Guatemala City

Guatemala City (Spanish: Ciudad de Guatemala), formally New Guatemala of Assumption and the Ancient (Spanish: Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción y la Antigua),[4] known locally as Guate, is the capital and largest city of Guatemala,[5] and the most populous urban area in Central America. The city is located in the south-central part of the country, nestled in a mountain valley called Valle de la Ermita (English: Hermitage Valley). The city is also the capital of the Guatemala Department.

Guatemala City

Ciudad de Guatemala | |

|---|---|

| New Guatemala of Assumption and the Ancient Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción y la Antigua | |

Clockwise from top: Zone 10 skyline; Supreme Court of Justice; Ciudad Cayalá; Cultural Center of Spain; Guatemala National Palace; Torre del Reformador; Zone 14; and Guatemala City Cathedral | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Motto(s): "Todos somos la ciudad" (We are all the city), "Tú eres la ciudad" (You are the city). | |

Interactive map outlining Guatemala City | |

Guatemala City Location within Guatemala [1]  Guatemala City Guatemala City (Central America)  Guatemala City Guatemala City (America) .svg.png.webp) Guatemala City Guatemala City (Earth) | |

| Coordinates: 14°36′48″N 90°32′7″W | |

| Country | Guatemala |

| Department | Guatemala Department |

| Established | 1776 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • Mayor | Ricardo Quiñónez Lemus (Unionist) |

| Area | |

| • Capital city | 997 km2 (385 sq mi) |

| • Water | 0 km2 (0 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,500 m (4,900 ft) |

| Population (2018) | |

| • Capital city | 923,392 [2] |

| • Estimate (2020) | 994,938 [3] |

| • Density | 4,722.76/km2 (12,231.9/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 3 046 252 [3] |

| Time zone | UTC−06:00 (Central America) |

| Climate | Aw |

| Website | www |

Guatemala City is the site of the Mayan city of Kaminaljuyu, founded around 1500 BC. Following an earthquake in La Antigua in 1776 it was made capital of the Captaincy General of Guatemala. In 1821, Guatemala City was the scene of the declaration of independence of Central America from Spain, after which it became the capital of the newly established United Provinces of Central America (later the Federal Republic of Central America).[6]

In 1847, Guatemala declared itself an independent republic, with Guatemala City as its capital. The capital was originally located in what is now Antigua Guatemala, and was moved to its current location in 1777.[7]

Guatemala City and the original location in Antigua Guatemala were almost completely destroyed by the 1917–18 earthquakes. Reconstructions following the earthquakes have resulted in a more modern architectural landscape. Today, Guatemala City is the political, cultural, and economic center of Guatemala.

History

Early history

Human settlement on the present site of Guatemala City began with the Maya, who built a large ceremonial center at Kaminaljuyu. This large Maya settlement, the biggest outside the Maya lowlands in the Yucatán Peninsula, rose to prominence around 300 BC due to an increase in mining and trading of obsidian, a valuable commodity for the pre-Columbian civilizations in Mesoamerica. Kaminaljuyu then collapsed around 300 AD for unknown causes.[8]

After a series of devastating earthquakes had left the old capital city, Antigua Guatemala, in ruins and unusable to the Spanish colonial authorities. During this period the central plaza, with the Cathedral of Guatemala City and the Palace of the Captain-General, were constructed. After Central American independence from Spain the city became the capital of the United Provinces of Central America in 1821.

The 19th century saw the construction of the monumental Carrera Theater in the 1850s, and the modern-day Presidential Palace in the 1890s. At this time the city was expanding around the 30 de Junio Boulevard and elsewhere, displacing native settlements on the peripheries of the growing city. Earthquakes in 1917–1918 destroyed many historic structures. Under President Jorge Ubico in the 1930s a hippodrome and many new public buildings were constructed, although slums that had formed after the 1917–1918 earthquakes continued to lack basic amenities.

Guatemala City continues to be subject to natural disasters, with the latest being the two disasters that struck in May 2010: the eruption of the Pacaya volcano and, two days later, the torrential downpours from Tropical Storm Agatha.

Contemporary history

Guatemala City serves as the economic, governmental, and cultural epicenter of the nation of Guatemala. The city also functions as Guatemala's main transportation hub, hosting an international airport, La Aurora International Airport, and serving as the origination or end points for most of Guatemala's major highways. The city, with its robust economy, attracts hundreds of thousands of rural migrants from Guatemala's interior hinterlands and serves as the main entry point for most foreign immigrants seeking to settle in Guatemala.

In addition to a wide variety of restaurants, hotels, shops, and a modern BRT transport system (Transmetro), the city is home to many art galleries, theaters, sports venues and museums (including some fine collections of Pre-Columbian art) and provides a growing number of cultural offerings. Guatemala City not only possesses a history and culture unique to the Central American region, it also furnishes all the modern amenities of a world class city, ranging from an IMAX Theater to the Ícaro film festival (Festival Ícaro), where independent films produced in Guatemala and Central America are debuted.

Structure and growth

Guatemala City is located in the mountainous regions of the country, between the Pacific coastal plain to the south and the northern lowlands of the Peten region.

The city's metropolitan area has recently grown very rapidly and has absorbed most of the neighboring municipalities of Villa Nueva, San Miguel Petapa, Mixco, San Juan Sacatepequez, San José Pinula, Santa Catarina Pinula, Fraijanes, San Pedro Ayampuc, Amatitlán, Villa Canales, Palencia, and Chinautla, forming what is now known as the Guatemala City Metropolitan Area.

The city is subdivided into 22 zones ("Zonas") designed by the urban engineering of Raúl Aguilar Batres, each one with its own streets ("Calles"), avenues ("Avenidas") and, sometimes, "Diagonal" Streets, making it pretty easy to find addresses in the city. Zones are numbered 1–25, with Zones 20, 22 and 23 not existing as they would have fallen in two other municipalities' territory.[9] Addresses are assigned according to the street or avenue number, followed by a dash and the number of metres it is away from the intersection.[10]

For example, the INGUAT Office on "7a Av. 1-17, Zona 4" is a building which is located on Avenida 7, 17 meters away from the intersection with Calle 1, toward Calle 2 in zone 4.

7a Av. 1-17, Zona 4; and 7a Av. 1-17, Zona 10, are two radically different addresses.

Short streets/avenues do not get new sequenced number, for example, 6A Calle is a short street between 6a and 7a.

Some "avenidas" or "Calles" have a name in addition to their number, if it is very wide; for example, Avenida la Reforma is an avenue which separates Zone 9 and 10, and Calle Montúfar is Calle 12 in Zone 9.

Calle 1 Avenida 1 Zona 1 is the center of every city in Guatemala.

Zone One is the Historic Center (Centro Histórico), lying in the very heart of the city, the location of many important historic buildings, including the Palacio Nacional de la Cultura (National Palace of Culture), the Metropolitan Cathedral, the National Congress, the Casa Presidencial (Presidential House), the National Library, and Plaza de la Constitución (Constitution Plaza, old Central Park). Efforts to revitalize this important part of the city have been undertaken by the municipal government.

Besides the parks, the city offers a portfolio of entertainment in the region, focused on the so-called Zona Viva and the Calzada Roosevelt, as well as four degrees North. Casino activity is considerable, with several located in different parts of the Zona Viva. The area around the East market is being redeveloped.

Within the financial district are the tallest buildings in the country, including: Club Premier, Tinttorento, Atlantis building, Atrium, Tikal Futura, Building of Finances, Towers Building Batteries, Torres Botticelli, Tadeus, building of the INTECAP, Royal Towers, Towers Geminis, Industrial Bank towers, Holiday Inn Hotel, Premier of the Americas, among many others to be used for offices, apartments, etc. Also included are projects such as Zona Pradera and Interamerica's World Financial Center.

One of the most outstanding mayors was the engineer Martin Prado Vélez, who took over in 1949, and ruled the city during the reformist Presidents Juan José Arévalo and Jacobo Arbenz Guzman, although he was not a member of the ruling party at the time and was elected due his well-known capabilities. Of cobanero origin, married with Marta Cobos, he studied at the University of San Carlos; under his tenure, among other modernist works of the city, infrastructure projects included El Incienso bridge, the construction of the Roosevelt Avenue, the main road axis from East to West of the city, the town hall building, and numerous road works which meant the widening of the colonial city, its order in the cardinal points and the generation of a ring road with the first cloverleaf interchange in the city.[11]

In an attempt to control the rapid growth of the city, the municipal government (Municipalidad de Guatemala), headed by longtime Mayor Álvaro Arzú, has implemented a plan to focus growth along important arterial roads and apply Transit-oriented development (TOD) characteristics. This plan, denominated POT (Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial), aims to allow taller building structures of mixed uses to be built next to large arterial roads, and gradually decline in height and density moving away from such. It is also worth mentioning, that due to the airport being in the south of the city, height limits based on aeronautical considerations have been applied to the construction code. This limits the maximum height for a building, at 60 metres (200 feet) in Zone 10, up to 95 metres (312 feet) in Zone 1.[9]

Climate

Despite its location in the tropics, Guatemala City has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw) bordering humid subtropical climate (Cwa), due to its relatively high altitude which moderate the average temperatures. Guatemala City is generally very warm, almost springlike, throughout the course of the year.

It occasionally gets hot during the dry season, but not as hot and humid as in Central American cities at sea level. The hottest month is April. The rainy season extends from May to October, coinciding with the tropical storm and hurricane season in the western Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, while the dry season extends from November to April. The city can at times be windy, which also leads to lower ambient temperatures.

The city's average annual temperature ranges are 22–28 °C (71.6–82.4 °F) during the day and 12–17 °C (53.6–62.6 °F) at night; its average relative humidity is 82% in the morning and 58% in the evening; and its average dew point is 16 °C (60.8 °F).[12]

| Climate data for Guatemala City (1990-2011) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.0 (86.0) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.9 (93.0) |

31.2 (88.2) |

29.1 (84.4) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.8 (85.6) |

28.6 (83.5) |

29.9 (85.8) |

28.8 (83.8) |

33.9 (93.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 24.3 (75.7) |

25.8 (78.4) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.1 (80.8) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.1 (77.2) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.2 (75.6) |

23.9 (75.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 18.7 (65.7) |

19.7 (67.5) |

20.7 (69.3) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.3 (70.3) |

20.8 (69.4) |

21.0 (69.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

20.3 (68.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.8 (65.8) |

20.4 (68.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 13.2 (55.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

16.8 (62.2) |

16.3 (61.3) |

16.5 (61.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

16.0 (60.8) |

14.7 (58.5) |

13.7 (56.7) |

15.4 (59.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

7.8 (46.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

8.6 (47.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

13.5 (56.3) |

13.0 (55.4) |

11.4 (52.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

7.6 (45.7) |

6.0 (42.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 2.8 (0.11) |

5.4 (0.21) |

6.0 (0.24) |

31.0 (1.22) |

128.9 (5.07) |

271.8 (10.70) |

202.6 (7.98) |

202.7 (7.98) |

236.6 (9.31) |

131.6 (5.18) |

48.8 (1.92) |

6.6 (0.26) |

1,274.8 (50.18) |

| Average rainy days | 1.68 | 1.45 | 2.00 | 4.73 | 12.36 | 21.14 | 18.59 | 19.04 | 20.82 | 14.59 | 6.18 | 2.64 | 125.22 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.3 | 73.4 | 73.2 | 74.3 | 77.3 | 82.4 | 80.8 | 80.9 | 84.5 | 82.0 | 79.2 | 76.0 | 77.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 248.4 | 236.2 | 245.6 | 237.9 | 184.4 | 155.3 | 183.4 | 191.8 | 159.0 | 178.0 | 211.7 | 209.2 | 2,440.9 |

| Source: Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanologia, Meteorologia, e Hidrologia[13] | |||||||||||||

Volcanic activity

Four stratovolcanoes are visible from the city, two of them active. The nearest and most active is Pacaya, which at times erupts a considerable amount of ash.[14] These volcanoes lie to the south of the Valle de la Ermita, providing a natural barrier between Guatemala City and the Pacific lowlands that define the southern regions of Guatemala. Agua, Fuego, Pacaya, and Acatenango comprise a line of 33 stratovolcanoes that stretches across the breadth of Guatemala, from the Salvadorian border to the Mexican border.

Earthquakes

Lying on the Ring of Fire, the Guatemalan highlands and the Valle de la Ermita are frequently shaken by large earthquakes. The last large tremor to hit the Guatemala City region occurred in the 1976, on the Motagua Fault, a left-lateral strike-slip fault that forms the boundary between the Caribbean Plate and the North American Plate. The 1976 event registered 7.5 on the moment magnitude scale. Smaller, less severe tremors are frequently felt in Guatemala City and environs.

Mudslides

Torrential downpours, similar to the more famous monsoons, occur frequently in the Valle de la Ermita during the rainy season, leading to flash floods that sometimes inundate the city. Due to these heavy rainfalls, some of the slums perched on the steep edges of the canyons that criss-cross the Valle de la Ermita are washed away and buried under mudslides, as in October 2005.[15] Tropical waves, tropical storms and hurricanes sometimes strike the Guatemalan highlands, which also bring torrential rains to the Guatemala City region and trigger these deadly mudslides.

Piping pseudokarst

In February 2007, a very large, deep circular hole with vertical walls opened in northeastern Guatemala City (14°39′1.40″N 90°29′25″W), killing five people. This sinkhole, which is classified by geologists as either a "piping feature" or "piping pseudokarst", was 100 metres (330 ft) deep, and apparently was created by fluid from a sewer eroding the loose volcanic ash, limestone, and other pyroclastic deposits that underlie Guatemala City.[16][17] As a result, one thousand people were evacuated from the area.[18] This piping feature has since been mitigated by City Hall by providing proper maintenance to the sewerage collection system,[19] and plans to develop the site have been proposed. However, critics believe municipal authorities have neglected needed maintenance on the city's aging sewerage system, and have speculated that more dangerous piping features are likely to develop unless action is taken.[20]

3 years later the 2010 Guatemala City sinkhole arose.

Demographics

It is estimated that the population of Guatemala City proper is about 3 million,[21][22] while its urban area is almost 5 million.[23] The growth of the city's population has been robust, abetted by the mass migration of Guatemalans from the rural hinterlands to the largest and most vibrant regional economy in Guatemala.[24] Among inhabitants of Guatemala City, those of Spanish and Mestizo descent are the most numerous.[24] Guatemala City also has sizable indigenous populations, divided among the 23 distinct Mayan groups present in Guatemala. The numerous Mayan languages are now spoken in certain quarters of Guatemala City, making the city a linguistically rich area. Foreigners and foreign immigrants comprise the final distinct group of Guatemala City inhabitants, representing a very small minority among the city's denizens.[24]

Due to mass migration from impoverished rural districts wracked with political instability, Guatemala City's population has exploded since the 1970s, severely straining the existing bureaucratic and physical infrastructure of the city. As a result, chronic traffic congestion, shortages of safe potable water in some areas of the city, and a sudden and prolonged surge in crime have become perennial problems. The infrastructure, although continuing to grow and improve in some areas,[25] is lagging in relation to the increasing population of rural migrants, who tend to be poorer.[26]

Communications

Guatemala City is headquarters to many communications and telecom companies, among them Tigo, Claro-Telgua, and Movistar-Telefónica. These companies also offer cable television, internet services and telephone access. Due to Guatemala City's large and concentrated consumer base in comparison to the rest of the country, these telecom and communications companies provide most of their services and offerings within the confines of the city. There are also seven local television channels, in addition to numerous international channels. The international channels range from children's programming, like Nickelodeon and the Disney Channel, to more adult offerings, such as E! and HBO. While international programming is dominated by entertainment from the United States, domestic programming is dominated by shows from Mexico. Due to its small and relatively income-restricted domestic market, Guatemala City produces very little in the way of its own programming outside of local news and sports.

Economy and finance

Guatemala City, as the capital, is home to Guatemala's central bank, from which Guatemala's monetary and fiscal policies are formulated and promulgated. Guatemala City is also headquarters to numerous regional private banks, among them CitiBank, Banco Agromercantil, Banco Promerica, Banco Industrial, Banco GyT Continental, Banco de Antigua, Banco Reformador, Banrural, Grupo Financiero de Occidente, BAC Credomatic, and Banco Internacional.

By far the richest and most powerful regional economy within Guatemala, Guatemala City is the largest market for goods and services, which provides the greatest number of investment opportunities for public and private investors in all of Guatemala. Financing for these investments is provided by the regional private banks, as well as through foreign direct investment mostly coming from the United States. Guatemala City's ample consumer base and service sector is represented by the large department store chains present in the city, among them Siman, Hiper Paiz & Paiz (Walmart), Price Smart, ClubCo, Cemaco, Sears, and Office Depot.

Agromercantil Bank

Agromercantil Bank

Places of interest by zones

Guatemala City is divided into 22 zones in accordance with the urban layout plan designed by Raúl Aguilar Batres. Each zone has its own streets and avenues, facilitating navigation within the city. Zones are numbered 1 through 25. However, numbers 20, 22 and 23 have not been designated to zones, thus these zones do not exist within the city proper.[9]

| Zone | Main places | Pictures | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zone 1 |

|

Guatemala National Palace of Culture | |

| Zone 2 |

|

Guatemala's relief map | |

| Zone 3 | |||

| Zone 4 |

|

||

| Zone 5 |

|

||

| Zone 6 | |||

| Zone 7 |

|

||

| Zone 9 |

|

Plazuela españa | |

| Zone 10 |

|

Zona Viva at night |

Sunrise on Diagonal 6 |

| Zone 11 |

|

||

| Zone 12 |

|

University of San Carlos Central Campus | |

| Zone 13 |

|

La Aurora International Airport |

Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología |

| Zone 14 |

|

||

| Zone 15 |

|

Latter Day Saints Guatemala City Temple | |

| Zone 16 |

|

Universidad Rafael Landívar |

Paseo Cayalá upscale new district |

Transportation

- Renovated and expanded, La Aurora International Airport lies to the south of the city center. La Aurora serves as Guatemala's principal air hub.

- Public transport is provided by buses and supplemented by a BRT system. The three main highways that bisect and serve Guatemala start in the city (CA9 Transoceanic Highway – Puerto San Jose to Puerto Santo Tomas de Castilla –, CA1 Panamerican Highway – from the Mexican border to Salvadorian border – and to Peten). Construction of freeways and underpasses by the municipal government, the implementation of reversible lanes during peak rush-hour traffic, as well as the establishment of the Department of Metropolitan Transit Police (PMT), has helped improve traffic flow in the city. Despite these municipal efforts, the Guatemala City metropolitan area still faces growing traffic congestion.

- A BRT (bus rapid transit) system called Transmetro, consisting of special-purpose lanes for high-capacity buses, began operating in 2007, and aimed to improve traffic flow in the city through the implementation of an efficient mass transit system. The system consists of five lines. It is expected to be expanded around 10 lines, with some over-capacity expected lines being considered for Light Metro or Heavy Metro.

Traditional buses are now required to discharge passengers at transfer stations at the city's edge to board the Transmetro. This is being implemented as new Transmetro lines become established. In conjunction with the new mass transit implementation in the city, there is also a prepaid bus card system called Transurbano that is being implemented in the metro area to limit cash handling for the transportation system. A new fleet of buses tailored for this system has been purchased from a Brazilian firm.

A light rail line known as Metro Riel is proposed.

Universities and schools

Guatemala City is home to ten universities, among them the oldest institution of higher education in Central America, the University of San Carlos of Guatemala. Founded in 1676, the Universidad de San Carlos is older than all North American universities except for Harvard University.

The other nine institutions of higher education to be found in Guatemala City include the Universidad Mariano Gálvez, the Universidad Panamericana, the Universidad Mesoamericana, the Universidad Rafael Landivar, the Universidad Francisco Marroquín, the Universidad del Valle, the Universidad del Istmo, Universidad Galileo, Universidad da Vinci, and the Universidad Rural. Whereas these nine named universities are private, the Universidad de San Carlos remains the only public institution of higher learning.

Sports

Guatemala City possesses several sportsgrounds and is home to many sports clubs. Football is the most popular sport, with CSD Municipal, Aurora F.C., and Comunicaciones being the main clubs.

The Estadio Doroteo Guamuch Flores, located in the Zone 5 of the city, is the largest stadium in the country, followed in capacity by the Estadio Cementos Progreso, Estadio del Ejército, and Estadio El Trébol. An important multi-functional hall is the Domo Polideportivo de la CDAG.

The city has hosted several promotional functions and some international sports events: in 1950 it hosted the VI Central American and Caribbean Games, and in 2000 the FIFA Futsal World Championship. On 4 July 2007 the International Olympic Committee gathered in Guatemala City and voted Sochi to become the host for the 2014 Winter Olympics and Paralympics.[30] In April 2010, it hosted the XIVth Pan-American Mountain Bike Championships.[31]

Guatemala City hosted the 2008 edition of the CONCACAF Futsal Championship, played at the Domo Polideportivo from 2 to 8 June 2008.[32]

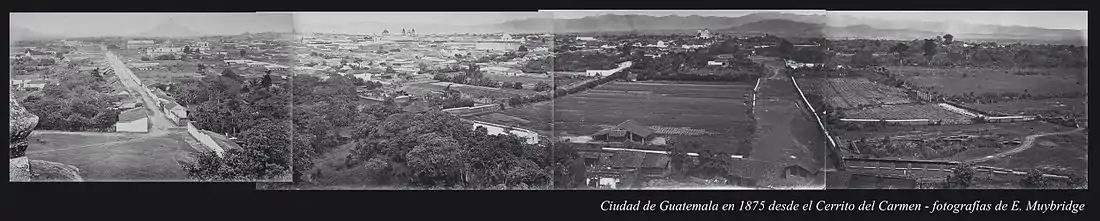

Panoramic views of Guatemala City

1875

2020

International relations

International organizations with headquarters in Guatemala City

Twin towns – sister cities

Guatemala City is twinned with:

| City | Jurisdiction | Country | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caracas | Capital District | 1969 | |

| San Salvador | San Salvador | 1979 | |

| Madrid | Madrid | 1983[33] | |

| Hollywood | Florida | 1987[34][35] | |

| Lima | Lima | 1987 | |

| Santiago de Chile | Metropolitan Santiago | 1991 | |

| Saltillo | Coahuila | 1993 | |

| La Habana | La Habana | 1997 | |

| Bogotá | Distrito Capital | 1997 | |

| San Pedro Sula | Cortés | 1999 | |

| Santa Cruz de Tenerife | Santa Cruz de Tenerife | 2002 | |

| San José | San José | 2005 | |

| Ciudad de Panamá | Panamá | 2005 | |

| Taipei | Northern Taiwan | 2007[36] | |

| Managua | Managua | 2008 | |

| Beijing | Beijing | 2009 | |

| Providence | Rhode Island | 2016[37] | |

Notable residents

- Raúl Aguilar Batres, engineer, creator of Guatemala City's system of avenue/street notation

- María Dolores Bedoya, Central American independence activist[38]

- Alejandro Giammattei, President of Guatemala

- Álvaro Arzú, President of Guatemala and six times mayor of Guatemala City

- Miguel Ángel Asturias, writer and diplomat, Nobel Prize Laureate

- Ricardo Arjona, singer-songwriter

- Manuel Colom Argueta, former mayor of Guatemala City and politician

- Toti Fernández, triathlete and ultramarathon runner

- Juan José Gutiérrez, CEO of Pollo Campero and on the board of directors of Corporación Multi Inversiones. He has been featured on the cover of Newsweek as Super CEO and named one of the Ten Big Thinkers for Big Business.[39]

- Ted Hendricks, Oakland Raiders NFL Hall of Fame Linebacker. 4-time Super Bowl Champion.

- Jorge de León, performance artist[40]

- Zipacná de León (1948–2002), painter

- Carlos Mérida, painter

- Jimmy Morales, Former President of Guatemala

- Gaby Moreno, singer-songwriter

- Carlos Peña, singer, winner of Latin American Idol 2007

- Luis Oliva, actor, singer and director

- Georgina Pontaza, actress and artistic director of the Teatro Abril and Teatro Fantasía

- Fernando Quevedo, theoretical physicist, professor of High Energy Physics at the University of Cambridge

- Rodolfo Robles, physician. He discovered onchocercosis "Robles' Disease".

- Fabiola Rodas, winner of The Third TV Azteca's Desafio de Estrellas, 2nd Place in The Last Generation of La Academia

- Gabriela Asturias Ruiz, neuroscientist

- Carlos Ruíz, football/soccer player

- Shery, singer-songwriter

- Jaime Viñals, mountaineer; he scaled seven highest peaks in the world

- Luis von Ahn, computer scientist, founder of Duolingo, CAPTCHA's creator and Researcher at Carnegie Mellon University

- Rodrigo Saravia, Guatemala national team footballer

- Sergio Custodio, professor and writer in logic and metaphysics

Notes and references

References

- "United Nations "Map"" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2001.

- https://www.censopoblacion.gt/mapas

- "Guatemala City, Guatemala Population". PopulationStat. 15 July 2020. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Article 231 of the Constitution of the Republic of Guatemala Archived 22 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- "Carlos Enrique Valladares Cerezo, "The case of Guatemala City, Guatemala"" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2004.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. (2019). United Provinces of Central America. In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 26, 2022. Archived 12 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- "Estos son los 4 lugares donde ha estado la capital de Guatemala". Aprende Guatemala.com (in Spanish). 2 October 2017. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- Wright, Lori E.; Valdés, Juan Antonio; Burton, James H.; Douglas Price, T.; Schwarcz, Henry P. (June 2010). "The children of Kaminaljuyu: Isotopic insight into diet and long distance interaction in Mesoamerica". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 29 (2): 155–178. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2010.01.002. ISSN 0278-4165.

- Municipalidad de Guatemala 2008.

- "City Layout in Guatemala City". Frommers. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- Morán Mérida 1994, p. 9.

- "Guatemala City, Guatemala Travel Weather Averages (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "Ministerio de comunicaciones Infraestructura y Vivienda". Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- "MTU-VP Pacaya Volcano, Guatemala". Geo.mtu.edu. 1 June 1995. Archived from the original on 4 February 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- Carlos, Juan (7 October 2005). "Mudslide in Guatemala kills dozens". San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- Waltham 2008, pp. 291–300.

- Halliday 2007, pp. 103–113.

- David L Miller (4 July 2009). "Massive Guatemala Sinkhole Kills 2 Teens". CBS News. Archived from the original on 25 February 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- Municipalidad de Guatemala 2014.

- Constantino Diaz-Duran (1 June 2010). "Sinkhole in Guatemala City Might Not Be the Last". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2010.

- "Guatemala: Estimaciones de la Población total por municipio. Período 2008-2020" [Guatemala: Estimates of the total population by municipality. 2008-2020 period.] (PDF). Organismo Judicial República de Guatemala (in Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- "Productividad y eficiencia: La Municipalidad incorpora tecnología para atender al vecino" [Productivity and efficiency: The municipality incorporates technology to service the neighbor]. Muniguate (in Spanish). 21 October 2018. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "CIA World Factbook, Guatemala". July 2011. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- INE 2013, p. 13.

- Morán Mérida 1994, p. 14.

- Morán Mérida 1994, pp. 14–17.

- "Mapa en Relieve de Guatemala". Funtec-Guatemala (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 February 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- Museo Ixchel 2008.

- "Jardin Botanico". Natureserve.org (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- "Topnews - Sport - Remscheid: Remscheider General-Anzeiger". Rga-online.de. Archived from the original on 5 June 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "XIVth Pan-American Mountain Bike Championships". guatepanamericanomtb2010.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2010.

- "Futsal Championship 2008 Recap". CONCACAF. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014.

- "Mapa Mundi de las ciudades hermanadas". Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- "Hollywood Adds Laayoune, Morocco as Sister City". City of Hollywood. 10 May 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- "Guatemala capital may be sister city". Sun Sentinel. 12 July 1987. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- "Taipei - International Sister Cities". Taipei City Council. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- "Guatemala City now sister city with Rhode Island's capital". AP NEWS. 12 October 2016. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- AGN. "María Dolores, la única mujer que participó en la independencia de Guatemala | Agencia Guatemalteca de Noticias" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- Contreras, Joseph (2005). "10 Big Thinkers for Big Business". Newsweek. p. 4. Archived from the original on 4 January 2009. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- Estey, Myles (15 August 2011). "Guatemala: art out of violence". Global Post. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

Bibliography

- Almengor, Oscar Guillermo (1994). "La Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción y los terremotos de 1917-18". Ciudad de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala: Centro de estudios urbanos y regionales-USAC.

- Assardo, Luis (2010). "Llueve ceniza y piedras del Volcán de Pacaya". El Periódico. Guatemala. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- Baily, John (1850). Central America; Describing Each of the States of Guatemala, Honduras, Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. London: Trelawney Saunders. p. 72. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- Barrios Vital, Jenny Ivette (2006). Restauración y revitalización del complejo arquitectónico de la Recolección (PDF) (Thesis) (in Spanish). Guatemala: University of San Carlos of Guatemala. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- Bascome Jones, J.; Scoullar, William T.; Soto Hall, Máximo (1915). El Libro azul de Guatemala (in Spanish). Searcy & Pfaff.

relato é historia sobre la vida de las personas más prominentes; historia condensada de la república; artículos especiales sobre el comercio, agricultura y riqueza mineral, basado sobre las estadísticas oficiales

- Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico: Vol. IV,2 (1999). "Atentados contra la libertad". Programa de Ciencia y Derechos Humanos, Asociación Americana del Avance de la Ciencia (in Spanish). Guatemala: memoria del silencio. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico: Vol. IV (1999). "Atentados contra sedes municipales". Programa de Ciencia y Derechos Humanos, Asociación Americana del Avance de la Ciencia (in Spanish). Guatemala: memoria del silencio. Archived from the original on 6 May 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- Conkling, Alfred R. (1884). Appleton's guide to Mexico, including a chapter on Guatemala, and a complete English-Spanish vocabulary. Nueva York: D. Appleton and Company. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- Dary Fuentes, Claudia (1994). "Una ciudad que empezaba a crecer". Revista Crónica, suplemento Revolución (in Spanish). Guatemala: Editorial Anahté.

- Diario de Navarra (2010). "El volcán Pacaya continúa activo y obliga a seguir con evacuaciones". Diario de Navarra (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 31 July 2014. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- El País (2010). "Socavón causado por la tormenta Agatha". El País (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012.

- El Periódico (31 January 2012). "Quema de embajada española". elPeriódico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- Figueroa, Luis (2011). "Bombazo en el Palacio Nacional". Luis Figueroa Blog (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- González Davison, Fernando (2008). La montaña infinita;Carrera, caudillo de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala: Artemis y Edinter. ISBN 978-84-89452-81-7.

- Guateantaño (17 October 2011). "Parques y plazas antiguas de Guatemala". Guatepalabras Blogspot. Guatemala. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015.

- Halliday, W.R. (2007). "Pseudokarst in the 21st century". Journal of Cave and Karst Studies. 69 (1): 103–113.

- INE (2013). "Caracterización Departamental, Guatemala 2012" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadística (in Spanish). Guatemala: Gobierno de Guatemala. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2014.

- Hernández de León, Federico (1959). "El capítulo de las efemérides". Diario La Hora (in Spanish). Guatemala.

- Hernández de León, Federico (1930). El libro de las efemérides (in Spanish). Vol. III. Guatemala: Tipografía Sánchez y de Guise.

- La Hora (2013). "Una crónica impactante en el aniversario de la quema de la Embajada de España tras 33 años de impunidad". Diario La Hora (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- La otra memoria histórica (5 December 2011). "Guatemala, viudas y huérfanos que dejó el comunismo". La otra memoria histórica (in Spanish). Guatemala. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Milla y Vidaurre, José (1980). Cuadros de Costumbres. Textos Modernos (in Spanish). Guatemala: Escolar Piedra Santa.

- Moncada Maya, José Omar (n.d.). "En torno a la destrucción de la ciudad de Guatemala, 1773. Una carta del ingeniero militar Antonio Marín". Ub.es (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 23 June 2003. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- Morán Mérida, Amanda (1994). "Movimientos de pobladores en la Ciudad de Guatemala (1944-1954)" (PDF). Boletín del CEUR-USAC (in Spanish). Guatemala: Centro de estudios urbanos y regionales-USAC (23). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- Mundo Chapín (2013). "La Aurora y el Hipódromo del Sur". Mundo Chapín. Guatemala. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- Municipalidad de Guatemala (2007). "Conmemoración de los doscientos treinta años de fundación de la Ciudad de Guatemala". Boletín de la Municipalidad de Guatemala. Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- Municipalidad de Guatemala (2008). "Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial, Ciudad de Guatemala" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 18 September 2009.

- Municipalidad de Guatemala (August 2008a). "Paso a desnivel de Tecún Umán". Segmento cultural de la Municipalidad de Guatemala (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 24 February 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- Municipalidad de Guatemala (2014). "Mi barrio querido, Ciudad de Guatemala" (in Spanish). Guatemala City. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- Museo Ixchel (2008). "Museo Ixchel". Museo Ixchel del traje indígena (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 February 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- Population data (2012). "Guatemala population". Population data. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- Prensa Libre (6 September 1980). "Avalancha terrorista en contra de la manifestación de mañana; poder público y transporte extraurbano blancos de ataque". Prensa Libre (in Spanish). Guatemala.

- Reilly, Michael (2 June 2010). "Don't Call the Guatemala Sinkhole a Sinkhole". Discovery News. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- Sharer, Robert J.; Traxler, Loa P. (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th (fully revised) ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4817-9. OCLC 57577446.

- Sydney Morning Herald (2010). "Hole that swallowed a three-story building". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014.

- Walker, Peter (2010). "Tropical Storm Agatha blows a hole in Guatemala City". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 19 March 2013.

- Waltham, T. (2008). "Sinkhole hazard case histories in karst terrains". Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology and Hydrogeology. 41 (3): 291–300. doi:10.1144/1470-9236/07-211. S2CID 128585380. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- Woodward, Ralph Lee Jr. (2002). "Rafael Carrera y la creación de la República de Guatemala, 1821–1871". Serie Monográfica (in Spanish). CIRMA y Plumsock Mesoamerican Studies (12). ISBN 0-910443-19-X. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- Woodward, Ralph Lee Jr. (1993). Rafael Carrera and the Emergence of the Republic of Guatemala, 1821-1871. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820343600. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

External links

Media related to Guatemala City at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Guatemala City at Wikimedia Commons Guatemala City travel guide from Wikivoyage

Guatemala City travel guide from Wikivoyage- Official Website of the Municipalidad de Guatemala Archived 11 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine