Corrosive substance

A corrosive substance is one that will damage or destroy other substances with which it comes into contact by means of a chemical reaction.

Etymology

The word corrosive is derived from the Latin verb corrodere, which means to gnaw, indicating how these substances seem to "gnaw" their way through flesh or other materials.

Chemical terms

The word corrosive refers to any chemical that will dissolve the structure of an object. They can be acids, oxidizers, or bases. When they come in contact with a surface, the surface deteriorates. The deterioration can happen in minutes, e.g. concentrated hydrochloric acid spilled on skin; or slowly over days or years, e.g. the rusting of iron in a bridge.

Sometimes the word caustic is used as a synonym for corrosive when referring to the effect on living tissues. At low concentrations, a corrosive substance is called an irritant, and its effect on living tissue is called irritation. At high concentrations, a corrosive substance causes a chemical burn, a distinct type of tissue damage. Corrosives are different from poisons in that corrosives are immediately dangerous to the tissues they contact, whereas poisons may have systemic toxic effects that require time to become evident. Colloquially, corrosives may be called poisons but the concepts are technically distinct. However, there is nothing which precludes a corrosive from being a poison; some substances are both corrosives and poisons.

Corrosion of non-living surfaces such as metals is a distinct process. For example, a water-air electrochemical cell corrodes iron to rust, corrodes copper to patina, and corrodes copper, silver, and other metals to tarnish.

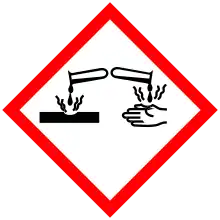

In the international system of symbolic chemical labels, both rapid corrosion of metals and chemical corrosion of skin qualify for the corrosive symbol.

Effects on living tissue

Common corrosives are either strong acids, strong bases, or concentrated solutions of certain weak acids or weak bases. They can exist as any state of matter, including liquids, solids, gases, mists or vapors.

Their action on living tissue (e.g. skin, flesh and cornea) is mainly based on acid-base reactions of amide hydrolysis, ester hydrolysis and protein denaturation. Proteins (chemically composed of amide bonds) are destroyed via amide hydrolysis while lipids (which have ester bonds) are decomposed by ester hydrolysis. These reactions lead to chemical burns and are the mechanism of the destruction posed by corrosives.

Some corrosives possess other chemical properties which may extend their corrosive effects on living tissue. For example, sulfuric acid (H2SO4) at a high concentration is also a strong dehydrating agent,[1] capable of dehydrating carbohydrates and liberating extra heat. This results in secondary thermal burns in addition to the chemical burns and may speed up its decomposing reactions on the contact surface. Some corrosives, such as nitric acid and concentrated sulfuric acid, are strong oxidizing agents as well, which significantly contributes to the extra damage caused. Hydrofluoric acid does not necessarily cause noticeable damage upon contact, but produces tissue damage and toxicity after being painlessly absorbed. Zinc chloride solutions are capable of destroying cellulose and corroding through paper and silk since the zinc cations in the solutions specifically attack hydroxyl groups, acting as a Lewis acid. This effect is not restricted to acids; so strong a base as calcium oxide, which has a strong affinity for water (forming calcium hydroxide, itself a strong and corrosive base), also releases heat capable of contributing thermal burns as well as delivering the corrosive effects of a strong alkali to moist flesh.[2]

In addition, some corrosive chemicals, mostly acids such as hydrochloric acid and nitric acid, are volatile and can emit corrosive mists upon contact with air. Inhalation can damage the respiratory tract.

Corrosive substances are most hazardous to eyesight. A drop of a corrosive may cause blindness within 2–10 seconds through opacification or direct destruction of the cornea.

Ingestion of corrosives can induce severe consequences, including serious damage of the gastrointestinal tract, which can lead to vomiting, severe stomach aches,[3] and death.

Common types

Common corrosive chemicals are classified into:

- Acids

- Strong acids – the most common are sulfuric acid, nitric acid and hydrochloric acid (H2SO4, HNO3 and HCl, respectively).

- Some concentrated weak acids, for example formic acid, acetic acid, and phosphoric acid

- Strong Lewis acids such as anhydrous aluminum chloride and boron trifluoride

- Lewis acids with specific reactivity; e.g., solutions of zinc chloride

- Extremely strong acids (superacids)

- Bases

- Caustics or alkalis, such as sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, and calcium hydroxide

- Alkali metals in the metallic form (e.g. elemental sodium), and hydrides of alkali and alkaline earth metals, such as sodium hydride, function as strong bases and hydrate to give caustics

- Extremely strong bases (superbases) such as alkoxides, metal amides (e.g. sodium amide) and organometallic bases such as butyllithium

- Fully alkalized salts of weak acids such as trisodium phosphate

- Some concentrated weak bases, such as ammonia when anhydrous or in a concentrated solution

- Dehydrating agents such as concentrated sulfuric acid, phosphorus pentoxide, calcium oxide, anhydrous zinc chloride, also elemental alkali metals

- Strong oxidizers such as concentrated hydrogen peroxide

- Electrophilic halogens: elemental fluorine, chlorine, bromine and iodine, and electrophilic salts such as sodium hypochlorite or N-chloro compounds such as chloramine-T;[4] halide ions are not corrosive, except for fluoride

- Organic halides and organic acid halides such as acetyl chloride and benzyl chloroformate

- Acid anhydrides

- Alkylating agents such as dimethyl sulfate

- Some organic materials such as phenol ("carbolic acid")

Personal protective equipment

Use of personal protective equipment, including items such as protective gloves, protective aprons, acid suits, safety goggles, a face shield, or safety shoes, is normally recommended when handling corrosive substances. Users should consult a safety data sheet for the specific recommendation for the corrosive substance of interest. The material of construction of the personal protective equipment is of critical importance as well. For example, although rubber gloves and rubber aprons may be made out of a chemically resistant elastomer such as nitrile rubber, neoprene, or butyl rubber, each of these materials has different resistance to different corrosives and they should not be substituted for each other.

Uses

Some corrosive chemicals are valued for various uses, the most common of which is in household cleaning agents. For example, most drain cleaners contain either acids or alkalis due to their capabilities of dissolving greases, proteins or mineral deposits such as limescale inside water pipes.[5]

In chemical uses, high chemical reactivity is often desirable, as the rates of chemical reactions depend on the activity (effective concentration) of the reactive species. For instance, catalytic sulfuric acid is used in the alkylation process in an oil refinery: the activity of carbocations, the reactive intermediate, is higher with stronger acidity, and thus the reaction proceeds faster. Once used, corrosives are most often recycled or neutralized. However, there have been environmental problems with untreated corrosive effluents or accidental discharges.

References

- "Sulfuric acid – uses". Archived from the original on 2013-05-09.

- "CALCIUM OXIDE". hazard.com. Archived from the original on 2012-05-01. Retrieved 2015-12-18.

- "Acid ingestion survivors recall ordeal". The Hindu. Special Correspondent. 2018-09-10. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2018-09-11.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "International Chemical Safety Card for Chloramine-T". Cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-01-06. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- "Drain and Waste systems cleaners". Archived from the original on 2013-02-20. Retrieved 2013-01-01.