Sigismund Báthory

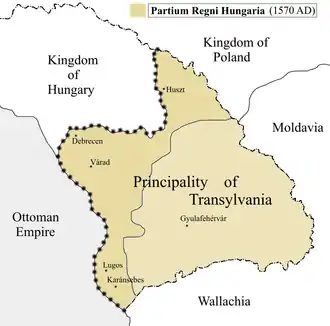

Sigismund Báthory (Hungarian: Báthory Zsigmond; 1573 – 27 March 1613) was Prince of Transylvania several times between 1586 and 1602, and Duke of Racibórz and Opole in Silesia in 1598. His father, Christopher Báthory, ruled Transylvania as voivode (or deputy) of the absent prince, Stephen Báthory. Sigismund was still a child when the Diet of Transylvania elected him voivode at his dying father's request in 1581. Initially, regency councils administered Transylvania on his behalf, but Stephen Báthory made János Ghyczy the sole regent in 1585. Sigismund adopted the title of prince after Stephen Báthory died.

| Sigismund Báthory | |

|---|---|

| Prince of Transylvania, Wallachia, and Moldavia, Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, Count of the Székelys and Lord of Parts of the Kingdom of Hungary | |

Portrait by Dominicus Custos | |

| Prince of Transylvania | |

| Reign | 1586–1598 |

| Predecessor | Stephen Báthory |

| Regent | János Ghyczy |

| Duke of Racibórz and Opole | |

| Reign | 1598 |

| Prince of Transylvania | |

| Reign | 1598–1599 |

| Successor | Andrew Báthory |

| Prince of Transylvania | |

| Reign | 1601–1602 |

| Predecessor | Michael the Brave (de facto) |

| Born | 1573 Várad, Principality of Transylvania (now Oradea, Romania) |

| Died | 27 March 1613 (aged 39–40) Libochovice, Kingdom of Bohemia |

| Burial | St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague, Kingdom of Bohemia |

| Spouse | Maria Christina of Habsburg |

| House | Báthory family |

| Father | Christopher Báthory |

| Mother | Elisabeth Bocskai |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

The Diet proclaimed Sigismund to be of age in 1588, but only after he agreed to expel the Jesuits. Pope Sixtus V excommunicated him, but the ban was lifted in 1590, and the Jesuits returned a year later. His blatant favoritism towards the Catholics made him unpopular among his Protestant subjects. He decided to join the Holy League against the Ottoman Empire. Since he could not convince the Diet to support his plan, he renounced the throne in July 1594, but the commanders of the army convinced him to revoke his abdication. At their proposal, he purged the noblemen who opposed the war against the Ottomans. He officially joined the Holy League and married Maria Christina of Habsburg, a niece of the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolph II. The marriage was never consummated.

Michael the Brave, Voivode of Wallachia, and Ștefan Răzvan, Voivode of Moldavia, acknowledged his suzerainty. Their united forces defeated an Ottoman army in the Battle of Giurgiu. The triumph was followed by a series of Ottoman victories, and Sigismund abdicated in favor of Rudolph II in early 1598, receiving the duchies of Racibórz and Opole as a compensation. His maternal uncle, Stephen Bocskai, persuaded him to return in late summer, but he could not make peace with the Ottoman Empire. He renounced Transylvania in favor of Andrew Báthory and settled in Poland in 1599. During the following years, Transylvania was regularly pillaged by unpaid mercenaries and Ottoman marauders. Sigismund returned at the head of a Polish army in 1601, but he could not strengthen his position. He again abdicated in favor of Rudolph and settled in Bohemia in June 1602. After he was accused of a conspiracy against the emperor, he spent fourteen months in jail in Prague in 1610 and 1611. He died at his Bohemian estate.

Early life

Sigismund was the son of Christopher Báthory and his second wife, Elisabeth Bocskai.[1] He was born in Várad (now Oradea in Romania) in 1573, according to the Transylvanian historian, István Szamosközy.[2] At the time of Sigismund's birth, his uncle, Stephen Báthory, was the voivode of Transylvania.[3] After being elected King of Poland in late 1575, Stephen Báthory adopted the title of Prince of Transylvania and made Sigismund's father voivode.[4] Stephen Báthory set up a separate chancellery in Kraków to supervise the administration of the principality.[5]

Sigismund's father and uncle were Roman Catholic, but his mother was Calvinist.[2] According to the Jesuit Antonio Possevino, Sigismund demonstrated his devotion to Catholicism already at the age of seven.[2] His mother mocked him for his piety, saying that he only wanted to secure his uncle's goodwill.[2] Sigismund was especially hostile towards the Anti-Trinitarians in his youth.[2] His mother died in early 1581.[2]

Reign

Voivode

Christopher Báthory fell seriously ill after his wife's death.[3] At his request, the Diet of Transylvania elected Sigismund voivode in Kolozsvár (present-day Cluj-Napoca in Romania) around 15 May 1581.[6][1] Since Sigismund was still a minor, his dying father tasked a council of twelve noblemen with the government.[3] Christopher Báthory's cousin, Dénes Csáky, and his brother-in-law, Stephen Bocskai, headed the council.[3] Christopher Báthory died on 27 May.[6]

The Ottoman Sultan, Murad III, confirmed Sigismund's election on 3 July 1581, reminding him of his obligation to pay a yearly tribute of 15,000 florins.[7] However, Pál Márkházy, a young nobleman who lived in Istanbul, offered to double the tribute and to pay an additional tax of 100,000 florins if he was made the ruler of Transylvania.[8] The Grand Vizier, Koca Sinan Pasha, supported Márkházy's claim.[8] Taking advantage of the situation, Murad demanded the same payments from Sigismund, but Stephen Báthory and the "Three Nations of Transylvania" resisted.[8] After receiving the customary tribute from Transylvania, the sultan again confirmed Sigismund's rule in November 1581.[8]

Stephen Báthory who took charge of Sigismund's education confirmed the position of his Jesuit tutors, János Leleszi and Gergely Vásárhelyi.[9] According to Szamosközy, Stephen Báthory also ordered Sigismund's companions to talk of foreign lands, wars, and hunting with him during their dinners together.[9] He reorganized the government on 3 May 1583, charging Sándor Kendi, Farkas Kovacsóczy, and László Sombori with the administration of Transylvania during Sigismund's minority.[9][10] The Diet suggested to Stephen Báthory that he dismiss them, but he only dissolved the council on 1 May 1585.[11] He replaced the three councillors with the devout Calvinist János Ghyczy, making him regent for Sigismund.[1][11]

Prince under guardianship

Sigismund adopted the title of Prince of Transylvania after Stephen Báthory died on 13 December 1586.[11][12] He was still a minor, and Ghyczy continued to rule as regent.[1][13] Sigismund was one of the candidates to the throne of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[14] His advisors knew that he had little chance to win, but they wanted to demonstrate that the Báthorys had a valid claim to rule the Commonwealth.[15] Kovacsóczy officially announced Sigismund's application at the Sejm (or general assembly) on 14 August 1587.[16] Five days later, the assembly elected Sigismund III Vasa king.[17] During the ensuing war of succession, Transylvanian troops supported Sigismund III against Maximilian of Habsburg, who had also laid claim to Poland and Lithuania.[18]

Sigismund's cousins, Balthasar and Stephen Báthory, returned from Poland to Transylvania.[13][19] Balthasar wanted to take charge of the government, making his court at Fogaras (present-day Făgăraș in Romania) the center of those who opposed Ghyczy's rule.[13][19] Kovacsóczy, the chancellor of Transylvania, remained neutral in the conflict.[13]

In October 1588 the Diet proposed to declare the sixteen-year-old Sigismund of age if he banished the Jesuits from Transylvania.[13] He did not accept the offer, mainly because he did not want to expel his confessor, Alfonso Carillo.[13] The Diet was dissolved, but Sigismund's cousins convinced him not to resist the Diet, which was dominated by Protestant delegates.[13] The Diet was again summoned in late 1588; on 8 December it ordered the expulsion of the Jesuits and declared Sigismund to be of age.[13][20]

Internal conflicts

Sigismund took the customary oath of the Transylvanian monarchs on 23 December 1588.[20] Pope Sixtus V excommunicated him for the expulsion of the Jesuits.[21] Sigismund's cousin, Cardinal Andrew Báthory, urged the pope to lift the ban, saying that the prince's Protestant advisors had forced him to throw out the priests.[21] The pope authorized Sigismund to employ a confessor in May 1589, and the excommunication was revoked on Easter 1590.[22]

Sigismund made several attempts to strengthen the position of the Roman Catholic Church, especially by appointing Catholics to the highest positions of state administration.[23] Carillo and other Jesuit priests returned to Sigismund's court in disguise in early 1591.[20][24] Sigismund met Andrew and Balthasar Báthory in August to seek their support for the legalization of the Jesuits' presence, but they refused to stand by the priests at the Diet.[24]

Sigismund dispatched his favorite, István Jósika, to Tuscany to start negotiations regarding his marriage to Eleonora Orsini (a niece of Ferdinando I de' Medici), although his cousins had sharply opposed Jósika's appointment.[25] He also invited Italian artists and artisans to his court, making them his advisors or butlers.[26] Szamosközy described them as "the trashiest representatives of the noblest nation".[26] The delegates of the "Three Nations" criticized Sigismund for his prodigal way of life at the Diet in Gyulafehérvár in November.[27] To reduce his authority, the Diet prescribed that Sigismund should only make decisions in the royal council.[28][29] Sigismund deprived his cousins of the allowances that the royal treasury had paid to them.[27]

Gossip about conspiracies spread during the following months.[27] Sándor Kendi accused Sigismund's former tutor, János Gálffy, of deliberately stirring up debates between the prince and his cousins.[27] Other courtiers claimed that Balthasar Báthory was planning to dethrone Sigismund.[27] A Jesuit priest was informed at Vienna that Gálffy and his allies wanted to murder the prince and his cousins.[30] In late 1591 Sigismund stated that he was willing to renounce in favor of Balthasar if the members of the royal council favored his cousin.[31] His offer was refused, but during the debate Kendi referred to Sigismund and Balthasar as the "two monsters and greatest disasters of the Transylvanian realm".[31] Pope Clement VIII's legate, Attilio Amalteo, mediated a reconciliation between Sigismund and his cousins in the summer of 1592.[32] The pope also urged Sigismund to marry a Catholic princess from the House of Lorraine.[33]

At the demand of the sultan, Transylvania troops assisted Aaron the Tyrant, Voivode of Moldavia.[32] The sultan also ordered Sigismund to pay double the amount of the yearly tribute.[32] Balthasar Báthory murdered Sigismund's secretary, Pál Gyulai, on 10 December 1592.[32] He also persuaded Sigismund to order the execution of Gálffy on 8 March 1593.[32] That summer, Sigismund went to Kraków in disguise to start negotiations regarding his marriage with Anna, the sister of Sigismund III of Poland.[34] The Holy See had proposed the marriage, which could have enabled Sigismund to rule Poland during the absence of the king, who was also King of Sweden, but the plan came to nothing.[34]

Murad III declared war against the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolph in August.[32] The sultan ordered Sigismund to send reinforcements to support the Ottoman army in Royal Hungary.[32] According to diplomatic sources, the grand vizier was planning to occupy Transylvania.[35] At the proposal of Jan Zamoyski, Chancellor of Poland, Sigismund sent envoys to Elizabeth I of England, asking her to intervene on his behalf at the Sublime Porte.[35] She ordered her ambassador at Istanbul, Edward Barton, to support Sigismund.[35]

Pope Clement VIII wanted to persuade Sigismund to join the Holy League that the pope had organized against the Ottoman Empire.[36] After Rudolph's troops defeated the Ottomans in a series of battles in the autumn of 1593, Sigismund decided to join the Holy League, provided that Rudolph acknowledged the independence of Transylvania from the Hungarian Crown.[36][28][37] However, the delegates of the Three Nations refused to declare war against the Ottoman Empire at three consecutive Diets between May and July.[28][38] Sigismund abdicated, tasking Balthasar Báthory with the government in late July.[39] Balthasar wanted to seize the throne, but Kovacsóczy, Kendi, and the other leading officials decided to set up an aristocratic council to administer Transylvania.[40]

The commanders of the army (including Stephen Bocskai), and Friar Carillo jointly convinced Sigismund to return on 8 August.[28][39][40] They also persuaded him to order the arrest of Kovacsóczy, Kendi, Balthasar Báthory, and twelve other noblemen who had opposed the war against the Ottomans on 28 August, accusing them of plotting.[40][41] Sándor and Gábor Kendi were beheaded along with two other members of the royal council; Balthasar Báthory, Kovacsóczy, and Ferenc Kendi were strangled in prison.[28][42] All but one murdered noblemen were Protestants, mostly Unitarians.[43] Many of their relatives converted to Catholicism to prevent the confiscation of their estates.[43]

Holy League

Sigismund decided to join the Holy League together with Aaron the Tyrant, voivode of Moldavia, and Michael the Brave, voivode of Wallachia, on 5 October 1594.[39] The two voivodes had started direct negotiations with the Holy See, but Sigismund, who claimed suzerainty over them, prevented them from conducting further direct negotiations.[44] Sigismund's envoy, Stephen Bocskai, signed the document that confirmed the membership of Transylvania in the Holy League in Prague on 28 January 1595.[28] According to the treaty, Rudolph II recognized Sigismund's hereditary right to rule Transylvania and Partium and to use the title of prince, but he also stipulated that the principality was to be re-united with the Hungarian Crown if Sigismund's family died out.[45] The Diet of Transylvania confirmed the treaty on 16 April.[45] The Diet also prohibited religious innovations, which gave rise to the persecution of Szekler Sabbatarians in Udvarhelyszék.[46]

The Wallachian boyars and prelates recognized Sigismund's suzerainty over Wallachia on behalf of Michael the Brave in Gyulafehérvár on 20 May 1595.[44][47] According to the treaty, Michael was forbidden to enter into an alliance with foreign powers without Sigismund's approval.[44] The voivode's right to sentence his boyars to death was also limited.[44] The Diet of Transylvanian was authorized to impose taxes in Wallachia with a council of twelve boyars.[44][47] After Aaron the Tyrant refused to sign a similar treaty, Sigismund invaded Moldavia and captured him in Iași.[47][45] He made Ștefan Răzvan the new voivode on 3 June, forcing him to swear fealty to him.[47][45] Thereafter, Sigismund styled himself "By the Grace of God, Prince of Transylvania, Wallachia and Moldavia, Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, Count of the Székelys and Lord of Parts of the Kingdom of Hungary".[48][49]

Sigismund married Maria Christina of Habsburg, a niece of Rudolph II, on 6 August.[45] However, the marriage was never consummated.[50] Sigismund accused Margit Majláth (who was the mother of his executed cousin, Balthasar Báthory) of witchcraft, causing his impotence.[51] Historian László Nagy notes that Sigismund's contemporaries made no reference to his relationship with women, showing that Sigismund was homosexual.[52]

György Borbély, Ban of Karánsebes, captured Lippa (now Lipova in Romania) and other Ottoman fortresses along the Maros River before the end of August.[45][53] Koca Sinan Pasha broke into Wallachia, forcing Michael the Brave to retreat towards Transylvania.[54] Michael routed the invaders in the Battle of Călugăreni, but he could not prevent them from seizing Târgoviște and Bucharest.[54] He withdrew to Stoenești to await the arrival of the Transylvanian and Moldavian troops.[54]

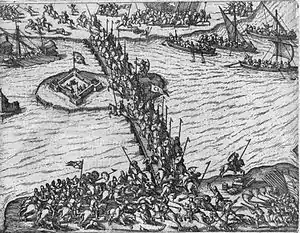

Since the Ottoman army outnumbered the forces at Sigismund's disposal, he proposed the Székely commoners (who had been reduced to serfdom in the 1560s) to restore their freedom if they joined his campaign against the Ottomans.[55][53] The Székelys accepted his offer, enabling Sigismund to launch a counter-invasion in Wallachia in early October.[53][45] The united forces of Transylvania, Wallachia, and Moldavia defeated the retreating Ottoman army in the Battle of Giurgiu on 25 October.[56] Although the victory was not decisive, the battle enabled the two voivodes to maintain their alliance with the Holy League.[57]

Ignoring the Székely warriors' preeminent role during the war, the Diet of Transylvania refused to restore their freedom on 15 December.[53][58] Sigismund left for Prague to start negotiations with Rudolph II in early January 1596, tasking his wife and Stephen Bocskai with the government.[58] The Székelys tried to secure their freedom, but Bocskai repressed their movement with extraordinary cruelty during the "Bloody Carnival" in early 1596.[53][58]

Rudolph II promised Sigismund to send reinforcements and money to continue the war against the Ottomans.[58][59] Sigismund returned to Transylvania on 4 March.[58][59] He laid siege to Temesvár (now Timișoara in Romania), but he lifted the siege when an Ottoman army of 20,000 strong approached the fortress.[59] The Ottoman Sultan Mehmed III invaded Royal Hungary in summer.[60] Sigismund joined his forces with the royal army, which was under the command of Maximilian of Habsburg.[60] However, the Ottomans routed their united army in the Battle of Mezőkeresztes between 23 and 26 October.[53]

Sigismund again went to Prague to meet Rudolph II and offered to abdicate in January 1597.[60] After he returned to Transylvania, he restored the Roman Catholic bishopric in Gyulafehérvár.[60] He sent envoys to Italy to demand the supreme command of a new Christian army, but his delegates at Istanbul started negotiations regarding a reconciliation with the sultan.[61]

Abdications and returns

The failure of his marriage and the defeats of the Holy League diminished Sigismund's self-confidence.[62] He sent his envoys to Rudolph II and again offered to abdicate in September 1597.[61][60] An agreement regarding his abdication was signed on 23 December 1597.[63] Rudolph II granted Sigismund the Silesian duchies of Racibórz and Opole and a yearly subsidy of 50,000 thalers.[61] The agreement was kept secret for months.[63]

The Diet of Transylvania acknowledged Sigismund's abdication on 23 March 1598.[63] Maria Christierna took charge of the government until the arrival of Maximilian of Habsburg, whom Rudolph II had appointed to administer Transylvania.[61] Sigismund went to Silesia, but he did not like his new duchies.[64][62] Bocskai, who had been dismissed after Sigismund's abdication, urged him to return.[53]

Sigismund came to Kolozsvár on 21 August.[64] On the following day, Bocskai convoked the Diet to his military camp at Szászsebes (now Sebeș in Romania), and the delegates proclaimed Sigismund prince.[64] Most Transylvanians accepted the decision, but György Király, the deputy captain of Várad, remained loyal to Rudolph II.[65] In September an Ottoman army invaded the principality, capturing the fortresses along the Maros.[66] Sigismund sent his envoys to the commander of the army, Mehmed, convincing him to attack Várad instead of breaking into Transylvania proper.[65]

All of Sigismund's attempts to make peace with the sultan failed.[53] He sent his envoys to Prague to negotiate with Rudolph II,[66] while his confessor, Carillo, started negotiations with Jan Zamoyski in Poland.[53] At Sigismund's invitation, his cousin, Andrew Báthory, returned from Poland.[66] Sigismund abdicated at the Diet in Medgyes (now Mediaș in Romania) on 21 March 1599.[66] Eight days later, the Diet proclaimed Andrew Báthory prince, hoping that Andrew could make peace with the Ottomans with the assistance of Poland.[66][67] Sigismund left Transylvania for Poland in June.[65][68] His marriage with Maria Christierna was declared invalid in Rome in August.[69]

Andrew Báthory lost his throne and his life fighting against Michael the Brave and his Székely allies in autumn.[70] Michael the Brave administered Transylvania as Rudolph II's governor, but his rule was unpopular among the noblemen, especially because of the pillaging raids made by his unpaid soldiers.[70][71] As early as 9 February 1600 Sigismund announced that he was ready to return to Transylvania.[72] Moses Székely, a commander-in-chief during Michael the Brave's campaign against Moldavia in May, deserted Michael and came to Poland to meet Sigismund.[72]

The elected leader of the Transylvanian noblemen, István Csáky, sought assistance from Rudolph II's military commander, Giorgio Basta, against Michael.[70][73] Basta invaded Transylvania and expelled Michael the Brave in September.[70][73] Basta's unpaid soldiers regularly pillaged the principality, while Ottoman and Tatar marauders made frequent incursions across the frontiers.[70] Sigismund returned to Transylvania across Moldavia at the head of a Polish army on 24 March 1601.[70][74] The Diet proclaimed him prince in Kolozsvár on 3 April.[74] Basta and Michael the Brave invaded Transylvania in summer.[70] They routed Sigismund's army in the Battle of Goroszló on 3 August 1601.[70] After the battle, Sigismund fled to Moldavia, but he returned on 6 September.[75]

The sultan's envoy confirmed Sigismund's position as Prince of Transylvania in Brassó (now Brașov in Romania) on 2 October.[75] At the head of an army which also included Ottoman and Tatar soldiers, Sigismund expanded his rule over most regions of the principality,[76] but he could not capture Kolozsvár in late November.[75] He started new negotiations with Basta over his abdication in March 1602, because he did not trust his own supporters.[75][76][77] He referred to them as "intoxicated and brutish sons of a bitch" and asked István Csáky to help him to leave their camp on 2 July.[77] He left Transylvania for the last time on 26 July 1602.[78]

Last years

Basta's soldiers accompanied Sigismund to Tokaj.[77] Before long, he went to Prague to beg for Rudolph II's mercy.[77] He received the incolatus (or the right to own lands in Bohemia) in 1604.[77] After the Diet of Transylvania proclaimed Stephen Bocskai prince in February 1605, Rudolph tried to persuade Sigismund to return to Transylvania, but he did not accept the offer.[79] The ambassadors of Venice and Spain and the emperor again tried to convince him to lay claim to Transylvania in July 1606, but Sigismund refused, saying that he had no information about the affairs of his former principality.[77] In December he again met Rudolph in Prague, but still resisted the emperor's offer.[77]

Sigismund received the domain of Libochovice in Bohemia.[77] After one of his employees accused him of plotting against the emperor, Sigismund was imprisoned for fourteen months in the jails of Prague Castle in 1610.[62][80] Sigismund died of a stroke in Libochovice on 27 March 1613.[62] He was buried in a crypt in the St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague.[62]

References

- Szabó 2012, p. 184.

- Nagy 1984, p. 97.

- Nagy 1984, p. 99.

- Barta 1994, pp. 261, 264.

- Felezeu 2009, p. 27.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 406.

- Felezeu 2009, pp. 54–55.

- Felezeu 2009, p. 55.

- Nagy 1984, p. 100.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 407.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 408.

- Szegedi 2009, p. 101.

- Barta 1994, p. 293.

- Horn 2002, p. 109.

- Horn 2002, pp. 105–106.

- Horn 2002, pp. 109–110.

- Horn 2002, p. 110.

- Horn 2002, pp. 117–119.

- Nagy 1984, p. 101.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 410.

- Horn 2002, p. 133.

- Horn 2002, p. 134.

- Keul 2009, p. 127.

- Horn 2002, p. 162.

- Horn 2002, pp. 161, 163.

- Nagy 1984, p. 103.

- Horn 2002, p. 164.

- Barta 1994, p. 294.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 411.

- Horn 2002, p. 166.

- Horn 2002, p. 167.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 412.

- Horn 2002, p. 168.

- Horn 2002, p. 177.

- Horn 2002, p. 178.

- Horn 2002, p. 180.

- Granasztói 1981, pp. 412–413.

- Granasztói 1981, pp. 413–414.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 414.

- Horn 2002, p. 183.

- Nagy 1984, p. 108.

- Nagy 1984, pp. 108–109.

- Keul 2009, p. 139.

- Pop 2009, p. 78.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 415.

- Keul 2009, p. 140.

- Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 144.

- Szekeres 2007, p. 118.

- Pop 2009, p. 79.

- Nagy 1984, p. 126.

- Sz. Kristóf 2013, p. 348.

- Nagy 1984, p. 131.

- Barta 1994, p. 295.

- Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 145.

- Nagy 1984, p. 117.

- Nagy 1984, p. 119.

- Nagy 1984, p. 122.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 416.

- Nagy 1984, p. 123.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 417.

- Nagy 1984, p. 135.

- Szabó 2012, p. 186.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 418.

- Nagy 1984, p. 136.

- Nagy 1984, p. 137.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 419.

- Barta 1994, pp. 295–296.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 420.

- Horn 2002, p. 215.

- Barta 1994, p. 296.

- Pop 2009, p. 296.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 421.

- Pop 2009, pp. 296–297.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 422.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 423.

- Barta 1994, p. 297.

- Nagy 1984, p. 141.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 424.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 428.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 439.

Sources

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 513–514.

- Barta, Gábor (1994). "The Emergence of the Principality and its First Crises (1526–1606)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.). History of Transylvania. Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 247–300. ISBN 963-05-6703-2.

- Bolovan, Ioan; Constantiniu, Florin; Michelson, Paul E.; Pop, Ioan Aurel; Popa, Cristian; Popa, Marcel; Scurtu, Ioan; Treptow, Kurt W.; Vultur, Marcela; Watts, Larry L. (1997). A History of Romania. The Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 973-98091-0-3.

- Felezeu, Călin (2009). "The International Political Background (1541–1699); The Legal Status of the Principality of Transylvania in Its Relations with the Ottoman Porte". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas; Magyari, András (eds.). The History of Transylvania, Vo. II (From 1541 to 1711). Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies. pp. 15–73. ISBN 978-973-7784-04-9.

- Granasztói, György (1981). "A három részre szakadt ország és a török kiűzése (1557–1605)". In Benda, Kálmán; Péter, Katalin (eds.). Magyarország történeti kronológiája, II: 1526–1848 [Historical Chronology of Hungary, Volume I: 1526–1848] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 390–430. ISBN 963-05-2662-X.

- Horn, Ildikó (2002). Báthory András [Andrew Báthory] (in Hungarian). Új Mandátum. ISBN 963-9336-51-3.

- Keul, István (2009). Early Modern Religious Communities in East-Central Europe: Ethnic Diversity, Denominational Plurality, and Corporative Politics in the Principality of Transylvania (1526–1691). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17652-2.

- Nagy, László (1984). A rossz hírű Báthoryak [The Báthorys of Bad Fame] (in Hungarian). Kossuth. ISBN 963-09-2308-4.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel (2009). "Michael the Brave and Transylvania". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas; Magyari, András (eds.). The History of Transylvania, Vo. II (From 1541 to 1711). Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies. pp. 75–96. ISBN 978-973-7784-04-9.

- Szabó, Péter Károly (2012). "Báthory Zsigmond". In Gujdár, Noémi; Szatmáry, Nóra (eds.). Magyar királyok nagykönyve: Uralkodóink, kormányzóink és az erdélyi fejedelmek életének és tetteinek képes története [Encyclopedia of the Kings of Hungary: An Illustrated History of the Life and Deeds of Our Monarchs, Regents and the Princes of Transylvania] (in Hungarian). Reader's Digest. pp. 184–187. ISBN 978-963-289-214-6.

- Szegedi, Edit (2009). "The Birth and Evolution of the Principality of Transylvania (1541–1690)". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas; Magyari, András (eds.). The History of Transylvania, Vo. II (From 1541 to 1711). Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies. pp. 99–111. ISBN 978-973-7784-04-9.

- Szekeres, Lukács Sándor (2007). Székely Mózes: Erdély székely fejedelme [Moses Székely: The Székely Prince of Transylvania] (in Hungarian).

- Sz. Kristóf, Ildikó (2013). "Witch-Hunting in Early Modern Hungary". In Levack, Brian P. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America. Oxford University Press. pp. 334–354. ISBN 978-0-19-957816-0.