Aseptic meningitis

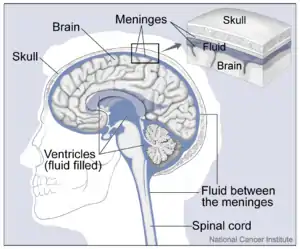

Aseptic meningitis is the inflammation of the meninges, a membrane covering the brain and spinal cord, in patients whose cerebral spinal fluid test result is negative with routine bacterial cultures. Aseptic meningitis is caused by viruses, mycobacteria, spirochetes, fungi, medications, and cancer malignancies.[1] The testing for both meningitis and aseptic meningitis is mostly the same. A cerebrospinal fluid sample is taken by lumbar puncture and is tested for leukocyte levels to determine if there is an infection and goes on to further testing to see what the actual cause is. The symptoms are the same for both meningitis and aseptic meningitis but the severity of the symptoms and the treatment can depend on the certain cause.

| Aseptic meningitis | |

|---|---|

| |

| The anatomical structure of the human brain. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

The most common cause of aseptic meningitis is by viral infection. Other causes may include side-effects from drugs and connective tissue disorders.

Signs and symptoms

Aseptic meningitis is a disease that can depend on the patient's age, however, research has shown some distinct symptoms that indicate the possibility of aseptic meningitis. A variety of patients notice a change in body temperatures (higher than normal temperatures 38-40 °C), marked with the possibility of vomiting, headaches, firm neck pain, and even lack of appetite. In younger patients, like babies, a meningeal inflammation can be noticed along with the possibility of hepatic necrosis and myocarditis. In serious cases, a multiple organ failure can also signal aseptic meningitis and oftentimes, in babies, seizures and focal neurological deficits can be early symptoms of aseptic meningitis. In fact, in newborns, the mortality rate is 70%. The next set of age group, like children, have similar but varying symptoms of sore throat, rashes, and diarrhea. In adults, symptoms and the harshness of them tend to be less in duration. Additionally, the probability of developing aseptic meningitis increases when patients have a case of mumps or herpes.[2]

Symptoms of meningitis caused by an acute viral infection last between one and two weeks. When aseptic meningitis is caused by cytomegalovirus 20 percent of individuals face mortality or morbidity. If left untreated it can affect an individual's hearing and learning abilities.[3]

Causes

The most common cause of aseptic meningitis is a viral infection, specifically by enteroviruses. In fact, 90 percent of all meningitis cases that are viral are caused by enteroviruses.[2] Other viruses that may cause aseptic meningitis are varicella zoster virus, herpes, and mumps.[4] Other causes may include mycobacteria, fungi, spirochetes, and complications from HIV. Side effects of certain drugs such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antibiotics (e.g., trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or amoxicillin), and antiepileptic drugs can also cause aseptic meningitis.[1]

There are multiple types of aseptic meningitis that are differentiated based on their cause.

- Viral meningitis

An example of a mumps infection.

An example of a mumps infection.- Enterovirus (EV) caused meningitis. This is the most common cause of viral meningitis, with 90% of viral meningitis cases being caused by EVs.[2]

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

- Mumps meningoencephalitis

- Mosquito carried viruses of the flavivirus family. Saint Louis encephalitis (SLE) and West Nile virus (WNV) are the most typical.[2]

- Specific types of Herpes can result in aseptic meningitis. These are (HSV)-1, (HSV)-2, varicella-zoster virus, and (HHV6).[2]

- Bacteria

- Fungi

- Drug-induced aseptic meningitis (DIAM)

- Autoimmune diseases

- Cancer-caused aseptic meningitis such as neoplastic meningitis

- This affects about 5% of all cancer cases, with a predominance in leukemias.[2]

- Neurosarcoidosis

Diagnosis

The term aseptic can be misleading, implying a lack of infection. On the contrary, many cases of aseptic meningitis represent infection with viruses or mycobacteria that cannot be detected with routine methods. Medical professionals will take into consideration the season of the year, the medical history of the individual and family, physical examination, and laboratory results when diagnosing aseptic meningitis.[3]

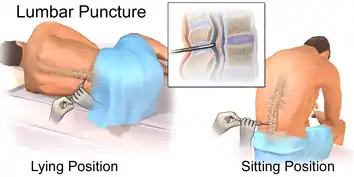

One common medical test used when diagnosing aseptic meningitis is lumbar puncture.[3] A medical professional inserts a needle between two vertebrae to remove cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the spinal cord.[6] The cerebrospinal fluid collected from the lumbar puncture is analyzed by microscope examination or by culture to distinguish between bacterial and aseptic meningitis. Samples of CSF undergo cell count, Gram stains, and viral cultures, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Polymerase chain reaction has increased the ability of clinicians to detect viruses such as enterovirus, cytomegalovirus, and herpes virus in the CSF, but many viruses can still escape detection. Other laboratory tests include blood, urine, and stool collection. Medical professionals also have the option of performing a computed tomographic (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), these tests help observe calcifications or abscesses.[3]

Treatment

If CSF levels are irregular among individuals, they will undergo hospitalization where they receive antiviral therapy. If aseptic meningitis was caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV), the individual will receive acyclovir, an antiviral drug.[3] If infants are diagnosed, medical professionals will order regular check-ins for hearing and learning disabilities.

History

Aseptic meningitis was first described by Wallgren in 1925.[7] Aseptic meningitis cases have varied historically. Aseptic meningitis caused by mumps has declined in the United States due to the increased use of vaccination which prevents mumps cases from occurring.[2]

References

- Tunkel, Allan R. "Aseptic meningitis in adults". UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer Health. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- Irani DN (August 2008). "Aseptic meningitis and viral myelitis". Neurologic Clinics. 26 (3): 635–55, vii–viii. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2008.03.003. PMC 2728900. PMID 18657719.

- Norris CM, Danis PG, Gardner TD (May 1999). "Aseptic meningitis in the newborn and young infant". American Family Physician. 59 (10): 2761–70. PMID 10348069.

- Bamberger DM (2010-12-15). "Diagnosis, Initial Management, and Prevention of Meningitis". American Family Physician. 82 (12): 1491–1498. ISSN 0002-838X. PMID 21166369.

- Jolles S, Sewell WA, Leighton C (March 2000). "Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: diagnosis and management". Drug Safety. 22 (3): 215–26. doi:10.2165/00002018-200022030-00005. PMID 10738845. S2CID 8023888.

- "Lumbar puncture (spinal tap) - About - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- Hasbun R (August 2000). "The Acute Aseptic Meningitis Syndrome". Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2 (4): 345–351. doi:10.1007/s11908-000-0014-z. PMID 11095876. S2CID 20078472.