Endoscopy

An endoscopy (looking inside) is a procedure used in medicine to look inside the body.[1] The endoscopy procedure uses an endoscope to examine the interior of a hollow organ or cavity of the body. Unlike many other medical imaging techniques, endoscopes are inserted directly into the organ.

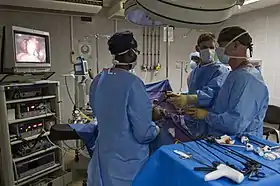

| Endoscopy | |

|---|---|

An example of an endoscopic procedure | |

| MeSH | D004724 |

| OPS-301 code | 1-40...1-49, 1-61...1-69 |

| MedlinePlus | 003338 |

There are many types of endoscopies. Depending on the site in the body and type of procedure, an endoscopy may be performed by either a doctor or a surgeon. A patient may be fully conscious or anaesthetised during the procedure. Most often, the term endoscopy is used to refer to an examination of the upper part of the gastrointestinal tract, known as an esophagogastroduodenoscopy.[2]

For nonmedical use, similar instruments are called borescopes.

History

Adolf Kussmaul was fascinated by sword swallowers who would insert a sword down their throat without gagging. This drew inspiration to insert a camera, the next problem to solve was how to insert a source of light, as they were still relying on candles and oil lamps.[3]

The term endoscope was first used on February 7, 1855, by engineer-optician Charles Chevalier, in reference to the uréthroscope of Désormeaux, who himself began using the former term a month later.[4] The self-illuminated endoscope was developed at Glasgow Royal Infirmary in Scotland (one of the first hospitals to have mains electricity) in 1894/5 by Dr John Macintyre as part of his specialization in the investigation of the larynx.[5]

Medical uses

Endoscopy may be used to investigate symptoms in the digestive system including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, difficulty swallowing, and gastrointestinal bleeding.[6] It is also used in diagnosis, most commonly by performing a biopsy to check for conditions such as anemia, bleeding, inflammation, and cancers of the digestive system.[6] The procedure may also be used for treatment such as cauterization of a bleeding vessel, widening a narrow esophagus, clipping off a polyp or removing a foreign object.[6]

Specialty professional organizations that specialize in digestive problems advise that many patients with Barrett's esophagus receive endoscopies too frequently.[7] Such societies recommend that patients with Barrett's esophagus and no cancer symptoms after two biopsies receive biopsies as indicated and no more often than the recommended rate.[8][9]

Applications

Health care providers can use endoscopy to review any of the following body parts:

- The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract):

- oesophagus, stomach and duodenum (esophagogastroduodenoscopy)

Esophageal Bougie Dilator

Esophageal Bougie Dilator - small intestine (enteroscopy)

- large intestine/colon (colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy)

- Magnification endoscopy

- bile duct

- endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), duodenoscope-assisted cholangiopancreatoscopy, intraoperative cholangioscopy

- rectum (rectoscopy) and anus (anoscopy), both also referred to as (proctoscopy)

- The respiratory tract

- The nose (rhinoscopy)

- The upper respiratory tract (laryngoscopy)

- The lower respiratory tract (bronchoscopy)

- The ear (otoscope)

- The urinary tract (cystoscopy)

- The female reproductive system (gynoscopy)

- The cervix (colposcopy)

- The uterus (hysteroscopy)

- The fallopian tubes (falloposcopy)

- Normally closed body cavities (through a small incision):

- The abdominal or pelvic cavity (laparoscopy)

- The interior of a joint (arthroscopy)

- Organs of the chest (thoracoscopy and mediastinoscopy)

Endoscopy is used for many procedures:

- During pregnancy

- Plastic surgery

- Panendoscopy (or triple endoscopy)

- Combines laryngoscopy, esophagoscopy, and bronchoscopy

- Orthopedic surgery

- Hand surgery, such as endoscopic carpal tunnel release

- Knee surgery, such as anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- Epidural space (Epiduroscopy)

- Bursae (Bursectomy)

- Endodontic surgery

- Maxillary sinus surgery

- Apicoectomy

- Endoscopic endonasal surgery

- Endoscopic spinal surgery

An endoscopy is a simple procedure that allows a doctor to look inside human bodies using an instrument called an endoscope. A cutting tool can be attached to the end of the endoscope, and the apparatus can then be used to perform minor procedures such as tissue biopsies, banding of oesophageal varices or removal of polyps.

Application in other fields

- For non-medical use, such as internal inspection of complex technical systems, borescopes are used. These are similar to endoscopes.

- The planning and architectural community use architectural endoscopy for pre-visualization of scale models of proposed buildings and cities

- Endoscopes are also a tool helpful in the examination of improvised explosive devices by bomb disposal personnel.

- Law enforcement uses endoscopes for conducting surveillance via tight spaces.

Risks

The main risks are infection, over-sedation, perforation, or a tear of the stomach or esophagus lining and bleeding.[10] Although perforation generally requires surgery, certain cases may be treated with antibiotics and intravenous fluids. Bleeding may occur at the site of a biopsy or polyp removal. Such typically minor bleeding may simply stop on its own or be controlled by cauterisation. Seldom does surgery become necessary. Perforation and bleeding are rare during gastroscopy. Other minor risks include drug reactions and complications related to other diseases the patient may have. Consequently, patients should inform their doctor of all allergic tendencies and medical problems. Occasionally, the site of the sedative injection may become inflamed and tender for a short time. This is usually not serious and warm compresses for a few days are usually helpful. While any of these complications may possibly occur, each of them occurs quite infrequently. A doctor can further discuss risks with the patient with regard to the particular need for gastroscopy.

After the endoscopy

After the procedure, the patient will be observed and monitored by a qualified individual in the endoscopy room, or a recovery area, until a significant portion of the medication has worn off. Occasionally the patient is left with a mild sore throat, which may respond to saline gargles, or chamomile tea. It may last for weeks or not happen at all. The patient may have a feeling of distention from the insufflated air that was used during the procedure. Both problems are mild and fleeting. When fully recovered, the patient will be instructed when to resume their usual diet (probably within a few hours) and will be allowed to be taken home. Where sedation has been used, most facilities mandate that the patient be taken home by another person and that they not drive or handle machinery for the remainder of the day. Patients who have had an endoscopy without sedation are able to leave unassisted.

See also

References

- "Endoscopy". British Medical Association Complete Family Health Encyclopedia. Dorling Kindersley Limited. 1990.

- "Endoscopy". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "The pioneers of endoscopy and the sword swallowers".

- Janssen, Diederik F (2021-05-17). "Who named and built the Désormeaux endoscope? The case of unacknowledged opticians Charles and Arthur Chevalier". Journal of Medical Biography. 29 (3): 176–179. doi:10.1177/09677720211018975. ISSN 0967-7720. PMID 33998906. S2CID 234747817.

- "The Scottish Society of the History of Medicine" (PDF).

- Staff (2012). "Upper endoscopy". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- American Gastroenterological Association, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Gastroenterological Association, archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2012, retrieved August 17, 2012

- Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF, Inadomi JM, Shaheen NJ (March 2011). "American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett's esophagus". Gastroenterology. 140 (3): 1084–91. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.030. PMID 21376940.

- Wang KK, Sampliner RE (March 2008). "Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett's esophagus". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 103 (3): 788–97. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01835.x. PMID 18341497. S2CID 8443847.

- "Endoscopy". NHS Choices. NHS Gov.UK. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

External links

- The Atlas of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy endoatlas.com

- El Salvador Atlas of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

- Gastrolab: Site in English, Swedish and Finnish with gastrointestinal endoscopy photolibrary Archived 2020-07-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Preventing cross-contamination from flexible endoscopes massdevice.com

- Advances in Endoscopy Archived 2018-05-13 at the Wayback Machine advancedimagingpro.com