Zambezi

The Zambezi (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers 1,390,000 km2 (540,000 sq mi),[1][2] slightly less than half of the Nile's. The 2,574-kilometre-long (1,599 mi) river rises in Zambia and flows through eastern Angola, along the north-eastern border of Namibia and the northern border of Botswana, then along the border between Zambia and Zimbabwe to Mozambique, where it crosses the country to empty into the Indian Ocean.[7][8]

| Zambezi River Zambesi, Zambeze | |

|---|---|

The Zambezi River at the junction of Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Botswana | |

| |

| Nickname(s) | Besi |

| Location | |

| Countries | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Main stem source. Zambezi Source National Forest |

| • location | Ikelenge District, North-Western Province, Zambia |

| • coordinates | 11°22′11″S 24°18′30″E |

| • elevation | 1,500 m (4,900 ft) |

| 2nd source | Most distant source of the Zambezi-Lungwebungu system |

| • location | Moxico Municipality, Moxico Province, Angola |

| • coordinates | 12°40′34″S 18°24′47″E |

| • elevation | 1,440 m (4,720 ft) |

| Mouth | Indian Ocean |

• location | Zambezia Province and Sofala Province, Mozambique |

• coordinates | 18°34′14″S 36°28′13″E |

| Length | 2,574 km (1,599 mi) |

| Basin size | 1,390,000 km2 (540,000 sq mi)[1][2] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Zambezi Delta, Mozambique, Indian Ocean |

| • average | 3,424 m3/s (120,900 cu ft/s)[1][2]

4,134 m3/s (146,000 cu ft/s)[3] 3,896.189 m3/s (137,592.6 cu ft/s)[4] |

| • minimum | 920 m3/s (32,000 cu ft/s) |

| • maximum | 18,600 m3/s (660,000 cu ft/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Cahora Bassa Dam (Basin size: 1,068,237 km2 (412,449 sq mi) |

| • average | 2,652.541 m3/s (93,673.6 cu ft/s)[4] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Kariba Dam (Basin size: 679,343.6 km2 (262,296.0 sq mi) |

| • average | 1,315.381 m3/s (46,452.2 cu ft/s)[5] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Victoria Falls |

| • average | 1,065.982 m3/s (37,644.8 cu ft/s)[5] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Lukulu |

| • average | 1,287.923 m3/s (45,482.6 cu ft/s)[6] |

| Basin features | |

| River system | Zambezi Basin |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Luena, Lungwebungu, Luanginga, Chobe, Gwayi, Sanyati, Panhane, Luenha |

| • right | Kabompo, Kafue, Luangwa, Capoche, Shire |

The Zambezi's most noted feature is Victoria Falls. Its other falls include the Chavuma Falls[9] at the border between Zambia and Angola, and Ngonye Falls near Sioma in western Zambia.[10]

The two main sources of hydroelectric power on the river are the Kariba Dam, which provides power to Zambia and Zimbabwe, and the Cahora Bassa Dam in Mozambique, which provides power to Mozambique and South Africa. Additionally, two smaller power stations are along the Zambezi River in Zambia, one at Victoria Falls and the other in Zengamina, near Kalene Hill in the Ikelenge District.[11][12]

Course

Origins

The river rises in a black, marshy dambo in dense, undulating miombo woodland 50 km (31 mi) north of Mwinilunga and 20 km (12 mi) south of Ikelenge in the Ikelenge District of North-Western Province, Zambia, at about 1,524 metres (5,000 ft) above sea level.[13] The area around the source is a national monument, forest reserve, and important bird area.[14]

Eastward of the source, the watershed between the Congo and Zambezi Basins is a well-marked belt of high ground, running nearly east–west and falling abruptly to the north and south. This distinctly cuts off the basin of the Lualaba (the main branch of the upper Congo) from the Zambezi. In the neighborhood of the source, the watershed is not as clearly defined, but the two river systems do not connect.[15]

The region drained by the Zambezi is a vast, broken-edged plateau 900–1,200 m high, composed in the remote interior of metamorphic beds and fringed with the igneous rocks of the Victoria Falls. At Chupanga, on the lower Zambezi, thin strata of grey and yellow sandstones, with an occasional band of limestone, crop out on the bed of the river in the dry season, and these persist beyond Tete, where they are associated with extensive seams of coal. Coal is also found in the district just below Victoria Falls. Gold-bearing rocks occur in several places.[16]

Upper Zambezi

The river flows to the southwest into Angola for about 240 km (150 mi), then is joined by sizeable tributaries such as the Luena and the Chifumage flowing from highlands to the north-west.[15] It turns south and develops a floodplain, with extreme width variation between the dry and rainy seasons. It enters dense evergreen Cryptosepalum dry forest, though on its western side, Western Zambezian grasslands also occur. Where it re-enters Zambia, it is nearly 400 m (1,300 ft) wide in the rainy season and flows rapidly, with rapids ending in the Chavuma Falls, where the river flows through a rocky fissure. The river drops about 400 m (1,300 ft) in elevation from its source at 1,500 m (4,900 ft) to the Chavuma Falls at 1,100 m (3,600 ft), in a distance of about 400 km (250 mi). From this point to the Victoria Falls, the level of the basin is very uniform, dropping only by another 180 m (590 ft) in a distance around 800 km (500 mi).[17]

The first of its large tributaries to enter the Zambezi is the Kabompo River in the North-Western Province of Zambia. The savanna through which the river flows gives way to a wide floodplain, studded with Borassus fan palms. A little farther south is the confluence with the Lungwebungu River. This is the beginning of the Barotse Floodplain, the most notable feature of the upper Zambezi, but this northern part does not flood so much and includes islands of higher land in the middle.[18]

About 30 km below the confluence of the Lungwebungu, the country becomes very flat, and the typical Barotse Floodplain landscape unfolds, with the flood reaching a width of 25 km in the rainy season. For more than 200 km downstream, the annual flood cycle dominates the natural environment and human life, society, and culture. About 80 km further down, the Luanginga, which with its tributaries drains a large area to the west, joins the Zambezi. A short distance higher up on the east, the main stream is joined in the rainy season by overflow of the Luampa/Luena system.[15]

A short distance downstream of the confluence with the Luanginga is Lealui, one of the capitals of the Lozi people, who populate the Zambian region of Barotseland in the Western Province. The chief of the Lozi maintains one of his two compounds at Lealui; the other is at Limulunga, which is on high ground and serves as the capital during the rainy season. The annual move from Lealui to Limulunga is a major event, celebrated as one of Zambia's best-known festivals, the Kuomboka.

After Lealui, the river turns south-southeast. From the east, it continues to receive numerous small streams, but on the west, it is without major tributaries for 240 km. Before this, the Ngonye Falls and subsequent rapids interrupt navigation. South of Ngonye Falls, the river briefly borders Namibia's Caprivi Strip.[15] Below the junction of the Cuando River and the Zambezi, the river bends almost due east. Here, the river is broad and shallow and flows slowly, but as it flows eastward towards the border of the great central plateau of Africa, it reaches a chasm into which the Victoria Falls plunge.

Middle Zambezi

The Victoria Falls are considered the boundary between the upper and middle Zambezi. Below them, the river continues to flow due east for about 200 km (120 mi), cutting through perpendicular walls of basalt 20 to 60 m (66 to 197 ft) apart in hills 200 to 250 m (660 to 820 ft) high. The river flows swiftly through the Batoka Gorge, the current being continually interrupted by reefs. It has been described[19] as one of the world's most spectacular whitewater trips, a tremendous challenge for kayakers and rafters alike. Beyond the gorge are a succession of rapids that end 240 km (150 mi) below Victoria Falls. Over this distance, the river drops 250 m (820 ft).

At this point, the river enters Lake Kariba, created in 1959 following the completion of the Kariba Dam. The lake is one of the largest man-made lakes in the world, and the hydroelectric power-generating facilities at the dam provide electricity to much of Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The Luangwa and Kafue rivers are the two largest left-hand tributaries of the Zambezi. The Kafue joins the main river in a quiet, deep stream about 180 m (590 ft) wide. From this point, the northward bend of the Zambezi is checked, and the stream continues due east. At the confluence of the Luangwa (15°37' S), it enters Mozambique.[20]

The middle Zambezi ends where the river enters Lake Cahora Bassa, formerly the site of dangerous rapids known as Kebrabassa; the lake was created in 1974 by the construction of the Cahora Bassa Dam.[21]

Lower Zambezi

The lower Zambezi's 650 km from Cahora Bassa to the Indian Ocean is navigable, although the river is shallow in many places during the dry season. This shallowness arises as the river enters a broad valley and spreads out over a large area. Only at one point, the Lupata Gorge, 320 km from its mouth, is the river confined between high hills. Here, it is scarcely 200 m wide. Elsewhere it is from 5 to 8 km wide, flowing gently in many streams. The river bed is sandy, and the banks are low and reed-fringed. At places, however, and especially in the rainy season, the streams unite into one broad, fast-flowing river.

About 160 km from the sea, the Zambezi receives the drainage of Lake Malawi through the Shire River. On approaching the Indian Ocean, the river splits up into a delta.[15] Each of the primary distributaries, Kongone, Luabo, and Timbwe, is obstructed by a sand bar. A more northerly branch, called the Chinde mouth, has a minimum depth at low water of 2 m at the entrance and 4 m further in, and is the branch used for navigation. 100 km further north is a river called the Quelimane, after the town at its mouth. This stream, which is silting up, receives the overflow of the Zambezi in the rainy season.[22]

Discharge

Average, minimum and maximum discharge of the Zambezi River at Marromeu (Lower Zambezi). Period from 1998 to 2022.[23]

| Year | Discharge (m3/s) | Year | Discharge (m3/s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | ||

| 1998 | 1,141 | 3,335 | 11,183 | 2011 | 17 | 2,619 | 6,117 |

| 1999 | 600 | 4,259 | 11,084 | 2012 | 1,383 | 3,522 | 7,553 |

| 2000 | 338 | 3,041 | 6,696 | 2013 | 1,243 | 3,877 | 8,622 |

| 2001 | 112 | 9,151 | 39,802 | 2014 | 2,394 | 4,161 | 8,946 |

| 2002 | 631 | 2,536 | 4,910 | 2015 | 3,307 | 6,095 | 15,826 |

| 2003 | 329 | 2,536 | 8,952 | 2016 | 1,754 | 4,418 | 9,124 |

| 2004 | 79 | 2,013 | 4,824 | 2017 | 2,133 | 4,686 | 9,215 |

| 2005 | 888 | 3,030 | 7,973 | 2018 | 2,177 | 4,988 | 8,802 |

| 2006 | 1,549 | 3,651 | 7,575 | 2019 | 2,867 | 5,942 | 12,091 |

| 2007 | 2,208 | 4,636 | 14,141 | 2020 | 3,001 | 5,131 | 10,031 |

| 2008 | 2,881 | 6,949 | 31,975 | 2021 | 2,331 | 5,977 | 10,196 |

| 2009 | 154 | 2,648 | 5,930 | 2022 | 868 | 4,953 | 14,361 |

| 2010 | 58 | 2,284 | 6,342 | 17 | 4,217 | 39,802 | |

Delta

The delta of the Zambezi is today about half as broad as it was before the construction of the Kariba and Cahora Bassa dams controlled the seasonal variations in the flow rate of the river. Before the dams were built, seasonal flooding of the Zambezi had quite a different impact on the ecosystems of the delta from today, as it brought nutrient-rich fresh water down to the Indian Ocean coastal wetlands. The lower Zambezi experienced a small flood surge early in the dry season as rain in the Gwembe catchment and north-eastern Zimbabwe rushed through while rain in the upper Zambezi, Kafue, and Lake Malawi basins, and Luangwa to a lesser extent, is held back by swamps and floodplains.

The discharges of these systems contribute to a much larger flood in March or April, with a mean monthly maximum for April of 6,700 m3 (240,000 cu ft) per second at the delta. The record flood was more than three times as big, 22,500 m3 (790,000 cu ft) per second being recorded in 1958. By contrast, the discharge at the end of the dry season averaged just 500 m3 (18,000 cu ft) per second.[1]

In the 1960s and 1970s, the building of dams changed that pattern completely. Downstream, the mean monthly minimum–maximum was 500 to 6,000 m3 (18,000 to 212,000 cu ft) per second; now it is 1,000 to 3,900 m3 (35,000 to 138,000 cu ft) per second. Medium-level floods especially, of the kind to which the ecology of the lower Zambezi was adapted, happen less often and have a shorter duration. As with the Itezhi-Tezhi Dam's deleterious effects on the Kafue Flats, this has these effects:

- Fish, bird, and other wildlife feeding and breeding patterns were disrupted.

- Less grassland remains after flooding for grazing wildlife and cattle.

- Traditional farming and fishing patterns were disrupted.[24]

Ecology of the delta

The Zambezi Delta has extensive seasonally and permanently flooded grasslands, savannas, and swamp forests. Together with the floodplains of the Buzi, Pungwe, and Save Rivers, the Zambezi's floodplains make up the World Wildlife Fund's Zambezian coastal flooded savanna ecoregion in Mozambique. The flooded savannas lie close to the Indian Ocean coast. Mangroves fringe the delta's shoreline.

Although the dams have stemmed some of the annual flooding of the lower Zambezi and caused the area of floodplain to be greatly reduced, they have not removed flooding completely. They cannot control extreme floods, and they have only made medium-level floods less frequent. When heavy rain in the lower Zambezi combines with significant runoff upstream, massive floods still happen, and the wetlands are still an important habitat. The shrinking of the wetlands, though, resulted in uncontrolled hunting of animals such as buffalo and waterbuck during the Mozambican Civil War.

Although the region has had a reduction in the populations of the large mammals, it is still home to some, including the reedbuck and migrating eland. Carnivores found here include lion (Panthera leo), leopard (Panthera pardus), cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta), and side-striped jackal (Canis adustus). The floodplains are a haven for migratory waterbirds, including pintails, garganey, African openbill (Anastomus lamelligerus), saddle-billed stork (Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis), wattled crane (Bugeranus carunculatus), and great white pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus).[26]

Reptiles include Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus), Nile monitor lizard (Varanus niloticus), African rock python (Python sebae), the endemic Pungwe worm snake (Leptotyphlops pungwensis), and three other snakes that are nearly endemic - floodplain water snake (Lycodonomorphus whytei obscuriventris), dwarf wolf snake (Lycophidion nanus), and swamp viper (Proatheris).[26]

Several butterfly species are endemic.

The Zambezi's delta

The Zambezi's delta The river and its floodplain near Mongu in Zambia

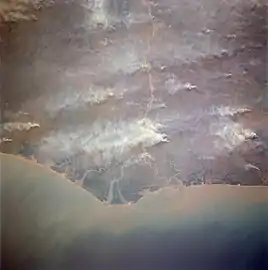

The river and its floodplain near Mongu in Zambia.jpg.webp) Water is black in this false-colour image of the Zambezi flood plain.

Water is black in this false-colour image of the Zambezi flood plain..jpg.webp) This detailed true-colour image shows the stark eastern edge of the Zambezi floodplain.

This detailed true-colour image shows the stark eastern edge of the Zambezi floodplain.

Climate

The north of the Zambezi basin has mean annual rainfall of 1100 to 1400 mm, which declines towards the south, reaching about half that figure in the south-west. The rain falls in a 4-to-6-month summer rainy season when the intertropical convergence zone moves over the basin from the north between October and March. Evaporation rates are high (1600 mm-2300 mm), and much water is lost this way in swamps and floodplains, especially in the south-west of the basin.[27]

Wildlife

The river supports large populations of many animals. Hippopotamuses are abundant along most of the calm stretches of the river, as well as Nile crocodiles. Monitor lizards are found in many places. Birds are abundant, with species including heron, pelican, egret, lesser flamingo, and African fish eagle present in large numbers. Riverine woodland also supports many large animals, such as buffalo, zebras, giraffes, and elephants.

The Zambezi also supports several hundred species of fish, some of which are endemic to the river. Important species include cichlids, which are fished heavily for food, as well as catfish, tigerfish, yellowfish, and other large species. The bull shark is sometimes known as the Zambezi shark after the river, not to be mistaken with Glyphis freshwater shark genus that inhabit the river, as well.

Tributaries

Upper Zambezi: 507,200 km2, discharges 1044 m3/s at Victoria Falls, comprising:

- Northern Highlands catchment, 222,570 km2, 850 m3/s at Lukulu:

- Chifumage River: Angolan central plateau

- Luena River: Angolan central plateau

- Kabompo River: 72,200 km2, NW highlands of Zambia

- Lungwebungu River: 47,400 km2, Angolan central plateau

- Central Plains catchment, 284,630 km2, 196 m3/s (Victoria Falls–Lukulu):

- Luanginga River: 34,600 km2, Angolan central plateau

- Luampa River/Luena River, Zambia: 20,500 km2, eastern side of Zambezi

- Cuando /Linyanti/Chobe River: 133,200 km2, Angolan S plateau & Caprivi

Middle Zambezi cumulatively 1,050,000 km2, 2442 m3/s, measured at Cahora Bassa Gorge

- (Middle section by itself: 542,800 km2, discharges 1398 m3/s (C. Bassa–Victoria Falls)

- Gwembe Catchment, 156,600 km2, 232 m3/s (Kariba Gorge–Vic Falls):

- Gwayi River: 54,610 km2, NW Zimbabwe

- Sengwa River: 25,000 km2, North-central Zimbabwe

- Sanyati River: 43,500 km2, North-central Zimbabwe

- Kariba Gorge to C. Bassa catchment, 386200 km2, 1166 m3/s (C. Bassa–Kariba Gorge):

- Kafue River: 154,200 km2, 285 m3/s, West-central Zambia & Copperbelt

- Luangwa River: 151,400 km2, 547 m3/s, Luangwa Rift Valley & plateau NW of it

- Panhane River: 23,897 km2, North-central Zimbabwe plateau

Lower Zambezi cumulatively, 1,378,000 km2, 3424 m3/s, measured at Marromeu

- (Lower section by itself: 328,000 km2, 982 m3/s (Marromeu–C. Bassa))

- Luia River: 28,000 km2, Moravia-Angonia plateau, N of Zambezi

- Luenha River/Mazoe River: 54,144 km2, 152 m3/s, Manica plateau, NE Zimbabwe

- Shire River , 154,000 km2, 539 m3/s, Lake Malawi basin

- Zambezi Delta, 12,000 km2

Total Zambezi river basin: 1,390,000 km2, 3424 m3/s discharged into delta

Source: Beilfuss & Dos Santos (2001)[1] The Okavango Basin is not included in the figures because it only occasionally overflows to any extent into the Zambezi.

Because of the rainfall distribution, northern tributaries contribute much more water than southern ones; for example: The Northern Highlands catchment of the upper Zambezi contributes 25%, Kafue 8%, Luangwa and Shire Rivers 16% each, total 65% of Zambezi discharge. The large Cuando basin in the south-west, though, contributes only about 2 m3/s because most is lost through evaporation in its swamp systems. The 1940s and 1950s were particularly wet decades in the basin. Since 1975, it has been drier, the average discharge being only 70% of that for the years 1930 to 1958.[1]

Geological history

Up to the Late Pliocene or Pleistocene (more than two million years ago), the upper Zambezi flowed south through what is now the Makgadikgadi Pan to the Limpopo River.[28] The change of the river course is the result of epeirogenic movements that lifted up the surface at the present-day water divide between both rivers.[29]

Meanwhile, 1,000 km (620 mi) east, a western tributary of the Shire River in the East African Rift's southern extension through Malawi eroded a deep valley on its western escarpment. At a slow rate, the middle Zambezi started cutting back the bed of its river towards the west, aided by grabens (rift valleys) forming along its course in an east–west axis. As it did so, it captured several south-flowing rivers such as the Luangwa and Kafue.

Eventually, the large lake trapped at Makgadikgadi (or a tributary of it) was captured by the middle Zambezi cutting back towards it, and emptied eastwards. The upper Zambezi was captured, as well. The middle Zambezi was about 300 m (980 ft) lower than the upper Zambezi, and a high waterfall formed at the edge of the basalt plateau across which the upper river flows. This was the first Victoria Falls, somewhere down the Batoka Gorge near where Lake Kariba is now.[30]

History

Etymology

The first European to come across the Zambezi River was Vasco da Gama in January 1498, who anchored at what he called Rio dos Bons Sinais (River of Good Omens), now the Quelimane or Quá-Qua, a small river on the northern end of the delta, which at that time was connected by navigable channels to the Zambezi River proper (the connection silted up by the 1830s). In a few of the oldest maps, the entire river is denoted as such. By the 16th century, a new name emerged, the Cuama River (sometimes "Quama" or "Zuama"). Cuama was the local name given by the dwellers of the Swahili coast for an outpost located on one of the southerly islands of the delta (near the Luabo channel). Most old nautical maps denote the Luabo entry as Cuama, the entire delta as the "rivers of Cuama", and the Zambezi proper as the "Cuama River".

In 1552, Portuguese chronicler João de Barros noted that the same Cuama River was called Zembere by the inland people of Monomatapa.[31] The Portuguese Dominican friar João dos Santos, visiting Monomatapa in 1597 reported it as Zambeze (Bantu languages frequently shifts between z and r) and inquired into the origins of the name; he was told it was named after a people.

"The River Cuama is by them called Zambeze; the head whereof is so farre within Land that none of them know it, but by tradition of their Progenitors say it comes from a Lake in the midst of the continent which yeelds also other great Rivers, divers ways visiting the Sea. They call it Zambeze, of a Nation of Cafres dwelling neere that Lake which are so called." —J. Santos Ethiopia Oriental, 1609[32]

Thus, the term "Zambezi" is after a people who live by a great lake to the north. The most likely candidates are the "M'biza", or Bisa people (in older texts given as Muisa, Movisa, Abisa, Ambios, and other variations), a Bantu people who live in what is now central-eastern Zambia, between the Zambezi River and Lake Bangweolo (at the time, before the Lunda invasion, the Bisa would have likely stretched further north, possibly to Lake Tanganyika). The Bisa had a reputation as great cloth traders throughout the region.[33]

In a curious note, Goese-born Portuguese trader Manuel Caetano Pereira, who traveled to the Bisa homelands in 1796, was surprised to be shown a second, separate river referred to as the "Zambezi".[34] This "other Zambezi" that puzzled Pereira is most likely what modern sources spell the Chambeshi River in northern Zambia.

The Monomatapa notion (reported by Santos) that the Zambezi was sourced from a great internal lake might be a reference to one of the African Great Lakes. One of the names reported by early explorers for Lake Malawi was "Lake Zambre" (probably a corruption of "Zambezi"), possibly because Lake Malawi is connected to the lower Zambezi via the Shire River. The Monomatapa story resonated with the old European notion, drawn from classical antiquity, that all the great African rivers—the Nile, the Senegal, the Congo, and the Zambezi—were all sourced from the same great internal lake. The Portuguese were also told that the Mozambican Espirito Santo "river" (actually an estuary formed by the Umbeluzi, Matola, and Tembe Rivers) was sourced from a lake (hence its outlet became known as Delagoa Bay). As a result, several old maps depict the Zambezi and the "Espirito Santo" Rivers converging deep in the interior, at the same lake.

However, the Bisa-derived etymology is not without dispute. In 1845, W.D. Cooley, examining Pereira's notes, concluded the term "Zambezi" derives not from the Bisa people, but rather from the Bantu term "mbege"/"mbeze" ("fish"), and consequently it probably means merely "river of fish".[35] David Livingstone, who reached the upper Zambezi in 1853, refers to it as "Zambesi", but also makes note of the local name "Leeambye" used by the Lozi people, which he says means "large river or river par excellence". Livingstone records other names for the Zambezi—Luambeji, Luambesi, Ambezi, Ojimbesi, and Zambesi—applied by different peoples along its course, and asserts they "all possess a similar signification and express the native idea of this magnificent stream being the main drain of the country".[36]

In Portuguese records, the "Cuama River" term disappeared and gave way to the term "Sena River" (Rio de Sena), a reference to the Swahili (and later Portuguese) upriver trade station at Sena. In 1752, the Zambezi Delta, under the name "Rivers of Sena" (Rios de Sena) formed a colonial administrative district of Portuguese Mozambique, but common usage of "Zambezi" led eventually to a royal decree in 1858 officially renaming the district "Zambézia".

Exploration

The Zambezi region was known to medieval geographers as the Empire of Monomotapa, and the course of the river, as well as the position of lakes Ngami and Nyasa, were generally accurate in early maps. These were probably constructed from Arab information.[37]

The first European to visit the inland Zambezi River was the Portuguese degredado António Fernandes in 1511 and again in 1513, with the objective of reporting on commercial conditions and activities of the interior of Central Africa. The final report of these explorations revealed the importance of the ports of the upper Zambezi to the local trade system, in particular to East African gold trade.[38]

The first recorded exploration of the upper Zambezi was made by David Livingstone in his exploration from Bechuanaland between 1851 and 1853. Two or three years later, he descended the Zambezi to its mouth and in the course of this journey found the Victoria Falls. During 1858–60, accompanied by John Kirk, Livingstone ascended the river by the Kongone mouth as far as the falls, and also traced the course of its tributary the Shire and reached Lake Malawi.[37]

For the next 35 years, very little exploration of the river took place. Portuguese explorer Serpa Pinto examined some of the western tributaries of the river and made measurements of the Victoria Falls in 1878.[37] In 1884, Scottish-born Plymouth Brethren missionary Frederick Stanley Arnot traveled over the height of land between the watersheds of the Zambezi and the Congo and identified the source of the Zambezi.[39] He considered that the nearby high and cool Kalene Hill was a particularly suitable place for a mission.[40] Arnot was accompanied by Portuguese trader and army officer António da Silva Porto.[41]

In 1889, the Chinde channel north of the main mouths of the river was seen. Two expeditions led by Major A. St Hill Gibbons in 1895 to 1896 and 1898 to 1900 continued the work of exploration begun by Livingstone in the upper basin and central course of the river.[37]

Economy

The population of the Zambezi River Valley is estimated to be about 32 million. About 80% of the population of the valley is dependent on agriculture, and the upper river's floodplains provide good agricultural land.

Communities by the river fish it extensively, and many people travel from far afield to fish. Some Zambian towns on roads leading to the river levy unofficial "fish taxes" on people taking Zambezi fish to other parts of the country. Game fishing, as well as fishing for food, is a significant activity on some parts of the river. Between Mongu and Livingstone, several safari lodges cater to tourists who want to fish for exotic species, and many also catch fish to sell to aquaria.[42]

The river valley is rich in mineral deposits and fossil fuels, and coal mining is important in places. The dams along its length also provide employment for many people near them, in maintaining the hydroelectric power stations and the dams themselves. Several parts of the river are also very popular tourist destinations. Victoria Falls receives over 100,000 visitors annually, with 141,929 visitors reported in 2015.[43] Mana Pools and Lake Kariba also draw substantial tourist numbers.[44]

Transport

The river is frequently interrupted by rapids, so has never been an important long-distance transport route. David Livingstone's Zambezi expedition attempted to open up the river to navigation by paddle steamer, but was defeated by the Cahora Bassa rapids. Along some stretches, it is often more convenient to travel by canoe along the river rather than on the unimproved roads, which are often in very poor condition because they are regularly submerged in flood waters, and many small villages along the banks of the river are only accessible by boat.

In the 1930s and 40s, a paddle-barge service operated on the stretch between the Katombora Rapids, about 50 km (31 mi) upstream from Livingstone, and the rapids just upstream from Katima Mulilo. Depending on the water level, boats could be paddled through—Lozi paddlers, a dozen or more in a boat, could deal with most of them—or they could be pulled along the shore or carried around the rapids, and teams of oxen pulled barges 5 km (3.1 mi) over land around the Ngonye Falls.[45]

Road, rail, and other crossings of the river, once few and far between, are proliferating. They are, in order from the river's source:

- Cazombo road bridge, Angola, bombed in the civil war and not yet reconstructed[46]

- Chinyingi suspension footbridge near the town of Zambezi, a 300-metre (980 ft) footbridge built as a community project

- Lubosi Imwiko II Bridge linking the towns of Mongu and Kalabo, a 1,005 meter long concrete/steel road bridge including 38.5 km of embanked highway through Barotse Floodplain constructed between 2011 and 2016.[47][48] It is an extension of the Lusaka–Mongu Road, meant to be a connection between Lusaka and Angola.

- Sioma Bridge near the Ngonye Falls, anew 260 metres long road bridge (K 108 mln), opened in 2016 as part of the M10 Road (Sesheke - Senanga road).[49]

- Katima Mulilo road bridge, 900 metres (3,000 ft), between Namibia and Sesheke in Zambia, opened 2004, completing the Trans–Caprivi Highway connecting Lusaka in Zambia with Walvis Bay on the Atlantic coast

- Kazungula Bridge, opened in 2021, connecting Zambia and Botswana

- Victoria Falls Bridge (road and rail), the first to be built, completed in April 1905 and initially intended as a link in Cecil Rhodes' scheme to build a railway from Cape Town to Cairo: 250 metres (820 ft) long

- Kariba Dam carries the paved Kariba/Siavonga highway across the river

- Otto Beit Bridge at Chirundu, road, 382 metres (1,253 ft), 1939

- Second Chirundu Bridge, road, 400 metres (1,300 ft), 2002

- Tete Suspension Bridge, 1-kilometre (1,000 m) road bridge

- Dona Ana Bridge, railway bridge in Mozambique

- Caia Bridge, opened in 2009

A number of small ferries cross the river in Angola, western Zambia, and Mozambique, notably between Mongu and Kalabo. Above Mongu in years following poor rainy seasons, the river can be forded at one or two places. In tourist areas, such as Victoria Falls and Kariba, short-distance tourist boats take visitors along the river.

Ecology

Pollution

Sewage effluent is a major cause of water pollution around urban areas, as inadequate water-treatment facilities in all the major cities of the region release untreated sewage into the river. This has resulted in eutrophication of the river water and has facilitated the spread of diseases of poor hygiene such as cholera, typhus, and dysentery.[50]

Effects of dams

The construction of two major dams regulating the flow of the river has had a major effect on wildlife and human populations in the lower Zambezi region. When the Cahora Bassa Dam was completed in 1973, its managers allowed it to fill in a single flood season, going against recommendations to fill over at least two years. The drastic reduction in the flow of the river led to a 40% reduction in the coverage of mangroves, greatly increased erosion of the coastal region and a 60% reduction in the catch of prawns off the mouth because of the reduction in emplacement of silt and associated nutrients. Wetland ecosystems downstream of the dam shrank considerably. Wildlife in the delta was further threatened by uncontrolled hunting during the civil war in Mozambique.[51][52]

Conservation measures

The proposed Kavango–Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area was to cover parts of Zambia, Angola, Namibia, Zimbabwe, and Botswana, including the Okavango Delta in Botswana and Victoria Falls. Funding was boosted for cross-border conservation along the Zambezi in 2008. The project received a grant of €8 million from a German nongovernmental organisation. Part of the funds are to be used for research in areas covered by the project. However, Angola has warned that landmines from their civil war may impede the project.[53]

The river currently passes through Ngonye Falls National Park, Mosi-oa-Tunya National Park, and Lower Zambezi National Park (in Zambia), and the Zambezi National Park, Victoria Falls National Park, Matusadona National Park, Mana Pools National Park, and the Middle Zambezi Biosphere Reserve (in Zimbabwe).

Fish stocks management

As of 2017, the situation of overfishing in the upper Zambezi and its tributaries was considered dire, in part because of weak enforcement of the respective fisheries acts and regulations. The fish stocks of Lake Liambezi in the eastern Caprivi Strip were found to be depleted, and surveys indicated a decline in the whole Zambezi-Kwando-Chobe River system. Illegal fishing (by foreign nationals employed by Namibians) and commercially minded individuals, exploited the resources to the detriment of local markets and the communities whose culture and economy depend on these resources.[54]

Namibian officials have consequently banned monofilament nets and imposed a closing period of about 3 months every year to allow the fish to breed. They also appointed village fish guards and the Kayasa Channel in the Impalila conservancy area was declared a fisheries reserve. The Namibian ministry also promotes aquaculture and plans to distribute thousands of fingerlings to registered small-scale fish farmers of the region.[54]

Major towns

Along much of the river's length, the population is sparse, but important towns and cities along its course include:

- Katima Mulilo (Namibia)

- Livingstone, Mongu, Lukulu, Senanga and Sesheke (Zambia)

- Victoria Falls and Kariba (Zimbabwe)

- Songo and Tete (Mozambique)

- Cazombo (Angola)

See also

References

- "Richard Beilfuss & David dos Santos: Patterns of Hydrological Change in the Zambezi Delta, Monogram for the Sustainable Management of Cahora Bassa Dam and The Lower Zambezi Valley (2001). Estimated mean flow rate 3424 m³/s" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- International Network of Basin Organisations/Office International de L'eau: Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine "Développer les Compétences pour mieux Gérer l'Eau: Fleuves Transfrontaliers Africains: Bilan Global." (2002). Estimated annual discharge 106 km3, equal to mean flow rate 3360 m3/s

- "The Zambezi River Basin - A Multi Sector Investment Opportunities - Volume 4-Modelling, Analysis and Input Data" (PDF). June 2010.

- "Rivers Network". 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "Rivers Network". 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "Rivers Network". 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "Zambezi River | river, Africa". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "Zambezi River Facts and Information". www.victoriafalls-guide.net. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- "Chavuma Falls | waterfall, Zambia | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- "Zambia Tourism: Waterfalls". Zambia Tourism. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- Pasanisi, Francesco; Tebano, Carlo; Zarlenga, Francesco (March 2016). "A Survey near Tambara along the Lower Zambezi River". Environments. 3 (1): 6. doi:10.3390/environments3010006.

- "Zengamina Hydro Project | North West Zambia Development Trust". Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- "Dilapidated Zambezi Source Site Worry Ikelenge DC". muvitv.com. Muvi TV. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "ZM002 Source of the Zambezi". birdlife.org. Birdlife International. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- Dorling Kindersley, pp. 84–85

- Ashton, Peter; Love, David; Mahachi, Harriet; Dirks, Paul. "An Overview of the Impacts of Mining and Mineral Processing Operations on Water Resources and Water Quality in the Zambezi, Limpopo AND Olifant Catchments in Southern Africa" (PDF). International Institute for Environment and Development. Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development Project, Southern Africa. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- Page, Geology (25 November 2014). "Zambezi River". Geology Page. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "Zambezi River Facts and Information". www.victoriafalls-guide.net. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- Edington, Sean (29 December 2020). "Is rafting on the Zambezi River below The Victoria Falls Dangerous?". SAFPAR. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Valkenburgh, Blaire Van; White, Paula A. (20 April 2021). "Figure 1: Map showing location of Luangwa Valley and Greater Kafue Ecosystem in Zambia". PeerJ. 9: e11313. doi:10.7717/peerj.11313/fig-1.

- "GAZ Term "Zambezi River" (GAZ:00044898)". archive.gramene.org. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "Zambezi - Encyclopedia". theodora.com. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "River Discharge and Reservoir Storage Changes Using Satellite Microwave Radiometry".

- Knifton, Dulcie (July 2004). Revise AS Level Geography for Edexcel Specification B. Heinemann. ISBN 9780435101541.

- "Zambezi River Delta : Image of the Day". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 29 August 2013.

- "Zambezian coastal flooded savanna". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Richard Beilfuss & David dos Santos: Patterns of Hydrological Change in the Zambezi Delta, Mozambique. Archived 2 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine Working Paper No 2 Program for the Sustainable Management of Cahora Bassa Dam and The Lower Zambezi Valley (2001)

- Goudie, A.S. (2005). "The drainage of Africa since the Cretaceous". Geomorphology. 67 (3–4): 437–456. Bibcode:2005Geomo..67..437G. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2004.11.008.

- Moore, A.E. (1999). "A reapprisal of epeirogenic flexure axes in southern Africa". South African Journal of Geology. 102 (4): 363–376.

- AWF Four Corners Biodiversity Information Package No 2: Summary of Technical Reviews Archived 17 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 1 March 2007.

- Barros, Da Asia, Dec. I, Lib. X, vol. 2, p.374)

- Fr. J. dos Santos (1609), Ethiopia Oriental e varia historia de cousas Notaveis do Oriente, Pt. III. English translation is from Samuel Purchas's 1625 Haklyutus Posthumus, (1905) ed., Glasgow, vol. 10: p.220-21

- The connection between Santos/Monomatapa "Zambezi" and the "M'biza" is suggested in Cooley (1845).

- "Notícias dadas por Manoel Caetano Pereira, comerciante, que se entranhou pelo interior da África", as published in José Acúrsio das Neves (1830) Considerações Políticas e Comerciais sobre os Descobrimentos e Possessões na África e na Ásia. Lisbon: Imprensa Regia. p.373

- W.D. Cooley (1845) "The Geography of N'yassi, or the Great Lake of Southern Africa, investigated, with an account of the overland route from the Quanza in Angola to the Zambezi in the government of Mozambique", Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, p.185-235.

- David Livingstone (1857) Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (p.208)

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cana, Frank (1911). "Zambezi". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 951–953.

- Newitt, Malyn (2005). A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400-1668. Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 0-203-32404-8.

- Howard, Dr. J. Keir (2005). "Arnot, Frederick Stanley". Dictionary of African Christian Biography. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- Pritchett, James Anthony (2007). Friends for life, friends for death: cohorts and consciousness among the Lunda-Ndembu. University of Virginia Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0-8139-2624-7.

- Fish, Bruce; Fish, Becky Durost (2001). Angola, 1880 to the present: slavery, exploitation, and revolt. Infobase Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 0-7910-6197-3.

- "The Zambezi River, Drained Bone Dry". International Rivers. 30 November 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Archived 25 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine Republic of Zambia Ministry of Tourism and Arts 2015 Tourism Statistical Digest

- "Hydroelectric Power: Advantages of Production and Usage". www.usgs.gov. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- E. C. Mills: "Overlanding Cattle from Barotse to Angola", The Northern Rhodesia Journal, Vol 1 No 2, pp 53–63 (1950). Accessed 16 December 2017.

- Visible on Google Earth at latitude -11.906 longitude 22.831.

- Visible on Google Earth at longitude 22.924 latitude -15.214.

- "Mongu-Kalabo Road - Zambia's Engineering Marvel". zedcorner.com. 13 April 2016. Archived from the original on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- "President launches K108m Sioma Bridge – Zambia Daily Mail". daily-mail.co.zm. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Herbig, Friedo J. W. (1 January 2019). Meissner, Richard (ed.). "Talking dirty - effluent and sewage irreverence in South Africa: A conservation crime perspective". Cogent Social Sciences. 5 (1): 1701359. doi:10.1080/23311886.2019.1701359.

- "Zambezi River Tourist Information". www.touristlink.com. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- Isaacman, Allen; Sneddon, Chris (2000). "Toward a Social and Environmental History of the Building of Cahora Bassa Dam". Journal of Southern African Studies. 26 (4): 597–632. doi:10.1080/713683608. ISSN 0305-7070. JSTOR 2637563. S2CID 153574634.

- "Sub-Saharan Africa news in brief: 13–25 March".

- Kooper, Lugeretzia (23 June 2017). "Zambezi fishermen warned against overfishing". namibian.com.na. The Namibian. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- "Zambia warns against fish killed by mysterious disease". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009.

Further reading

- Bento C.M., Beilfuss R. (2003), Wattled Cranes, Waterbirds, and Wetland Conservation in the Zambezi Delta, Mozambique, report for the Biodiversity Foundation for Africa for the IUCN - Regional Office for Southern Africa: Zambezi Basin Wetlands Conservation and Resource Utilisation Project.

- Bourgeois S., Kocher T., Schelander P. (2003), Case study: Zambezi river basin, ETH Seminar: Science and Politics of International Freshwater Management 2003/04

- Davies B.R., Beilfuss R., Thoms M.C. (2000), "Cahora Bassa retrospective, 1974–1997: effects of flow regulation on the Lower Zambezi River," Verh. Internat. Verein. Limnologie, 27, 1–9

- Dunham KM (1994), The effect of drought on the large mammal populations of Zambezi riverine woodlands, Journal of Zoology, v. 234, p. 489–526

- Dorling Kindersley Publishing, Inc. (2004). World reference atlas. New York: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7566-0481-8

- Wynn S. (2002), "The Zambezi River - Wilderness and Tourism", International Journal of Wilderness, 8, 34.

- H. C. N. Ridley: "Early History of Road Transport in Northern Rhodesia", The Northern Rhodesia Journal, Vol 2 No 5 (1954)—Re Zambezi River Transport Service at Katombora.

- Funding boost for cross-border conservation project

External links

- Information and a map of the Zambezi's watershed

- Zambezi Expedition - Fighting Malaria on the "River of Life" Archived 7 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Home Page". Zambezi River Authority. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- The Zambezi Society

- Map of Africa's river basins

- Bibliography on Water Resources and International Law Archived 9 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine Peace Palace Library

- The Nature Conservancy's Great Rivers Partnership works to conserve the Zambezi River