley Railroad. Flying Spur Press; 2nd Edition. ISBN 978-0870460005

- Burgess, J.A. (2004). Trains to Yosemite. 1st ed. ISBN 978-1930013148

- Radanovich, L. (2010). Yosemite Valley Railroad. Arcadia Publishing. LCCN 2010-413057 OCLC 25684228

References

- "Can't Enter Valley. Interior Department Withstands Pressure from Railroads". Madera Mercury. Madera, California. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- "Reminiscences Are Aroused by Passing of the Stage Coach". Merced County Sun. Merced, California. May 25, 1906. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- Johnston, Hank. Railroads of the Yosemite Valley. Corona Del Mar, California: Trans-Anglo Book. ISBN 0-87046-055-2.

- Guest, Clayton J. (Second Quarter 1993). "Before Construction of the Yosemite Valley Railroad". For the Record. II (2).

- ""The Only Way" to Yosemite Valley, Nature's Wonderland". Merced County Sun. Merced, California. May 31, 1907. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- "Yosemite Railroads. A Southern Pacific Santa Fe Project that Looks like a Bluff". Mariposa Gazette. Mariposa, California. October 28, 1905.

- "Looks Like a Sure Go: Yosemite Valley Railroad Gets Rights to Government Has Granted it All Rights of Way and Station Sites". Stockton Record. Stockton, California. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- "Yosemite Railroad. Grading Commenced at Merced -- Ties and Rails Ordered". Mariposa Gazette. Mariposa, California. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- "Yosemite Train Running". Madera Mercury. Madera, California. December 23, 1905. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- "Opening of Yosemite Railroad. Merced People Have Declared June 6 a Holiday and Will Have Big Celebration". Hanford Sentinel. Hanford, California. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- "Reminiscences Are Aroused by Passing of the Stage Coach". Merced County Sun. Merced, California. May 25, 1906. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- "New Way to Yosemite Valley". San Francisco Call. San Francisco, California. May 16, 1907. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- Danley, L.E. (1908). "The New Yosemite Valley Railroad". The Railway Age. XLV (4): 110–112.

- FROM MERCED TO EL PORTAL: The Canyon Route to Yosemite. Foley's Yosemite Souvenir & Guide. 1907.

- ""The Only Way" to Yosemite Valley, Nature's Wonderland". Merced County Sun. Merced, California. May 31, 1907. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- "What Merced Needs". Merced County Sun. Merced, California. May 3, 1907. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- "Yosemite National Park Recreation Visits". Integrated Resource Management Applications (IRMA) Portal. National Park Service. 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- Strother, French (January 1909). "The Yosemite in Winter". Country Life in America.

- "Eagles Are Off to Yosemite: First Winter Excursions To Yosemite Valley Starts from Merced". Merced County Sun. Merced, California. December 6, 1907. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- "To Picture Yosemite: Moving Pictures Being Taken of Yosemite Valley Railroad for Use in Theaters All Over Country". Merced County Sun. Merced, California. June 11, 1909. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- "Auto Stage Runs into Yosemite Valley". Merced County Sun. Merced, California. November 21, 1913. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- "Management Changes at El Portal: Desmond Company to Assume Control of Yosemite Stage and Hotel at Terminal Town". Merced County Sun. September 1, 1916.

- "Yosemite: Then and Now: Encroaching Civilization - Visitor Services". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- "Early Travel to Yosemite is Heavy". Merced County Sun. Merced, California. April 1918. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- "Prince of Denmark Enjoying Visit in Yosemite". Merced County Sun. Merced, California. October 25, 1918. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- "Belgium King is Visiting Yosemite: Albert and Queen Go to Famous California Pleasure Ground for Two Days". San Jose Mercury-News. San Jose, California. October 16, 1919. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- "Yosemite is Most Popular of Parks". Enterprise. Riverside, California. October 10, 1921. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- "Dependable Service". Chronicle. Livingston. March 26, 1926. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- "Exchequer Dam and Power House are Dedicated". Chronicle. Livingston. June 25, 1926. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- "Road Opened to New Passage to Yosemite Park to be dedicated July 31 and Thrown Open to Public". San Pedro Daily News. San Pedro, California. July 10, 1926. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- "Real Railroad as Xmas Gift". Imperial Valley Press. Imperial Valley, California. November 26, 1935. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- Massey, Peter; Wilson, Jeanne (2006). Backcountry Adventures Northern California. Adler Publishing. p. 221. ISBN 1-93019-325-4.

- "Tracing the Yosemite Valley Railroad". Yosemite National Park. National Park Service. January 24, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- United Press, "Yosemite Railway Wants to Quit Line", The San Bernardino Daily Sun, San Bernardino, California, Thursday 26 October 1944, Volume 51, page 16.

- "Fire Destroys Inn at Yosemite Portal". Colusa Herald. Colusa, California. July 9, 1932. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- "Remaining YV Buildings and Equipment | Yosemite Valley Railroad".

- Maslin, Janet (March 23, 1996). "FILM FESTIVAL REVIEW;Trying to Rescue a Beloved Relic of the Past". The New York Times. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- Beebe, Lucius (1947). Mixed Train Daily. Berkeley, California: Howell-North.

- "Yosemite Railroad Company: Equipment Specifications: Locomotives". Memorable Places. Retrieved 2023-02-27.