Zeth Höglund

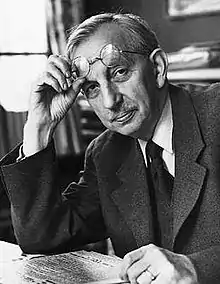

Carl Zeth "Zäta" Konstantin Höglund (29 April 1884 – 13 August 1956) was a leading Swedish communist politician, anti-militarist, author, journalist and mayor (finansborgarråd) of Stockholm (1940–1950).

Zeth Höglund | |

|---|---|

Zeth Höglund in 1953 | |

| Leader of the Communist Party of Sweden | |

| In office 1917–1918 | |

| Preceded by | Position created |

| Succeeded by | Ernst Åström & Karl Kilbom |

| In office 1919–1920 | |

| In office 1921–1923 | |

| In office 1923–1924 | |

| Preceded by | Zeth Höglund |

| Succeeded by | Nils Flyg & Karl Kilbom |

| Leader of the Social Democratic Youth League (SDUF) | |

| In office 1909–1921 | |

| Preceded by | Per Albin Hansson |

| Succeeded by | Nils Flyg |

| Member of the Riksdag's Second Chamber | |

| In office 1909–1921 | |

| In office 1929–1940 | |

| 5th Mayor of Stockholm | |

| In office 1 October 1940 – 15 October 1950 | |

| Monarch | Gustaf V |

| Preceded by | Halvar Sundberg |

| Succeeded by | John Bergvall |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Carl Zeth Konstantin Höglund 29 April 1884 Örgryte parish, Gothenburg Municipality, Västra Götaland County, Sweden |

| Died | 13 August 1956 (aged 72) Västerleds parish, Stockholm Municipality, Stockholm County, Sweden |

| Resting place | Skogskyrkogården |

| Political party | Social Democratic Party, Sweden's Social Democratic Left Party/ Communist Party |

| Other political affiliations | Communist Party, the Höglund-branch |

| Profession | Politician |

Höglund can be credited as the founder of the Swedish Communist movement. Zeth Höglund went on many meetings in Bolshevik Russia and was elected to the Comintern Executive Committee in 1922. In 1926, he returned to the Social Democratic party but still chose to define himself as a communist.

Biography

Early years

Zeth Höglund grew up in Gothenburg in a lower-middle-class family. His father, Carl Höglund, worked as a merchant in leather and later became a shoemaker. Zeth was the youngest of ten children. He was also the only son, and hence had nine big sisters.

His parents were very religious but disliked the church hierarchy and the way preachers and governments used religion to influence people. Höglund would later become an atheist.

Political awakening

Early on in high school, Höglund started considering himself a socialist and instead of his school books he started reading the German socialists Karl Marx, Ferdinand Lassalle, Wilhelm Liebknecht and the Swedish socialists Axel Danielsson and Hjalmar Branting. He also read Nietzsche and August Strindberg.

He graduated from high school in 1902 with average grades. He soon got an internship with the liberal daily Göteborgs-Posten and was hired by that newspaper that fall.

The same fall Höglund started studying History, Political Science and Literature at the Gothenburg University. Here he met Fredrik Ström, a four-year-older student, also a radical socialist. They developed a close friendship that would last their whole lives.

At the May Day demonstration in 1903, Höglund and Fredrik Ström had an invitation to speak from the Social Democratic Party on a demand for 8-hour workdays. Höglund started and was followed by Ström, who suddenly started agitating for 6-hour workdays, and even promising 4-hour workdays in a socialist future.

In Paris

In the summer of 1903, Höglund and Fredrik Ström decided to move to Paris. They were curious of the homeland of the great French Revolution of 1789 and the city where their heroes Jean-Paul Marat, Georges Danton and Louis de Saint-Just had lived and fought.

In Paris they attended several socialist meetings, of which the grandest was when Jean Jaurès spoke to over 4,000 people. They tried to write on their own and sent political articles home to Sweden where some of them were published in different newspapers. One day at the post office, Fredrik Ström discovered that they were under surveillance by the French police.

The two Swedes were very short on money. They had to live modestly in Paris and could spend little money on food. When winter came they froze and went hungry. They had hoped to stay much longer, but decided to go back to Sweden. They had no funds for the trip home, but two of Höglund's sisters, Ada and Alice, sent them the money, and they returned home by Christmas 1903.

Swedish Social Democratic Party

Höglund joined the Swedish Social Democratic Party in 1904 and became the leader of party's youth movement. He wrote an article called "Let Us Make Swedish Social Democracy the Strongest in the World".

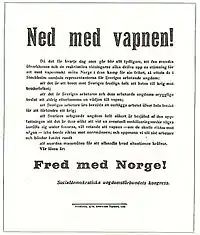

In 1905, Höglund strongly supported Norway's right to self-determination and independence from Sweden. When the Swedish conservatives made clear that they were prepared to subdue Norway by force, Zeth Höglund wrote the manifesto Down With Weapons! (Ned med vapnen!) in which he indirectly declared that if the Swedish workers were forced to go to war with Norway, they would instead turn their weapons against the Swedish ruling class. The war was avoided, and Norway became independent, but, as a result of his anti-war agitation, Zeth Höglund was sentenced to six months in jail, which he served between the mid-summer and Christmas of 1906.

In 1908 Höglund was instrumental in the establishment of a weekly communist journal entitled Stormklockan which he edited.[1]

While condemned and imprisoned by the Swedish ruling class as a dangerous rebel, Höglund was saluted by others. The German socialist Karl Liebknecht described him as a hero in his book Militarism and Anti-Militarism. The Russian Communist leader Lenin wrote: "The close alliance between the Norwegian and Swedish workers, their complete fraternal class solidarity, gained from the Swedish workers' recognition of the right of the Norwegians to secede.... The Swedish workers have proved that in spite of all the vicissitudes of bourgeois policy.... they will be able to preserve and defend the complete equality and class solidarity of the workers of both nations in the struggle against both the Swedish and the Norwegian bourgeoisie." (The Right of Nations to Self-Determination)

In November 1912, Höglund, together with his Swedish friends Hjalmar Branting and Ture Nerman, attended the special emergency convention of the Socialist International, which had been summoned to Basel in Switzerland, due to the outbreak of the Balkan Wars. At the convention, the leaders of all the European Socialist parties agreed to stand together internationally to prevent any future wars.

Together with Fredrik Ström and Hannes Sköld, Höglund wrote the anti-militarist manifesto Det befästa fattighuset (The Fortress Poorhouse) in which they described and criticized Sweden as an armed fortress and at the same time a poorhouse, where the people were miserable and the rulers spent all resources on militarism. Not one krona, not one öre, to militarism! was the slogan of the manifesto. It was despised from the bourgeoisie politicians and media.

World War I and Zimmerwald

In 1914, Höglund got a seat in the lower house of the Riksdag. There, he agitated for socialism, against capitalism, war and the Swedish monarchy. Höglund's speeches were so revolutionary that they even provoked Hjalmar Branting, although many young socialists started seeing Höglund as their true leader.

In 1914, when World War I broke out, Zeth Höglund together with Ture Nerman represented the Swedish-Norwegian members of the Zimmerwald Conference, the international socialist anti-war movement which gathered in the small Swiss village of Zimmerwald. There the young Swedish socialist met Vladimir Lenin, Grigory Zinoviev, Vatslav Vorovsky, Karl Radek and Leon Trotsky: Zeth Höglund and Ture Nerman felt very close to the Russian Bolsheviks.

Back in Bern, after the conference in Zimmerwald, Zeth Höglund had a beer with Lenin in a local pub. Lenin asked Höglund if the Swedish Socialist Youth Organization possibly could donate some much needed money to the Bolsheviks. Höglund offered Lenin some money, and although it was a small amount, Lenin was extremely joyful and grateful. Höglund realized afterwards that maybe it was more about political trust than money.

Even though Sweden did not participate in the war, Höglund's anti-war propaganda was enough to send Höglund to jail again for "betrayal of the Kingdom." While Höglund was at Långholmen prison, in Stockholm, his wife gave birth to their second daughter.

In April 1917, Lenin and other communists passed through Stockholm from the exile in Switzerland on their return trip to Russia after the February Revolution. Lenin, who was greeted in Sweden by Otto Grimlund, Ture Nerman, Fredrik Ström and Carl Lindhagen, wanted to go and visit Höglund in jail. Arrangements were made, but, due other meetings running over time and the Bolsheviks hurry to get back to Russia, Lenin's visit to Långholmen had to be cancelled. However, the Bolshevik leader sent a telegram to Höglund wishing him strength and hoping to see him soon again, signed Lenin and Ström.

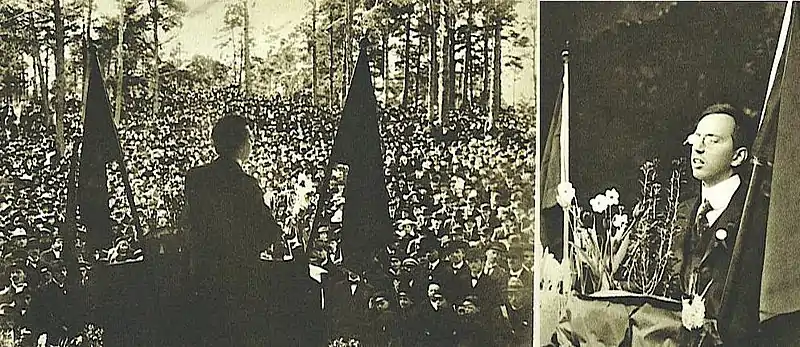

Zeth Höglund, prisoner number 172, was released from Långholmen prison on 6 May 1917 after more than 13 months in prison. He was greeted by his friends, family and a couple of thousands workers who had gathered outside the prison. On the same day of his release, Höglund held a speech in a park in Stockholm, massing thousands of people to hear him talk about peace, socialism and revolution.

From Russia came a telegram: "On the day of your release from prison, the C.C. of the R.S.D.L.P. greets in your person a staunch fighter against the imperialist war and a wholehearted supporter of the Third International." signed by Lenin and Zinoviev.

Birth of the Swedish Communist Movement

Höglund was a radical, revolutionary socialist and was the main leader of the Left Opposition in the Social Democratic Party, against the reformist politics of the party leader Hjalmar Branting. In 1917, Zeth Höglund and the left-wing were expelled from the party but they regrouped as the Swedish Social Democratic Left Party, which supported the Bolsheviks in Russia and worked for the aim of a communist revolution in Sweden. This new party would soon become the (original) Communist Party of Sweden (SKP) and still exists today as the Left Party.

In 1916, the left socialists launched their own newspaper, Politiken, in which they wrote and published many texts by Lenin, Zinoviev, Bukharin and Karl Radek. Both Radek and Bukharin, who spent a lot of time in the neutral Sweden during the World War, had a great influence on the development of the Swedish Socialist Left.

In December 1917, Höglund and Karl Kilbom traveled to Petrograd to visit the Bolsheviks and show their support of the revolution. On their day of arrival, Höglund was invited to see Lenin in the Smolny. Lenin was in an excellent mood. The Swedish communists were one of the first international groups to visit Soviet Russia and, by New Year's Eve, the Swedish delegation was joined by Otto Grimlund and Carl Lindhagen. Höglund and Lindhagen were invited to speak to an audience of 10,000 people in Petrograd. The Bolshevik Alexandra Kollontay, who had spent a lot of time in Scandinavia and had become a close friend of the Swedish left socialists, translated the speeches of Lindhagen and Höglund from Swedish to Russian.

Höglund stayed until spring of 1918 in Soviet Russia. He traveled around the country and worked closely with the Bolshevik leaders. He was even offered to be made an honorable corporal in the Red Army, but he declined. (The position was then offered to the Norwegian Communist Olav Scheflo.) Höglund wrote long texts for Politiken and managed to keep a great influence over the communist movement in Sweden from abroad.

On his way back to Sweden, Höglund also visited the Reds in Finland, which at the time was in the throes of the Finnish civil war, which soon ended in White victory.

Comintern

In March 1919, the founding congress of the Communist International (Comintern) took place in Russia, with Otto Grimlund representing the Swedish Socialist Left. Zeth Höglund worked hard to convince his friends that the Swedish Party should join the Comintern.

During the 2nd World Congress of the Comintern, which took place in Russia the summer of 1920, Zinoviev said, "Unfortunately Comrade Höglund and others who took part along with us in the founding of the Communist International are not here." Instead, Kata Dalström represented the Swedish communists.

But in the summer of 1921, Zeth Höglund, together with Fredrik Ström and Hinke Bergegren, represented Sweden in the third congress of the Comintern held in Moscow, and Höglund worked hard to make the Swedish party accept the Twenty-one Conditions for membership in the Communist International, including changing the name from Sweden's Social Democratic Left Party to the Swedish Communist Party. Some of the party's members who did not agree to the 21 theses left the party while others, including Carl Lindhagen, were expelled.

Höglund was elected to the Comintern Executive Committee in 1922. However, in 1924, over disagreement concerning the development of Comintern policies, thinking there was too much direct control from Moscow, Höglund split from Swedish Communist Party and founded his own Communist Party. In 1926 he rejoined the Swedish Social Democratic Party, where he was part of the radical left. He still considered himself a Communist until the day he died in 1956, always defending the original ideas of Lenin.

Zeth Höglund was the Mayor of Stockholm from 1940 to 1950.

Zeth Höglund had a street named after him in Leningrad, now Saint Petersburg.

Works

- Zeth Höglund is the author of a two-volume biography about Hjalmar Branting.

- His own autobiography is called Minnen i fackelsken (Memories in Torch Light) and is in three volumes: Part I: Glory Days, 1900–1911, Part II: From Branting to Lenin, 1912 – 1916, and Part III, The Revolutionary Years, 1917–1921.

- Zeth's daughter, Gunhild Höglund completed a fourth volume in the Memories in Torch Light series, called Moscow, There and Back Again, published in 1960.

Footnotes

- Kristin Ewins (April 2017). "Swedish communism in print, 1917–45". Twentieth Century Communism: A Journal of International History. 12 (12): 200–234.

Further reading

Media related to Zeth Höglund at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Zeth Höglund at Wikimedia Commons- Kan, Aleksander. Hemmabolsjevikerna. Falun: Carlssons bokförlag, 2005.

- Höglund, Zeth. Glory Days, 1900–1911. (autobiography vol. 1.) Stockholm: Tidens förlag, 1951.

- Höglund, Zeth. From Branting to Lenin, 1912 – 1916. (autobiography vol. 2.) Stockholm: Tidens förlag, 1953.

- Höglund, Zeth. The Revolutionary Years, 1917–1921. (autobiography vol. 3.) Stockholm: Tidens förlag, 1956.

- Lenin's Struggle for a Revolutionary International – Documents, 1907–1916: The Preparatory Years, New York: Pathfinder Press, 1986.

- Founding the Communist International – Proceedings and Documents of the First Congress, March 1919, New York: Pathfinder Press, 1987.