Congenital syphilis

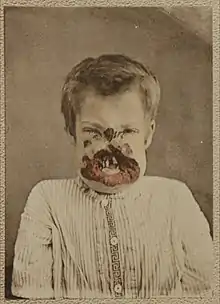

Congenital syphilis is syphilis present in utero and at birth, and occurs when a child is born to a mother with syphilis.[1] Untreated early syphilis infections results in a high risk of poor pregnancy outcomes, including saddle nose, lower extremity abnormalities, miscarriages, premature births, stillbirths, or death in newborns. Some infants with congenital syphilis have symptoms at birth, but many develop symptoms later. Symptoms may include rash, fever, an enlarged liver and spleen, and skeletal abnormalities.[1] Newborns will typically not develop a primary syphilitic chancre but may present with signs of secondary syphilis (i.e. generalized body rash). Often these babies will develop syphilitic rhinitis ("snuffles"), the mucus from which is laden with the T. pallidum bacterium, and therefore highly infectious. If a baby with congenital syphilis is not treated early, damage to the bones, teeth, eyes, ears, and brain can occur.[1]

| Congenital syphilis | |

|---|---|

| |

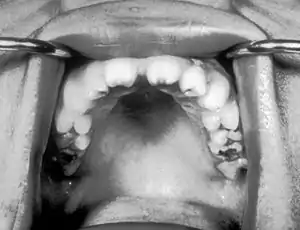

| Notched incisors known as Hutchinson's teeth which are characteristic of congenital syphilis | |

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

| Usual onset | Congenital |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Types | Early & late |

| Causes | Born to a mother with syphilis |

| Diagnostic method | Signs, symptoms, blood tests, CSF tests |

| Prevention | Adequate screening and treatment in pregnant mother |

| Treatment | Antibiotic |

| Medication | Penicillin |

Classification

Early

_(14597432110).jpg.webp)

This is a subset of cases of congenital syphilis. Newborns may be asymptomatic and are only identified on routine prenatal screening. If not identified and treated, these newborns develop poor feeding and runny nose.[1] By definition, early congenital syphilis occurs in children between 0 and 2 years old. After, they can develop late congenital syphilis.[2]

Late

Late congenital syphilis is a subset of cases of congenital syphilis. By definition, it occurs in children at or greater than 2 years of age who acquired the infection trans-placentally.[2]

Symptoms include:[3]

- Blunted upper incisor teeth known as Hutchinson's teeth

- Deafness from auditory nerve disease

- Frontal bossing (prominence of the brow ridge)

- Hard palate defect

- Inflammation of the cornea known as interstitial keratitis

- Protruding mandible

- Saber shins

- Saddle nose (collapse of the bony part of nose)

- Short maxillae

- Swollen knees

A frequently-found group of symptoms is Hutchinson's triad, which consists of Hutchinson's teeth (notched incisors), keratitis and deafness and occurs in 63% of cases.[3]

Treatment (with penicillin) before the development of late symptoms is essential.[4]

Signs and symptoms

- Abnormal x-rays

- Anemia[5]

- Cerebral palsy

- Du Bois sign, narrowing of the little finger

- Enlarged liver

- Enlarged spleen

- Frontal bossing

- Sensorineural hearing loss

- Higouménakis' sign, enlargement of the sternal end of clavicle in late congenital syphilis

- Hutchinson's triad, a set of symptoms consisting of deafness, Hutchinson's teeth (centrally notched, widely spaced peg-shaped upper central incisors), and interstitial keratitis (IK), an inflammation of the cornea which can lead to corneal scarring and potential blindness

- Hydrocephalus

- Jaundice

- Lymph node enlargement

- Mulberry molars (permanent first molars with multiple poorly developed cusps)[6]

- Musculoskeletal deformities

- Petechiae

- Poorly developed maxillae

- Pseudoparalysis

- Rhagades, linear scars at the angles of the mouth and nose result from bacterial infection of skin lesions

- Snuffles, aka "syphilitic rhinitis", which appears similar to the rhinitis of the common cold, except it is more severe, lasts longer, often involves bloody rhinorrhea, and is often associated with laryngitis[7]

- Sabre shins

- Skin rash

Death from congenital syphilis is usually due to bleeding into the lungs.

Diagnosis

Serological testing is carried out on the mother and the infant. If the neonatal IgG antibody titres are significantly higher than the mother's, then congenital syphilis can be confirmed. Specific IgM in the infant is another method of confirmation. CSF pleocytosis, raised CSF protein level and positive CSF serology suggest neurosyphilis.[8]

Treatment

If a pregnant mother is identified as being infected with syphilis, treatment can effectively prevent congenital syphilis from developing in the fetus, especially if she is treated before the sixteenth week of pregnancy. The fetus is at greatest risk of contracting syphilis when the mother is in the early stages of infection, but the disease can be passed at any point during pregnancy, even during delivery (if the child had not already contracted it). A woman in the secondary stage of syphilis decreases her fetus's risk of developing congenital syphilis by 98% if she receives treatment before the last month of pregnancy.[9] An affected child can be treated using antibiotics much like an adult; however, any developmental symptoms are likely to be permanent.[10]

Kassowitz's law is an empirical observation used in context of congenital syphilis stating that the greater the duration between the infection of the mother and conception, the better the outcome for the infant. Features of a better outcome include less chance of stillbirth and of developing congenital syphilis.[11]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends treating symptomatic or babies born to an infected mother with unknown treatment status with procaine penicillin G, 50,000 U/kg dose IM a day in a single dose for 10 days.[12] Treatment for these babies can vary on a case-by-case basis. Treatment cannot reverse any deformities, brain, or permanent tissue damage that has already occurred.[10]

A Cochrane review found that antibiotics may be effective for serological cure but in general the evidence around the effectiveness of antibiotics for congenital syphilis is uncertain due to the poor methodological quality of the small number of trials that have been conducted.[13]

References

- "Congenital syphilis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- Tsimis, Michael E.; Sheffield, Jeanne S. (2017-03-15). "Update on syphilis and pregnancy". Birth Defects Research. 109 (5): 347–352. doi:10.1002/bdra.23562. ISSN 2472-1727. PMID 28398683. S2CID 1026966.

- "Congenital Syphilis". University of Pittsburgh.

- "Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines - 2002". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2013-01-21.

- "Anemia: Overview". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- Hillson, S; Grigson, C; Bond, S (1998). "Dental defects of congenital syphilis". Am J Phys Anthropol. 107 (1): 25–40. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199809)107:1<25::AID-AJPA3>3.0.CO;2-C. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 9740299.

- Darville, T. (1 May 1999). "Syphilis". Pediatrics in Review. 20 (5): 160–165. doi:10.1542/pir.20-5-160. PMID 10233174.

- South, Mike (2012). Practical Paediatrics (7th ed.). Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. pp. 368, 830. ISBN 9780702042928.

- Congenital syphilis.

- Arnold, S; Ford-Jones, L (November–December 2000). "Congenital syphilis: A guide to diagnosis and management". Paediatrics & Child Health. 5 (8): 463–469. doi:10.1093/pch/5.8.463. PMC 2819963. PMID 20177559.

- Singh, Ameeta E.; Barbara Romanowski (1 April 1999). "Syphilis: Review with Emphasis on Clinical, Epidemiologic, and Some Biologic Features". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 12 (2): 187–209. doi:10.1128/CMR.12.2.187. PMC 88914. PMID 10194456.

- "Sexually Transmitted Diseases: Treatment Guidelines, 2010 By: the CDC". Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- Walker, GJ; Walker, D; Molano Franco, D; Grillo-Ardila, CF (15 February 2019). "Antibiotic treatment for newborns with congenital syphilis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (2): CD012071. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012071.pub2. PMC 6378924. PMID 30776081.