Alpha defensin

Alpha defensins are a family of mammalian defensin peptides of the alpha subfamily. In mammals they are also known as cryptdins and are produced within the small bowel. Cryptdin is a portmanteau of crypt and defensin.

| Mammalian defensin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

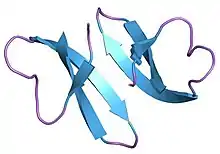

Structure of defensin HNP-3.[1] | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Defensin_1 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00323 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR006081 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00242 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1dfn / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| TCDB | 1.C.19 | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 54 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 1tv0 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Defensins are 2-6 kDa, cationic, microbicidal peptides active against many Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, fungi, and enveloped viruses,[2] containing three pairs of intramolecular disulfide bonds. On the basis of their size and pattern of disulfide bonding, mammalian defensins are classified into alpha, beta and theta categories. Alpha-defensins, which have been identified in humans, monkeys and several rodent species, are particularly abundant in neutrophils, certain macrophage populations and Paneth cells of the small intestine.

Defensins are produced constitutively and/or in response to microbial products or proinflammatory cytokines. Some defensins are also called corticostatins (CS) because they inhibit corticotropin-stimulated corticosteroid production. The mechanism(s) by which microorganisms are killed and/or inactivated by defensins is not understood completely. However, it is generally believed that killing is a consequence of disruption of the microbial membrane. The polar topology of defensins, with spatially separated charged and hydrophobic regions, allows them to insert themselves into the phospholipid membranes so that their hydrophobic regions are buried within the lipid membrane interior and their charged (mostly cationic) regions interact with anionic phospholipid head groups and water. Subsequently, some defensins can aggregate to form 'channel-like' pores; others might bind to and cover the microbial membrane in a 'carpet-like' manner. The net outcome is the disruption of membrane integrity and function, which ultimately leads to the lysis of microorganisms. Some defensins are synthesized as propeptides which may be relevant to this process. Alpha defensins of the mouse bowel were historically called cryptdins when first discovered.

Structure

HNP-1, HNP-2 and HNP-3 are encoded by two genes DEFA1 and DEFA3 localized at chromosome 8, location 8p23.1. DEFA1 and DEFA3 encode identical peptides except the conversion of the first amino acid from alanine in HNP-1 to aspartic acid in HNP-3; HNP-2 is an N-terminally truncated iso-form lacking the first amino acid. Human neutrophil peptides are found in human atherosclerotic arteries, inhibit LDL metabolism and fibrinolysis and promote Lp(a) binding.[3]

Like other alpha-defensins, cryptdins are small, 32-36 amino acid long cationic peptides. They possess 6 conserved cysteines that form a tridisulfide array with an arrangement of cysteine pairings that typify alpha-defensins. Cryptdins also display a secondary and tertiary structure that is dominated by a three-stranded beta-sheet. The topology that arises from this structure is an amphipathic globular form in which the termini are paired opposite a pole including a cluster of cationic residues.[4]

Sequences of major human α-defensins:[5]

| Gene | Aliases | Peptide | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEFA1 | HNP1 | human neutrophil peptide 1 | ACYCRIPACIAGERRYGTCIYQGRLWAFCC |

| HNP2 | human neutrophil peptide 2 | CYCRIPACIAGERRYGTCIYQGRLWAFCC | |

| DEFA3 | HNP3 | human neutrophil peptide 3 | DCYCRIPACIAGERRYGTCIYQGRLWAFCC |

| DEFA4 | HNP4 | human neutrophil peptide 4 | VCSCRLVFCRRTELRVGNCLIGGVSFTYCCTRV |

| DEFA5 | HD5 | human defensin 5 | ATCYCRHGRCATRESLSGVCEISGRLYRLCCR |

| DEFA6 | HD6 | human defensin 6 | AFTCHCRRSCYSTEYSYGTCTVMGINHRFCCL |

Genes encoding cryptdins are located on the proximal arm of mouse chromosome 8. They are similar to other enteric alpha-defensins genes in that they involve a two exon structure. The first exon encodes an N-terminal canonical signal peptide and proregion that is present in the cryptdin precursor. The processed, mature peptide is encoded by the second exon which is separated from the first exon by a ~500 bp intron.[6]

Biosynthesized as precursors possessing an anionic, N-terminal proregion, cryptdins are packaged into the apically directed secretory granules of Paneth cells. During this process and perhaps succeeding it, the precursors are cleaved by matrix metalloproteinase-7 (matrilysin; MMP-7). As a result of this proteolysis, the C-terminal mature form is released from the proregion.[7]

Functional characteristics

With the ability to kill gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, fungi, spirochetes and some enveloped viruses, cryptdins are classified as broad-spectrum antimicrobial peptides. Although it is the least expressed of the six isoforms, cryptdin-4 is the most bactericidal. Procryptdins, however, are nonbactericidal and thus require degradation of the proregion by MMP-7 for activation. In response to bacterial antigens, Paneth cells release their secretory granules into the lumen of intestinal crypts. There, cryptdins, along with other antimicrobial peptides expressed by Paneth cells, contribute to enteric mucosal innate immunity by clearing the intestinal crypt of potential invading pathogens.[8]

Human defensins

Initially human alpha defensin peptides were isolated from the neutrophils and are thus called human neutrophil peptides.[9] Human neutrophil peptides are also known as α-defensins.

Human neutrophil-derived alpha-defensins (HNPs) are capable of enhancing phagocytosis by mouse macrophages. HNP1-3 have been reported to increase the production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-1, while decreasing the production of IL-10 by monocytes. Increased levels of proinflammatory factors (e.g., IL-1, TNF, histamine and prostaglandin D2) and suppressed levels of IL-10 at the site of microbial infection are likely to amplify local inflammatory responses. This might be further reinforced by the capacity of some human and rabbit alpha-defensins to inhibit the production of immunosuppressive glucocorticoids by competing for the binding of adrenocorticotropic hormone to its receptor. Moreover, human alpha-defensins can enhance or suppress the activation of the classical pathway of complement in vitro by binding to solid-phase or fluid-phase complement C1q, respectively. The capacity of defensins to enhance phagocytosis, promote neutrophil recruitment, enhance the production of proinflammatory cytokines, suppress anti-inflammatory mediators and regulate complement activation argues that defensins upregulate innate host inflammatory defenses against microbial invasion.

Human Neutrophil Defensin-1, -3, and -4 Are Elevated in Nasal Aspirates from Children with Naturally Occurring Adenovirus Infection.[10] In one small study, a significant increase in alpha-defensin levels was detected in T cell lysates of schizophrenia patients; in discordant twin pairs, unaffected twins also had an increase, although not as high as that of their ill siblings.[11]

The Virtual Colony Count antibacterial assay was originally developed to measure the activity of all six human alpha defensins on the same microplate.[12]

In human plasma

HNPs have been extensively studied as plasma marker of a range of diseases such as atherosclerosis, rheumatic diseases,[13] infections,[14] cancer,[15] preeclampsia,[16] and schizophrenia.[17] Antibodies directed against fully processed HNP-1 seem to have low affinity for the propeptides, proHNPs. A recent study used antibodies directed against proHNPs to show that the predominant forms of alpha-defensins in plasma are in fact proHNPs.[18] ProHNPs are exclusively synthesized by neutrophil precursors in the bone marrow and appear to be very specific markers of granulopoiesis.

Gut expression

Cryptdins are the protein products of a related family of highly polymorphic genes that are specifically expressed by mouse Paneth cells at the base of intestinal crypts.[19] They were first characterized as products of cDNAs derived from mouse small intestinal RNA. To date, over 25 cryptdin-encoding transcripts have been described. Despite the expression of a relatively large number of cryptdin isoforms, only 6 cryptdins have been isolated at the protein level. Conventional nomenclature labels the isoforms cryptdins-1 through -6 in order of discovery. The primary structures of cryptdin isoforms are highly homologous. Most differences between the isoforms lie in the identity of residues at the N- and C-termini.

See also

- Defensin

- α-defensin

- β-defensin

- θ-defensin

- Cryptdin

References

- Hill CP, Yee J, Selsted ME, Eisenberg D (March 1991). "Crystal structure of defensin HNP-3, an amphiphilic dimer: mechanisms of membrane permeabilization". Science. 251 (5000): 1481–5. Bibcode:1991Sci...251.1481H. doi:10.1126/science.2006422. PMID 2006422.

- Selsted ME, White SH, Wimley WC (1995). "Structure, function, and membrane integration of defensins". Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 5 (4): 521–527. doi:10.1016/0959-440X(95)80038-7. PMID 8528769.

- Nassar H, Lavi E, Akkawi S, Bdeir K, Heyman SN, Raghunath PN, Tomaszewski J, Higazi AA (Oct 2007). "alpha-Defensin: link between inflammation and atherosclerosis". Atherosclerosis. 194 (2): 452–7. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.08.046. PMID 16989837.

- Satchell DP, Sheynis T, Shirafuji Y, Kolusheva S, Ouellette AJ, Jelinek R (2003). "Interactions of mouse Paneth cell alpha-defensins and alpha-defensin precursors with membranes. Prosegment inhibition of peptide association with biomimetic membranes". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (16): 13838–46. doi:10.1074/jbc.M212115200. PMID 12574157.

- Bowdish DM, Davidson DJ, Hancock RE (2006). "Immunomodulatory Properties of Defensins and Cathelicidins". CTMI. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 306: 27–66. doi:10.1007/3-540-29916-5_2. ISBN 978-3-540-29915-8. PMC 7121507. PMID 16909917.

- Ouellette AJ, Darmoul D, Tran D, Huttner KM, Yuan J, Selsted ME (1999). "Peptide localization and gene structure of cryptdin 4, a differentially expressed mouse paneth cell alpha-defensin". Infect. Immun. 67 (12): 6643–51. doi:10.1128/IAI.67.12.6643-6651.1999. PMC 97078. PMID 10569786.

- Wilson C, Ouellette A, Satchell D, Ayabe T, López-Boado Y, Stratman J, Hultgren S, Matrisian L, Parks W (1999). "Regulation of intestinal alpha-defensin activation by the metalloproteinase matrilysin in innate host defense". Science. 286 (5437): 113–7. doi:10.1126/science.286.5437.113. PMID 10506557.

- Ayabe T, Satchell DP, Wilson CL, Parks WC, Selsted ME, Ouellette AJ (2000). "Secretion of microbicidal alpha-defensins by intestinal Paneth cells in response to bacteria". Nat. Immunol. 1 (2): 113–8. doi:10.1038/77783. PMID 11248802. S2CID 23204633.

- Ganz T, Selsted ME, Szklarek D, Harwig SS, Daher K, Bainton DF, Lehrer RI (Oct 1985). "Defensins. Natural peptide antibiotics of human neutrophils". J Clin Invest. 76 (4): 1427–35. doi:10.1172/JCI112120. PMC 424093. PMID 2997278.

- V. S. Priyadharshini, F. Ramírez-Jiménez, M. Molina-Macip, et al., “Human Neutrophil Defensin-1, -3, and -4 Are Elevated in Nasal Aspirates from Children with Naturally Occurring Adenovirus Infection,” Canadian Respiratory Journal, vol. 2018, Article ID 1038593, 6 pages, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1038593.

- Craddock RM, Huang JT, Jackson E, et al. (March 2008). "Increased alpha defensins as a blood marker for schizophrenia susceptibility". Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 7 (7): 1204–13. doi:10.1074/mcp.M700459-MCP200. PMID 18349140.

- Ericksen B, Wu Z, Lu W, Lehrer RI (2005). "Antibacterial Activity and Specificity of the Six Human α-Defensins". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49 (1): 269–75. doi:10.1128/AAC.49.1.269-275.2005. PMC 538877. PMID 15616305.

- Vordenbäumen, S; Sander, O; Bleck, E; Schneider, M; Fischer-Betz, R (May–Jun 2012). "Cardiovascular disease and serum defensin levels in systemic lupus erythematosus". Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 30 (3): 364–70. PMID 22510487.

- Panyutich, AV; Panyutich, EA; Krapivin, VA; Baturevich, EA; Ganz, T (August 1993). "Plasma defensin concentrations are elevated in patients with septicemia or bacterial meningitis". The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 122 (2): 202–7. PMID 8340706.

- Droin, N; Hendra, JB; Ducoroy, P; Solary, E (Aug 20, 2009). "Human defensins as cancer biomarkers and antitumour molecules". Journal of Proteomics. 72 (6): 918–27. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2009.01.002. PMID 19186224.

- Prieto, JA; Panyutich, AV; Heine, RP (January 1997). "Neutrophil activation in preeclampsia. Are defensins and lactoferrin elevated in preeclamptic patients?". The Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 42 (1): 29–32. PMID 9018642.

- Craddock, RM; Huang, JT; Jackson, E; Harris, N; Torrey, EF; Herberth, M; Bahn, S (July 2008). "Increased alpha-defensins as a blood marker for schizophrenia susceptibility". Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 7 (7): 1204–13. doi:10.1074/mcp.M700459-MCP200. PMID 18349140.

- Glenthøj, A; Glenthøj, AJ; Borregaard, N (August 2013). "ProHNPs are the principal α-defensins of human plasma". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 43 (8): 836–43. doi:10.1111/eci.12114. PMID 23718714. S2CID 205092943.

- Ouellette AJ (1997). "Paneth cells and innate immunity in the crypt microenvironment". Gastroenterology. 113 (5): 1779–84. doi:10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352884. PMID 9352884.