Hemangiosarcoma

Hemangiosarcoma is a rapidly growing, highly invasive variety of cancer that occurs almost exclusively in dogs, and only rarely in cats, horses, mice,[1] or humans (vinyl chloride toxicity). It is a sarcoma arising from the lining of blood vessels; that is, blood-filled channels and spaces are commonly observed microscopically. A frequent cause of death is the rupturing of this tumor, causing the patient to rapidly bleed to death.

| Hemangiosarcoma | |

|---|---|

| |

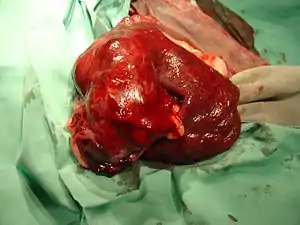

| Hemangiosarcoma of the spleen in a dog, removed after surgery | |

| Specialty | Veterinary medicine |

The term "angiosarcoma", when used without a modifier, usually refers to hemangiosarcoma.[2] However, glomangiosarcoma (8710/3) and lymphangiosarcoma (9170/3) are distinct conditions (in humans).

Dogs

Hemangiosarcoma is quite common in dogs, and more so in certain breeds including German Shepherds and Golden Retrievers.[3] It also occurs in cats, but much more rarely. Dogs with hemangiosarcoma rarely show clinical signs until the tumor has become very large and has metastasized. Typically, clinical signs are due to hypovolemia after the tumor ruptures, causing extensive bleeding. Owners of the affected dogs often discover that the dog has hemangiosarcoma only after the dog collapses.

The tumor most often appears on the spleen, right heart base, or liver, although varieties also appear on or under the skin or in other locations. It is the most common tumor of the heart, and occurs in the right atrium or right auricular appendage. Here it can cause right-sided heart failure, arrhythmias, pericardial effusion, and cardiac tamponade. Hemangiosarcoma of the spleen or liver is the most common tumor to cause hemorrhage in the abdomen.[4] Hemorrhage secondary to splenic and hepatic tumors can also cause ventricular arrythmias. Hemangiosarcoma of the skin usually appears as a small red or bluish-black lump. It can also occur under the skin. It is suspected that in the skin, hemangiosarcoma is caused by sun exposure.[4] Occasionally, hemangiosarcoma of the skin can be a metastasis from visceral hemangiosarcoma. Other sites the tumor may occur include bone, kidneys, the bladder, muscle, the mouth, and the central nervous system.

Clinical features

Presenting complaints and clinical signs are usually related to the site of origin of the primary tumor or to the presence of metastases, spontaneous tumor rupture, coagulopathies, or cardiac arrhythmias. More than 50% of patients are presented because of acute collapse after spontaneous rupture of the primary tumor or its metastases. Some episodes of collapse are a result of ventricular arrhythmias, which are relatively common in dogs with splenic or cardiac HSA.[5]

Most common clinical signs of visceral hemangiosarcoma include loss of appetite, arrhythmias, weight loss, weakness, lethargy, collapse, pale mucous membranes, and/or sudden death. An enlarged abdomen is often seen due to hemorrhage. Metastasis is most commonly to the liver, omentum, lungs, or brain.

A retrospective study published in 1999 by Ware, et al., found a five times greater risk of cardiac hemangiosarcoma in spayed vs. intact female dogs and a 2.4 times greater risk of hemangiosarcoma in neutered dogs as compared to intact males. The validity of this study is in dispute.[6]

Clinicopathologic findings

Hemangiosarcoma can cause a wide variety of hematologic and hemostatic abnormalities, including anemia, thrombocytopenia[7] (low platelet count), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC); presence of nRBC, schistocytes, and acanthocytes in the blood smear; and leukocytosis with neutrophilia, left shift, and monocytosis.[8][9][10][11]

Diagnosis

A definitive diagnosis requires biopsy and histopathology. Cytologic aspirates may be inconclusive with studies reporting various specificity, and negative results may not correlate with absence of disease, as one study concludes "cytological diagnosis of splenic neoplasia is reliable, but a negative result cannot be used to exclude the possibility of splenic neoplasia."[12] This is because of frequent blood contamination and poor exfoliation.[13] Surgical biopsy is the typical approach in veterinary medicine.

Imaging modalities may include one ore more of ultrasound, CT, MRI[14][15] and FDG-PET/CT.[16][17] FGD-PET/CT may show some benefit over traditional CT for staging and detection of metastasis.[17][18]

Symptoms

Dogs rarely show symptoms of hemangiosarcoma until after the tumor ruptures, causing extensive bleeding. Then symptoms can include short-term lethargy, loss of appetite, enlarged abdomen, weakness in the back legs, paled colored tongue and gums, rapid heart rate, and a weak pulse.[19]

Treatments

Treatment includes chemotherapy and, where practical, removal of the tumor with the affected organ, such as with a splenectomy. Splenectomy alone gives an average survival time of 1–3 months. The addition of chemotherapy, primarily comprising the drug doxorubicin, alone or in combination with other drugs, can increase the average survival time by 2–4 months beyond splenectomy alone.

A 2012 paper published the University of Pennsylvania Veterinary School, in dogs treated with a compound derived from the Coriolus versicolor (commonly known as "Turkey Tail") mushroom showed a favorable response to the agent compared to historical controls of dogs treated with splenectomy and Doxorubicin .:[20]. A controlled, randomized study in 101 dogs was later conducted by the University of Pennsylvania Veterinary School which showed that the Coriolus versicolor mushroom did not have the same outcome noted in the 2012 paper with 15 dogs. In the 2022 paper by Gednet et al. dogs treated with splenectomy followed by Doxorubicin did better then dogs treated with splenectomy and mushroom agent. Combination of Doxorubicin with the Turkey Tail mushroom also did not improve survival when compared to Doxorubicin alone. However, as noted in the 2012 study, the Turkey Tail mushroom extract did not cause any systemic adverse reactions, even when combined with Doxorubicin.:[21].

In the skin, it can be cured in most cases with complete surgical removal as long as there is not visceral involvement.[4] Median survival times for stage I is 780 days, where more advanced stages can range from 172 to 307 days.[22]

References

- "Toxnet Has Moved".

- Dickerson, Erin; Bryan, Brad (2015). "Beta Adrenergic Signaling: A Targetable Regulator of Angiosarcoma and Hemangiosarcoma". Veterinary Sciences. 2 (3): 270–292. doi:10.3390/vetsci2030270. PMC 5644640. PMID 29061946.

- Ettinger, Stephen J.; Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-6795-3.

- Morrison, Wallace B. (1998). Cancer in Dogs and Cats (1st ed.). Williams and Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-06105-4.

- Nelson; et al. (2005). Manual of Small Animal Internal Medicine. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Mosby.

- Personal communication; Modiano, Sackmann

- Ng, C. Y.; Mills, J. N. (January 1985). "Clinical and haematological features of haemangiosarcoma in dogs". Australian Veterinary Journal. 62 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.1985.tb06029.x. ISSN 0005-0423. PMID 4039924.

- Yamamoto, Shinya; Hoshi, Katsuichiro; Hirakawa, Atsushi; Chimura, Syuuichi; Kobayashi, Masayuki; Machida, Noboru (2013). "Epidemiological, Clinical and Pathological Features of Primary Cardiac Hemangiosarcoma in Dogs: A Review of 51 Cases". Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. advpub: 13–0064. doi:10.1292/jvms.13-0064.

- Martins, B. D. C.; Torres, B. B. J.; Rodriguez, A. a. M.; Gamba, C. O.; Cassali, G. D.; Lavalle, G. E.; Martins, G. D. C.; Melo, E. G. (April 2013). "Clinical and pathological aspects of multicentric hemangiosarcoma in a Pinscher dog". Arquivo Brasileiro de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia. 65: 322–328. ISSN 0102-0935.

- Johannes, Chad M.; Henry, Carolyn J.; Turnquist, Susan E.; Hamilton, Terrance A.; Smith, Annette N.; Chun, Ruthanne; Tyler, Jeff W. (2007-12-15). "Hemangiosarcoma in cats: 53 cases (1992–2002)". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 231 (12): 1851–1856. doi:10.2460/javma.231.12.1851.

- Smith, Annette N. (2003-05-01). "Hemangiosarcoma in dogs and cats". Veterinary Clinics: Small Animal Practice. 33 (3): 533–552. doi:10.1016/S0195-5616(03)00002-0. ISSN 0195-5616. PMID 12852235.

- Tecilla, Marco; Gambini, Matteo; Forlani, Annalisa; Caniatti, Mario; Ghisleni, Gabriele; Roccabianca, Paola (2019-11-07). "Evaluation of cytological diagnostic accuracy for canine splenic neoplasms: An investigation in 78 cases using STARD guidelines". PLOS ONE. 14 (11): e0224945. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1424945T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224945. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6837434. PMID 31697755.

- Sharma, Diya (August 2012). "Hemangiosarcoma in a geriatric Labrador retriever". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 53 (8): 889–892. ISSN 0008-5286. PMC 3398530. PMID 23372199.

- Carloni, Andrea; Terragni, Rossella; Morselli‐Labate, Antonio Maria; Paninarova, Michaela; Graham, John; Valenti, Paola; Alberti, Monica; Albarello, Giulia; Millanta, Francesca; Vignoli, Massimo (2019). "Prevalence, distribution, and clinical characteristics of hemangiosarcoma-associated skeletal muscle metastases in 61 dogs: A whole body computed tomographic study". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 33 (2): 812–819. doi:10.1111/jvim.15456. ISSN 1939-1676. PMC 6430957. PMID 30793807.

- Lee, Mokhyeon; Park, Jiyoung; Choi, Hojung; Lee, Haebeom; Jeong, Seong Mok (November 2018). "Presurgical assessment of splenic tumors in dogs: a retrospective study of 57 cases (2012–2017)". Journal of Veterinary Science. 19 (6): 827–834. doi:10.4142/jvs.2018.19.6.827. ISSN 1229-845X. PMC 6265589. PMID 30173499.

- "Characterization of canine hemangiosarcoma by 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography" (PDF). Japanese Journal of Veterinary Research. 2020-08-22.

- Borgatti, Antonella; Winter, Amber L.; Stuebner, Kathleen; Scott, Ruth; Ober, Christopher P.; Anderson, Kari L.; Feeney, Daniel A.; Vallera, Daniel A.; Koopmeiners, Joseph S.; Modiano, Jaime F.; Froelich, Jerry (2017-02-21). "Evaluation of 18-F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) as a staging and monitoring tool for dogs with stage-2 splenic hemangiosarcoma – A pilot study". PLOS ONE. 12 (2): e0172651. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1272651B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172651. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5319762. PMID 28222142.

- Spriet, Mathieu; Willcox, Jennifer L.; Culp, William T. N. (2019). "Role of Positron Emission Tomography in Imaging of Non-neurologic Disorders of the Head, Neck, and Teeth in Veterinary Medicine". Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 6: 180. doi:10.3389/fvets.2019.00180. ISSN 2297-1769. PMC 6579945. PMID 31245395.

- Farricelli, Adrienne. "The Silent Killer: Hemangiosarcomas or a Ruptured, Bleeding Spleen in Dogs". PetHelpful. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Compound Derived From a Mushroom Lengthens Survival Time in Dogs With Cancer, Penn Vet Study Finds". University of Pennsylvania.

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/vco.12823.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Ward, H.; Fox, L. E.; Calderwood-Mays, M. B.; Hammer, A. S.; Couto, C. G. (September 1994). "Cutaneous hemangiosarcoma in 25 dogs: a retrospective study". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 8 (5): 345–348. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.1994.tb03248.x. ISSN 0891-6640. PMID 7837111.

External links

- "Flat-Coated Retriever Hemangiosarcoma". AKC.org.

- "Heart hemangiosarcoma in Cats and Dogs". Pet Cancer Center.

- "Hemangiosarcoma". Canine Cancer Awareness. - includes links to current studies

- "Hemangiosarcoma". Cure Hemangiosarcoma. - includes links to current and past studies of hemangiosarcoma

- "Hemangiosarcoma". Mar Vista Animal Medical Center. Archived from the original on 2004-02-03. Retrieved 2004-01-27.

- "Hemangiosarcoma". Vetinfo.

- "Hemangiosarcoma in Cats and Dogs". Pet Cancer Center.

- "Hemangiosarcoma research". Modiano Lab of the Univ. of Minnesota. - includes links to other canine cancer research

- "Vet Corner: Hemangiosarcoma". Adopt a Golden Retriever. Archived from the original on 2003-12-15. Retrieved 2004-01-27.