Coma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to respond normally to painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal wake-sleep cycle and does not initiate voluntary actions.[1] Coma patients exhibit a complete absence of wakefulness and are unable to consciously feel, speak or move.[2][3] Comas can be derived by natural causes, or can be medically induced.[4]

| Coma | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Neurology, psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Unconsciousness |

| Complications | Persistent vegetative state, death |

| Duration | Can vary from a few days to several years (longest recorded is 42 years) |

Clinically, a coma can be defined as the inability consistently to follow a one-step command.[5][6] It can also be defined as a score of ≤ 8 on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) lasting ≥ 6 hours.[7] For a patient to maintain consciousness, the components of wakefulness and awareness must be maintained. Wakefulness describes the quantitative degree of consciousness, whereas awareness relates to the qualitative aspects of the functions mediated by the cortex, including cognitive abilities such as attention, sensory perception, explicit memory, language, the execution of tasks, temporal and spatial orientation and reality judgment.[2][8] From a neurological perspective, consciousness is maintained by the activation of the cerebral cortex—the gray matter that forms the outer layer of the brain—and by the reticular activating system (RAS), a structure located within the brainstem.[9][10]

Etymology

The term 'coma', from the Greek κῶμα koma, meaning deep sleep, had already been used in the Hippocratic corpus (Epidemica) and later by Galen (second century AD). Subsequently, it was hardly used in the known literature up to the middle of the 17th century. The term is found again in Thomas Willis' (1621–1675) influential De anima brutorum (1672), where lethargy (pathological sleep), 'coma' (heavy sleeping), carus (deprivation of the senses) and apoplexy (into which carus could turn and which he localized in the white matter) are mentioned. The term carus is also derived from Greek, where it can be found in the roots of several words meaning soporific or sleepy. It can still be found in the root of the term 'carotid'. Thomas Sydenham (1624–89) mentioned the term 'coma' in several cases of fever (Sydenham, 1685).[11][12]

Signs and symptoms

General symptoms of a person in a comatose state are:

- Inability to voluntarily open the eyes

- A non-existent sleep-wake cycle

- Lack of response to physical (painful) or verbal stimuli

- Depressed brainstem reflexes, such as pupils not responding to light

- Irregular breathing

- Scores between 3 and 8[13] on the Glasgow Coma Scale[1]

Causes

Many types of problems can cause a coma. Forty percent of comatose states result from drug poisoning.[14] Certain drug use under certain conditions can damage or weaken the synaptic functioning in the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) and keep the system from properly functioning to arouse the brain.[15] Secondary effects of drugs, which include abnormal heart rate and blood pressure, as well as abnormal breathing and sweating, may also indirectly harm the functioning of the ARAS and lead to a coma. Given that drug poisoning is the cause for a large portion of patients in a coma, hospitals first test all comatose patients by observing pupil size and eye movement, through the vestibular-ocular reflex. (See Diagnosis below.)[15]

The second most common cause of coma, which makes up about 25% of cases, is lack of oxygen, generally resulting from cardiac arrest.[14] The Central Nervous System (CNS) requires a great deal of oxygen for its neurons. Oxygen deprivation in the brain, also known as hypoxia, causes sodium and calcium from outside of the neurons to decrease and intracellular calcium to increase, which harms neuron communication.[16] Lack of oxygen in the brain also causes ATP exhaustion and cellular breakdown from cytoskeleton damage and nitric oxide production.

Twenty percent of comatose states result from the side effects of a stroke.[14] During a stroke, blood flow to part of the brain is restricted or blocked. An ischemic stroke, brain hemorrhage, or tumor may cause restriction of blood flow. Lack of blood to cells in the brain prevents oxygen from getting to the neurons, and consequently causes cells to become disrupted and die. As brain cells die, brain tissue continues to deteriorate, which may affect the functioning of the ARAS.

The remaining 15% of comatose cases result from trauma, excessive blood loss, malnutrition, hypothermia, hyperthermia, hyperammonemia,[17] abnormal glucose levels, and many other biological disorders. Furthermore, studies show that 1 out of 8 patients with traumatic brain injury experience a comatose state.[18]

Pathophysiology

Injury to either or both of the cerebral cortex or the reticular activating system (RAS) is sufficient to cause a person to enter coma.[19]

The cerebral cortex is the outer layer of neural tissue of the cerebrum of the brain.[20] The cerebral cortex is composed of gray matter which consists of the nuclei of neurons, whereas the inner portion of the cerebrum is composed of white matter and is composed of the axons of neuron.[21] White matter is responsible for perception, relay of the sensory input via the thalamic pathway, and many other neurological functions, including complex thinking.

The RAS, on the other hand, is a more primitive structure in the brainstem which includes the reticular formation (RF).[22] The RAS has two tracts, the ascending and descending tract. The ascending tract, or ascending reticular activating system (ARAS), is made up of a system of acetylcholine-producing neurons, and works to arouse and wake up the brain.[23] Arousal of the brain begins from the RF, through the thalamus, and then finally to the cerebral cortex.[15] Any impairment in ARAS functioning, a neuronal dysfunction, along the arousal pathway stated directly above, prevents the body from being aware of its surroundings.[22] Without the arousal and consciousness centers, the body cannot awaken, remaining in a comatose state.[24]

The severity and mode of onset of coma depends on the underlying cause. There are two main subdivisions of a coma: structural and diffuse neuronal.[25] A structural cause, for example, is brought upon by a mechanical force that brings about cellular damage, such as physical pressure or a blockage in neural transmission.[26] While a diffuse cause is limited to aberrations of cellular function, that fall under a metabolic or toxic subgroup. Toxin-induced comas are caused by extrinsic substances, whereas metabolic-induced comas are caused by intrinsic processes, such as body thermoregulation or ionic imbalances(e.g. sodium).[24] For instance, severe hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) or hypercapnia (increased carbon dioxide levels in the blood) are examples of a metabolic diffuse neuronal dysfunction. Hypoglycemia or hypercapnia initially cause mild agitation and confusion, but progress to obtundation, stupor, and finally, complete unconsciousness.[27] In contrast, coma resulting from a severe traumatic brain injury or subarachnoid hemorrhage can be instantaneous. The mode of onset may therefore be indicative of the underlying cause.[1]

Structural and diffuse causes of coma are not isolated from one another, as one can lead to the other in some situations. For instance, coma induced by a diffuse metabolic process, such as hypoglycemia, can result in a structural coma if it is not resolved. Another example is if cerebral edema, a diffuse dysfunction, leads to ischemia of the brainstem, a structural issue, due to the blockage of the circulation in the brain.[24]

Diagnosis

Although diagnosis of coma is simple, investigating the underlying cause of onset can be rather challenging. As such, after gaining stabilization of the patient's airways, breathing and circulation (the basic ABCs) various diagnostic tests, such as physical examinations and imaging tools (CT scan, MRI, etc.) are employed to access the underlying cause of the coma.[28]

When an unconscious person enters a hospital, the hospital utilizes a series of diagnostic steps to identify the cause of unconsciousness.[29] According to Young,[15] the following steps should be taken when dealing with a patient possibly in a coma:

- Perform a general examination and medical history check

- Make sure the patient is in an actual comatose state and is not in a locked-in state or experiencing psychogenic unresponsiveness. Patients with locked-in syndrome present with voluntary movement of their eyes, whereas patients with psychogenic comas demonstrate active resistance to passive opening of the eyelids, with the eyelids closing abruptly and completely when the lifted upper eyelid is released (rather than slowly, asymmetrically and incompletely as seen in comas due to organic causes).[30]

- Find the site of the brain that may be causing coma (e.g., brainstem, back of brain...) and assess the severity of the coma with the Glasgow Coma Scale

- Take blood work to see if drugs were involved or if it was a result of hypoventilation/hyperventilation

- Check for levels of serum glucose, calcium, sodium, potassium, magnesium, phosphate, urea, and creatinine

- Perform brain scans to observe any abnormal brain functioning using either CT or MRI scans

- Continue to monitor brain waves and identify seizures of patient using EEGs

Initial evaluation

In the initial assessment of coma, it is common to gauge the level of consciousness on the AVPU (alert, vocal stimuli, painful stimuli, unresponsive) scale by spontaneously exhibiting actions and, assessing the patient's response to vocal and painful stimuli.[31] More elaborate scales, such as the Glasgow Coma Scale, quantify an individual's reactions such as eye opening, movement and verbal response in order to indicate their extent of brain injury.[32] The patient's score can vary from a score of 3 (indicating severe brain injury and death) to 15 (indicating mild or no brain injury).[33]

In those with deep unconsciousness, there is a risk of asphyxiation as the control over the muscles in the face and throat is diminished. As a result, those presenting to a hospital with coma are typically assessed for this risk ("airway management"). If the risk of asphyxiation is deemed high, doctors may use various devices (such as an oropharyngeal airway, nasopharyngeal airway or endotracheal tube) to safeguard the airway.

Imaging and testing

Imaging basically encompasses computed tomography (CAT or CT) scan of the brain, or MRI for example, and is performed to identify specific causes of the coma, such as hemorrhage in the brain or herniation of the brain structures.[34] Special tests such as an EEG can also show a lot about the activity level of the cortex such as semantic processing,[35] presence of seizures, and are important available tools not only for the assessment of the cortical activity but also for predicting the likelihood of the patient's awakening.[36] The autonomous responses such as the skin conductance response may also provide further insight on the patient's emotional processing.[37]

In the treatment of traumatic brain injury (TBI), there are 4 examination methods that have proved useful: skull x-ray, angiography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[38] The skull x-ray can detect linear fractures, impression fractures (expression fractures) and burst fractures.[39] Angiography is used on rare occasions for TBIs i.e. when there is suspicion of an aneurysm, carotid sinus fistula, traumatic vascular occlusion, and vascular dissection.[40] A CT can detect changes in density between the brain tissue and hemorrhages like subdural and intracerebral hemorrhages. MRIs are not the first choice in emergencies because of the long scanning times and because fractures cannot be detected as well as CT. MRIs are used for the imaging of soft tissues and lesions in the posterior fossa which cannot be found with the use of CT.[41]

Body movements

Assessment of the brainstem and cortical function through special reflex tests such as the oculocephalic reflex test (doll's eyes test), oculovestibular reflex test (cold caloric test), corneal reflex, and the gag reflex.[42] Reflexes are a good indicator of what cranial nerves are still intact and functioning and is an important part of the physical exam. Due to the unconscious status of the patient, only a limited number of the nerves can be assessed. These include the cranial nerves number 2 (CN II), number 3 (CN III), number 5 (CN V), number 7 (CN VII), and cranial nerves 9 and 10 (CN IX, CN X).

| Type of reflex | Description |

|---|---|

| Oculocephalic reflex | Oculocephalic reflex, also known as the doll's eye, is performed to assess the integrity of the brainstem.

|

| Pupillary light reflex | Pupil reaction to light is important because it shows an intact retina, and cranial nerve number 2 (CN II)

|

| Oculovestibular reflex (Cold Caloric Test) |

Caloric reflex test also evaluates both cortical and brainstem function

|

| Corneal reflex | The corneal reflex assesses the proper function of the trigeminal nerve (CN 5) and facial nerve (CN 7), and is present at infancy.

|

| Gag reflex | The gag, or pharyngeal, reflex is centered in the medulla and consists of the reflexive motor response of pharyngeal elevation and constriction with tongue retraction in response to sensory stimulation of the pharyngeal wall, posterior tongue, tonsils, or faucial pillars.

|

Assessment of posture and physique is the next step. It involves general observation about the patient's positioning. There are often two stereotypical postures seen in comatose patients. Decorticate posturing is a stereotypical posturing in which the patient has arms flexed at the elbow, and arms adducted toward the body, with both legs extended. Decerebrate posturing is a stereotypical posturing in which the legs are similarly extended (stretched), but the arms are also stretched (extended at the elbow). The posturing is critical since it indicates where the damage is in the central nervous system. A decorticate posturing indicates a lesion (a point of damage) at or above the red nucleus, whereas a decerebrate posturing indicates a lesion at or below the red nucleus. In other words, a decorticate lesion is closer to the cortex, as opposed to a decerebrate posturing which indicates that the lesion is closer to the brainstem.

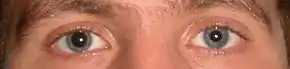

Pupil size

Pupil assessment is often a critical portion of a comatose examination, as it can give information as to the cause of the coma; the following table is a technical, medical guideline for common pupil findings and their possible interpretations:[9]

| Pupil sizes (left eye vs. right eye) | Possible interpretation |

|---|---|

| Normal eye with two pupils equal in size and reactive to light. This means that the patient is probably not in a coma and is probably lethargic, under influence of a drug, or sleeping. |

| "Pinpoint" pupils indicate heroin or opiate overdose, which can be responsible for a patient's coma. The pinpoint pupils are still reactive to light bilaterally (in both eyes, not just one). Another possibility is damage to the pons.[9] |

| One pupil is dilated and unreactive, while the other is normal (in this case, the right eye is dilated, while the left eye is normal in size). This could mean damage to the oculomotor nerve (cranial nerve number 3, CN III) on the right side, or indicate the possibility of vascular involvement. |

| Both pupils are dilated and unreactive to light. This could be due to overdose of certain medications, hypothermia or severe anoxia (lack of oxygen). |

Severity

A coma can be classified as (1) supratentorial (above Tentorium cerebelli), (2) infratentorial (below Tentorium cerebelli), (3) metabolic or (4) diffused.[9] This classification is merely dependent on the position of the original damage that caused the coma, and does not correlate with severity or the prognosis. The severity of coma impairment however is categorized into several levels. Patients may or may not progress through these levels. In the first level, the brain responsiveness lessens, normal reflexes are lost, the patient no longer responds to pain and cannot hear.

The Rancho Los Amigos Scale is a complex scale that has eight separate levels, and is often used in the first few weeks or months of coma while the patient is under closer observation, and when shifts between levels are more frequent.

Treatment

Treatment for people in a coma will depend on the severity and cause of the comatose state. Upon admittance to an emergency department, coma patients will usually be placed in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) immediately,[15] where maintenance of the patient's respiration and circulation become a first priority. Stability of their respiration and circulation is sustained through the use of intubation, ventilation, administration of intravenous fluids or blood and other supportive care as needed.

Continued care

Once a patient is stable and no longer in immediate danger, there may be a shift of priority from stabilizing the patient to maintaining the state of their physical wellbeing. Moving patients every 2–3 hours by turning them side to side is crucial to avoiding bed sores as a result of being confined to a bed. Moving patients through the use of physical therapy also aids in preventing atelectasis, contractures or other orthopedic deformities which would interfere with a coma patient's recovery.[45]

Pneumonia is also common in coma patients due to their inability to swallow which can then lead to aspiration. A coma patient's lack of a gag reflex and use of a feeding tube can result in food, drink or other solid organic matter being lodged within their lower respiratory tract (from the trachea to the lungs). This trapping of matter in their lower respiratory tract can ultimately lead to infection, resulting in aspiration pneumonia.[45]

Coma patients may also deal with restlessness or seizures. As such, soft cloth restraints may be used to prevent them from pulling on tubes or dressings and side rails on the bed should be kept up to prevent patients from falling.[45]

Caregivers

Coma has a wide variety of emotional reactions from the family members of the affected patients, as well as the primary care givers taking care of the patients. Research has shown that the severity of injury causing coma was found to have no significant impact compared to how much time has passed since the injury occurred.[46] Common reactions, such as desperation, anger, frustration, and denial are possible. The focus of the patient care should be on creating an amicable relationship with the family members or dependents of a comatose patient as well as creating a rapport with the medical staff.[47] Although there is heavy importance of a primary care taker, secondary care takers can play a supporting role to temporarily relieve the primary care taker's burden of tasks.

Prognosis

Comas can last from several days to, in particularly extreme cases, years. Some patients eventually gradually come out of the coma, some progress to a vegetative state, and others die. Some patients who have entered a vegetative state go on to regain a degree of awareness; and in some cases may remain in vegetative state for years or even decades (the longest recorded period is 42 years).[48][49]

Predicted chances of recovery will differ depending on which techniques were used to measure the patient's severity of neurological damage. Predictions of recovery are based on statistical rates, expressed as the level of chance the person has of recovering. Time is the best general predictor of a chance of recovery. For example, after four months of coma caused by brain damage, the chance of partial recovery is less than 15%, and the chance of full recovery is very low.[50]

The outcome for coma and vegetative state depends on the cause, location, severity and extent of neurological damage. A deeper coma alone does not necessarily mean a slimmer chance of recovery; similarly, a milder coma does not indicate a higher chance of recovery. The most common cause of death for a person in a vegetative state is secondary infection such as pneumonia, which can occur in patients who lie still for extended periods.

Recovery

People may emerge from a coma with a combination of physical, intellectual, and psychological difficulties that need special attention. It is common for coma patients to awaken in a profound state of confusion and experience dysarthria, the inability to articulate any speech. Recovery is usually gradual. In the first days, the patient may only awaken for a few minutes, with increased duration of wakefulness as their recovery progresses, and they may eventually recover full awareness. That said, some patients may never progress beyond very basic responses.[51]

There are reports of people coming out of a coma after long periods of time. After 19 years in a minimally conscious state, Terry Wallis spontaneously began speaking and regained awareness of his surroundings.[52]

A man with brain-damage and trapped in a coma-like state for six years, was brought back to consciousness in 2003 by doctors who planted electrodes deep inside his brain. The method, called deep brain stimulation (DBS), successfully roused communication, complex movement and eating ability in the 38-year-old American man with a traumatic brain injury. His injuries left him in a minimally conscious state, a condition akin to a coma but characterized by occasional, but brief, evidence of environmental and self-awareness that coma patients lack.[53]

Society and culture

Research by Dr. Eelco Wijdicks on the depiction of comas in movies was published in Neurology in May 2006. Dr. Wijdicks studied 30 films (made between 1970 and 2004) that portrayed actors in prolonged comas, and he concluded that only two films accurately depicted the state of a coma patient and the agony of waiting for a patient to awaken: Reversal of Fortune (1990) and The Dreamlife of Angels (1998). The remaining 28 were criticized for portraying miraculous awakenings with no lasting side effects, unrealistic depictions of treatments and equipment required, and comatose patients remaining muscular and tanned.[54]

Bioethics

A person in a coma is said to be in an unconscious state. Perspectives on personhood, identity and consciousness come into play when discussing the metaphysical and bioethical views on comas.

It has been argued that unawareness should be just as ethically relevant and important as a state of awareness and that there should be metaphysical support of unawareness as a state.[55]

In the ethical discussions about disorders of consciousness (DOCs), two abilities are usually considered as central: experiencing well-being and having interest. Well-being can broadly be understood as the positive effect related to what makes life good (according to specific standards) for the individual in question.[56] The only condition for well-being broadly considered is the ability to experience its ‘positiveness’. That said, because experiencing positiveness is a basic emotional process with phylogenetic roots, it is likely to occur at a completely unaware level and therefore, introduces the idea of an unconscious well-being.[55] As such, the ability of having interests, is crucial for describing two abilities which those with comas are deficient in. Having an interest in a certain domain can be understood as having a stake in something that can affect what makes our life good in that domain. An interest is what directly and immediately improves life from a certain point of view or within a particular domain, or greatly increases the likelihood of life improvement enabling the subject to realize some good.[56] That said, sensitivity to reward signals is a fundamental element in the learning process, both consciously and unconsciously.[57] Moreover, the unconscious brain is able to interact with its surroundings in a meaningful way and to produce meaningful information processing of stimuli coming from the external environment, including other people.[58]

According to Hawkins, "1. A life is good if the subject is able to value, or more basically if the subject is able to care. Importantly, Hawkins stresses that caring has no need for cognitive commitment, i.e. for high-level cognitive activities: it requires being able to distinguish something, track it for a while, recognize it over time, and have certain emotional dispositions vis-à-vis something. 2. A life is good if the subject has the capacity for relationship with others, i.e. for meaningfully interacting with other people."[56] This suggests that unawareness may (at least partly) fulfill both conditions identified by Hawkins for life to be good for a subject, thus making the unconscious ethically relevant.[58]

See also

- Brain death, lack of activity in both cortex, and lack of brainstem function

- Coma scale, a system to assess the severity of coma

- Locked-in syndrome, paralysis of most muscles, except ocular muscles of the eyes, while patient is conscious

- Persistent vegetative state (vegetative coma), deep coma without detectable awareness. Damage to the cortex, with an intact brainstem.

- Process Oriented Coma Work, for an approach to working with residual consciousness in comatose patients.

- Suspended animation, the inducement of a temporary cessation or decay of main body functions.

References

- Weyhenmyeye, James A.; Eve A. Gallman (2007). Rapid Review Neuroscience 1st Ed. Mosby Elsevier. pp. 177–9. ISBN 978-0-323-02261-3.

- Bordini, A.L.; Luiz, T.F.; Fernandes, M.; Arruda, W. O.; Teive, H. A. (2010). "Coma scales: a historical review". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 68 (6): 930–937. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2010000600019. PMID 21243255.

- Cooksley, Tim; Holland, Mark (2017-02-01). "The management of coma". Medicine. 45 (2): 115–119. doi:10.1016/j.mpmed.2016.12.001. ISSN 1357-3039.

- Marc Lallanilla (2013-09-06). "What Is a Medically Induced Coma?". livescience.com. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- "The Glasgow structured approach to assessment of the Glasgow Coma Scale". www.glasgowcomascale.org. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- "Coma - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- "Glasgow Coma Scale - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- Laureys; Boly; Moonen; Maquet (2009). "Coma" (PDF). Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. 2: 1133–1142. doi:10.1016/B978-008045046-9.01770-8. ISBN 9780080450469. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-10-20.

- Hannaman, Robert A. (2005). MedStudy Internal Medicine Review Core Curriculum: Neurology 11th Ed. MedStudy. pp. (11–1) to (11–2). ISBN 1-932703-01-2.

- "Persistent vegetative state: A medical minefield". New Scientist: 40–3. July 7, 2007. See diagram Archived 2017-08-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Coma Origin". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- Wijdicks, Eelco F. M.; Koehler, Peter J. (2008-03-01). "Historical study of coma: looking back through medical and neurological texts". Brain. 131 (3): 877–889. doi:10.1093/brain/awm332. ISSN 0006-8950. PMID 18208847.

- Russ Rowlett. "Glasgow Coma Scale". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 2018-06-04. Retrieved 2010-12-07.

- Liversedge, Timothy; Hirsch, Nicholas (2010). "Coma". Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine. 11 (9): 337–339. doi:10.1016/j.mpaic.2010.05.008.

- Young, G.B. (2009). "Coma". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1157 (1): 32–47. Bibcode:2009NYASA1157...32Y. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04471.x. PMID 19351354. S2CID 222086047.

- Busl, K. M.; Greer, D. M. (2010). "Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury: Pathophysiology, neuropathology and mechanisms". NeuroRehabilitation. 26 (1): 5–13. doi:10.3233/NRE-2010-0531. PMID 20130351.

- Ali, Rimsha; Nagalli, Shivaraj (2022). "Hyperammonemia". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32491436.

- Lombardi, Francesco FL; Taricco, Mariangela; De Tanti, Antonio; Telaro, Elena; Liberati, Alessandro (2002-04-22). "Sensory stimulation for brain injured individuals in coma or vegetative state". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD001427. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001427. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 7045727. PMID 12076410.

- "Coma - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- S., Saladin, Kenneth (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780073525600. OCLC 318191613.

- Mercadante, Anthony A.; Tadi, Prasanna (2022), "Neuroanatomy, Gray Matter", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31990494, retrieved 2022-04-23

- Arguinchona, Joseph H.; Tadi, Prasanna (2022), "Neuroanatomy, Reticular Activating System", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31751025, retrieved 2022-04-23

- "Ascending Reticular Activating System - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- Traub, Stephen J.; Wijdicks, Eelco F. (2016). "Initial Diagnosis and Management of Coma". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 34 (4): 777–793. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2016.06.017. ISSN 1558-0539. PMID 27741988.

- Huff, J. Stephen; Tadi, Prasanna (2022), "Coma", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28613473, retrieved 2022-04-23

- Miller, Margaret A.; Zachary, James F. (2017). "Mechanisms and Morphology of Cellular Injury, Adaptation, and Death". Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease: 2–43.e19. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-35775-3.00001-1. ISBN 9780323357753. PMC 7171462.

- "Obtundation, stupor and coma Peter Dickinson", Small Animal Neurological Emergencies, CRC Press, pp. 140–155, 2012-03-15, doi:10.1201/b15214-12, ISBN 978-0-429-15897-1, retrieved 2022-04-23

- Thim, Troels; Krarup, Niels Henrik Vinther; Grove, Erik Lerkevang; Rohde, Claus Valter; Løfgren, Bo (2012-01-31). "Initial assessment and treatment with the Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure (ABCDE) approach". International Journal of General Medicine. 5: 117–121. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S28478. ISSN 1178-7074. PMC 3273374. PMID 22319249.

- "First aid for unconsciousness: What to do and when to seek help". www.medicalnewstoday.com. 2021-06-11. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- Baxter, Cynthia L.; White, William D. (September 2003). "Psychogenic Coma: Case Report". The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 33 (3): 317–322. doi:10.2190/yvp4-3gtc-0ewk-42e8. ISSN 0091-2174. PMID 15089013. S2CID 34123071.

- Romanelli, David; Farrell, Mitchell W. (2022), "AVPU Score", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30860702, retrieved 2022-04-23

- Jain, Shobhit; Iverson, Lindsay M. (2022), "Glasgow Coma Scale", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30020670, retrieved 2022-04-23

- "Classification and Complications of Traumatic Brain Injury: Practice Essentials, Epidemiology, Pathophysiology". 2022-02-07.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Haupt, Walter F; Hansen, Hans Christian; Janzen, Rudolf W C; Firsching, Raimund; Galldiks, Norbert (2015-04-16). "Coma and cerebral imaging". SpringerPlus. 4: 180. doi:10.1186/s40064-015-0869-y. ISSN 2193-1801. PMC 4424227. PMID 25984436.

- Daltrozzo J.; Wioland N.; Mutschler V.; Lutun P.; Jaeger A.; Calon B.; Meyer A.; Pottecher T.; Lang S.; Kotchoubey B. (2009c). "Cortical Information Processing in Coma" (PDF). Cognitive & Behavioral Neurology. 22 (1): 53–62. doi:10.1097/wnn.0b013e318192ccc8. PMID 19372771. S2CID 2278000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-14. Retrieved 2011-05-11.

- Daltrozzo J.; Wioland N.; Mutschler V.; Kotchoubey B. (2007). "Predicting Coma and other Low Responsive Patients Outcome using Event-Related Brain Potentials: A Meta-analysis" (PDF). Clinical Neurophysiology. 118 (3): 606–614. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2006.11.019. PMID 17208048. S2CID 41389741. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-14. Retrieved 2011-05-11.

- Daltrozzo J.; Wioland N.; Mutschler V.; Lutun P.; Calon B.; Meyer A.; Jaeger A.; Pottecher T.; Kotchoubey B. (2010a). "Electrodermal Response in Coma and Other Low Responsive Patients" (PDF). Neuroscience Letters. 475 (1): 44–47. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2010.03.043. PMID 20346390. S2CID 24525307. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-14. Retrieved 2011-05-11.

- Lee, Bruce; Newberg, Andrew (April 2005). "Neuroimaging in Traumatic Brain Imaging". NeuroRx. 2 (2): 372–383. doi:10.1602/neurorx.2.2.372. ISSN 1545-5343. PMC 1064998. PMID 15897957.

- Nakahara, Kuniaki; Shimizu, Satoru; Utsuki, Satoshi; Oka, Hidehiro; Kitahara, Takao; Kan, Shinichi; Fujii, Kiyotaka (January 2011). "Linear fractures occult on skull radiographs: a pitfall at radiological screening for mild head injury". The Journal of Trauma. 70 (1): 180–182. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d76737. ISSN 1529-8809. PMID 20495486.

- Korkmazer, Bora; Kocak, Burak; Tureci, Ercan; Islak, Civan; Kocer, Naci; Kizilkilic, Osman (2013-04-28). "Endovascular treatment of carotid cavernous sinus fistula: A systematic review". World Journal of Radiology. 5 (4): 143–155. doi:10.4329/wjr.v5.i4.143. ISSN 1949-8470. PMC 3647206. PMID 23671750.

- Haupt, Walter F; Hansen, Hans Christian; Janzen, Rudolf W C; Firsching, Raimund; Galldiks, Norbert (2015). "Coma and cerebral imaging". SpringerPlus. 4 (1): 180. doi:10.1186/s40064-015-0869-y. ISSN 2193-1801. PMC 4424227. PMID 25984436.

- "Neurological Assessment Tips". London Health Sciences Centre. 2014.

- Textbook of clinical neurology. Goetz, Christopher G. (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: WB Saunders. 2007. ISBN 9781416036180. OCLC 785829292.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Hermanowicz, Neal (2007), "Cranial Nerves IX (Glossopharyngeal) and X (Vagus)", Textbook of Clinical Neurology, Elsevier, pp. 217–229, doi:10.1016/b978-141603618-0.10013-x, ISBN 9781416036180

- "Coma" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-27. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- Qadeer, Anam; Khalid, Usama; Amin, Mahwish; Murtaza, Sajeela; Khaliq, Muhammad F; Shoaib, Maria (2017-08-21). "Caregiver's Burden of the Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury". Cureus. 9 (8): e1590. doi:10.7759/cureus.1590. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 5650257. PMID 29062622.

- Coma Care (2010-03-30). "Caring for Care Giver and Family". Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- Edwarda O’Bara, who spent 4 decades in a coma, dies at 59

- Aruna Shanba, who spent 42 years in coma.

- Formisano R; Carlesimo GA; Sabbadini M; et al. (May 2004). "Clinical predictors and neuropleropsychological outcome in severe traumatic brain injury patients". Acta Neurochir (Wien). 146 (5): 457–62. doi:10.1007/s00701-004-0225-4. PMID 15118882. S2CID 43537443.

- NINDS (October 29, 2010). "Coma Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)". Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- "Mother stunned by coma victim's unexpected words". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2003-07-12.

- "Electrodes stir man from six-year coma-like state". Cosmos Magazine. 2 August 2007. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Eelco F.M. Wijdicks, MD; Coen A. Wijdicks, BS (2006). "The portrayal of coma in contemporary motion pictures". Neurology. 66 (9): 1300–1303. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000210497.62202.e9. PMID 16682658. S2CID 43411074. Retrieved 2009-11-25.

- Farisco, Michele; Evers, Kathinka (December 2017). "The ethical relevance of the unconscious". Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine. 12 (1): 11. doi:10.1186/s13010-017-0053-9. ISSN 1747-5341. PMC 5747178. PMID 29284489.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - Hawkins, Jennifer (2016-03-01), "What Is Good for Them? Best Interests and Severe Disorders of Consciousness", Finding Consciousness, Oxford University Press, pp. 180–206, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190280307.003.0011, ISBN 9780190280307

- "Henry Adams: The Middle Years. By <italic>Ernest Samuels</italic>. (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 1958. Pp. xiv, 514. $7.50.) and Henry Adams: The Major Phase. By <italic>Ernest Samuels</italic>. (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 1964. Pp. xv, 687. $10.00.)". The American Historical Review. January 1966. doi:10.1086/ahr/71.2.709. ISSN 1937-5239.

- Farisco, Michele (2016-04-28). Farisco, Michele; Evers, Kathinka (eds.). Neurotechnology and Direct Brain Communication. doi:10.4324/9781315723983. ISBN 9781315723983.