Infibulation

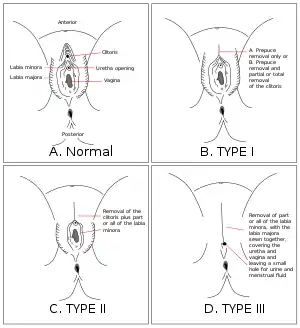

Infibulation is the ritual removal of the external female genitalia and the suturing of the vulva, a practice found mainly in northeastern Africa, particularly in Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan.[1] The World Health Organization refers to the procedure as Type III female genital mutilation. Infibulation can also refer to placing a clasp through the foreskin in men.

| Part of a series on |

| Violence against women |

|---|

| Killing |

|

| Sexual assault and rape |

|

| Disfigurement |

|

| Other issues |

|

| International legal framework |

|

| Related topics |

|

Female

Female infibulation, known as Type III FGM, and in countries in which it is practiced as pharaonic circumcision, is the removal of the inner and outer labia and the suturing of the vulva. It is usually accompanied by the removal of the clitoral glans.[2][3] The practice is concentrated in Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan.[1] During a 2014 survey in Sudan, over 80 percent of those who had experienced any form of FGM had been sewn closed.[4]

The procedure leaves a wall of skin and flesh across the vagina and the rest of the pubic area. By inserting a twig or similar object before the wound heals, a small hole is created for the passage of urine and menstrual blood. The legs are bound together for two to four weeks to allow healing.[5][6]

The vagina is usually penetrated at the time of a woman's marriage by her husband's penis, or by cutting the tissue with a knife. The vagina is opened further for childbirth and usually closed again afterwards, a process known as defibulation (or deinfibulation) and reinfibulation. Infibulation can cause chronic pain and infection, organ damage, prolonged micturition, urinary incontinence, inability to get pregnant, difficulty giving birth, obstetric fistula, and fatal bleeding.[5]

Male

Infibulation also referred to placing a clasp through the male foreskin.[7] In ancient Greece, male athletes, singers and other public performers used a clasp or string to close the foreskin and draw the penis over to one side, a practice known as kynodesmē (literally "dog tie").[8] Many kynodesmē are depicted on vases, almost exclusively confined to symposiasts and komasts, who are as a general rule older (or at least mature) men.[9] In Rome, a fibula was often a type of ring used similarly to a kynodesme.

Kynodesmē was seen as a sign of restraint and abstinence, but was also related to concerns of modesty; in artistic representations, it was regarded as obscene and offensive to show a long penis and the glans penis in particular.[8] Tying up the penis with a string was a way of avoiding what was seen as the shameful and dishonorable spectacle of an exposed glans penis, something associated with those without repute, such as slaves and barbarians. It therefore conveyed the moral worth and modesty of the subject.[9]

References

- Yoder, P. Stanley; Khan, Shane (March 2008). "Numbers of women circumcised in Africa: The Production of a Total" (PDF) (39). USAID, DHS Working Papers: 13–14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - El Dareer, Asma (1982). Woman, Why Do You Weep: Circumcision and its Consequences. London: Zed Books. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0862320997.

- For "pharaonic circumcision", also see Gruenbaum, Ellen (2001). The Female Circumcision Controversy: An Anthropological Perspective. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 43–45.

- "Sudan Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2014". UNICEF. 2014. p. 214, Table CP.10.

- Abdulcadira, Jasmine, et al. (January 2011). "Care of women with female genital mutilation/cutting". Swiss Medical Weekly, 6(14). PMID 21213149

- Momoh, Comfort (2005). "Female genital mutilation" in Comfort Momoh (ed.). Female Genital Mutilation. Radcliffe Publishing. p. 7.

- Favazza, Armando R. (1996).Bodies Under Siege: Self-mutilation and Body Modification in Culture and Psychiatry. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 190–191.

- Schmidt, Michael (2004). The First Poets. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 263.

- Zanker, Paul and Shapiro, Alan (1996). The Mask of Socrates: The Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity. University of California Press. pp. 28–29.

Further reading

- Ali, Ayaan Hirsi. Infidel: My Life, Free Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7432-8968-9

- Pieters, Guy and Lowenfels, Albert B. "Infibulation in the Horn of Africa", New York State Journal of Medicine, 77(6), April 1977, pp. 729–731.

- Whitehorn, James, Oyedeji Ayonrinde, and Samantha Maingay. "Female Genital Mutilation: Cultural and Psychological Implications," Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 17.2 (2002), pp. 161–170.