Dental floss

Dental floss is a cord of thin filaments used in interdental cleaning to remove food and dental plaque from between teeth or places a toothbrush has difficulty reaching or is unable to reach.[1] Its regular use as part of oral cleaning is designed to maintain oral health.

Use of floss is recommended to prevent gingivitis and the build-up of plaque.[2] The American Dental Association claims that up to 80% of plaque can be removed by flossing, and it may confer a particular benefit in individuals with orthodontic devices.[3] However, empirical scientific evidence demonstrating the clinical benefit of flossing as an adjunct to routine tooth brushing alone remains limited.[3]

A Japanese macaque and long-tailed macaques have been observed in the wild and in captivity flossing with human hair and feathers.[4][5][6]

History

.jpg.webp)

Levi Spear Parmly, a dentist from New Orleans, is credited with inventing the first form of dental floss.[7] In 1819, he recommended running a waxen silk thread "through the interstices of the teeth, between their necks and the arches of the gum, to dislodge that irritating matter which no brush can remove and which is the real source of disease."[8][9] He considered this the most important part of oral care.[7] Floss was not commercially available until 1882, when the Codman and Shurtleft company started producing unwaxed silk floss.[10] In 1898, the Johnson & Johnson Corporation received the first patent for dental floss that was made from the same silk material used by doctors for silk stitches.[10]

One of the earliest depictions of the use of dental floss in literary fiction is found in James Joyce's famous novel Ulysses (serialized 1918–1920), but the adoption of floss was low before World War II. During the war, nylon floss was developed by physician Charles C. Bass.[10] Nylon floss was found to be better than silk because of its greater abrasion resistance and ability to be produced in great lengths and at various sizes.[10]

Floss became part of American and Canadian daily personal dental care routines in the 1970s.[11]

Use

Dental professionals recommend that a person floss once per day before or after brushing to reach the areas that the brush will not and allow the fluoride from the toothpaste to reach between the teeth.[12][13] Floss is commonly supplied in plastic dispensers that contain 10 to 100 meters of floss. After pulling out approximately 40 cm of floss, the user pulls it against a blade in the dispenser to cut it off. The user then strings the piece of floss on a fork-like instrument or holds it between their fingers using both hands with about 1–2 cm of floss exposed. The user guides the floss between each pair of teeth and gently curves it against the side of the tooth in a 'C' shape and guides it under the gumline. This removes particles of food stuck between teeth and dental plaque that adhere to dental surfaces below the gumline.[3]

Types

A variety of dental flosses are commonly available. Floss is available in many forms including waxed, unwaxed monofilaments and multifilaments. Dental floss that is made of monofilaments coated in wax slides easily between teeth, does not fray and is generally higher in cost than its uncoated counterparts. The most important difference between available dental flosses is thickness. Waxed and unwaxed floss are available in varying widths. Studies have shown that there is no difference in the effectiveness of waxed and unwaxed dental floss,[14] but some waxed types of dental floss are said to contain antibacterial agents and/or sodium fluoride. Factors to consider in choosing a floss include the amount of space between teeth and user preference. Dental tape is a type of floss that is wider and flatter than conventional floss. Dental tape is recommended for people with larger tooth surface area.[14]

The ability of different types of dental floss to remove dental plaque does not vary significantly;[15] the least expensive floss has essentially the same impact on oral hygiene as the most expensive.

Factors to be considered when choosing the right floss or whether the use of floss as an interdental cleaning device is appropriate may be based on:[14]

- The tightness of the contact area: determines the width of floss

- The contour of the gingival tissue

- The roughness of the interproximal surface

- The user's manual dexterity and preference: to determine if a supplemental device is required

Specialized plastic wands, or floss picks, have been produced to hold the floss. These may be attached to or separate from a floss dispenser. While wands do not pinch fingers like regular floss can, using a wand may be awkward and can also make it difficult to floss at all the angles possible with regular floss. These types of flossers also run the risk of missing the area under the gum line that needs to be flossed. On the other hand, the enhanced reach of a wand can make flossing the back teeth easier.

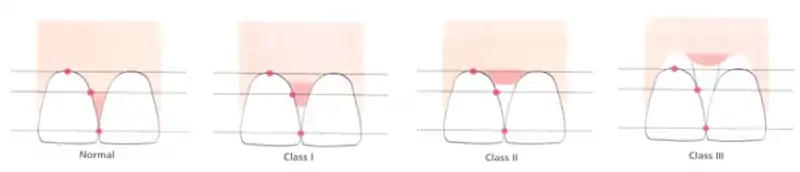

Dental floss is the most frequently recommended cleaning aid for teeth sides with a normal gingiva contour in which the spaces between teeth are tight and small.[14] The dental term ‘embrasure space’ describes the size of the triangular-shaped space immediately under the contact point of two teeth.[14] The size of the embrasure space is useful in selecting the most appropriate interdental cleaning aid. There are three interproximal embrasure types or classes as described below:[14]

- Type I – the gums fills embrasure space completely

- Type II – the gums partially fills embrasure space

- Type III – the gums do not fill embrasure space

The table below describes the types of interdental non-powered self-care products available.[14]

| Interdental nonpowered self-care products | Description | Indications | Contraindications and limitations | Common problems experienced during misuse of product | Number of times it can be used/duration of use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waxed floss | Traditional string floss, Nylon waxed Monofilament floss also available coated in polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), Does not fray | Type I embrasures, Floss cleans between the gum and tooth | Type II and III embrasures | Floss cuts, Floss clefts, Circulation to fingers may cut off from wrapping floss too tight, Inability to reach back teeth due to manual dexterity problems | One time use. Dispose after use |

| Unwaxed floss | Traditional string floss, Unwaxed, multifilaments | Type I embrasures, Floss cleans between the gum and tooth | Type II and III embrasures | See waxed floss | One time use. Dispose after use |

| Dental tape | Waxed floss that has a wider and flatter design to conventional floss | Type I embrasures, Floss cleans between the gum and tooth that may have large tooth surface area | Type II and III embrasures | See waxed floss | One time use. Dispose after use |

| Tufted/braided dental floss/ Superfloss | Regular diameter floss, wider tufted portion looks like yarn. Tip of product also resembles a threader | Type II and III embrasures. Under pontics of fixed partial dentures | Type I embrasures | Trauma from forcing threader into tissues. Yarnlike portion/fibers may catch on appliances or dental work (which may cause gum irritation/problem) | One time use. Dispose after use |

| Floss holder | Handle with two prongs in Y or F shape | Type I embrasures. Recommended for individuals that lack manual dexterity, who are physically challenged, or who have a strong gag reflex. Floss holders may assist caregivers | Type II and III embrasures | Unable to maintain tension of floss against tooth and fully wrap around tooth side. Need to set a fulcrum/finger rest (e.g. cheek, chin) to avoid trauma to gums and floss cuts | Can be used a number of times, however floss is to be changed after each use |

| Floss threader | A nylon loop designed to resemble a needle with large opening to thread floss. Tip of floss threader inserted and pulled through the space between two teeth to allow cleaning of the teeth sides | Type I embrasures: tight contacts between teeth, floss between and under abutment teeth and pontics of fixed prosthesis (e.g. fixed bridges and dental implants), under orthodontic appliances such as wires and lingual bar, under bars for implants | Type II and III embrasures | Trauma to gums from flossing threader into tissues | Can be used a number of times, however floss is to be changed after each use |

| Threader-tip floss | A length of floss with an attached threader tip | Type I embrasures, Floss cleans between the gum and tooth | Type II and III embrasures | See waxed floss | One time use. Dispose after use |

The table below describes the different types of Interdental powered self-care products available.[14]

| Interdental powered self-care products | Description | Indications | Contraindications and limitations | Common problems experienced during misuse of product |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power flossers | Bow type tip and single filament nylon tip | Type I embrasures: Individuals with physical challenges. Individuals who cannot master traditional string floss. Individual preference. | Type II and III embrasures. Tight contacts between teeth or crowded teeth | Floss cuts or clefts with floss holder designs. Unable to maintain tension or wrap floss completely around tooth side. |

Efficacy

Evidence

The American Dental Association has stated that flossing in combination with tooth brushing can help prevent gum disease[16] and halitosis.[17]

However, evidence favoring commonplace use of floss remains limited. A 2008 systematic review concluded that adjunct flossing was no more effective than tooth brushing alone in reducing plaque or gingivitis.[3] The authors concluded that routine instruction of flossing in gingivitis patients as helpful adjunct therapy is not supported by scientific evidence, and that flossing recommendations should be made by dental professionals on an individual basis.[3]

A 2011 Cochrane Database systematic review identified "some evidence from 12 studies that flossing in addition to tooth brushing reduces gingivitis compared to tooth brushing alone", and "weak, very unreliable evidence from 10 studies that flossing plus tooth brushing may be associated with a small reduction in plaque at 1 and 3 months."[18] Studies of flossing behavior are based on self-report and many people do not floss properly. A 2006 review of 6 studies in which professionals flossed the teeth of school children over a period of 1.7 years showed a 40% reduction in the risk of tooth decay.[19]

More recently, a 2019 Cochrane Database systematic review compared toothbrushing alone to interdental cleaning devices, and also compared flossing to other interdental cleaning methods.[20] In all, 35 randomized control trials met the criteria for inclusion, with all but 2 studies at high risk for performance bias. The authors concluded that “overall, the evidence was low to very low certainty, and the effect sizes observed may not be clinically important.”

As many authors note, the efficacy of flossing may be highly variable based on individual preference, technique, and motivation.[21] Moreover, flossing may be a relatively more difficult and tedious method of interdental cleaning compared to an interdental brush.[21]

Exclusion from US Dietary Guidelines in 2015

There was a controversy when the 2015 United States Dietary Guidelines for Americans[22] did not include a recommendation about flossing. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture publish Dietary Guidelines for Americans every five years.[23] Guidelines published in 2000, 2005 and 2010[24] recommended flossing as part of a combined approach to preventing dental diseases. The 2010 Guidelines[25] mention flossing once in 95 pages, in 2005[26] the word also appears once in 71 pages and it appears twice in the 38-page 2000 document.[27]

In August 2016, an Associated Press (AP) article titled "Medical benefits of dental floss unproven"[28] reported on the omission of flossing from the 2015 document. The article tied the omission to the AP's Freedom of Information Request to the departments of Health and Human Services and Agriculture where it asked for the scientific evidence behind the Guidelines’ flossing recommendation noting that “The guidelines must be based on scientific evidence, under the law.” The story was picked up by other news organizations including The New York Times in an article entitled "Feeling Guilty About Not Flossing? Maybe There’s No Need".[29]

The American Dental Association contacted the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services[30][31] about the omission and reported that the omission of the flossing recommendation was due to the fact that the Dietary Guidelines chose to focus on diet and that the omission was not because the Department questions the efficacy of flossing. As reported by Medscape

An HHS spokesperson explained in an e-mailed statement that "since neither the 2010 nor 2015 Advisory Committees reviewed evidence on brushing and flossing teeth, the authors of the current edition decided not to carry forward the information on brushing and flossing included in past editions of the guidelines. By doing so, they were not implying that this is not an important oral hygiene practice. It is also important to note that, although dental floss was mentioned in past editions of the Guidelines, it was most likely identified as a supporting recommendation along with brushing teeth, with the primary emphasis being on the nutrition-based recommendation to reduce added sugars." The 2010 guidelines mention flossing only once, as one of the components of an oral health regimen.[32]

A website managed by a maker of dental floss referred to the entire episode as "Flossgate".[33]

Floss for orthodontic appliances

Orthodontic appliances, such as brackets, wires, and bands, can harbor plaque with more virulent changes in bacterial composition, which can ultimately cause a reduction in periodontal health as indicated by increased gingival recession, bleeding on probing, and plaque retention measurements.[34] Furthermore, fixed appliances makes plaque control more challenging and restricts the natural cleaning action of the tongue, lips, and cheek to remove food and bacterial debris from tooth surfaces, and also creates new plaque stagnation areas that stimulate the colonisation of pathogenic bacteria.[35]

Patients undergoing orthodontic treatment may be recommended to maintain a high level of plaque control through not only conscientious toothbrushing, but also proximal surface cleaning via interdental aids, with dental floss being the most recommended by dental professionals.[34] Notably, small-scale clinical studies have demonstrated that dental floss, when used correctly, may lead to clinically significant improvements in proximal gingival health.[34]

Floss threader

A floss threader is loop of fiber that is shaped in order to produce better handling characteristics. It is (similar to fishing line) used to thread floss into small, hard to reach sites around teeth.[36] Threaders are sometimes required to floss with dental braces, fix retainers, and bridge.

Floss pick

A floss pick is a disposable oral hygiene device generally made of plastic and dental floss. The instrument is composed of two prongs extending from a thin plastic body of high-impact polystyrene material. A single piece of floss runs between the two prongs. The body of the floss pick generally tapers at its end in the shape of a toothpick. There are two types of angled floss picks in the oral care industry, the Y-shaped angle and the F-shaped angle floss pick. At the base of the arch where the "Y" begins to branch there is a handle for gripping and maneuvering before it tapers off into a pick.

Floss picks are manufactured in a variety of shapes, colors and sizes for adults and children. The floss can be coated in fluoride, flavor or wax.[37]

History of floss pick

In 1888, B.T. Mason wrapped a fibrous material around a toothpick and dubbed it the "combination tooth pick."[38] In 1916, J.P. De L'eau invented a dental floss holder between two vertical poles.[39] In 1935, F.H. Doner invented what today's consumer knows as the Y-shaped angled dental appliance.[40] In 1963, James B. Kirby invented a tooth-cleaning device that resembles an archaic version of today's F-shaped floss pick.[41]

In 1972, an inventor named Richard L. Wells found a way to attach floss to a single pick end.[42] In the same year, another inventor named Harry Selig Katz came up with a method of making a disposable dental floss tooth pick.[43]

Environmental Impact

It’s estimated that the yearly production of almost 5 billion single-use flossers for North America emits about 10,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalents per year. This results in 10 million pounds of plastic trash entering the North American environment every year.[44][45]

See also

References

- "How to Floss". Flossing Techniques-Flossing Teeth Effectively. Colgate. 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- Bauroth K, Charles CH, Mankodi SM, Simmons BS, Zhao Q, Kumar LD (2003). "The efficacy of an essential oil antiseptic mouthrinse vs. dental floss in controlling interproximal gingivitis". Journal of the American Dental Association. 134 (3): 359–365. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0167. PMID 12699051.

- Berchier CE, Slot DE, Haps S, van der Weijden GA (2008). "The efficacy of dental floss in addition to a toothbrush on plaque and parameters of gingival inflammation: a systematic review". International Journal of Dental Hygiene. 6 (4): 265–279. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00336.x. PMID 19138178.

The dental professional should determine, on an individual patient basis, whether high-quality flossing is an achievable goal. In light of the results of this comprehensive literature search and critical analysis, it is concluded that a routine instruction to use floss is not supported by scientific evidence.

- "Monkeys 'teach infants to floss'". BBC News. 12 March 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- Jean-Baptiste Leca; Noëlle Gunst; Michael A. Huffman (10 July 2009). "The first case of dental flossing by a Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata): implications for the determinants of behavioral innovation and the constraints on social transmission". Primates. 51 (13): 13–22. doi:10.1007/s10329-009-0159-9. PMID 19590935. S2CID 35199618. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- "Monkey seen 'flossing' after eating". MSN. 21 September 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- Sanoudos M, Christen AG (1999). "Levi Spear Parmly: the apostle of dental hygiene". Journal of the History of Dentistry. 47 (1): 3–6. PMID 10686903.

- Christen AG (1995). "Sumter Smith Arnim, DDS, PhD (1904-1990): a pioneer in preventive dentistry". Journal of Dental Research. 74 (10): 1630–5. doi:10.1177/00220345950740100201. PMID 7499584. S2CID 33794436.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Parmly LS (1819). A Practical Guide to the Management of the Teeth; Comprising a Discovery of the Origin of Caries, or Decay of the Teeth. Philadelphia, PA: Collins & Croft. p. 72.

- Kruszelnicki, KS (30 March 2001). "Dental Floss 1". ABC Science. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Resnick, Brian (August 2, 2016). "If you don't floss daily, you don't need to feel guilty". Vox.

- American Dental Association, "Floss and Other Interdental Cleaners Archived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine". Accessed 12 April 2010.

- "Flossing & Brushing". Canadian Dental Association. 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- Darby M, Walsh M. Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice. 3rd Ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2010. p.402-410

- Heasman P (editor) (2008). Restorative dentistry, paediatric dentistry and orthodontics (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 37. ISBN 9780443068959.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - American Dental Association, Accessed 28 November 2009. "ADA.org: ADA Seal of Acceptance: Floss and Other Interdental Cleaners". Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - American Dental Association, "Bad Breath (Halitosis)". Accessed 28 November 2009. Archived March 6, 2008.

- Sambunjak D, Nickerson JW, Poklepovic T, Johnson TM, Imai P, Tugwell P, Worthington HV (2011). "Flossing for the management of periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD008829. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008829.pub2. PMID 22161438. S2CID 70702223.

- Longbottom, Chris (2006). "Professional flossing is effective in reducing interproximal caries risk in children who have low fluoride exposures: Does dental flossing reduce interproximal caries incidence?". Evidence-Based Dentistry. 7 (3): 68. doi:10.1038/sj.ebd.6400425. ISSN 1462-0049. PMID 17003792.

- Worthington, Helen V; MacDonald, Laura; Poklepovic Pericic, Tina; Sambunjak, Dario; Johnson, Trevor M; Imai, Pauline; Clarkson, Janet E (2019-04-10). Cochrane Oral Health Group (ed.). "Home use of interdental cleaning devices, in addition to toothbrushing, for preventing and controlling periodontal diseases and dental caries". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (4): CD012018. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012018.pub2. PMC 6457073. PMID 30968949.

- Imal P.; Yu X.; MacDonald D. (2012). "Comparison of interdental brush to dental floss for reduction of clinical parameters of periodontal disease: A systematic review". Canadian Journal of Dental Hygiene. 46: 63–78.

- 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (8 ed.). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. December 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- "About the Dietary Guidelines". Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- "Previous Dietary Guidelines". Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010 (7 ed.). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. December 2010. p. 48. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005 (6 ed.). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. January 2005. p. 37. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2000 (5 ed.). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2000. p. 32. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Donn, Jeff (2 August 2016). "Medical benefits of dental floss unproven". Associated Press. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Saint Louis, Catherine (2 August 2016). "Feeling Guilty About Not Flossing? Maybe There's No Need". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Manchir, Michelle (2 August 2016). "Government, ADA recognize importance of flossing". ADA News. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- "Federal Government, ADA Emphasize Importance of Flossing and Interdental Cleaners". ADA News. 4 August 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- MacReady, Norra (5 August 2016). "Dietary Guidelines Omit Flossing, but Patients Shouldn't". Medscape Medical News. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ""Flossgate" Controversy: Changes to the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans". DentalCare.com. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Zanatta Fabricio MC, Rosing Cassiano, . Association between dental floss use and gingival conditions in orthodontic patients. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthpedics. 2011;140(6):812-21.

- Srivastava Kamna TT, Khanna Rohit, Sachan Kiran,. Risk factors and management of white spot lesions in orthodontics. Journal of Orthodontic Science. 2013;2(2):43-9.

- Johnson & Johnson (27 December 1977). "Dental floss threader with locking means (Patent US 4064883)". Google Patents. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- "Floss and Other Interdental Cleaners". American Dental Association. Archived from the original on 2015-12-25. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- "Patent US407362 - Combination tooth-pick - Google Patents". Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- "Dental Floss Holder". U.S. Patent. Archived from the original on 2013-01-07. Retrieved 2013-04-11.

- "Patent US2076449 - Dental instrument - Google Patents". Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- "Patent US3106216 - Tooth cleaning device - Google Patents". Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- "Patent US3775849 - Dental handpiece attachment - Google Patents". Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- "Patent US3926201 - Method of making a disposable dental floss tooth pick - Google Patents". Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- Cheprasov, Artem (August 22, 2021). "Are Floss Picks Bad for the Environment? Science Says Yes".

- Cheprasov, Artem (September 23, 2021). "Single-Use Floss Picks Worsen Global Warming".

External links

- “Medical Benefits of Dental Floss Unproven” (Aug. 2, 2016).

- Oral-B Glide dental floss may expose people to harmful chemicals Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

- Boronow, Katherine E.; Brody, Julia Green; Schaider, Laurel A.; Peaslee, Graham F.; Havas, Laurie; Cohn, Barbara A. (March 2019). "Serum concentrations of PFASs and exposure-related behaviors in African American and non-Hispanic white women". Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology. 29 (2): 206–217. doi:10.1038/s41370-018-0109-y. PMC 6380931. PMID 30622332.