Yusuf I of Granada

Abu al-Hajjaj Yusuf ibn Ismail (Arabic: أبو الحجاج يوسف بن إسماعيل; 29 June 1318 – 19 October 1354), known by the regnal name al-Muayyad billah (المؤيد بالله, "He who is aided by God"),[1] was the seventh Nasrid ruler of the Emirate of Granada on the Iberian Peninsula. The third son of Ismail I (r. 1314–1322), he was Sultan between 1333 and 1354, after his brother Muhammad IV (r. 1325–1333) was assassinated.

| Yusuf I | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| al-Muayyad billah | |||||||||

Dinar minted in Yusuf I's name | |||||||||

| Sultan of Granada | |||||||||

| Reign | 1333–1354 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Muhammad IV of Granada | ||||||||

| Successor | Muhammad V of Granada | ||||||||

| Born | 29 June 1318 The Alhambra, Granada | ||||||||

| Died | 19 October 1354 (aged 36) The Alhambra, Granada | ||||||||

| Spouse | Buthayna, Maryam/Rim[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||

| Issue Detail |

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Arabic | أبو الحجاج يوسف بن إسماعيل | ||||||||

| Dynasty | Nasrid | ||||||||

| Father | Ismail I of Granada | ||||||||

| Mother | Bahar | ||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||

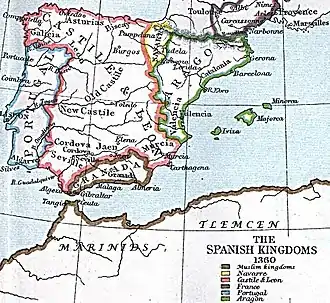

Coming to the throne at age fifteen, he was initially treated as a minor and given only limited power by his ministers and his grandmother Fatima. In February 1334, his representatives secured a four-year peace treaty with Granada's neighbours Castile and the Marinid Sultanate. Aragon joined in the treaty in May. After gaining more control of the government, in 1338 or 1340 he expelled the Banu Abi al-Ula family, who had masterminded the murder of his brother and had been the leaders of the Volunteers of the Faith—North African soldiers who fought for Granada. After the treaty expired, he allied himself with Abu al-Hasan Ali (r. 1331–1348) of the Marinids against Alfonso XI of Castile (r. 1312–1350). After winning a major naval victory in April 1340, the Marinid–Granadan alliance was decisively defeated on 30 October in the disastrous Battle of Río Salado. In its aftermath, Yusuf was unable to prevent Castile from taking several Granadan castles and towns, including Alcalá de Benzaide, Locubín, Priego and Benamejí. In 1342–1344, Alfonso XI besieged the strategic port of Algeciras. Yusuf led his troops in diversionary raids into Castilian territory, and later engaged the besieging army, but the city fell in March 1344. A ten-year peace treaty with Castile followed.

In 1349, Alfonso XI broke the treaty and invaded again, laying siege to Gibraltar. Yusuf was responsible for supplying the besieged port, and led counter-attacks into Castile. The siege was lifted when Alfonso XI died of the Black Death in March 1350. Out of respect, Yusuf ordered his commanders to not attack the Castilian army as they retreated from Granadan territories carrying their king's body. Yusuf signed a treaty with Alfonso's son and successor Peter I (r. 1350–1366), even sending his troops to suppress a domestic rebellion against the Castilian king, as required by the treaty. His relation with the Marinids deteriorated when he provided refuge for the rebellious brothers of Sultan Abu Inan Faris (r. 1348–1358). He was assassinated by a madman while praying in the Great Mosque of Granada, on the day of Eid al-Fitr, 19 October 1354.

In contrast to the military and territorial losses suffered during his reign, the emirate flourished in the fields of literature, architecture, medicine and the law. Among other new buildings, he constructed the Madrasa Yusufiyya inside the city of Granada, as well as the Tower of Justice and various additions to the Comares Palace of the Alhambra. Major cultural figures served in his court, including the hajib Abu Nu'aym Ridwan, as well as the poet Ibn al-Jayyab and the polymath Ibn al-Khatib, who consecutively served as his viziers. Modern historians consider his reign, and that of his son Muhammad V (r. 1354–1359, 1362–1391), as the golden era of the Emirate.

Early life

Abu al-Hajjaj Yusuf ibn Ismail was born on 29 June 1318 (28 Rabi al-Thani 718 AH) in the Alhambra, the fortified royal palace complex of the Nasrid dynasty of the Emirate of Granada. He was the third son of the reigning sultan, Ismail I, and a younger brother of the future Muhammad IV.[2] Ismail had four sons and two daughters, but Yusuf was the only child of his mother, Bahar. She was an umm walad (freed concubine) originally from the Christian lands, described as "noble in good deeds, chastity and equanimity" by Yusuf's vizier, the historian Ibn al-Khatib.[2][3] When Ismail was assassinated in 1325, he was succeeded by the ten-year old Muhammad, who ruled until he too was assassinated in 25 August 1333, when he was en route back to Granada after repulsing a Castilian siege of Gibraltar, jointly with the Marinids of Morocco.[4]

Ibn al-Khatib described the young Yusuf as "white-skinned, naturally strong, had a fine figure and an even finer character", with large eyes, dark straight hair and a thick beard. He further wrote that Yusuf liked to "dress with elegance", was interested in art and architecture, was a "collector of arms", and "had some mechanical ability".[5] Before his accession, Yusuf lived in his mother's house.[6]

Background

Founded by Muhammad I in the 1230s, the Emirate of Granada was the last Muslim state on the Iberian Peninsula.[7] Through a combination of diplomatic and military manoeuvres, the emirate succeeded in maintaining its independence, despite being located between two larger neighbours: the Christian Crown of Castile to the north and the Muslim Marinid Sultanate across the sea in Morocco. Granada intermittently entered into alliance or went to war with both of these powers, or encouraged them to fight one another, in order to avoid being dominated by either.[8] From time to time, the sultans of Granada swore fealty and paid tribute to the kings of Castile, an important source of income for Castile.[9] From Castile's point of view, Granada was a royal vassal, while Muslim sources never described the relationship as such. Muhammad I, for instance, on occasion declared his fealty to other Muslim sovereigns.[10]

Yusuf's predecessor, Muhammad IV, sought help from the Marinid Sultanate to counter a threat by an alliance of Castile and the powerful Granadan commander Uthman ibn Abi al-Ula, who supported a pretender to the throne in a civil war. In exchange for the Marinid alliance, he had to yield Ronda, Marbella and Algeciras. Subsequently, the Marinid–Granadan forces captured Gibraltar and fended off a Castilian attempt to retake it, before signing a peace treaty with Alfonso XI of Castile and Abu al-Hasan Ali of the Marinids the day before Muhammad IV's assassination.[11] While the actual killing of Muhammad IV was carried out by a slave named Zayyan, the instigators were Muhammad's own commanders, Abu Thabit ibn Uthman and Ibrahim ibn Uthman. They were the sons of Uthman ibn Abi al-Ula, who died in 1330, and his successors as the leaders of the Volunteers of the Faith, the corps of North Africans fighting on the Iberian Peninsula for Granada.[11][4][12] According to Ibn Khaldun, the two brothers decided to kill Yusuf due to his closeness to the Marinid Sultan Abu al-Hasan—their political enemy—while according to Castilian chronicles it was because of the friendly way he treated Alfonso XI at the conclusion of the siege.[11][13]

As a result of Muhammad's cessions to the Marinids and the taking of Gibraltar, the Marinids had sizeable garrisons and territories on traditionally Granadan lands in Al-Andalus (the Muslim-controlled part of the Iberian Peninsula). Their control of Algeciras and Gibraltar—two ports of the Strait of Gibraltar—gave them ability to move troops easily between North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula. The control of these ports and the waters surrounding them was also an important objective for Alfonso XI, who wanted to halt the North African intervention in the peninsula.[2]

Accession

The Nasrid dynasty of Granada had no specific rule of succession, and the sources are silent as to why Yusuf was chosen over Ismail's second son Faraj, who was a year older.[4][2] There are differing reports of where Yusuf was proclaimed and who selected him. According to the historians L. P. Harvey and Brian Catlos, who follow the report of the Castilian chronicles,[14][2] the hajib (chamberlain) Abu Nu'aym Ridwan, who was present at Muhammad IV's assassination, rode quickly to the capital Granada, arriving on the same day and, after consultation with Fatima bint al-Ahmar (Ismail's mother, and grandmother of Muhammad and Yusuf), arranged for the declaration of Yusuf as the new sultan.[15][14] The proclamation took place the next day, 26 August (14 Dhu al-Hijja 733 AH).[2] Another modern historian, Francisco Vidal Castro, writes that the declaration and the oath of allegiance took place in the Muslim camp near Gibraltar instead of in the capital, and that the instigators of the assassination, the Banu Abi al-Ula brothers, were the ones who proclaimed him.[2]

Coming to the throne at the age of fifteen, Yusuf was initially treated as a minor and, according to Ibn al-Khatib, his authority was limited to only "choosing the food to eat from his table".[16] His grandmother, Fatima, and the hajib Ridwan became his tutors and exercised some powers of government, together with other ministers. Upon his accession he took the laqab (honorific or regnal name) al-Mu'ayyad billah ("He who is aided by God"). The founder of the dynasty, Muhammad I, had taken a laqab (al-Ghalib billah, "Victor by the grace of God") but the subsequent sultans up to Yusuf did not adopt this practice. After Yusuf this was done by almost all of the Nasrid sultans.[2] According to the Castilian chronicles, Yusuf immediately requested the protection of Abu al-Hasan, his late brother's ally.[17]

Political and military events

Early peace

The peace that Muhammad IV secured after the siege of Gibraltar was, by the principles of the time, rendered void by his death, and representatives of Yusuf met with those of Alfonso XI and Abu al-Hasan Ali.[2][18] They signed a new treaty with a four-year duration at Fez, the capital of the Marinid Sultanate, on 26 February 1334. Like previous treaties, it authorised free trade between the three kingdoms, but, unusually, it did not include payments of tribute from Granada to Castile. Marinid ships were to be given access to Castilian ports, and the Marinid Sultan Abu al-Hasan promised not to increase his garrisons on the Iberian Peninsula—but he could still rotate them.[19] The latter condition was favourable not only to Castile but also to Granada, which was wary of possible expansionism by the larger Marinid Sultanate into the peninsula.[2] Alfonso IV of Aragon (r. 1327–1336) agreed to join the treaty in May 1334 and signed his own agreement with Yusuf on 3 June 1335. After Alfonso IV's death in January 1336, his son Peter IV (r. 1336–1387) renewed the bilateral Granadan–Aragonese treaty for five years, ushering in a period of peace between Granada and all its neighbours.[20]

With the treaty in place, the monarchs redirected their attentions elsewhere: Alfonso XI cracked down on his rebellious nobles, while Abu al-Hasan waged war against the Zayyanid Kingdom of Tlemcen in North Africa.[20] During these years, Yusuf acted against the Banu Abi al-Ula family, the masterminds of Muhammad IV's assassination. In September 1340 (or 1338), Abu Thabit ibn Uthman was removed from his post as the overall Chief of the Volunteers and replaced by Yahya ibn Umar of the Banu Rahhu family. Abu Thabit was expelled along with his three brothers and the entire family to the Hafsid Kingdom of Tunis.[2][21] Harvey comments that "[b]y the standards of acts of revenge in those days [...] this was quite restrained", probably because Yusuf did not want to unnecessarily create tensions with the North African volunteers.[21]

Marinid–Granadan war against Castile

In the spring of 1339, after the expiration of the treaty, hostilities recommenced with Marinid raids into the Castilian countryside. Confrontations ensued between Castile on one side and the two Muslim kingdoms on the other. Granada was invaded by Castilian troops led by Gonzalo Martínez, Master of the Order of Alcántara, who raided Locubín, Alcalá de Benzaide and Priego. In turn, Yusuf led an army of 8,000 in besieging Siles, but was forced to lift the siege by the forces of the Master of the Order of Santiago, Alfonso Méndez de Guzmán.[22][lower-alpha 2]

The personal rivalry between Martínez and de Guzmán appears to have caused the former to defect to Yusuf, but he was soon captured by Castilian forces, hanged as a traitor and his body burned. The Marinid commander on the peninsula, Abu Malik Abd al-Wahid, son of Abu al-Hasan, died during a battle with Castile on 20 October 1339, but Marinid forces continued to ravage the Castilian frontiers until they were defeated at Jerez.[24] At the same time, Nasrid forces achieved military successes, including the conquest of Carcabuey.[2]

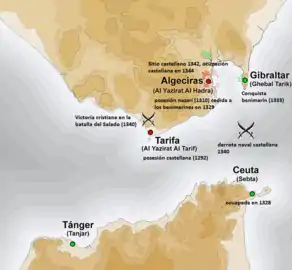

In autumn 1339, the Aragonese fleet under Jofre Gillabert tried to land near Algeciras but was driven away after their admiral was killed.[25] On 8 April 1340, a major battle took place off Algeciras between the Castilian fleet under Alfonso Jofré Tenorio and a larger Marinid–Granadan fleet under Muhammad al-Azafi, resulting in a Muslim victory and the death of Tenorio.[26][27] The Muslim fleet captured 28 galleys out of the 44 in the Castilian fleet, as well as 7 carracks. Abu al-Hasan saw the naval victory as a harbinger for the conquest of Castile.[26] He crossed the Strait of Gibraltar with his army, including siege engines, his wives and his entire court. He landed in Algeciras on 4 August, was joined by Yusuf, and laid siege to Tarifa, a Castilian port on the Strait, on 23 September.[28]

Alfonso XI marched to relieve Tarifa, joined by Portuguese troops led by his ally, King Afonso IV of Portugal (r. 1325–1357).[29] They arrived five miles (eight kilometres) from Tarifa on 29 October, and Yusuf and Abu al-Hasan moved to meet them.[30] Alfonso XI commanded 8,000 horsemen, 12,000 foot soldiers and an unknown number of urban militia, while Afonso IV had 1,000 men.[29] The Muslim strength is unclear: contemporary Christian sources claimed an exaggerated 53,000 horsemen and 600,000 foot soldiers,[31] while modern historian Ambrosio Huici Miranda in 1956 estimated 7,000 Granadan troops and 60,000 Moroccans. Crucially, the Christian knights had much better armour than the more lightly equipped Muslim cavalry.[29]

Battle of Río Salado

.jpg.webp)

The resulting Battle of Río Salado (also known as the Battle of Tarifa), on 30 October 1340, was a decisive Christian victory. Yusuf, who wore a golden helmet in the battle, fled the field after a charge by the Portuguese troops. The Granadan contingent initially defended itself and was about to defeat Afonso IV in a counterattack, but was routed when Christian reinforcements arrived, leaving their Marinid allies behind. The Marinids too were routed in the main battle against the Castilians, which lasted from 9:00 a.m. to noon.[32] Harvey opined that the key to the Christian victory—despite their numeric disadvantage—was their cavalry tactics and superior armour. Muslim tactics—which focused on lightly armoured, highly mobile cavalry—were well suited for open battle, but in the relatively narrow battlefield of Río Salado the Christian formation of armoured knights attacking in a well-formed battle line had a decisive advantage.[29]

In the aftermath of the battle, the Christian troops pillaged the Muslim camp, and massacred the women and children, including Abu al-Hasan's queen, Fatima, the daughter of King Abu Bakr II of Tunis—to the dismay of their commanders, who would have preferred to see her ransomed.[32] Numerous royal persons and nobles were captured, including Abu al-Hasan's son, Abu Umar Tashufin.[33] Among the fallen were many of Granada's intellectuals and officials.[2] Yusuf retreated to his capital through Marbella. Abu al-Hasan marched to Gibraltar, sent news of victory back home to prevent any rebellion in his absence, and crossed the Strait to Ceuta the same night.[33]

Various Muslim authors laid the blame on the Marinid Sultan, with Umar II of Tlemcen saying that he "humiliated the head of Islam and filled the idolaters with joy",[32] and al-Maqqari commenting that he allowed his army to be "scattered like dust before the wind".[33] Yusuf appeared to not have been blamed, and continued to be popular in Granada.[21] Alfonso XI returned victorious to Seville and paraded the Muslim captives and the booty taken by his army.[34] There was so much gold and silver that their prices as far away as Paris and Avignon fell by one sixth.[35]

After Río Salado

With the bulk of the Marinid forces retreating to North Africa, Alfonso XI was able to act freely against Granada.[12] He invaded the emirate in April 1341, feigning an attack against Málaga. When Yusuf reinforced this western port—taking many men from elsewhere—Alfonso redirected his troops towards Alcalá de Benzaide, a major border fortress 30 miles (50 km) north of Granada, whose garrison had been reduced in order to reinforce Málaga.[36] The Castilian army started a siege and ravaged the surrounding countryside, not only taking food but also destroying vines—causing lasting damage to the local agriculture without any benefit to the attackers. In response, Yusuf moved to a strong position in Pinos Puente to block Castilian attempts to raid further into the rich plains surrounding the city of Granada. Alfonso XI extended the raids into more areas in order to tempt Yusuf to leave his position, but the Granadan army held its ground as the Castilians devastated the area surrounding Locubín and Illora.[37] As the siege progressed, Yusuf received Marinid reinforcements from Algeciras and moved six miles (ten kilometres) to Moclín. Neither side was willing to risk a frontal attack, and Alfonso unsuccessfully tried to provoke Yusuf into an ambush.[38] With relief unlikely, the Muslim defenders of Alcalá offered to surrender the fortress in exchange for safe conduct, to which Alfonso agreed; the capitulation took place on 20 August 1341. Yusuf then offered a truce, but Alfonso demanded that he break his alliance with the Marinids, which Yusuf refused to do, and the war continued.[39][2]

Concurrently with the siege of Alcalá, Alfonso's troops also captured the nearby Locubín. In the weeks after the fall of Alcalá, the Castilians captured Priego, Carcabuey, Matrera and Benamejí.[36] In May 1342, a Marinid–Granadan fleet sailing in the Strait of Gibraltar was ambushed by Castilian and Genoese ships, resulting in a Christian victory, the destruction of twelve galleys and the dispersal of other vessels along the Granadan coast.[40]

Siege of Algeciras

Alfonso XI then targeted Algeciras, an important port on the Strait of Gibraltar which his father, Ferdinand IV, had failed to take in 1309–10. Alfonso arrived in early August 1342 and slowly imposed a land and sea blockade on the city.[41] Yusuf's army took to the field, joined by Marinid troops from Ronda, trying to threaten the besiegers from the rear or divert their attention. Between November 1342 and February 1343, it raided the lands around Écija, entered and sacked Palma del Río, retook Benamejí and captured Estepa.[2][42] In June, Yusuf sent his hajib, Ridwan, to Alfonso, offering payments in exchange for the lifting of the siege. Alfonso countered the offer by increasing the payment he would require.[2][43] Yusuf sailed to North Africa to consult with Abu al-Hasan and raise the money, but the payment from the Marinid Sultan was not enough. Despite the safe conduct given by Alfonso, Yusuf's galley was attacked by a Genoese ship in Alfonso's service, which tried to steal the gold. Yusuf's ships repulsed the attack; Alfonso apologised but did not take any action against the Genoese ship's captain.[44][45]

The Muslim defenders of Algeciras made use of cannons, one of the earliest recorded uses of this weapon in a major European confrontation—before their better-known use at the Battle of Crécy in 1346.[46][47][12] Alfonso's forces were augmented by crusading contingents from all over Europe, including from both France and England, which were at war. Among European nobles present were King Philip III of Navarre, Gaston, Count of Foix, the Earl of Salisbury and the Earl of Derby.[48]

On 12 December 1343, Yusuf crossed the Palmones River and engaged a Castilian detachment. This was reported in Castilian sources as a Muslim defeat. Early in 1344, Alfonso constructed a floating barrier, made of trees chained together, that stopped supplies from reaching Algeciras. With the hope of victory fading and the city on the verge of starvation, Yusuf began negotiations again.[45][49] He sent an envoy, named Hasan Algarrafa in Castilian chronicles, and offered the surrender of Algeciras if its inhabitants were allowed to leave with their movable property, in exchange for a fifteen-year peace between Granada, Castile and the Marinids. Despite being counselled to reject the offer, and instead to take Algeciras by storm and massacre its inhabitants, Alfonso was aware of the uncertain outcome of an assault when hostile forces were nearby. He agreed to Algarrafa's proposal, but requested that the truce be limited to ten years, which Yusuf accepted. Other than Yusuf and Alfonso, the treaty included Abu al-Hasan, Peter IV and the Doge of Genoa. Yusuf and Alfonso signed the treaty on 25 March 1344 in the Castilian camp outside Algeciras.[50][51]

Siege of Gibraltar and related events

War broke out again in Granada in 1349, when Alfonso declared that the peace treaty no longer prevented him from attacking Muslim territories because the Marinid Iberian territories were now controlled by Abu Inan Faris, Abu al-Hasan's son, who had rebelled and seized Fez the year before. In June or July 1349, his forces began the siege of Gibraltar, a port which had been captured by Ferdinand IV in 1309 before falling to the Marinids in 1333. Prior to the siege, Yusuf sent archers and foot soldiers to reinforce the town's garrison. In July, Alfonso was personally present among the besiegers, and in the same month he ordered his Kingdom of Murcia[lower-alpha 3] to attack Yusuf's Granada.[53] Despite Yusuf's protests, Peter IV sent an Aragonese fleet to assist the siege, even though in order to respect the peace treaty with Yusuf he instructed his men not to harm any subject of Granada.[54] With the Marinids unable to send help, the main responsibility for fighting Castile fell to Yusuf, who led his troops in a series of counter-attacks. During the summer of 1349 he raided the outskirts of Alcaraz and Quesada, and besieged Écija. In the winter he sent Ridwan to besiege Cañete la Real, which surrendered after two days.[2]

As the siege progressed, the Black Death (known in Spain as the mortandad grande), which had entered Iberian ports in 1348, struck the besiegers' camp. Alfonso persisted in the siege despite the urgings of his counselors. He became infected himself and died on either Good Friday 1350 (26 March) or the day before. The Castilian forces withdrew from Gibraltar, with some of the defenders coming out to watch.[55] Out of respect, Yusuf ordered his army and his commanders in the border regions not to attack the Castilian procession as it travelled with the King's body to Seville.[56] Alfonso was succeeded by his fifteen-year-old son, Peter I. Yusuf, Peter and Abu Inan of the Marinids concluded a treaty in 17 July 1350, which was to last until 1 January 1357. Trade was reopened between Granada and Castile (except for horses, arms and wheat), and captives were exchanged. In exchange for peace, Yusuf paid tribute to Peter and agreed to provide 300 light horsemen when requested, but Yusuf did not formally become Peter's vassal. Despite privately disliking Peter, Yusuf observed his treaty obligations: he sent 300 jinete cavalry—reluctantly, according to the historian Joseph O'Callaghan—to help the Castilian king suppress the rebellion of Alfonso Fernández Coronel in Aguilar, and refused to help the King's half-brother, Henry, when he attempted to start a rebellion against Peter from Algeciras.[57]

Yusuf and the Marinid princes

Abu al-Hasan tried unsuccessfully to regain the Marinid throne until his death in 1351. Two other challengers to Abu Inan, his brothers Abu al-Fadl and Abu Salim, fled to Granada. Yusuf refused pressure from the Marinid Sultan to hand them over.[58] Like many other Nasrid sultans, Yusuf found that the presence of Marinid pretenders in his court gave him leverage in case the two states came into conflict.[5]

At Yusuf's encouragement, Abu al-Fadl then went to Castile to seek help from Peter. Peter, seeking to incite another civil war in North Africa, provided ships to land the prince in Sus in order to attack Abu Inan.[58][59] The Marinid Sultan was extremely angered by Yusuf's actions but felt unable to take action, knowing that he was supported by Castile.[60] Abu al-Fadl was subsequently captured by Abu Inan and executed in 1354 or 1355.[58][61] Abu Salim eventually became sultan in 1359–1361, well after Yusuf's death.[62]

Architecture

_of_the_Partal_Palace.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Yusuf constructed the Bab al-Sharia (now the Tower of Justice) in the Alhambra in 1348, forming the grand entrance to the complex. He also built what is now the Broken Tower (Torre Quebrada) of the Citadel of the Alhambra. He also carried out work in the Comares Palace, including renovations of its hammam (bathhouse), as well as the construction of the Hall of the Comares, also known as the Chamber of the Ambassadors, the largest Nasrid structure in the complex. He built various new walls and towers to accommodate his enlargement of the Comares, and adorned many of the courts and halls of the Alhambra, as may be seen from the repeated appearance of his name in the inscriptions on the walls.[63] Also in the Alhambra, he built the small prayer hall (oratorio) of the Partal Palace, and what is now the Gate of the Seven Floors.[2] He built or converted two of the towers in the Alhambra's northern ramparts into small palatial residences, which became a novel feature of Nasrid architecture in this period.[64] These two towers are known today as the Peinador de la Reina (which Charles V expanded in the 16th century for new royal apartments) and the Torre de la Cautiva (Tower of the Captive).[65][66]

In 1349, he founded a religious school, the Madrasa Yusufiyya, near the Great Mosque of Granada (now Granada Cathedral), providing higher education comparable to that of the medieval universities in Bologna, Paris and Oxford. Only its prayer room remains today.[2][63] He built al-Funduq al-Jadida ("the new funduq"), today's Corral del Carbón in the city of Granada, the only remaining caravanserai from the Nasrid era.[67] Outside Granada, he enlarged the Alcazaba of Málaga, the ancestral home of his paternal grandfather, Abu Said Faraj, the former governor of Málaga, as well as the city's Gibralfaro precinct.[63]

Yusuf also constructed new defensive structures throughout his realm, including new towers, gates and barbicans, especially after the defeat of Río Salado. He reinforced existing castles and walls, as well as coastal defences. The hajib Ridwan built forty watchtowers (tali'a), stretching the entire length of the Emirate's southern coast.[68] Yusuf reinforced the city walls of Granada, as well as the Bab Ilbira (now the Gate of Elvira) and the Bab al-Ramla (the Gate of the Ears).[63][2]

Administration

Yusuf's administration was supported by numerous ministers, including "a constellation of major cultural figures", according to Fernández-Puertas. Among them was Ridwan, who held the post of hajib (chamberlain), a title created for the first time in the Nasrid rule for him by Muhammad IV and which outranked that of the vizier and other ministers. The hajib had command of the army in the absence of the sultan. He was dismissed and imprisoned after the defeat at Río Salado; he was freed a year later but then refused Yusuf's offer to reappoint him as vizier.[69] The next hajib, Abu al-Hasan ibn al-Mawl, came from a prominent family but proved unskilled in political matters.[70][71] He was dismissed after a few months and fled to North Africa to avoid the intrigues of his rivals.[70] The office of hajib remained vacant until Ridwan regained it under Yusuf's successor Muhammad V (first reign, 1354–1359); following Ridwan's assassination in 1359, the post again disappeared until the appointment of Abu al-Surrur Mufarrij by Yusuf III (r. 1408–1417).[72][69]

The famous poet Ibn al-Jayyab was appointed as vizier in 1341, becoming the highest-ranked minister and the mastermind of Yusuf's cautious policy after Río Salado.[56] He was also the royal secretary, therefore he was titled dhu'l-wizaratayn ("the holder of the two vizierates").[56][73] The Black Death struck the emirate in 1348 and outbreaks were recorded in its three largest cities: Granada, Málaga and Almería. The epidemic killed many scholars and officials, including Ibn al-Jayyab who died in 1349.[2][74] In accordance with his wishes, he was succeeded as both vizier and royal secretary by his protégé, Ibn al-Khatib.[70][71] Ibn al-Khatib had entered the court chancery (diwan al-insha) in 1340, replacing his father who died at Río Salado and serving under Ibn al-Jayyab.[74] After becoming vizier he was also appointed to other posts, such as superintendent of the finances.[56] The "preeminent writer and intellectual of fourteenth-century al-Andalus" according to Catlos,[75] throughout his lifetime Ibn al-Khatib produced works in subjects as diverse as history, poetry, medicine, manners, mysticism and philosophy.[76] With access to official documents and the court archives, he remains one of the main historical sources on the Emirate of Granada.[56][77]

Yusuf received his subjects publicly twice each week, on Monday and Thursday, to listen to their concerns, assisted by his ministers and members of the royal family. According to Shihab al-Din al-'Umari, these hearings included the recitation of a tenth of the Quran and some parts of the hadith. On solemn state occasions, Yusuf presided over court activities from a wooden folding armchair that is currently preserved in the Museum of the Alhambra and bears the Nasrid coat of arms across its back.[78] Between April and May 1347, he made a state visit to his eastern regions, with the main purpose of inspecting the fortifications in this part of his realm. Accompanied by his court, he visited twenty places in twenty-two days, including the port of Almería, where he was well received by the populace.[2] Ibn al-Khatib describes other anecdotes that illustrate Yusuf's popularity, including his reception by a well-respected judge in Purchena, by the people—including common womenfolk—of Guadix in 1354 and by certain Christian merchants in the same year.[79][lower-alpha 4] According to Vidal Castro, gold coins bearing Yusuf's name had particularly beautiful designs, many of which are still found today (one example is provided in the infobox of this article).[2]

In diplomacy, for the first time in Nasrid history he sent an embassy to the Mamluk Sultanate of Cairo. A surviving copy of a letter from the Mamluk Sultan al-Salih Salih indicates that Yusuf had requested military help to fight the Christians; al-Salih prayed for Yusuf's victory but declined to send troops, saying they were needed for conflicts on his own borders.[81] Many of Yusuf's diplomatic exchanges with the rulers of North Africa—especially the Marinid sultans—are preserved in Rayhanat al-Kuttab compiled by Ibn al-Khatib.[82]

In the judiciary, the chief judge (qadi al-jama'a) Abu Abdullah Muhammad al-Ash'ari al-Malaqi, who was appointed by Muhammad IV continued to serve under Yusuf until his death at the battle of Río Salado.[83] He was known for his strong opinions; in one occasion, he wrote a poem to Yusuf warning him of officials who squandered tax revenues, and in another, he reminded the Sultan of his responsibilities to his subjects as a Muslim leader.[84] After the death of al-Malaqi, Yusuf appointed, consecutively, Muhammad ibn Ayyash, Ibn Burtal and Abu al-Qasim Muhammad al-Sabti.[83] The latter resigned in 1347 and Yusuf then appointed Abu al-Barakat ibn al-Hajj al-Balafiqi, who had previously served as a judge in various provinces and was known for his love of literature.[85] Yusuf strengthened the function of the muftis, distinguished jurists who issued legal opinions (fatwas), often to assist judges in interpreting difficult points of Islamic law.[86] The Madrasa Yusufiyya, where Maliki Islamic law was among the subjects taught, was created partly to increase the influence of the muftis.[86][87] Yusuf's emphasis of the rule of law and his appointment of distinguished judges improved his standing among his subjects and among other Muslim monarchies.[79] On the other hand, Yusuf had a mystical inclination that displeased the jurists (fuqaha) in his court, including his appreciation of the famous philosopher al-Ghazali (1058–1111), whose Sufi doctrines were disliked by the mainstream scholars.[2]

Family

According to Ibn al-Khatib, Yusuf began "playing with the idea of taking a concubine" after his accession.[6] He had two concubines, both originally from the Christian lands, named Buthayna and Maryam or Rim.[lower-alpha 1] His union with Buthayna might have taken place in 737 AH (c. 1337 CE), the date of a poem written by Ibn al-Jayyab about the wedding celebration. The wedding took place in a rainy day, and a horse race was held in its honour.[88] In 1339 Buthayna gave birth to Yusuf's first son Muhammad (later Muhammad V), and subsequently to a daughter named Aisha. Maryam/Rim bore him seven children: two sons—Ismail (later Ismail II, r. 1359–1360), who was born nine months after Muhammad, and Qays—as well as five daughters—Fatima, Mu'mina, Khadija, Shams and Zaynab. The eldest daughter married her cousin, the future Muhammad VI (r. 1360–1362). Maryam/Rim's influence was said to be greater than that of Buthayna, and Yusuf favoured his second son Ismail above his other children.[68] Yusuf had another son, Ahmad, whose mother is unknown.[89] He also had a wife, who was the daughter of a Nasrid relative. Apart from their wedding in 738 AH (c. 1338 CE), there is no reference to this wife in the historical sources, leading the historian Bárbara Boloix Gallardo to speculate that she might have died early.[90] Initially, Yusuf designated Ismail as his heir, but later—a few days before his death—he named Muhammad instead because he was considered to have a better judgement. Both Muhammad and Ismail were aged around 15 at Yusuf's death.[91][92]

The education of the children was entrusted to Abu Nu'aym Ridwan,[68] the hajib who was a former Christian and managed to teach the young Ismail some Greek.[93] Yusuf's grandmother Fatima, who had been influential in the Granadan court for multiple generations, died in 1349 aged 90 lunar years, and received an elegy from Ibn al-Khatib.[94] The activity of Yusuf's mother Bahar was also attested: when the North African traveller Ibn Battuta visited Granada in 1350 and sought a royal audience, Yusuf was sick and in his place Bahar provided Ibn Battuta with enough money for his stay,[95] even though it was unknown if Bahar actually met him or if he was received inside the Alhambra.[96] Yusuf's concubine Maryam/Rim played an important role after his death: In 1359, she financed a coup that involved 100 men and deposed her stepson Muhammad V in favour of her son Ismail.[97]

Other than his predecessor Muhammad, Yusuf had another elder half-brother, Faraj, who moved overseas after Yusuf's succession. He later returned to the emirate, and was subsequently imprisoned and killed—probably for political reasons—on Yusuf's order in Almería, 751 AH (1350 or 1351). Yusuf also imprisoned his younger half-brother, Ismail, who was later freed by Muhammad V and then settled in North Africa. Additionally, Yusuf had two half-sisters, Fatima and Maryam, whose marriages he arranged. One of them was married to Abu al-Hasan Ali, a distant member of the Nasrid family.[2]

Death

Yusuf was assassinated whilst praying in Granada's Great Mosque on 19 October 1354 (Eid al-Fitr/1 Shawwal 755 AH). A man stabbed him with a dagger during the last prostration of the Eid prayer ritual. Ibn al-Khatib was present—likely praying a few metres from the Sultan, given that he was then a high court official—and his works include a detailed narration of the events.[98] The attacker broke from the ranks of the congregation and went towards the Sultan. His movement was not noticed or did not alarm anyone because of his condition and rank (see next paragraph), and upon reaching the Sultan, he leapt and stabbed him. The solemn prayer was then interrupted and Yusuf was carried to his royal apartment in the Alhambra, where he died. The assassin was interrogated, but his words were unintelligible. He was soon killed by a mob.[99] His body was burnt (according to Ibn al-Khatib, though this statement might have referred to his supposed burning in hellfire) or "cut into a thousand pieces" (according to Ibn Khaldun).[68][100]

Ibn al-Khatib's account presents the murder as an act of a madman (mamrur) without any motive,[101] and this is also the main account presented by Fernández-Puertas and Harvey, although the latter adds that the lack of reported motive "fill[s] one with suspicion".[68][100] Ibn Khaldun, as well as another Arab near-contemporary historian, Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani, concurred that the attacker was a madman of low rank and intelligence. Ibn Khaldun added that he was a slave in the royal stables whom some suspected to be a bastard son of Muhammad IV with a black woman. This led Vidal Castro to suggest an alternative explanation that it was a politically motivated attack instigated by a third party.[102] Vidal Castro considers it unlikely that the attacker planned a political plot of his own, given his mental condition, or that the instigators aimed to have a demented bastard enthroned, given that Yusuf had his own sons as heirs. Instead, the historian suggests that the objective was simply to kill Yusuf and to end his rule, taking advantage of the attacker's unique condition. As Yusuf's supposed nephew, he would have an easier access to the Sultan, and with his mental condition he could be easily manipulated to conduct a likely suicidal attack without knowing its actual objective. In addition, it allowed the attack to be dismissed simply as a madman's action.[103] Vidal Castro speculates that the real instigators could have been a faction at court whose identity and specific motives for killing Yusuf are unknown, or agents of the Marinid Sultan Abu Inan, whose relations with Yusuf soured towards the end of the latter's reign.[104]

Legacy

Yusuf was succeeded by his eldest son, who became Muhammad V.[63] Yusuf was buried in the royal cemetery (rawda) of the Alhambra, alongside his great-grandfather, Muhammad II, and his father, Ismail I. Centuries later, with the surrender of Granada, the last sultan, Muhammad XII (also known as Boabdil), exhumed the bodies in this cemetery and reburied them in Mondújar, part of his Alpujarras estates.[105] Fernández-Puertas describes the reigns of Yusuf and his successor Muhammad V as the "climax" of the Nasrid period, as seen from the realm's architectural and cultural output, and the flourishing of the study of medicine.[lower-alpha 5][106] Similarly, the historian Brian A. Catlos describes the reigns of these two sultans as the emirate's "era of greatest glory",[94] and Rachel Arié describes the same period as its "apogee".[107] L. P. Harvey describes Yusuf's cultural achievements as "considerable" and "solid", and as marking the beginning of the dynasty's "Golden Age". Furthermore, Yusuf's Granada survived the "onslaught of Alfonso XI's attacks" and at the end reduced its dependency on the Marinids. However, Harvey notes that he was defeated at Río Salado, "the greatest single reverse suffered by the Muslim cause" during the Nasrid period before the fall of Granada, and presided over the strategically significant losses of Algeciras and Alcalá de Benzaide.[108]

Footnotes

- Yusuf's second concubine was named "Maryam" by Fernández-Puertas 1997, p. 13 and Vidal Castro: Yusuf I and "Rim" by Boloix Gallardo 2013, p. 74. Boloix Gallardo argues that "Maryam" is a misreading: in the Arabic script, bi-Rim (بريم, "by Rim") appears very similar to Maryam (مريم)

- The Orders of Alcántara and Santiago—as well as of Calatrava, not mentioned in this article—were Christian military orders created in the twelfth century to fight against Muslims on the Iberian Peninsula. Each was led by a master; they controlled castles in the border area and formed a major component of the Castilian military at this time.[23]

- The Kingdom of Murcia—formerly a Muslim kingdom—was one of the territories that constituted Alfonso's realm, the Crown of Castile.[52]

- The origin of the merchants mentioned by Ibn al-Khatib in this instance is unclear, but foreign trade outposts had been established in Granada's major cities by Catalan merchants, at least since the 1320s.[80]

- Among the prominent scholars of medicine during Yusuf's reign were al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Qaysi, an expert in poison and antidotes who was called "the last great magician-sage of al-Andalus" by Ibn al-Khatib; the doctor of the royal household Muhammad al-Shaquri; as well as Yahya ibn Hudhayl al-Tujibi, the teacher of al-Shaquri and Ibn al-Khatib.[106]

References

- Latham & Fernández-Puertas 1993, p. 1020.

- Vidal Castro: Yusuf I.

- Boloix Gallardo 2013, p. 72.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, p. 7.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, p. 8.

- Boloix Gallardo 2013, p. 73.

- Harvey 1992, pp. 9, 40.

- Harvey 1992, pp. 160, 165.

- O'Callaghan 2013, p. 456.

- Harvey 1992, pp. 26–28.

- Vidal Castro: Muhammad IV.

- Latham & Fernández-Puertas 1993, p. 1023.

- Harvey 1992, p. 188.

- Harvey 1992, pp. 188–189.

- Catlos 2018, pp. 345–346.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, pp. 8–9.

- Harvey 1992, p. 191.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 165.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 165–166.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 166.

- Harvey 1992, p. 190.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 169.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 222.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 169–170.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 171–172.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 171.

- Arié 1973, p. 267.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 174–175.

- Harvey 1992, p. 193.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 175.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 177.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 182.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 183.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 184.

- Harvey 1992, p. 194.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 190.

- Harvey 1992, p. 195.

- Harvey 1992, pp. 197–178.

- Harvey 1992, p. 198.

- Arié 1973, p. 268.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 193.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 197.

- Harvey 1992, pp. 202–203.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 204.

- Harvey 1992, p. 203.

- Harvey 1992, p. 199.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 195.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 198–199.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 205–206.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 206–207.

- Harvey 1992, pp. 203–204.

- O'Callaghan 2013, pp. 428–429.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 213–214.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 214.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 216.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, p. 10.

- O'Callaghan 2014, pp. 13–14.

- O'Callaghan 2014, p. 14.

- Arié 1973, p. 104.

- Arié 1973, pp. 103–104.

- Arié 1973, p. 105.

- Harvey 1992, p. 209.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, p. 14.

- Arnold 2017, p. 278.

- Arnold 2017, pp. 275–278.

- López 2011, pp. 195–196.

- Latham & Fernández-Puertas 1993, p. 1028.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, p. 13.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, p. 9.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, pp. 9–10.

- Arié 1973, p. 206.

- Arié 1973, p. 200.

- Arié 1973, p. 210.

- Arié 1973, p. 439.

- Catlos 2018, p. 350.

- Bosch-Vilá 1971, p. 836.

- Arié 1973, p. 179.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, p. 12.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, p. 11.

- Arié 1973, pp. 318–319.

- Arié 1973, pp. 105, 109.

- Arié 1973, p. 180, also note 3.

- Arié 1973, p. 279.

- Arié 1973, p. 283.

- Arié 1973, pp. 280–281.

- Arié 1973, p. 291.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, pp. 10–101.

- Boloix Gallardo 2013, p. 74.

- Boloix Gallardo 2013, p. 76.

- Boloix Gallardo 2013, pp. 76–77.

- Vidal Castro: Ismail II.

- Arié 1973, p. 197.

- Arié 1973, p. 424.

- Catlos 2018, p. 346.

- Arié 1973, p. 196, also note 4.

- Dunn 2005, pp. 285–286.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, p. 16.

- Vidal Castro 2004, p. 367.

- Vidal Castro 2004, pp. 366–367.

- Harvey 1992, pp. 204–205.

- Vidal Castro 2004, p. 368.

- Vidal Castro 2004, pp. 368–369.

- Vidal Castro 2004, p. 369.

- Vidal Castro 2004, pp. 369–370.

- Arié 1973, p. 198.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, pp. 11–12.

- Arié 1973, p. 101.

- Harvey 1992, pp. 190, 205.

Sources

- Arié, Rachel (1973). L'Espagne musulmane au temps des Nasrides (1232–1492) (in French). Paris: E. de Boccard. OCLC 3207329.

- Arnold, Felix (2017). Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean: A History. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190624552.001.0001. ISBN 978-0190624552.

- Boloix Gallardo, Bárbara (2013). Las sultanas de la Alhambra: las grandes desconocidas del reino nazarí de Granada (siglos XIII–XV) (in Spanish). Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y del Generalife. ISBN 978-8490450451.

- Bosch-Vilá, Jacinto (1971). "Ibn al-K̲h̲aṭīb". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume III: H–Iram (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 835–837. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_3252. OCLC 495469525.

- Catlos, Brian A. (2018). Kingdoms of Faith: A New History of Islamic Spain. London: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1787380035.

- Dunn, Ross E. (2005). The Adventures of Ibn Battuta: A Muslim Traveler of the Fourteenth Century. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520243859.

- Fernández-Puertas, Antonio (April 1997). "The Three Great Sultans of al-Dawla al-Ismā'īliyya al-Naṣriyya Who Built the Fourteenth-Century Alhambra: Ismā'īl I, Yūsuf I, Muḥammad V (713–793/1314–1391)". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Third Series. London: Cambridge University Press on behalf of Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 7 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1017/S1356186300008294. JSTOR 25183293. S2CID 154717811.

- Harvey, L. P. (1992). Islamic Spain, 1250 to 1500. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226319629.

- Latham, J.D. & Fernández-Puertas, A. (1993). "Naṣrids". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume VII: Mif–Naz (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 1020–1029. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0855. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- López, Jesús Bermúdez (2011). The Alhambra and the Generalife: Official Guide. TF Editores. ISBN 978-8492441129.

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (2011). The Gibraltar Crusade: Castile and the Battle for the Strait. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. doi:10.9783/9780812204636. ISBN 978-0812204636.

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (2013). A History of Medieval Spain. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9780801468728. ISBN 978-0801468728.

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (2014). The Last Crusade in the West: Castile and the Conquest of Granada. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. doi:10.9783/9780812209358. ISBN 978-0812209358.

- Vidal Castro, Francisco. "Ismail II". Diccionario Biográfico electrónico (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia.

- Vidal Castro, Francisco. "Muhammad IV". Diccionario Biográfico electrónico (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia.

- Vidal Castro, Francisco. "Yusuf I". Diccionario Biográfico electrónico (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia.

- Vidal Castro, Francisco (2004). "El asesinato político en al-Andalus: la muerte violenta del emir en la dinastía nazarí". In María Isabel Fierro (ed.). De muerte violenta: política, religión y violencia en Al-Andalus (in Spanish). Editorial – CSIC Press. pp. 349–398. ISBN 978-8400082680.

.svg.png.webp)