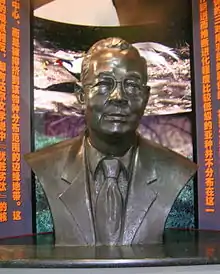

Tso-hsin Cheng

Tso-hsin Cheng (郑作新 also transcribed as Zheng Zuoxin) (18 November 1906 – 27 June 1998) was a Chinese ornithologist known for his seminal work on the birds of China and mentoring a generation of researchers. Educated in the United States, he chose to stay in China after the Second World War while many of his academic colleagues moved to Taiwan. He was severely punished during the Cultural Revolution despite being a member of the Communist Party.

Biography

Early life

Cheng was born in Fujian on November 18, 1906, and grew up with an interest in the local birds. His mother died of tuberculosis when he was very young and he was taken care of mostly by his grandmother. His father was one of the few Chinese with a higher education and knew English. His father taught him to speak English. As a young boy he was weak and his father encouraged the boy to take up sports. Cheng hiked in the mountains, played tennis and even became a champion 100 m sprinter. His early naturalist interests were in the nature of culinary objects. He collected fish, wild fruit and vegetables which his grandmother cooked. He went to the high school at Fuzhou and sought admission to the Fujian Christian University at the age of 15 which required him to undergo a special test. The English professor of biology there asked the applicants about which vegetable had the highest vitamins and he was the only one to come up with the answer as tomato. Tomatoes were then unheard of in China but Cheng had read about them, leading to his being admitted. He graduated in 1926 after seven semesters after which he wished to move to the United States.[1]

USA

An uncle who was a doctor in Fuzhou funded Cheng's travel and he chose the University of Michigan as a cousin studied there. He studied under Peter Olas Okkelberg and received a doctorate in 1930 for his thesis on "The Germ Cell history of Rana cantabrigensis Baird". He also received a Sigma Xi golden Key award. While in the US he had visited the natural history museum of the university and encountered a golden pheasant specimen. He wondered why all the species in China in recent times were described by non-Chinese. He also knew of 3000-year-old classical Chinese literature which had described one-hundred bird species. He chose to return to China and rejected offers to work in the United States.[1]

China

Returning to China in 1930 he joined the Fujian Christian University and later founded the China Zoological Society, while heading the department of biology at Fuzhou. In 1938 his university moved to Shao-wu due to the threat of the Japanese invasion. He moved to the US in April 1945 to work on Chinese ornithology, examining specimens in museums and universities across America. He returned to Fuzhou in September 1946. In 1947 he was forced to move to Nanjing due to civil war between Maoists and the Kuomintang. In 1948 many university staff fled to Taiwan and Cheng also considered fleeing. He however asked around and was told that the communist party needed scientists. He then remained and joined the Communist Party. In 1950 he moved to Beijing and became a curator of birds at the Academia Sinica and founded the Peking Natural History Museum in 1951. He was the first director of the scientific publications office. He translated Joachim Steinbacher's book on bird migration and ornithology into Chinese. From 1955 to 1957 he worked along with Soviet and East German ornithologists in expeditions and studies in southern Yunnan and northeastern China.[1]

Cultural Revolution

In 1958 Cheng's work in China was interrupted by a campaign to eradicate sparrows (along with mice, flies and mosquitoes). Cheng was, for ecological reasons, against the campaign from the start but it was only in 1959 that he could influence a decision against the killing of sparrows. He travelled to East Germany in May 1957 and worked with Erwin Stresemann examining specimens from the Chinese region. He was also able to meet other ornithologists like L A Portenko, Charles Vaurie, and Gunther Niethammer in meetings that Stresemann called as the "Atlantic Pacific Conference". He was however not allowed to attend evening parties at Stresemann's home in West Berlin due to instructions from the Chinese embassy in East Germany. Cheng was made a foreign correspondent of the German Ornithologists' Society through the nomination of Stresemann. Cheng returned to China with stays in Leningrad and Moscow. Returning to China he was faced by Mao's Cultural Revolution.[1]

Scientific work came to a halt and a slogan was that "the more knowledge you possess, the more revolutionationary you are". Cheng was declared a criminal as he had opposed Chairman Mao's campaign against sparrows. He was told that "birds are public animals of capitalism" and had to wear a badge that read "reactionary" and made to undergo an examination of his supposed ornithological training apart from being forced to sweep the corridors and clean toilets. The test was given by a committee and he was asked to identify a bird made up of parts from multiple species.[1] After failing the "test", his salary was reduced to a bare minimum. In August 1966 he was kept in isolation in a cowshed for six months and his house was searched by Red Guards who confiscated all his belongings including a typewriter that he valued the most. The Academia Sinica was occupied by the Red Guards from 1967 until 1968 when Mao ordered their removal. Peace returned only in the 1970s and his work on the birds of China was sent for publication after having been rejected once earlier. It was published in 1978, but dated as 1976, and he was forced to include a long quotation from Mao, who had since died. After Mao's death, Cheng was invited to an international symposium of the World Pheasant Association in November 1978. He also spent two months in England during which time he met Sir Peter Scott and G.V.T.Matthews. He served as a professor at the Beijing Normal University and in 1987 he and his colleagues published a Synopsis of the Avifauna of China. He also edited the Fauna Sinica, Aves volumes from 1970 to 1980. He worked on bird conservation and worked on international collaboration for the protection of migratory species.[2][3][1][4]

Personal life

Cheng met Chen Jia-jang (Lydia) while playing tennis and married her in 1942. In 1992 the couple celebrated their golden anniversary with Cheng gifting the golden key from Michigan to his wife and receiving in turn a gift of a golden pencil.[1]

Honours

Cheng died from a heart attack in 1998. Several species have been named in his honour including Cheng's jird (Meriones chengi) Wang, 1964. Pamela Rasmussen named the Sichuan bush warbler (Locustella chengi) discovered in 2015 after Professor Cheng.[1][5]

References

- Nowak, Eugeniusz (2002). "Erinnerungen an Ornithologen, die ich kannte (4. Teil)" (PDF). Der Ornithologische Beobachter (in German). 99: 49–70. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2019.

- "Obituary". Ibis. 141: 167. 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1999.tb04279.x.

- Hsu, Weishu (1999). "In memoriam: Tso-Hsin Cheng, 1906-1998" (PDF). The Auk. 116 (2): 539–541. doi:10.2307/4089387. JSTOR 4089387.

- Grimm, Robert J. (1979). "Ornithology in the People's Republic Of China (PRC)" (PDF). Condor. 81: 104–109. doi:10.2307/1367873. JSTOR 1367873.

- Alström, Per; Xia, Canwei; Rasmussen, Pamela C; Olsson, Urban; Dai, Bo; Zhao, Jian; Leader, Paul J; Carey, Geoff J; Dong, Lu; Cai, Tianlong; Holt, Paul I; Le Manh, Hung; Song, Gang; Liu, Yang; Zhang, Yanyun; Lei, Fumin (2015). "Integrative taxonomy of the Russet Bush Warbler Locustella mandelli complex reveals a new species from central China" (PDF). Avian Research. 6. doi:10.1186/s40657-015-0016-z. S2CID 18977782.