Zabriskie Point (film)

Zabriskie Point /zəˈbrɪski/ is a 1970 American drama film directed by Michelangelo Antonioni and starring Mark Frechette, Daria Halprin, and Rod Taylor. It was widely noted at the time for its setting in the counterculture of the United States. Some of the film's scenes were shot on location at Zabriskie Point in Death Valley.

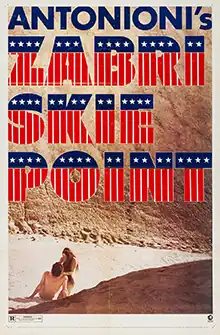

| Zabriskie Point | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michelangelo Antonioni |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Michelangelo Antonioni |

| Produced by | Carlo Ponti |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Alfio Contini |

| Edited by | Franco Arcalli |

| Music by | |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 112 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English[1] |

| Budget | $7 million[2] |

| Box office | $1 million[2][Note 1] |

The film was an overwhelming commercial failure,[4] and was panned by most critics upon release.[5] The film was listed in the 1978 book The Fifty Worst Films of All Time. It has been described as "the worst film ever made by a director of genius".[6] Its critical standing has increased, however, in the decades since.[7] It has to some extent achieved cult status and is noted for its cinematography, use of music, and direction.[8]

Plot

In a room at a university campus, white and black students argue about an impending student strike. Mark leaves the meeting after saying he is "willing to die, but not of boredom" for the cause, which draws criticism from the young white radicals. Following a mass arrest at the campus protest, Mark visits a police station hoping to bail his roommate out of jail. He is told to wait but goes to the lock-up area, asks further about bail for his roommate, is rebuffed, calls out to the arrested students and faculty and is arrested. He gives his name as Karl Marx, which a duty officer types as "Carl Marx". After he is released from jail, Mark and another friend buy firearms from a Los Angeles gun shop, saying they need them for "self-defense" to "protect our women."

In a downtown Los Angeles office building, successful real estate executive Lee Allen reviews a television commercial for Sunny Dunes, a new resort-like real estate development in the desert. Instead of actors or models, the slickly produced commercial features casually dressed, smiling mannequins. In the next scene Allen talks with his associate about the greater Los Angeles area's very rapid growth as the two drive through crowded streets.

Mark goes to a bloody campus confrontation between students and police. Some students are tear-gassed and at least one is shot. As Mark reaches for a gun in his boot, a Los Angeles policeman is seen being fatally shot, although it is unclear by whom.[9] Mark flees the campus and rides a city bus to suburban Hawthorne, California where, after failing to buy a sandwich on credit from a local blue-collar delicatessen, he walks to Hawthorne Municipal Airport, steals a small Cessna 210 aircraft and flies into the desert.

Meanwhile, Daria, "a sweet, pot-smoking post-teenybopper of decent inclinations,” is driving across the desert towards Phoenix in a 1950s-era Buick automobile to meet Lee, her boss, who may or may not also be her lover.[9] Along the way Daria is searching for a man who works with "emotionally disturbed" children from Los Angeles. She finds the young boys near a roadhouse in the Mojave desert, but they tease, taunt, and grab at her, boldly asking for "a piece of ass,” to which she asks in reply, "Are you sure you'd know what to do with it?"

Daria flees in her car. While filling its radiator with water, she is spied from the air by Mark, who buzzes her car and then flies only 15 feet over her as she lies face down in the sand. He throws a T-shirt out of the window of the aircraft for her to pick up. Daria goes from upset to curious and smiling during this sequence.

They later meet at the desert shack of an old man, where Mark asks her for a lift so he can buy gasoline for the aircraft. The two then wander to Zabriskie Point, where they make love. As they begin, other unidentified young naked people are shown playing sexually on the ground, their wild games sending up thick clouds of white dust from the desert floor.[Note 2]

Later, a California highway patrolman suspiciously questions Daria. Hidden behind a portable toilet meant for tourists, Mark takes aim at the policeman, but Daria stands between the two of them to block this, apparently saving the policeman's life before he drives away. Daria asks Mark if he was the one who killed the cop in Los Angeles. He states that he wanted to, but someone else shot the officer first and that he "never got off a shot".

Returning to the stolen aircraft, they paint it with politically charged slogans and psychedelic colors. Daria pleads with Mark to travel with her and leave the aircraft, but Mark is intent on returning and taking the risks that it involves. He flies back to Los Angeles and lands the plane at the airport in Hawthorne. The police (along with some radio and television reporters) are waiting for him, and patrol cars chase the aircraft down the runway. Instead of stopping, Mark tries to turn the taxiing aircraft around across the grass and is shot dead by one of the policemen.

Daria learns about Mark's death on the car radio. She drives to Lee's lavish desert home, "a desert Berchtesgaden"[9] set high on a rock outcropping near Phoenix, Arizona, where she sees three affluent women sunning themselves and chatting by the swimming pool. She grieves for Mark by drenching herself in the house's architectural waterfall. Lee is deeply immersed in a business meeting having to do with the complex and financially risky Sunny Dunes development. Taking a break, he spots Daria in the house and happily greets her. She goes downstairs alone and finds the guest room that has been set aside for her, but after briefly opening the door, she shuts it again.

Seeing a young Native American housekeeper in the hallway, Daria leaves silently. She drives off, but stops to get out of the car and look back at the house, her own imagination seeing it repeatedly blown apart in billows of orange flame and household items.[Note 3]

Cast

- Mark Frechette as Mark

- Daria Halprin as Daria

- Rod Taylor as Lee Allen

- Paul Fix as Roadhouse owner

- G.D. Spradlin as Lee's associate

- Bill Garaway as Morty

- Kathleen Cleaver as Kathleen

- The Open Theatre of Joe Chaikin as Lovemakers in Death Valley

- Austin Willis as board member

Cast notes

- Harrison Ford has an uncredited role[1] as one of the arrested student demonstrators being held inside a Los Angeles police station.

- Frechette, who had frequently been arrested, was first discovered at a bus stop during a verbal confrontation with another man leaning out of the third floor of an apartment building. Antonioni's casting director, Sally Dennison, witnessed the fight and recommended him to the director, noting, "He's twenty, and he hates."[7]

- Daria Halprin and Mark Frechette fell in love and moved together to Mel Lyman's experimental Fort Hill Community. She later was married to Dennis Hopper for four years.[7]

- Along with three other members of the Fort Hill Community, Mark Frechette committed a bank robbery in 1973, using a gun with no bullets. He died in prison, supposedly as the result of a weight-lifting accident.[7]

Production

Development

While in the United States for the 1966 premiere of his film Blowup, which had been a surprising box-office hit, Antonioni saw a short newspaper article about a young man who had stolen an aircraft and was killed when he tried to return it in Phoenix, Arizona. Antonioni took this as a thread, with which he could tie together the plot of his next film. After writing many drafts, he hired playwright Sam Shepard to write the script. Shepard, Antonioni, Italian filmmaker Franco Rossetti, Antonioni's frequent collaborator screenwriter Tonino Guerra and Clare Peploe (later to become the wife of Bernardo Bertolucci), worked on the screenplay.

Casting

The lead roles went to two non-professional actors, Mark Frechette and Daria Halprin. Halprin was cast based on her appearance in the documentary Revolution, and Frechette was offered the role when a casting director overheard him having a heated argument in a bus station. Neither actor performed a screen test.[11]

Most of the supporting roles were played by a professional cast, including, notably, Rod Taylor,[12] along with G. D. Spradlin, in one of his early feature film roles, following many appearances on U.S. national television. Paul Fix, a friend and acting coach of John Wayne who had appeared in many of Wayne's films, played the owner of a roadhouse in the Mojave desert. Kathleen Cleaver, a member of the Black Panthers and wife of Eldridge Cleaver, appeared in the documentary-like student meeting scene at the opening of the film.

Filming

Shooting began in July 1968 in Los Angeles, much of it on location in the wider southern downtown area. Exteriors of the art deco Richfield Tower were shown in a few scenes shot shortly before its demolition in November of that year. Various college campus scenes, excluding the scene of the student meeting, were filmed on location at Contra Costa Community College in San Pablo, California. The production then moved to location shooting at Carefree, Arizona, near Phoenix and from there to Death Valley.[13] The production rented a mansion in Carefree and built a replica of it on the lot of Southwestern Studio in Carefree for the special effect of blowing it up. Location shooting also took place in the Mojave Desert.[14]

Early film industry publicity reports said Antonioni would gather 10,000 extras in the desert for the filming of the lovemaking scene, but this never happened. The scene was filmed with dust-covered and highly choreographed actors from The Open Theatre. The United States Department of Justice investigated whether this violated the Mann Act, which forbade the taking of women across state lines for sexual purposes; however, no sex was filmed and no state lines were crossed, given that Death Valley is in California.[10][13] State officials in Sacramento were also ready to charge Antonioni with "immoral conduct, prostitution or debauchery" if he staged an actual orgy.[7] FBI officials investigated the film because of Antonioni's political views, and officials in Oakland, California, accused the director of staging a real riot for a scene early in the film.[7]

During filming, Antonioni was quoted as criticizing the U.S. film industry for financially wasteful production practices, which he found "almost immoral" compared to the more thrifty approach of Italian studios.[13]

Music

Soundtrack

The soundtrack to Zabriskie Point includes music from Pink Floyd, The Youngbloods, Kaleidoscope, Jerry Garcia, Patti Page, Grateful Dead, the Rolling Stones, and John Fahey. Roy Orbison wrote and sang the theme song, over the credits, called "So Young (Love Theme from Zabriskie Point)".

Unused music

Richard Wright of Pink Floyd wrote a song called "The Violent Sequence" for inclusion in the film.[15] Antonioni rejected the song because it was too subdued and instead synchronized a re-recording of the band's "Careful with That Axe, Eugene", retitled "Come in Number 51, Your Time Is Up", with the film's violent ending scene. Roger Waters states in Classic Albums – Pink Floyd – Making The Dark Side of the Moon that while he loved the song, Antonioni said it was "too sad" and that it reminded him of church. Eventually it was reworked into a new song known as "Us and Them", which was released on their album The Dark Side of the Moon in 1973. "The Violent Sequence" remained unreleased until it was included on a 2011 boxed set of Dark Side of the Moon, where it was named "Us and them (Richard Wright Demo)".[15]

Other discarded pieces recorded for the film by Pink Floyd were released on a bonus disc with the 1997 CD re-release of the soundtrack album, along with pieces by Jerry Garcia.[15]

John Fahey was flown to Rome to record some music for the film, but it was not used.[16] The accounts of Fahey and others differ.[17] However, a portion of his Dance of Death was used in the film.[4] Antonioni visited The Doors while they were recording their album L.A. Woman and thought about putting them in the soundtrack. The Doors recorded the song "L'America" for Zabriskie Point, but it was not used.[18]

Mark Frechette was living at Mel Lyman's intentional community at Fort Hill, Boston, at the time he made this film. He and Lyman hoped that the soundtrack would include some of the Americana type music Lyman had recorded with Jim Kweskin and the Jug Band. Frechette left copies of Lyman's newspaper Avatar around the studio and took time to play tapes of the band for the director and explain Lyman's work. When Antonioni seemed oblivious to the perceived importance of Lyman's music, Frechette quit the film, but returned six days later.[19]

Release

Following prolonged publicity and controversy in North America throughout its production, Zabriskie Point had its premiere at Walter Reade's Coronet Theatre in New York City on February 5, 1970, almost four years after Antonioni began pre-production and over a year and a half after shooting began, before being generally released on February 9, 1970.[20]

Certification

Despite the explicit language and sexual content, the film received an R rating rather than an X, in a shift in the MPAA's policy.[21]

Reception

The film was panned by most critics and other published commentators of all political stripes, as were the performances of Frechette and Halprin. The New York Times reviewer Vincent Canby called Zabriskie Point "a noble artistic impulse short-circuited in a foreign land."[9] Roger Ebert echoed Canby, writing: "The director who made Monica Vitti seem so incredibly alone is incapable, in Zabriskie Point, of making his young characters seem even slightly together. Their voices are empty; they have no resonance as human beings. They don't play to each other, but to vague narcissistic conceptions of themselves. They wouldn't even meet were it not for a preposterous Hollywood coincidence."[22]

The counterculture audience MGM hoped to draw largely ignored the film during its brief theatrical run and taken altogether the outcome was a notorious box-office bomb. Production expenses were at least $7 million and only $900,000 was made in the domestic release. The film was listed in the 1978 book The Fifty Worst Films of All Time. It has been described as "the worst film ever made by a director of genius" but it "is still absolutely watchable because of the magic of Antonioni's eye".[23] Over 20 years after the film's release, Rolling Stone editor David Fricke wrote that "Zabriskie Point was one of the most extraordinary disasters in modern cinematic history."[24] It was the only film Antonioni directed in the United States, where in 1994 he was given the Honorary Academy Award "in recognition of his place as one of the cinema's master visual stylists."

With early 21st-century screenings of pristine wide-screen prints and a later DVD release, Zabriskie Point at last garnered some critical praise, mostly for the stark beauty of its cinematography and innovative use of music in the soundtrack, but opinions about the film were still mixed.[8] Director Stéphane Sednaoui referenced the film in his video for "Today" by The Smashing Pumpkins, where an ice-cream salesman steals his employer's ice-cream van, escapes to the desert, and colourfully paints the van while couples kiss in the desert.[25] In 1998, Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader included the film in his unranked list of the best American films not included on the AFI Top 100.[26]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 66% approval rating based on 32 reviews from film critics, with an average rating of 6.5/10.[27]

References

Informational notes

- 513,312 admissions (France)[3]

- The music is performed by The Open Theater.[10]

- The scene has been described as a metaphor for her sadness and anger.[9]

Citations

- Zabriskie Point at the American Film Institute Catalog

- "Box office: business for Zabriskie Point (1970)." Archived April 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine IMDb. Retrieved: October 18, 2011.

- "1970 French box office figures." Box Office Story. Retrieved: November 21, 2016.

- Smith, Matt. "Zabriskie Point.' Archived July 14, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Brattle Theatre Film Notes {Brattle Film Foundation}. Retrieved: September 19, 2012.

- Chatman and Duncan 2004, p. 118. Archived November 12, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- Craven, Peter. "Uneasy moments from master of angst." The Age, A2, May 17, 2008, p. 20.

- Thompson, Nathaniel "Zabriskie Point (1970)" (article) Archived September 6, 2018, at the Wayback Machine TCM.com

- Allwood, Emma Hope. "Three things you don't know about Zabriskie Point." Archived July 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Dazed, July 2015. Retrieved: November 21, 2016.

- Canby, Vincent. "Screen: Antonioni's 'Zabriskie Point'". The New York Times, February 10, 1970. Retrieved: February 2, 2010.

- Out of the past." Archived July 14, 2020, at the Wayback Machine moviecrazed.com. Retrieved: February 2, 2010.

- Lewis 2019, pp. 68–69.

- Vagg 2010, p. 144.

- "Making Zabriskie Point." Archived May 30, 2023, at the Wayback Machine chainedandperfumed.wordpress.com, November 17, 2009. Retrieved: January 29, 2010.

- "Notes" Archived September 6, 2018, at the Wayback Machine TCM.com

- Mabbett 2010

- Fahey 2000 pp. 184–185

- Lowenthal, Steve and Fricke, David (2014) Dance of Death: The Life of John Fahey, American Guitarist. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. pp. 94–97 ISBN 9781613745229

- Weiss, Jeff (January 19, 2012). "L.A. Woman: Track List". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on June 8, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- Felton, David (December 1971 & January 1971)) "The Lyman Family's Holy Siege of America" (two-part article) Archived September 8, 2018, at the Wayback Machine originally from Rolling Stone #98, pp. 40–60 and #99, pp. 40–60. Republished in Steve Trussel's Mel Lyman archive website. Retrieved: November 21, 2016.

- "Golden People (With Colored Tickets) Climax 'Zabriskie's' Gumshoe Ballyhoo". Variety. February 11, 1970. p. 6.

- "'Zabriskie's' R Poses Questions". Variety. February 11, 1970. p. 6.

- Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1970). "Review: 'Zabriskie Point'". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on December 16, 2018. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- Craven, Peter. "Uneasy moments from master of angst." The Age, A2, May 17, 2008, p. 20.

- Fricke, David. "Zabriskie Point." Archived 2006-08-11 at the Wayback Machine phinnweb.org. Retrieved: February 3, 2010.

- "Commentary for "Today" music video." The Smashing Pumpkins 1991–2000: Greatest Hits Video Collection (Virgin Records), 2001.

- Rosenbaum, Jonathan (June 25, 1998). "List-o-Mania: Or, How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love American Movies". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020.

- "Zabriskie Point". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. February 9, 1970. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2023.

Bibliography

- Chatman, Seymour and Paul Duncan (2004) Michelangelo Antonioni: The Complete Films. Koln, Germany: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-3089-5.

- Fahey, John (2000) How Bluegrass Music Destroyed My Life. Chicago: Drag City. ISBN 978-0-9656183-2-8.

- Lewis, Jon (2019). "Antonioni's America: Blow-Up, Zabriskie Point, and the Making of a New Hollywood". In Kirshner, Jonathan; Lewis, Jon (eds.). When The Movies Mattered: The New Hollywood Revisited. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Mabbett, Andy (2010) Pink Floyd: The Music and the Mystery. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84938-370-7.

- Medved, H. and R. Dreyfus (1978) The Fifty Worst Films of All Time (And How They Got That Way). New York: Popular Library. ISBN 978-0-445-04139-4.

- Vagg, Stephen (2010) Rod Taylor: An Aussie in Hollywood. Albany, Georgia: Bear Manor Media. ISBN 978-1-59393-511-5.

External links

- Zabriskie Point at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Zabriskie Point at IMDb

- Zabriskie Point at the TCM Movie Database

- Zabriskie Point at Rotten Tomatoes

- Zabriskie Point @ pHinnWeb

- Return to Zabriskie Point: The Mark Frechette and Daria Halprin Story at Confessions of a Pop Culture Addict

- Review of Zabriskie Point at Girls, Guns and Ghouls