De Quervain syndrome

De Quervain syndrome is mucoid degeneration[6] of two tendons that control movement of the thumb and their tendon sheath.[3] This results in pain and tenderness on the thumb side of the wrist.[3] Radial abduction of the thumb is painful.[7] On occasion, there is uneven movement or triggering the thumb with radial abduction.[4] Symptoms can come on gradually or be noted suddenly.[4]

| de Quervain Syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Potentially misleading names related to speculative causes: BlackBerry thumb, texting thumb, gamer's thumb, washerwoman's sprain, mother's wrist, mommy thumb, designer's thumb. Variations on eponymic or anatomical names: radial styloid tenosynovitis, de Quervain disease, de Quervain tendinopathy, de Quervain tenosynovitis. |

| |

| The modified Eichoff maneuver, commonly referred to as the Finkelstein's test. The arrow mark indicates where the pain is worsened in de Quervain syndrome.[1][2] | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Hand surgery, Plastic surgery, Orthopedic surgery. |

| Symptoms | Pain and tenderness on the thumb side of the wrist[3] |

| Usual onset | Gradual[4] |

| Risk factors | Repetitive movements, trauma, rheumatic diseases[4][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and examination[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Base of thumb Osteoarthritis[4] |

| Treatment | Pain medications, splinting the wrist and thumb[4] |

| Frequency | c. 1%[5] |

There is speculation that the problem is related to use of the hand, but this is not supported by experimental evidence.[8][9] Humans tend to misinterpret painful activities as causing the problem to get worse and this misinterpretation is associated with greater pain intensity.[10] For this reason, it's better not to blame activity without strong scientific support.

The diagnosis is generally based on symptoms and physical examination.[3] Diagnosis is supported if pain increases when the wrist is bent inwards while a person is grabbing their thumb within a fist.[4]

There is some evidence that the natural history of de Quervain tendinopathy is resolution over a period of about 1 year.[11] Symptomatic alleviation (palliative treatment) is provided mainly by splinting the thumb and wrist. Pain medications such as NSAIDs can also be considered.[4] Steroid injections are commonly used, but are not proved to alter the natural history of the condition. Surgery to release the first dorsal component is an option.[4] It may be most common in middle age.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms are pain and tenderness at the radial side of the wrist, fullness or thickening over the thumb side of the wrist, and difficulty gripping with the affected side of the hand. The onset is often gradual.[2] Pain is made worse by movement of the thumb and wrist, and may radiate to the thumb or the forearm.[2]

Causes

The cause of de Quervain's disease is not established. Evidence regarding a possible relation with activity and occupation is debated.[12][13] A systematic review of potential risk factors discussed in the literature did not find any evidence of a causal relationship with activity or occupation.[14] However, researchers in France found personal and work-related factors were associated with de Quervain's disease in the working population; wrist bending and movements associated with the twisting or driving of screws were the most significant of the work-related factors.[15] Proponents of the view that De Quervain syndrome is a repetitive strain injury[16] consider postures where the thumb is held in abduction and extension to be predisposing factors.[12] Workers who perform rapid repetitive activities involving pinching, grasping, pulling or pushing have been considered at increased risk.[13] These movements are associated with many types of repetitive housework such as chopping vegetables, stirring and scrubbing pots, vacuuming, cleaning surfaces, drying dishes, pegging out washing, mending clothes, gardening, harvesting and weeding. Specific activities that have been postulated as potential risk factors include intensive computer mouse use, trackball use,[12] and typing, as well as some pastimes, including bowling, golf, fly-fishing, piano-playing, sewing, and knitting.[13]

Women are diagnosed more often than men.[13] The syndrome commonly occurs during and, even more so, after pregnancy.[17] Contributory factors may include hormonal changes, fluid retention and—again, more debatably and potentially harmfully—increased housework and lifting.[17][18]

Pathophysiology

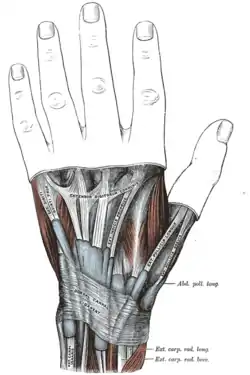

De Quervain syndrome involves noninflammatory thickening of the tendons and the synovial sheaths that the tendons run through. The two tendons concerned are those of the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus muscles. These two muscles run side by side and function to bring the thumb away from the hand (radial abduction); the extensor pollicis brevis brings the thumb outwards radially, and the abductor pollicis longus brings the thumb forward away from the palm. De Quervain tendinopathy affects the tendons of these muscles as they pass from the forearm into the hand via a fibro-osseous tunnel (the first dorsal compartment). Evaluation of histopathological specimens shows a thickening and myxoid degeneration consistent with a chronic degenerative process, as opposed to inflammation.[19] The pathology is identical in de Quervain seen in new mothers.[20]

Diagnosis

De Quervain syndrome is diagnosed clinically, based on history and physical examination, though diagnostic imaging such as X-ray may be used to rule out fracture, arthritis, or other causes, based on the person's history and presentation. The modified Eichoff maneuver, commonly referred to as the Finkelstein test, is a physical exam maneuver used to diagnose de Quervain syndrome.[2] To perform the test, the examiner grasps and ulnar deviates the hand when the person has their thumb held within their fist.[1][2] If sharp pain occurs along the distal radius (top of forearm, about an inch below the wrist), de Quervain's syndrome is likely. While a positive Finkelstein test is often considered pathognomonic for de Quervain syndrome, the maneuver can also cause some pain in those with osteoarthritis at the base of the thumb.[2]

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnoses[21] include:

- Osteoarthritis of the trapezio-metacarpal joint

- Intersection syndrome—pain will be more towards the middle of the back of the forearm and about 2–3 inches below the wrist, usually with associated crepitus.

- Wartenberg's syndrome: The primary symptom is paresthesia (numbness/tingling).

Treatment

Most tendinoses and enthesopathies are self-limiting and the same is likely to be true of de Quervain's although further study is needed.

As with many musculoskeletal conditions, the management of de Quervain's disease is determined more by convention than scientific data. A systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2013 found that corticosteroid injection seems to be an effective form of conservative management of de Quervain's syndrome in approximately 50% of patients, although more research is needed regarding the extent of any clinical benefits.[22] Efficacy data are relatively sparse and it is not clear whether benefits affect the overall natural history of the illness. One of the most common causes of corticosteroid injection failure are subcompartments of the extensor pollicis brevis tendon.[23]

Palliative treatments include a splint that immobilized the wrist and the thumb to the interphalangeal joint and anti-inflammatory medication or acetaminophen. Systematic review and meta-analysis do not support the use of splinting over steroid injections.[24][25]

Surgery (in which the sheath of the first dorsal compartment is opened longitudinally) is documented to provide relief in most patients.[26] The most important risk is to the radial sensory nerve. A small incision is made and the dorsal extensor retinaculum is identified. Once it has been identified the release is performed longitudinally along the tendon. This is done to prevent potential subluxation of the 1st compartment tendons. Next the abductor pollicis longus (APL) and extensor pollicis brevis (EPB) are identified and the compartments are released.[23]

Some occupational and physical therapists suggest alternative lifting mechanics based on the theory that the condition is due to repetitive use of the thumbs during lifting. Physical/Occupational therapy can suggest activities to avoid based on the theory that certain activities might exacerbate one's condition, as well as instruct on strengthening exercises based on the theory that this will contribute to better form and use of other muscle groups, which might limit irritation of the tendons.

Some occupational and physical therapists use other treatments, in conjunction with Therapeutic Exercises, based on the rationale that they reduce inflammation and pain and promote healing: UST, SWD, or other deep heat treatments, as well as TENS, acupuncture, or infrared light therapy, and cold laser treatments. However, the pathology of the condition is not inflammatory changes to the synovial sheath and inflammation is secondary to the condition from friction.[27] Teaching patients to reduce their secondary inflammation does not treat the underlying condition but may reduce their pain; which is helpful when trying to perform the prescribed exercise interventions.

History

From the original description of the illness in 1895 until the first description of corticosteroid injection by Jarrod Ismond in 1955,[28] it appears that the only treatment offered was surgery.[28][29][30] Since approximately 1972, the prevailing opinion has been that of McKenzie (1972) who suggested that corticosteroid injection was the first line of treatment and surgery should be reserved for unsuccessful injections.[31]

Eponym

It is named after the Swiss surgeon Fritz de Quervain who first identified it in 1895.[32] It should not be confused with de Quervain's thyroiditis, another condition named after the same person.

Society and culture

BlackBerry thumb is a neologism that refers to a form of repetitive strain injury (RSI) caused by the frequent use of the thumbs to press buttons on PDAs, smartphones, or other mobile devices. The name of the condition comes from the BlackBerry, a brand of smartphone that debuted in 1999,[33] although there are numerous other similar eponymous conditions that exist such as "Wiiitis",[34] "Nintendinitis",[35] "Playstation thumb", "texting thumb",[36] "cellphone thumb",[37] "smartphone thumb", "Android thumb", and "iPhone thumb". The medical name for the condition is De Quervain syndrome and is associated with the tendons connected to the thumb through the wrist. Causes for the condition extend beyond smartphones and gaming consoles to include activities like golf, racket sports, and lifting.[38]

Symptoms of BlackBerry thumb include aching and throbbing pain in the thumb and wrist.[39] In severe cases, it can lead to temporary disability of the affected hand, particularly the ability to grip objects.[40]

One hypothesis is that the thumb does not have the dexterity the other four fingers have and is therefore not well-suited to high speed touch typing.[41]

See also

- Mobile phone overuse

- Nomophobia

References

- Campbell, William Wesley; DeJong, Russell N. (2005). DeJong's the Neurologic Examination. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 583. ISBN 9780781727679.

- Ilyas A, Ast M, Schaffer AA, Thoder J (2007). "De quervain tenosynovitis of the wrist". J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 15 (12): 757–64. doi:10.5435/00124635-200712000-00009. PMID 18063716.

- "De Quervain's Tendinosis - Symptoms and Treatment - OrthoInfo - AAOS". December 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Hubbard, MJ; Hildebrand, BA; Battafarano, MM; Battafarano, DF (June 2018). "Common Soft Tissue Musculoskeletal Pain Disorders". Primary Care. 45 (2): 289–303. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2018.02.006. PMID 29759125.

- Satteson, Ellen; Tannan, Shruti C. (2018). De Quervain Tenosynovitis. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28723034.

- Satteson, Ellen; Tannan, Shruti C. (2022), "De Quervain Tenosynovitis", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28723034, retrieved 12 July 2022

- "De Quervain Tenosynovitis - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- Satteson, Ellen; Tannan, Shruti C. (2022), "De Quervain Tenosynovitis", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28723034, retrieved 21 July 2022

- "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- Das De, Soumen; Vranceanu, Ana-Maria; Ring, David C. (2 January 2013). "Contribution of kinesophobia and catastrophic thinking to upper-extremity-specific disability". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 95 (1): 76–81. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.00064. ISSN 1535-1386. PMID 23283376.

- "de Quervain Tenosynovitis". PM&R KnowledgeNow. 28 February 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- Andréu JL, Otón T, Silva-Fernández L, Sanz J (February 2011). "Hand pain other than carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS): the role of occupational factors". Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 25 (1): 31–42. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2010.12.001. PMID 21663848.

- O'Neill, Carina J (2008). "de Quervain Tenosynovitis". In Frontera, Walter R; Siver, Julie K; Rizzo, Thomas D (eds.). Essentials of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Musculoskeletal Disorders, Pain, and Rehabilitation. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 129–132. ISBN 978-1-4160-4007-1. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- Stahl, Stéphane; Vida, Daniel; Meisner, Christoph; Lotter, Oliver; Rothenberger, Jens; Schaller, Hans-Eberhard; Stahl, Adelana Santos (December 2013). "Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Work-Related Cause of de Quervain Tenosynovitis". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 132 (6): 1479–1491. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000434409.32594.1b. PMID 24005369. S2CID 3430073.

- Petit Le Manac'h A, Roquelaure Y, Ha C, Bodin J, Meyer G, Bigot F, Veaudor M, Descatha A, Goldberg M, Imbernon E (September 2011). "Risk factors for de Quervain's disease in a French working population". Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 37 (5): 394–401. doi:10.5271/sjweh.3160. PMID 21431276.

- van Tulder M, Malmivaara A, Koes B (May 2007). "Repetitive strain injury". Lancet. 369 (9575): 1815–22. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60820-4. PMID 17531890. S2CID 1584416.

- Allen, Scott D; Katarincic, Julia A; Weiss, Arnold-Peter C (2004). "Common Disorders of the Hand and Wrist". In Leppert, Phyllis Carolyn; Peipert, Jeffrey F (eds.). Primary Care for Women. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 664. ISBN 978-0-7817-3790-6. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- "DE Quervain's Tenosynovitis". ASSH. American Society for Surgery of the Hand.

- Clarke MT, Lyall HA, Grant JW, Matthewson MH (December 1998). "The histopathology of de Quervain's disease". J Hand Surg Br. 23 (6): 732–4. doi:10.1016/S0266-7681(98)80085-5. PMID 9888670. S2CID 40730755.

- Read HS, Hooper G, Davie R (February 2000). "Histological appearances in post-partum de Quervain's disease". J Hand Surg Br. 25 (1): 70–2. doi:10.1054/jhsb.1999.0308. PMID 10763729. S2CID 39874610.

- Mayo Clinic. "Arm pain: Causes".

- Ashraf, MO; Devadoss, VG (22 January 2013). "Systematic review and meta-analysis on steroid injection therapy for de Quervain's tenosynovitis in adults". European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology: Orthopedie Traumatologie. 24 (2): 149–57. doi:10.1007/s00590-012-1164-z. PMID 23412309. S2CID 1393761.

- , Ilyas A, Kalbian I. De Quervain's Release. J Med Ins. 2017;2017(206.3) doi:https://jomi.com/article/206.3

- Peters-Veluthamaningal, C; van der Windt, DA; Winters, JC; Meyboom-de Jong, B (8 July 2009). "Corticosteroid injection for de Quervain's tenosynovitis" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD005616. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005616.pub2. hdl:11370/1b8025f6-66a0-44f0-9fef-7eed7c57145c. PMID 19588376.

- Coldham, F (2006). "The use of splinting in the non-surgical treatment of De Quervains disease: a review of the literature". British Journal of Hand Therapy. 11 (2): 48–55. doi:10.1177/175899830601100203. S2CID 74206208. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- Weiss AP, Akelman E, Tabatabai M (July 1994). "Treatment of de Quervain's disease". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 19 (4): 595–8. doi:10.1016/0363-5023(94)90262-3. PMID 7963313.

- Patel KR, Tadisina KK, Gonzalez MH (2013). "De Quervain's Disease". ePlasty. 13: ic52. PMC 3723064. PMID 23943679.

- Christie B. G. B. (June 1955). "Local hydrocortisone in de Quervain's disease". Br Med J. 1 (4929): 1501–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4929.1501. PMC 2062331. PMID 14378608.

- Piver JD, Raney RB (March 1952). "De Quervain's tendovaginitis". Am J Surg. 83 (5): 691–4. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(52)90304-8. PMID 14914998.

- Lamphier TA, Long NG, Dennehy T (December 1953). "De Quervain's disease: an analysis of 52 cases". Ann Surg. 138 (6): 832–41. doi:10.1097/00000658-195312000-00002. PMC 1609322. PMID 13105228.

- McKenzie JM (December 1972). "Conservative treatment of de Quervain's disease". Br Med J. 4 (5841): 659–60. doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5841.659. PMC 1786979. PMID 4645899.

- Ahuja NK, Chung KC (2004). "Fritz de Quervain, MD (1868-1940): stenosing tendovaginitis at the radial styloid process". J Hand Surg Am. 29 (6): 1164–70. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.05.019. PMID 15576233.

- Archived 21 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Nett MP, Collins MS, Sperling JW (2008). "Magnetic resonance imaging of acute "wiiitis" of the upper extremity". Skeletal Radiology. 37 (5): 481–83. doi:10.1007/s00256-008-0456-1. PMID 18259743. S2CID 9806901.

- Koh TH (December 2000). "Ulcerative "nintendinitis": a new kind of repetitive strain injury". The Medical Journal of Australia. 173 (11–12): 671. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb139392.x. PMID 11379534. S2CID 8360438.

- Rush University Medical Center (1 August 2012). "'Texting thumb' and other tech-related pain, explained". Rush University Medical Center. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- Karim SA (March 2009). "From 'playstation thumb' to 'cellphone thumb': the new epidemic in teenagers". South African Medical Journal. 99 (3): 161–2. PMID 19563092.

- Mayo Clinic Staff (1 August 2012). "De Quervain's Tenosynovitis". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- Joyce, Amy (23 April 2005). "For Some, Thumb Pain Is BlackBerry's Stain". The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "The Agony of 'BlackBerry Thumb'". Wired.com. 21 October 2005. Archived from the original on 19 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- "BlackBerry Thumb: Real Illness or Just Dumb?". Arthritis.webmd.com. 26 January 2005. Retrieved 18 May 2010.