Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), also known as cervical dysplasia, is the abnormal growth of cells on the surface of the cervix that could potentially lead to cervical cancer.[1] More specifically, CIN refers to the potentially precancerous transformation of cells of the cervix.

| Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cervical dysplasia |

| |

| Positive visual inspection with acetic acid of the cervix for CIN-1 | |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

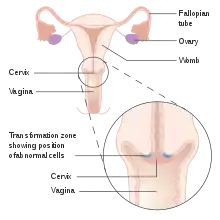

CIN most commonly occurs at the squamocolumnar junction of the cervix, a transitional area between the squamous epithelium of the vagina and the columnar epithelium of the endocervix.[2] It can also occur in vaginal walls and vulvar epithelium. CIN is graded on a 1–3 scale, with 3 being the most abnormal (see classification section below).

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is necessary for the development of CIN, but not all with this infection develop cervical cancer.[3] Many women with HPV infection never develop CIN or cervical cancer. Typically, HPV resolves on its own.[4] However, those with an HPV infection that lasts more than one or two years have a higher risk of developing a higher grade of CIN.[5]

Like other intraepithelial neoplasias, CIN is not cancer and is usually curable.[3] Most cases of CIN either remain stable or are eliminated by the person's immune system without need for intervention. However, a small percentage of cases progress to cervical cancer, typically cervical squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), if left untreated.[6]

Signs and symptoms

There are no specific symptoms of CIN alone.

Generally, signs and symptoms of cervical cancer include:[7]

- abnormal or post-menopausal bleeding

- abnormal discharge

- changes in bladder or bowel function

- pelvic pain on examination

- abnormal appearance or palpation of cervix.

HPV infection of the vulva and vagina can cause genital warts or be asymptomatic.

Causes

The cause of CIN is chronic infection of the cervix with HPV, especially infection with high-risk HPV types 16 or 18. It is thought that the high-risk HPV infections have the ability to inactivate tumor suppressor genes such as the p53 gene and the RB gene, thus allowing the infected cells to grow unchecked and accumulate successive mutations, eventually leading to cancer.[1]

Some groups of women have been found to be at a higher risk of developing CIN:[1][8]

- Infection with a high-risk type of HPV, such as 16, 18, 31, or 33

- Immunodeficiency (e.g. HIV infection)

- Poor diet

- Multiple sex partners

- Lack of condom use

- Cigarette smoking

Additionally, a number of risk factors have been shown to increase an individual's likelihood of developing CIN 3/carcinoma in situ (see below):[9]

- Women who give birth before age 17

- Women who have > 1 full term pregnancies

Pathophysiology

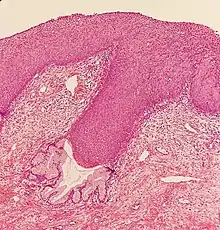

The earliest microscopic change corresponding to CIN is epithelial dysplasia, or surface lining, of the cervix, which is essentially undetectable by the woman. The majority of these changes occur at the squamocolumnar junction, or transformation zone, an area of unstable cervical epithelium that is prone to abnormal changes.[2] Cellular changes associated with HPV infection, such as koilocytes, are also commonly seen in CIN. While infection with HPV is needed for development of CIN, most women with HPV infection do not develop high-grade intraepithelial lesions or cancer. HPV is not alone enough causative.[10]

Of the over 100 different types of HPV, approximately 40 are known to affect the epithelial tissue of the anogenital area and have different probabilities of causing malignant changes.[11]

Diagnosis

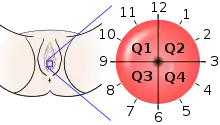

A test for HPV called the Digene HPV test is highly accurate and serves as both a direct diagnosis and adjuvant to the Pap smear, which is a screening device that allows for an examination of cells but not tissue structure, needed for diagnosis. A colposcopy with directed biopsy is the standard for disease detection. Endocervical brush sampling at the time of Pap smear to detect adenocarcinoma and its precursors is necessary along with doctor/patient vigilance on abdominal symptoms associated with uterine and ovarian carcinoma. The diagnosis of CIN or cervical carcinoma requires a biopsy for histological analysis.

Classification

_normal_squamous_epithelium.jpg.webp)

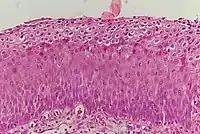

Historically, abnormal changes of cervical epithelial cells were described as mild, moderate, or severe epithelial dysplasia. In 1988 the National Cancer Institute developed "The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical/Vaginal Cytologic Diagnoses".[12] This system provides a uniform way to describe abnormal epithelial cells and determine specimen quality, thus providing clear guidance for clinical management. These abnormalities were classified as squamous or glandular and then further classified by the stage of dysplasia: atypical cells, mild, moderate, severe, and carcinoma.[13]

Depending on several factors and the location of the lesion, CIN can start in any of the three stages and can either progress or regress.[1] The grade of squamous intraepithelial lesion can vary.

CIN is classified in grades:[14]

| Histology Grade | Corresponding Cytology | Description | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIN 1 (Grade I) | Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) |

|

%252C_Cervical_Biopsy_(3776284166).jpg.webp) |

| CIN 2/3 | High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) |

|

|

| CIN 2 (Grade II) |

|

_CIN2.jpg.webp) | |

| CIN 3 (Grade III) |

|

|

Changes in Terminology

The College of American Pathology and the American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology came together in 2012 to publish changes in terminology to describe HPV-associated squamous lesions of the anogenital tract as LSIL or HSIL as follows below:[16]

CIN 1 is referred to as LSIL.

CIN 2 that is negative for p16, a marker for high-risk HPV, is referred to as LSIL. Those that are p16-positive are referred to as HSIL.

CIN 3 is referred to as HSIL.

Screening

The two screening methods available are the Pap smear and testing for HPV.CIN is usually discovered by a screening test, the Pap smear. The purpose of this test is to detect potentially precancerous changes through random sampling of the transformation zone. Pap smear results may be reported using the Bethesda system (see above). The sensitivity and specificity of this test were variable in a systematic review looking at accuracy of the test. An abnormal Pap smear result may lead to a recommendation for colposcopy of the cervix, an in office procedure during which the cervix is examined under magnification. A biopsy is taken of any abnormal appearing areas.

Colposcopy can be painful and so researchers have tried to find which pain relief is best for women with CIN to use. Research suggests that compared to a placebo, the injection of a local anaesthetic and vasoconstrictor (medicine that causes blood vessels to narrow) into the cervix may lower blood loss and pain during colposcopy.[17]

HPV testing can identify most of the high-risk HPV types responsible for CIN. HPV screening happens either as a co-test with the Pap smear or can be done after a Pap smear showing abnormal cells, called reflex testing. Frequency of screening changes based on guidelines from the Society of Lower Genital Tract Disorders (ASCCP). The World Health Organization also has screening and treatment guidelines for precancerous cervical lesions and prevention of cervical cancer.

Primary prevention

HPV vaccination is the approach to primary prevention of both CIN and cervical cancer.

| Vaccine | HPV Genotypes Protected Against | Who Gets It? | Number of Doses | Timing Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gardasil - quadrivalent | 6, 11 (cause genital warts) 16, 18 (cause ~70% of cervical cancers)[18] | females and males age 9-26 | 3 | before sexual debut or shortly thereafter |

| Cervarix - bivalent | 16, 18 | females age 9-25 | 3 | |

| Gardasil 9 - nonavalent vaccine | 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58 (cause ~20% of cervical cancers)[19] | females and males ages 9–26 | 3 |

It is important to note that these vaccines do not protect against 100% of types of HPV known to cause cancer. Therefore, screening is still recommended in vaccinated individuals.

Secondary prevention

Appropriate management with monitoring and treatment is the approach to secondary prevention of cervical cancer in cases of persons with CIN.

Treatment

Treatment for CIN 1, mild dysplasia, is not recommended if it lasts fewer than two years.[20] Usually, when a biopsy detects CIN 1, the woman has an HPV infection, which may clear on its own within 12 months. Therefore, it is instead followed for later testing rather than treated.[20] In young women closely monitoring CIN 2 lesions also appears reasonable.[6]

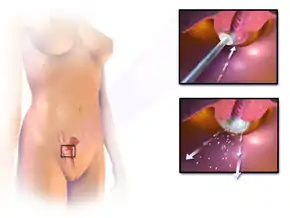

Treatment for higher-grade CIN involves removal or destruction of the abnormal cervical cells by cryocautery, electrocautery, laser cautery, loop electrical excision procedure (LEEP), or cervical conization. The typical threshold for treatment is CIN 2+, although a more restrained approach may be taken for young persons and pregnant persons. A Cochrane review found no clear evidence to show which surgical technique may be superior for treating CIN.[21] Evidence suggests that while retinoids are not effective in preventing the progression of CIN, they may be effective in causing regression of disease in people with CIN2.[22] Therapeutic vaccines are currently undergoing clinical trials. The lifetime recurrence rate of CIN is about 20%, but it isn't clear what proportion of these cases are new infections rather than recurrences of the original infection.

Research to investigate if prophylactic antibiotics can help prevent infection in women undergoing excision of the cervical transformation zone found a lack of quality evidence.[23]

Surgical treatment of CIN lesions is associated with an increased risk of infertility or subfertility. A case-control study found that there is an approximately two-fold increase in risk i.[24]

The findings of low quality observational studies suggest that women receiving treatment for CIN during pregnancy may be at an increased risk of premature birth.[25][26] People with HIV and CIN 2+ should be initially managed according to the recommendations for the general population according to the 2012 updated ASCCP consensus guidelines.[27]

Outcomes

It used to be thought that cases of CIN progressed through grades 1–3 toward cancer in a linear fashion.[28][29][30]

However most CIN spontaneously regress. Left untreated, about 70% of CIN 1 will regress within one year; 90% will regress within two years.[31] About 50% of CIN 2 cases will regress within two years without treatment.

Progression to cervical carcinoma in situ (CIS) occurs in approximately 11% of CIN 1 and 22% of CIN 2 cases. Progression to invasive cancer occurs in approximately 1% of CIN 1, 5% of CIN 2, and at least 12% of CIN 3 cases.[3]

Progression to cancer typically takes 15 years with a range of 3 to 40 years. Also, evidence suggests that cancer can occur without first detectably progressing through CIN grades and that a high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia can occur without first existing as a lower grade.[1][28][32]

Research suggests that treatment does not affect the chances of getting pregnant but it is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage in the second trimester.[33]

Epidemiology

Between 250,000 and 1 million American women are diagnosed with CIN annually. Women can develop CIN at any age, however women generally develop it between the ages of 25 to 35.[1] The estimated annual incidence of CIN in the United States among persons who undergo screening is 4% for CIN 1 and 5% for CIN 2 and CIN 3.[34]

References

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 718–721. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- "Colposcopy and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a beginners manual". screening.iarc.fr. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

- Section 4 Gynecologic Oncology > Chapter 29. Preinvasive Lesions of the Lower Genital Tract > Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia in:Bradshaw KD, Schorge JO, Schaffer J, Halvorson LM, Hoffman BG (2008). Williams' Gynecology. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-147257-9.

- "Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer". www.who.int. Retrieved 2018-12-18.

- Boda D, Docea AO, Calina D, Ilie MA, Caruntu C, Zurac S, Neagu M, Constantin C, Branisteanu DE, Voiculescu V, Mamoulakis C, Tzanakakis G, Spandidos DA, Drakoulis N, Tsatsakis AM (March 2018). "Human papilloma virus: Apprehending the link with carcinogenesis and unveiling new research avenues (Review)". International Journal of Oncology. 52 (3): 637–655. doi:10.3892/ijo.2018.4256. PMC 5807043. PMID 29393378.

- Tainio K, Athanasiou A, Tikkinen KA, Aaltonen R, Cárdenas J, Glazer-Livson S, et al. (February 2018). "Clinical course of untreated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 under active surveillance: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 360: k499. doi:10.1136/bmj.k499. PMC 5826010. PMID 29487049.

- DiSaia PJ, Creasman WT (2007). "Invasive cervical cancer.". Clinical Gynecologic Oncology (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier. p. 55.

- Heard I (January 2009). "Prevention of cervical cancer in women with HIV". Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 4 (1): 68–73. doi:10.1097/COH.0b013e328319bcbe. PMID 19339941. S2CID 25047280.

- International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer (2006-09-01). "Cervical carcinoma and reproductive factors: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 16,563 women with cervical carcinoma and 33,542 women without cervical carcinoma from 25 epidemiological studies". International Journal of Cancer. 119 (5): 1108–1124. doi:10.1002/ijc.21953. ISSN 0020-7136. PMID 16570271. S2CID 29433753.

- Beutner KR, Tyring S (May 1997). "Human papillomavirus and human disease". The American Journal of Medicine. 102 (5A): 9–15. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00178-2. PMID 9217657.

- de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, zur Hausen H (June 2004). "Classification of papillomaviruses". Virology. 324 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.033. PMID 15183049.

- Soloman D (1989). "The 1988 Bethesda System for reporting cervical/vaginal cytologic diagnoses: developed and approved at the National Cancer Institute workshop in Bethesda, MD, December 12-13, 1988". Diagnostic Cytopathology. 5 (3): 331–4. doi:10.1002/dc.2840050318. PMID 2791840. S2CID 19684695.

- Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O'Connor D, Prey M, et al. (April 2002). "The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology". JAMA. 287 (16): 2114–9. doi:10.1001/jama.287.16.2114. PMID 11966386.

- Melnikow J, Nuovo J, Willan AR, Chan BK, Howell LP (October 1998). "Natural history of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions: a meta-analysis". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 92 (4 Pt 2): 727–35. doi:10.1097/00006250-199810001-00046. PMID 9764690.

- Nagi CS, Schlosshauer PW (August 2006). "Endocervical glandular involvement is associated with high-grade SIL". Gynecologic Oncology. 102 (2): 240–3. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.12.029. PMID 16472847.

- Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Thomas Cox J, Heller DS, Henry MR, Luff RD, et al. (January 2013). "The Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology Standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology". International Journal of Gynecological Pathology. 32 (1): 76–115. doi:10.1097/PGP.0b013e31826916c7. PMID 23202792. S2CID 205943774.

- Gajjar K, Martin-Hirsch PP, Bryant A, Owens GL (July 2016). "Pain relief for women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia undergoing colposcopy treatment". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7: CD006120. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006120.pub4. PMC 6457789. PMID 27428114.

- Lowy DR, Schiller JT (May 2006). "Prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 116 (5): 1167–73. doi:10.1172/JCI28607. PMC 1451224. PMID 16670757.

- "FDA approves Gardasil 9 for prevention of certain cancers caused by five additional types of HPV". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (press release). 10 December 2014. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, retrieved August 1, 2013

- Martin-Hirsch, Pierre PL; Paraskevaidis, Evangelos; Bryant, Andrew; Dickinson, Heather O (2013-12-04). "Surgery for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (12): CD001318. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001318.pub3. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 4170911. PMID 24302546.

- Helm, C. William; Lorenz, Douglas J; Meyer, Nicholas J; Rising, William WR; Wulff, Judith L (2013-06-06). "Retinoids for preventing the progression of cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD003296. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003296.pub3. ISSN 1465-1858. PMID 23740788.

- Kietpeerakool C, Chumworathayi B, Thinkhamrop J, Ussahgij B, Lumbiganon P (January 2017). "Antibiotics for infection prevention after excision of the cervical transformation zone". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD009957. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009957.pub2. PMC 6464760. PMID 28109160.

- Kyrgiou M, Koliopoulos G, Martin-Hirsch P, Arbyn M, Prendiville W, Paraskevaidis E (February 2006). "Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for intraepithelial or early invasive cervical lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 367 (9509): 489–98. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68181-6. PMID 16473126. S2CID 31397277.

- Kyrgiou M, Athanasiou A, Paraskevaidi M, Mitra A, Kalliala I, Martin-Hirsch P, et al. (July 2016). "Adverse obstetric outcomes after local treatment for cervical preinvasive and early invasive disease according to cone depth: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 354: i3633. doi:10.1136/bmj.i3633. PMC 4964801. PMID 27469988.

- Kyrgiou M, Athanasiou A, Kalliala IE, Paraskevaidi M, Mitra A, Martin-Hirsch PP, et al. (November 2017). "Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for cervical intraepithelial lesions and early invasive disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD012847. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012847. PMC 6486192. PMID 29095502.

- Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, Katki HA, Kinney WK, Schiffman M, et al. (April 2013). "2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors". Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 17 (5 Suppl 1): S1–S27. doi:10.1097/LGT.0b013e318287d329. PMID 23519301. S2CID 12551963.

- Agorastos T, Miliaras D, Lambropoulos AF, Chrisafi S, Kotsis A, Manthos A, Bontis J (July 2005). "Detection and typing of human papillomavirus DNA in uterine cervices with coexistent grade I and grade III intraepithelial neoplasia: biologic progression or independent lesions?". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 121 (1): 99–103. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.11.024. PMID 15949888.

- Hillemanns P, Wang X, Staehle S, Michels W, Dannecker C (February 2006). "Evaluation of different treatment modalities for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN): CO(2) laser vaporization, photodynamic therapy, excision and vulvectomy". Gynecologic Oncology. 100 (2): 271–5. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.08.012. PMID 16169064.

- Rapp L, Chen JJ (August 1998). "The papillomavirus E6 proteins". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer. 1378 (1): F1-19. doi:10.1016/s0304-419x(98)00009-2. PMID 9739758.

- Bosch FX, Burchell AN, Schiffman M, Giuliano AR, de Sanjose S, Bruni L, Tortolero-Luna G, Kjaer SK, Muñoz N (August 2008). "Epidemiology and natural history of human papillomavirus infections and type-specific implications in cervical neoplasia". Vaccine. 26 Suppl 10 (Supplement 10): K1-16. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.064. PMID 18847553. 18847553.

- Monnier-Benoit S, Dalstein V, Riethmuller D, Lalaoui N, Mougin C, Prétet JL (March 2006). "Dynamics of HPV16 DNA load reflect the natural history of cervical HPV-associated lesions". Journal of Clinical Virology. 35 (3): 270–7. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2005.09.001. PMID 16214397.

- Kyrgiou M, Mitra A, Arbyn M, Paraskevaidi M, Athanasiou A, Martin-Hirsch PP, et al. (September 2015). Cochrane Gynaecological, Neuro-oncology and Orphan Cancer Group (ed.). "Fertility and early pregnancy outcomes after conservative treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (9): CD008478. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008478.pub2. PMC 6457639. PMID 26417855.

- Insinga RP, Glass AG, Rush BB (July 2004). "Diagnoses and outcomes in cervical cancer screening: a population-based study". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 191 (1): 105–13. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.043. PMID 15295350.