Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

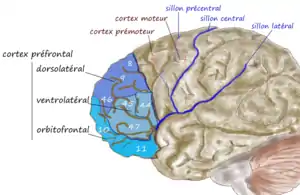

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC or DL-PFC) is an area in the prefrontal cortex of the primate brain. It is one of the most recently derived parts of the human brain. It undergoes a prolonged period of maturation which lasts until adulthood.[1] The DLPFC is not an anatomical structure, but rather a functional one. It lies in the middle frontal gyrus of humans (i.e., lateral part of Brodmann's area (BA) 9 and 46[2]). In macaque monkeys, it is around the principal sulcus (i.e., in Brodmann's area 46[3][4][5]). Other sources consider that DLPFC is attributed anatomically to BA 9 and 46[6] and BA 8, 9 and 10.[1]

| Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | |

|---|---|

An illustration of brain's prefrontal region | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Cortex praefrontalis dorsolateralis |

| MeSH | D000087643 |

| FMA | 276189 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The DLPFC has connections with the orbitofrontal cortex, as well as the thalamus, parts of the basal ganglia (specifically, the dorsal caudate nucleus), the hippocampus, and primary and secondary association areas of neocortex (including posterior temporal, parietal, and occipital areas).[7][8] The DLPFC is also the end point for the dorsal pathway (stream),[9] which is concerned with how to interact with stimuli.

An important function of the DLPFC is the executive functions, such as working memory, cognitive flexibility,[10] planning, inhibition, and abstract reasoning.[11] However, the DLPFC is not exclusively responsible for executive functions. All complex mental activity requires the additional cortical and subcortical circuits with which the DLPFC is connected.[12] The DLPFC is also the highest cortical area that is involved in motor planning, organization and regulation.[12]

Structure

As the DLPFC is composed of spatial selective neurons, it has a neural circuitry that encompasses the entire range of sub-functions necessary to carry out an integrated response, such as: sensory input, retention in short-term memory, and motor signaling.[13] Historically, the DLPFC was defined by its connection to: the superior temporal cortex, the posterior parietal cortex, the anterior and posterior cingulate, the premotor cortex, the retrosplenial cortex, and the neocerebellum.[1] These connections allow the DLPFC to regulate the activity of those regions, as well as to receive information from and be regulated by those regions.[1]

Function

Primary functions

The DLPFC is known for its involvement in the executive functions, which is an umbrella term for the management of cognitive processes,[14] including working memory, cognitive flexibility,[15] and planning.[16] A couple of tasks have been very prominent in the research on the DLPFC, such as the A-not-B task, the delayed response task and object retrieval tasks.[1] The behavioral task that is most strongly linked to DLPFC is the combined A-not-B/delayed response task, in which the subject has to find a hidden object after a certain delay. This task requires holding information in mind (working memory), which is believed to be one of the functions of DLPFC.[1] The importance of DLPFC for working memory was strengthened by studies with adult macaques. Lesions that destroyed DLPFC disrupted the macaques' performance of the A-not-B/delayed response task, whereas lesions to other brain parts did not impair their performance on this task.[1]

DLPFC is not required for the memory of a single item. Thus, damage to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex does not impair recognition memory.[17] Nevertheless, if two items must be compared from memory, the involvement of DLPFC is required. People with damaged DLPFC are not able to identify a picture they had seen, after some time, when given the opportunity to choose from two pictures.[17] Moreover, these subjects also failed in Wisconsin Card-Sorting Test as they lose track of the currently correct rule and persistently organize their cards in the previously correct rule.[18] In addition, as DLPFC deals with waking thought and reality testing, it is not active when one is asleep.[18] Likewise, DLPFC is most frequently related to the dysfunction of drive, attention and motivation.[19] Patients with minor DLPFC damage display disinterest in their surroundings and are deprived of spontaneity in language as well as behavior.[19] Patients may also be less alert than normal to people and events they know.[19] Damage to this region in a person also leads to the lack of motivation to do things for themselves and/or for others.[19]

Decision making

The DLPFC is involved in both risky and moral decision making; when individuals have to make moral decisions like how to distribute limited resources, the DLPFC is activated.[20] This region is also active when costs and benefits of alternative choices are of interest.[21] Similarly, when options for choosing alternatives are present, the DLPFC evokes a preference towards the most equitable option and suppresses the temptation to maximize personal gain.[22]

Working memory

Working memory is the system that actively holds multiple pieces of transitory information in the mind, where they can be manipulated. The DLPFC is important for working memory;[23] reduced activity in this area correlates to poor performance on working memory tasks.[24] However, other areas of the brain are involved in working memory as well.[25]

There is an ongoing discussion if the DLPFC is specialized in a certain type of working memory, namely computational mechanisms for monitoring and manipulating items, or if it has a certain content, namely visuospatial information, which makes it possible to mentally represent coordinates within the spatial domain.[23]

There have also been some suggestions that the function of the DLPFC in verbal and spatial working memory is lateralised into the left and right hemisphere, respectively. Smith, Jonides and Koeppe (1996)[26] observed a lateralisation of DLPFC activations during verbal and visual working memory. Verbal working memory tasks mainly activated the left DLPFC and visual working memory tasks mainly activated the right DLPFC. Murphy et al. (1998)[27] also found that verbal working memory tasks activated the right and left DLPFC, whereas spatial working memory tasks predominantly activated the left DLPFC. Reuter-Lorenz et al. (2000)[28] found that activations of the DLPFC showed prominent lateralisation of verbal and spatial working memory in young adults, whereas in older adults this lateralisation was less noticeable. It was proposed that this reduction in lateralisation could be due to recruitment of neurons from the opposite hemisphere to compensate for neuronal decline with ageing.

Secondary functions

The DLPFC may also be involved in the act of deception and lying,[29] which is thought to inhibit normal tendency to truth telling. Research also suggests that using TMS on the DLPFC can impede a person's ability to lie or to tell the truth.[30]

Additionally, supporting evidence suggests that the DLPFC may also play a role in conflict-induced behavioral adjustment, for instance when an individual decides what to do when faced with conflicting rules.[31] One way in which this has been tested is through the Stroop test,[32] in which subjects are shown a name of a color printed in colored ink and then are asked to name the color of the ink as fast as possible. Conflict arises when the color of the ink does not match the name of the printed color. During this experiment, tracking of the subjects' brain activity showed a noticeable activity within the DLPFC.[32] The activation of the DLPFC correlated with the behavioral performance, which suggests that this region maintains the high demands of the task to resolve conflict, and thus in theory plays a role in taking control.[32]

DLPFC may also be associated with human intelligence. However, even when correlations are found between the DLPFC and human intelligence, that does not mean that all human intelligence is a function of the DLPFC. In other words, this region may be attributed to general intelligence on a broader scale as well as very specific roles, but not all roles. For example, using imaging studies like PET and fMRI indicate DLPFC involvement in deductive, syllogistic reasoning.[33] Specifically, when involved in activities that require syllogistic reasoning, left DLPFC areas are especially and consistently active.[33]

The DLPFC may also be involved in threat-induced anxiety.[34] In one experiment, participants were asked to rate themselves as behaviorally inhibited or not. Those who rated themselves as behaviorally inhibited, moreover, showed greater tonic (resting) activity in the right-posterior DLPFC.[34] Such activity is able to be seen through Electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings. Individuals who are behaviorally inhibited are more likely to experience feelings of stress and anxiety when faced with a particularly threatening situation.[34] In one theory, anxiety susceptibility may increase as a result of present vigilance. Evidence for this theory includes neuroimaging studies that demonstrate DLPFC activity when an individual experiences vigilance.[34] More specifically, it is theorized that threat-induced anxiety may also be connected to deficits in resolving problems, which leads to uncertainty.[34] When an individual experiences uncertainty, there is increased activity in the DLPFC. In other words, such activity can be traced back to threat-induced anxiety.

Social cognition

Among the prefrontal lobes, the DLPFC seems to be the one that has the least direct influence on social behavior, yet it does seem to give clarity and organization to social cognition.[11] The DLPFC seems to contribute to social functions through the operation of its main speciality the executive functions, for instance when handling complex social situations.[11] Social areas in which the role of the DLPFC is investigated are, amongst others, social perspective taking[8] and inferring the intentions of other people,[8] or theory of mind;[11] the suppression of selfish behavior,[8][35] and commitment in a relationship.[36]

Relation to neurotransmitters

As the DLPFC undergoes long maturational changes, one change that has been attributed to the DLPFC for making early cognitive advances is the increasing level of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the DLPFC.[1] In studies where adult macaques' dopamine receptors were blocked, it was seen that the adult macaques had deficits in the A-not-B task, as if the DFPLC was taken out altogether. A similar situation was seen when the macaques were injected with MPTP, which reduces the level of dopamine in the DLPFC.[1] Even though there have been no physiological studies about involvement of cholinergic actions in sub-cortical areas, behavioral studies indicate that the neurotransmitter acetylcholine is essential for working memory function of the DLPFC.[37]

Clinical significance

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia may be partially attributed to a lack in activity in the frontal lobe.[18] The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is especially underactive when a person has chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is also related to lack of dopamine neurotransmitter in the frontal lobe.[18] The DLPFC dysfunctions are unique among the schizophrenia patients as those that are diagnosed with depression do not tend to have the same abnormal activation in the DLPFC during working memory-related tasks.[24] Working memory is dependent upon the DLPFC's stability and functionality, thus reduced activation of the DLPFC causes schizophrenic patients to perform poorly on tasks involving working memory. The poor performance contributes to the added capacity limitations in working memory that is greater than the limits on normal patients.[38] The cognitive processes that deal heavily with the DLPFC, such as memory, attention, and higher order processing, are the functions that once distorted contribute to the illness.[24]

Depression

Along with regions of the brains such as the limbic system, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex deals heavily with major depressive disorder (MDD). The DLPFC may contribute to depression due to being involved with the disorder on an emotional level during the suppression stage.[39] While working memory tasks seem to activate the DLPFC normally,[40] its decreased grey matter volume correlates to its decreased activity. The DLPFC may also have ties to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in their functions with depression.[39] This can be attributed to how the DLPFC's cognitive functions can also involve emotions, and the VMPFC's emotional effects can also involve self-awareness or self-reflection. Damage or lesion to the DLPFC can also lead to increased expression of depression symptoms.

Stress

Exposure to severe stress may also be linked to damage in the DLPFC.[41] More specifically, acute stress has a negative impact on the higher cognitive function known as working memory (WM), which is also traced to be a function of the DLPFC.[41] In an experiment, researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to record the neural activity in healthy individuals who participated in tasks while in a stressful environment.[41] When stress successfully impacted the subjects, their neural activity showed reduced working memory related activity in the DLPFC.[41] These findings not only demonstrate the importance of the DLPFC region in relation to stress, but they also suggest that the DLPFC may play a role in other psychiatric disorders. In patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), for example, daily sessions of right dorsolateral prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) at a frequency of 10 Hz resulted in more effective therapeutic stimulation.[42]

Substance use

Substance use disorders (SUD) may correlate with dorsolateral prefrontal cortex dysfunction.[43] Those who recreationally use drugs have been shown to engage in increased risky behavior, possibly correlating with a dysfunction of the DLPFC. The executive controlling functions of the DLPFC in individuals who recreationally use drugs may have a connection that is lessen from risk factoring areas such as the anterior cingulate cortex and insula.[43] This weakened connection is even shown in healthy subjects, such as a patient who continued to make risky decisions with a disconnect between their DLPFC and insula. Lesions of the DLPFC may result in irresponsibility and freedom from inhibitions,[44] and the use of drugs can invoke the same response of willingness or inspiration to engage in the daring activity.

Alcohol

Alcohol creates deficits on the function of the prefrontal cortex.[45] As the anterior cingulate cortex works to inhibit any inappropriate behaviors through processing information to the executive network of the DLPFC,[45] as noted before this disruption in communication can lead to these actions being made. In a task known as Cambridge risk task, SUD participants have been shown to have a lower activation of their DLPFC. Specifically in a test related to alcoholism, a task called the Wheel of Fortune (WOF) had adolescents with a family history of alcoholism present lower DLPFC activation.[43] Adolescents that have had no family members with a history of alcoholism did not exhibit the same decrease of activity.

See also

- Attention versus memory in prefrontal cortex

- Attentional shift

- Brodmann area 46

- Cognitive control

- Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex

- Mesocortical pathway

- Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

- Frontoparietal network

References

- Charles A. Nelson; Monica Luciana, eds. (2001). Handbook of developmental cognitive neuroscience. Cambridge, Mass. [u.a.]: MIT Press. pp. 388–392. ISBN 978-0-262-14073-7.

- Brodmann, 1909

- Walker, 1940

- Hoshi, E. (2001). "Functional specialization within the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex: a review of anatomical and physiological studies of non-human primates". Neuroscience Research. 54 (2): 73–84. doi:10.1016/j.neures.2005.10.013. PMID 16310877. S2CID 17212229.

- Mylius, V. (2013). "Definition of DLPFC and M1 according to anatomical landmarks for navigated brain stimulation: inter-rater reliability, accuracy, and influence of gender and age". NeuroImage. 78: 224–32. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.061. PMID 23567888. S2CID 1535066.

- Cieslik, E. (2013). "Is There "One" DLPFC in Cognitive Action Control? Evidence for Heterogeneity From Co-Activation-Based Parcellation". Cerebral Cortex. 23 (11): 2677–2689. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhs256. PMC 3792742. PMID 22918987.

- Baldauf, D.; Desimone, R. (2014-04-25). "Neural Mechanisms of Object-Based Attention". Science. 344 (6182): 424–427. Bibcode:2014Sci...344..424B. doi:10.1126/science.1247003. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 24763592. S2CID 34728448.

- Moss, Simmon. "Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex". Psychlopedia. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- Takahashi, Emi; Ohki, Kenichi; Kim, Dae-Shik (2013-01-15). "Dissociation and Convergence of the Dorsal and Ventral Visual Streams in the Human Prefrontal Cortex". NeuroImage. 65: 488–498. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.002. ISSN 1053-8119. PMC 4384683. PMID 23063444.

- Kaplan, J. T.; et al. (2016). "Neural correlates of maintaining one's political beliefs in the face of counterevidence". Scientific Reports. Nature. 6: 39589. Bibcode:2016NatSR...639589K. doi:10.1038/srep39589. PMC 5180221. PMID 28008965.

- Bruce L. Miller; Jeffrey L. Cummings, eds. (2007). The Human Frontal Lobes: Functions and Disorders. The Guilford Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-1-59385-329-7.

- James B. Hale; Catherine A. Fiorello (2004). School neuropsychology: A Practitioner's Handbook. Guilford Press. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-1593850111.

- Goldman-Rakic, Patricia S. (1995). "Architecture of the Prefrontal Cortex and the Central Executive". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 769 (1): 71–83. Bibcode:1995NYASA.769...71G. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb38132.x. PMID 8595045. S2CID 40870968.

- Elliott R (2003). Executive functions and their disorders. British Medical Bulletin. (65); 49–59

- Monsell S (2003). "Task switching". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 7 (3): 134–140. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(03)00028-7. PMID 12639695. S2CID 12847511.

- Chan, R. C. K.; Shum, D.; Toulopoulou, T.; Chen, E. Y. H. (2008). "Assessment of executive functions: Review of instruments and identification of critical issues". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2. 23 (2): 201–216. doi:10.1016/j.acn.2007.08.010. PMID 18096360.

- Geraldine Dawson; Kurt W. Fischer, eds. (1994). Human behavior and the developing brain. New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 978-0898620924.

- Carter, Rita (1999). Mapping the mind. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520224612.

- Miller, Bruce L. (1999). The Human Frontal Lobes. New York, New York: The Guilford Press.

- Greene, J. D.; Sommerville, RB; Nystrom, LE; Darley, JM; Cohen, JD (2001). "An fMRI Investigation of Emotional Engagement in Moral Judgment". Science. 293 (5537): 2105–8. Bibcode:2001Sci...293.2105G. doi:10.1126/science.1062872. PMID 11557895. S2CID 1437941.

- Duncan, John; Owen, Adrian M (2000). "Common regions of the human frontal lobe recruited by diverse cognitive demands". Trends in Neurosciences. 23 (10): 475–83. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01633-7. PMID 11006464. S2CID 15268389.

- Knoch, D.; Fehr, E. (2007). "Resisting the Power of Temptations: The Right Prefrontal Cortex and Self-Control" (PDF). Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1104 (1): 123–34. Bibcode:2007NYASA1104..123K. doi:10.1196/annals.1390.004. PMID 17344543. S2CID 1745375.

- Barbey AK, Koenigs M, Grafman J (May 2013). "Dorsolateral prefrontal contributions to human working memory" (PDF). Cortex. 49 (5): 1195–1205. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2012.05.022. PMC 3495093. PMID 22789779.

- Scott E. Hemby; Sabine Bahn, eds. (2006). Functional genomics and proteomics in the clinical neurosciences. Amsterdam: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0444518538.

- Donald T. Stuss; Robert T. Knight, eds. (2002). Principles of frontal lobe function. Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195134971.

- Smith, E. E.; Jonides, J.; Koeppe, R. A. (1996). "Dissociating Verbal and Spatial Working Memory Using PET". Cerebral Cortex. 6 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1093/cercor/6.1.11. PMID 8670634.

- Murphy, D. G. M., Daly, E. M., Van Amelsvoort, T., Robertson, D., Simmons, A., & Critchley, H. D. (1998). Functional neuroanatomical dissociation of verbal, visual and spatial working memory. Schizophrenia Research.

- Reuter-Lorenz; Jonides, J.; Smith, E. E.; Hartley, A.; Miller, A.; Marshuetz, C.; Koeppe (2000). "Age differences in the frontal lateralization of verbal and spatial working memory revealed by PET". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 12 (1): 174–187. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.544.9130. doi:10.1162/089892900561814. PMID 10769314. S2CID 10138007.

- Ito, Ayahito; Abe, Nobuhito; Fujii, Toshikatsu; Hayashi, Akiko; Ueno, Aya; Mugikura, Shunji; Takahashi, Shoki; Mori, Etsuro (2012). "The contribution of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex to the preparation for deception and truth-telling". Brain Research. 1464: 43–52. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2012.05.004. PMID 22580084. S2CID 37185586.

- Karton, Inga; Bachmann, Talis (2011). "Effect of prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation on spontaneous truth-telling". Behavioural Brain Research. 225 (1): 209–14. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2011.07.028. PMID 21807030. S2CID 25457056.

- "Powerful magnets hamper our ability to lie". New Scientist. 31 August 2011.

- Mansouri, F. A.; Buckley, M. J.; Tanaka, K. (2007). "Mnemonic Function of the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex in Conflict-Induced Behavioral Adjustment". Science. 318 (5852): 987–90. Bibcode:2007Sci...318..987M. doi:10.1126/science.1146384. PMID 17962523. S2CID 31089526.

- Mansouri, Farshad A.; Tanaka, Keiji; Buckley, Mark J. (February 2009). "Conflict-induced behavioural adjustment: a clue to the executive functions of the prefrontal cortex". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 10 (2): 141–152. doi:10.1038/nrn2538. PMID 19153577. S2CID 15181627.

- Kane, Michael J.; Engle, Randall W. (2002). "The role of prefrontal cortex in working-memory capacity, executive attention, and general fluid intelligence: An individual-differences perspective". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 9 (4): 637–71. doi:10.3758/BF03196323. PMID 12613671.

- Shackman, Alexander; Brenton W. Mcmenamin; Jeffrey S. Maxwell; Lawrence L. Greischar; Richard J. Davidson (April 2009). "Right Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortical Activity and Behavioral Inhibition". Psychological Science. 20 (12): 1500–1506. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02476.x. PMC 2858783. PMID 19906125.

- Van Den Bos, W.; Van Dijk, E.; Westenberg, M.; Rombouts, S. A. R. B.; Crone, E. A. (2010). "Changing Brains, Changing Perspectives: The Neurocognitive Development of Reciprocity". Psychological Science. 22 (1): 60–70. doi:10.1177/0956797610391102. PMID 21164174. S2CID 5026096.

- Petrican, Raluca; Schimmack, Ulrich (2008). "The role of dorsolateral prefrontal function in relationship commitment". Journal of Research in Personality. 42 (4): 1130–5. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.03.001.

- Yang, Yang; Paspalas, Constantinos D.; Jin, Lu E.; Picciotto, Marina R.; Arnsten, Amy F. T.; Wang, Min (2013). "Nicotinic α7 receptors enhance NMDA cognitive circuits in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (29): 12078–83. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11012078Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1307849110. PMC 3718126. PMID 23818597.

- Callicott, Joseph H. (2000). "Physiological Dysfunction of the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex in Schizophrenia Revisited". Cerebral Cortex. 10 (11): 1078–92. doi:10.1093/cercor/10.11.1078. PMID 11053229.

- Koenigs, Michael, Grafmanb, Jordan (2009). "The functional neuroanatomy of depression: Distinct roles for ventromedial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex". Behavioural Brain Research. 201 (2): 239–243. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2009.03.004. PMC 2680780. PMID 19428640.

- Cite error: The named reference Functional_Genomics was invoked but never defined

- Qin, Shaozheng; Hermans, Erno J.; Van Marle, Hein J.F.; Luo, Jing; Fernández, Guillén (2009). "Acute Psychological Stress Reduces Working Memory-Related Activity in the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex". Biological Psychiatry. 66 (1): 25–32. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.03.006. PMID 19403118. S2CID 22601360.

- Cohen, H.; Kaplan, Z; Kotler, M; Kouperman, I; Moisa, R; Grisaru, N (2004). "Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Right Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study". American Journal of Psychiatry. 161 (3): 515–24. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.515. PMID 14992978.

- Gowin, Joshua L., Mackey, Scott, Paulus, Martin P. (2013). "Altered risk-related processing in substance users: Imbalance of pain and gain". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 132 (1–2): 13–21. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.019. PMC 3748224. PMID 23623507.

- K.H. Pribram; A.R. Luria, eds. (1973). Psychophysiology of the frontal lobes. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0125643405.

- Abernathy, Kenneth, Chandler, L. Judson, Wooward, John J. (2010). "Alcohol and the Prefrontal Cortex". Functional Plasticity and Genetic Variation: Insights into the Neurobiology of Alcoholism. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. International Review of Neurobiology. Vol. 91. pp. 289–320. doi:10.1016/S0074-7742(10)91009-X. ISBN 9780123812766. PMC 3593065. PMID 20813246.