9-1-1

9-1-1,[2][3] usually written 911, is an emergency telephone number for the United States, Canada, Mexico, Panama, Palau, Argentina, Philippines, Jordan, as well as the North American Numbering Plan (NANP), one of eight N11 codes. Like other emergency numbers around the world, this number is intended for use in emergency circumstances only. Using it for any other purpose (such as making false or prank calls) is a crime in most jurisdictions.

In over 98% of locations in Argentina, Panama, Belize, Anguilla, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Jordan, Ethiopia, Liberia, Saudi Arabia, Philippines, Uruguay, United States, Palau, Mexico, Tonga and Canada, dialing "9-1-1" from any telephone will link the caller to an emergency dispatch office—called a Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP) by the telecommunications industry—which can send emergency responders to the caller's location in an emergency. In approximately 96 percent of the United States, the enhanced 9-1-1 system automatically pairs caller numbers with a physical address.[2]

In the Philippines, the 9-1-1 emergency hotline has been available to the public since August 1, 2016, starting in Davao City. It is the first of its kind in Asia-Pacific region.[4] It replaces the previous emergency number 117 used outside Davao City.

As of 2017, a 9-1-1 system is in use in Mexico, where implementation in different states and municipalities is being conducted. Venezuela also has a 911 emergency services called VEN911. It has been in operation for approximately 10 years.

History

The first known use of a national emergency telephone number began in the United Kingdom in 1937–1938 using the number 999, which continues to this day.[5] In the United States, the first 911 call was made in Haleyville, Alabama in 1968 by Alabama Speaker of the House Rankin Fite and answered by U.S. Rep. Tom Bevill.[6][7] In Canada, 911 service was adopted in 1972, and the first 911 call occurred after 1974 roll-out in London, Ontario.[8]

In the United States, the push for the development of a nationwide American emergency telephone number came in 1957 when the National Association of Fire Chiefs recommended that a single number be used for reporting fires.[9] The first city in North America to use a central emergency number was the Canadian city of Winnipeg, Manitoba in 1959, which instituted the change at the urging of Stephen Juba, mayor of Winnipeg at the time.[10] Winnipeg initially used 999 as the emergency number,[11] but switched numbers when 9-1-1 was proposed by the United States.

In 1964, an attack on a woman in New York City, Kitty Genovese, helped to greatly increase the urgency to create a central emergency number. The New York Times falsely reported that nobody had called the police in response to Genovese's cries for help. Some experts theorized that one source of reluctance to call police was due to the complexity of doing so; any calls to the police would go to a local precinct, and any response might depend on which individual sergeant or other ranking personnel might handle the call.[12][13][14][15][16]

In 1967, the President's Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice recommended the creation of a single number that could be used nationwide for reporting emergencies. The Federal Communications Commission then met with AT&T in November 1967 in order to choose the number.[9]

In 1968, the number was agreed upon. AT&T chose the number 9-1-1, which was simple, easy to remember, dialed easily (which, with the rotary dial phones in place at the time, 999 would not), and because of the middle 1, which indicating a special number (see also 4-1-1 and 6-1-1), worked well with the phone systems at the time.[9] At the time, this announcement only affected the Bell System telephone companies; independent phone companies were not included in the emergency telephone plan. Alabama Telephone Company decided to implement it ahead of AT&T, choosing Haleyville, Alabama, as the location.[17]

AT&T made its first implementation in Huntington, Indiana on March 1, 1968. However, the rollout of 9-1-1 service took many years. For example, although the City of Chicago, Illinois, had access to 9-1-1 service as early as 1976, the Illinois Commerce Commission did not authorize telephone service provider Illinois Bell to offer 9-1-1 to the Chicago suburbs until 1981.[18] Implementation was not immediate even then; by 1984, only eight Chicago suburbs in Cook County had 9-1-1 service.[19] As late as 1989, at least 28 Chicago suburbs still lacked 9-1-1 service; some of those towns had previously elected to decline 9-1-1 service due to costs and—according to emergency response personnel—failure to recognize the benefits of the 9-1-1 system.[20]

Regarding national U.S. coverage, by 1979, 26% of the U.S. population could dial the number. This increased to 50% by 1987 and 93% by 2000.[9] As of March 2022, 98.9% of the U.S. population has access.[21]

Conversion to 9-1-1 in Canada began in 1972, and as of 2018 virtually all areas (except for some rural areas, such as Nunavut[22]) are using 9-1-1. As of 2008, each year Canadians make twelve million calls to 9-1-1.[23] On November 4, 2019, the Northwest Territories launched the 9-1-1 service across the territory with the ability to receive service in the territory's 11 Official languages.[24]

On September 15, 2010, AT&T announced that the State of Tennessee had approved a service to support a Text-to-9-1-1 trial statewide, where AT&T would be able to allow its users to send text messages to 9-1-1 PSAPs.[25]

Most British Overseas Territories in the Caribbean use the North American Numbering Plan; Anguilla, Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, and the Cayman Islands use 9-1-1.

Mexico switched its emergency phone number from 066 to 9-1-1 in 2016 and 2017.[26][27]

Enhanced 9-1-1

Enhanced 9-1-1 (E-911 or E911) automatically gives the dispatcher the caller's location, if available.[2] Enhanced 9-1-1 is available in most areas, including approximately 96 percent of the U.S.

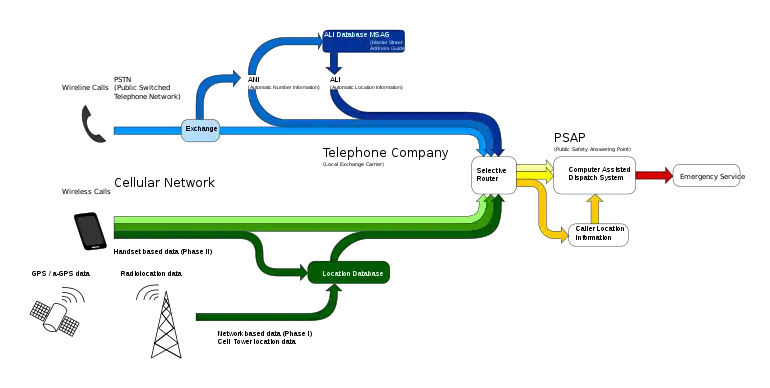

In all North American jurisdictions, special legislation permits emergency operators to obtain a 9-1-1 caller's telephone number and location information.[28] This information is gathered by mapping the calling phone number to an address in a database. This database function is known as Automatic Location Identification (ALI).[29] The database is generally maintained by the local telephone company, under a contract with the PSAP. Each telephone company has its standards for the formatting of the database. Most ALI databases have a companion database known as the MSAG, Master Street Address Guide. The MSAG describes address elements including the exact spellings of street names, and street number ranges.

To locate a mobile telephone geographically, there are two general approaches: some form of radiolocation from the cellular network, or to use a Global Positioning System receiver built into the phone itself. Both approaches are described by the radio resource location services protocol (LCS protocol). Depending on the mobile phone hardware, one of two types of location information can be provided to the operator. The first is Wireless Phase One (WPH1), which is the tower location and the direction the call came from, and the second is Wireless Phase Two (WPH2), which provides an estimated GPS location.

As Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) technology matured, service providers began to interconnect VoIP with the public switched telephone network and marketed the VoIP service as a cheap replacement phone service. However, E-911 regulations and legal penalties have severely hampered the more widespread adoption of VoIP: VoIP is much more flexible than landline phone service, and there is no easy way to verify the physical location of a caller on a nomadic VoIP network at any given time (especially in the case of wireless networks), and so many providers offered services which specifically excluded 9-1-1 service to avoid the severe E-911 non-compliance penalties. VoIP services tried to improvise, such as routing 9-1-1 calls to the administrative phone number of the Public Safety Answering Point, adding on software to track phone locations, etc.

In response to the E-911 challenges inherent to IP phone systems, specialized technology has been developed to locate callers in the event of an emergency. Some of these new technologies allow the caller to be located down to the specific office on a particular floor of a building. These solutions support a wide range of organizations with IP telephony networks. The solutions are available for service providers offering hosted IP PBX and residential VoIP services. This increasingly important segment in IP phone technology includes E-911 call routing services and automated phone tracking appliances. Many of these solutions have been established according to FCC, CRTC, and NENA i2 standards, to help enterprises and service providers reduce liability concerns and meet E-911 regulations.[30]

Computer-aided dispatch

9-1-1 dispatchers use computer-aided dispatch (CAD) to record a log of EMS, police and fire services. It can either be used to send messages to the dispatched via a mobile data terminal (MDT) and/or used to store and retrieve data (i.e. radio logs, field interviews, client information, schedules, etc.). A dispatcher may announce the call details to field units over a two-way radio. Some systems communicate using a two-way radio system's selective calling features.

CAD systems may send text messages with call-for-service details to alphanumeric pagers or wireless telephony text services like SMS.

Funding

In the United States and Canada, 9-1-1 is typically funded via monthly fees on telephone customers. Telephone companies, including wireless carriers, may be entitled to apply for and receive reimbursements for costs of their compliance with laws requiring that their networks be compatible with 9-1-1. Fees depend on locality and may range from around $.25 to $3.00 per month, per line.[31] The average wireless 9-1-1 fee is around $.72.

Monthly fees usually do not vary based on the customer's usage of the network, though some states do cap the number of lines subject to the fee for large multi-line businesses.

These fees defray the cost of providing the technical means for connecting callers to a 9-1-1 dispatch center; emergency services themselves are funded separately.

Problems

Inactive telephones

Some U.S. states required that all landline telephones connected to the network be able to reach 9-1-1, even if normal service has been disconnected (as for nonpayment).[32] In the U.S., carriers are required to connect 9-1-1 calls from inactive mobile phones.[33] Similar rules apply in Canada.[34] However, dispatchers may not receive Phase II information for inactive lines, and may not be able to call back if an emergency call is disconnected.[35]

Cell phones

About 70 percent of 9-1-1 calls came from cell phones in 2014,[36] and finding out where the calls came from required triangulation. A USA Today study showed that where information was compiled on the subject, many of the calls from cell phones did not include information allowing the caller to be located. Chances of getting as close as 100 feet (30 metres) were higher in areas with more towers. But if a call was made from a large building, even that would not be enough to precisely locate the caller. New federal rules, which service providers helped with, require location information for 40 percent of calls by 2017 and 80 percent by 2021.[37]

As of 2018, 80 percent of 9-1-1 calls in the United States were made on cell phones, but the ability to do so by text messaging was not required. Text-to-911 was first used in Iowa in 2009. According to the FCC, only 1,600 of about 6,000 9-1-1 call centers had the ability, up from 650 in 2016.[38]

Certain cell phone operating systems allow users to access local emergency services by calling any country's version of 9-1-1.[39]

Internet telephony

If 9-1-1 is dialed from a commercial Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) service, depending on how the provider handles such calls, the call may not go anywhere at all, or it may go to a non-emergency number at the public safety answering point associated with the billing or service address of the caller.[40] Because a VoIP adapter can be plugged into any broadband internet connection, a caller could be hundreds or even thousands of miles away from home, yet if the call goes to an answering point at all, it would be the one associated with the caller's address and not the actual location of the call. It may never be possible to reliably and accurately identify the location of a VoIP user, even if a GPS receiver is installed in the VoIP adapter, since such phones are normally used indoors, and thus may be unable to get a signal.

In March 2005, commercial Internet telephony provider Vonage was sued by the Texas Attorney General, who alleged that their website and other sales and service documentation did not make clear enough that Vonage's provision of 9-1-1 service was not done traditionally. In May 2005, the FCC issued an order requiring VoIP providers to offer 9-1-1 service to all their subscribers within 120 days of the order being published.[2] In Canada, the federal regulators have required Internet service providers (ISPs) to provide an equivalent service to the conventional PSAPs, but even these encounter problems with caller location, since their databases rely on company billing addresses.[41]

In May 2010, most VoIP users who dial 9-1-1 are connected to a call center owned by their telephone company, or contracted by them. The operators are most often not trained emergency service providers and are only there to do their best to connect the caller to the appropriate emergency service. If the call center can determine the location of the emergency they try to transfer the caller to the appropriate PSAP. Most often the caller ends up being directed to a PSAP in the general area of the emergency. A 9-1-1 operator at that PSAP must then determine the location of the emergency.

VoIP services operating in Canada are required to provide 9-1-1 emergency service.[42] In April 2008, an 18-month-old boy in Calgary, Alberta, died after a Toronto VoIP provider's 9-1-1 operator had an ambulance dispatched to the address of the family's previous abode in Mississauga, Ontario.[43]

Emergencies across jurisdictions

When a caller dials 9-1-1, the call is routed to the local public safety answering point. However, if the caller is reporting an emergency in another jurisdiction, the dispatchers may or may not know how to contact the proper authorities. The publicly posted phone numbers for most police departments in the U.S. are non-emergency numbers that often specifically instruct callers to dial 9-1-1 in case of emergency, which does not resolve the issue for callers outside of the jurisdiction.

NENA has developed the North American 9-1-1 Resource Database which includes the National PSAP Registry. PSAPs can query this database to obtain emergency contact information of a PSAP in another county or state when it receives a call involving another jurisdiction. Online access to this database is provided at no charge for authorized local and state 9-1-1 authorities.[44]

See also

- 3-1-1, non-emergency number

- 9-1-1 Tapping Protocol

- N11 code

- Dial 1119, a 1950 MGM feature film that portrays "1119" as a police emergency number

- eCall

- Emergency medical dispatcher

- Emergency telephone

- Emergency telephone number

- Enhanced 9-1-1

- Friendly caller program

- In Case of Emergency

- Next Generation 9-1-1

- Reverse 9-1-1

- Text-to-9-1-1

References

- "911, 108 and 112 are the world's standard emergency numbers, ITU decides". The Verge. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- "9-1-1 Service". Federal Communications Commission. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved October 9, 2015.

- "9-1-1 Services". Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. August 24, 2015. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved October 9, 2015.

- "911 Philippines is ready!". Manila Bulletin. MB. Archived from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- "999 celebrates its 70th birthday". BT plc. June 29, 2007. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- "911 and E911 Services". Federal Communications Commission. February 14, 2011. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- "Today in History". News and Record. February 16, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2021 – via Associated Press.

- "SPVM History". Service de police de la Ville de Montréal. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- "9-1-1 Origin & History". National Emergency Number Association. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- "Winnipeg Police History website". Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- "Winnipegers Call 999 for Help CBC Digital Archives website". CBC News. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- HISTORY OF 911: AMERICA'S EMERGENCY SERVICE, BEFORE AND AFTER KITTY GENOVESE Archived May 20, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, January 19, 2017, by Carolyn Abate in Beyond the Films, PBS website.

- How the Death of Kitty Genovese Birthed 911 and Neighborhood Watches Archived May 20, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, insideedition.com.

- Adoption Of 911 Archived May 20, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Case Exit, April 2, 2018

- The murder of "Kitty" Genovese that led to the Bystander Effect & the 911 system Archived May 20, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, June 8, 2018, Kristin Thomas.

- Kitty Genovese Archived May 20, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, August 21, 2018, history.com

- Allen, Gary. "History of 911". Dispatch Magazine. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- "Illinois Bell to offer 911 system to suburbs". Chicago Tribune. April 23, 1981. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- Thomas Powers, William Recktenwald (April 6, 1984). "Suburbs scurrying to get quick-dial emergency systems". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- Cekay, Thomas (April 2, 1989). "911 service becomes No. 1 on suburb referendum list". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- "9-1-1 Statistics". National Emergency Number Association. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- "Community Directory – Fire/Emergency Numbers". Government of Nunavut. Archived from the original on February 16, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- Robertson, Grant (December 19, 2008). "Canada's 9-1-1 emergency". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on November 23, 2009. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- Cohen, Sidney. "'Growing pains' expected when N.W.T.'s 911 service goes live on Monday". CBC. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- "AT&T and State of Tennessee to Launch Text to 9-1-1 Trial". PR Newswire. September 5, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- "Mexico will start first phase of emergency 911 in October". The Yucatan Times. August 8, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- "Por primera vez México cuenta con datos sobre llamadas al 911". La Razón (in Mexican Spanish). July 24, 2017. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- "Washington State Legislature website". Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- "U.S. Patent#6526125 (PatentStorm website)". Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- "Emergency Gateway Datasheet" (PDF). 911 Enable. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 14, 2012.

- "Range of 911 User Fees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 30, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- "TELEPHONE PENETRATION BY INCOME BY STATE" (PDF). Fcc.gov. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- "Denton County (Ga.) 9-1-1 website". Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- "Calling 9-1-1 (City of Calgary website)". Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- "Old cell phones give dispatchers headache". Deseret News. April 23, 2007.

- "9-1-1 Wireless Services". Federal Communications Commission. May 26, 2011. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- Boyle, John (February 24, 2015). "Calling 9-1-1 on a cell? They won't know your address". Asheville Citizen-Times. p. A1.

- Anderson, Mae (October 31, 2018). "Why is it so hard to text 911?". Associated Press. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- Earl, Jennifer (March 22, 2017). "iPhone users warned about potentially dangerous "Siri 108" prank". CBS News. CBS Interactive. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- "911VoIp FAQs". Archived from the original on March 17, 2005. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- "CRTC Decision on 9-1-1 Emergency Services for VoIP Service Providers" (Press release). Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. April 4, 2005. Archived from the original on April 6, 2009. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- "Telecom Decision CRTC 2005–21". Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. Government of Canada. April 4, 2005. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- "Calgary toddler dies after family calls 9-1-1 on internet phone". CBC News. April 30, 2008. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- "NENA 9-1-1 Resource DB". Archived from the original on October 8, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

External links

- 9-1-1 Services, Web site of 9-1-1 Services in Canada.

- 911.gov, Web site of the 911 Program in the United States.