Kidney dialysis

Kidney dialysis (from Greek διάλυσις, dialysis, 'dissolution'; from διά, dia, 'through', and λύσις, lysis, 'loosening or splitting') is the process of removing excess water, solutes, and toxins from the blood in people whose kidneys can no longer perform these functions naturally. This is referred to as renal replacement therapy. The first successful dialysis was performed in 1943.

| Kidney dialysis | |

|---|---|

Patient receiving hemodialysis | |

| Specialty | nephrology |

| ICD-9-CM | 39.95 |

| MeSH | D006435 |

.svg.png.webp)

Dialysis may need to be initiated when there is a sudden rapid loss of kidney function, known as acute kidney injury (previously called acute renal failure), or when a gradual decline in kidney function, chronic kidney disease, reaches stage 5. Stage 5 chronic renal failure is reached when the glomerular filtration rate is 10–15% of normal, creatinine clearance is less than 10 mL per minute and uremia is present.[1]

Dialysis is used as a temporary measure in either acute kidney injury or in those awaiting kidney transplant and as a permanent measure in those for whom a transplant is not indicated or not possible.[2]

In Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, dialysis is paid for by the government for those who are eligible.[3]

In research laboratories, dialysis technique can also be used to separate molecules based on their size. Additionally, it can be used to balance buffer between a sample and the solution "dialysis bath" or "dialysate"[4] that the sample is in. For dialysis in a laboratory, a tubular semipermeable membrane made of cellulose acetate or nitrocellulose is used.[5] Pore size is varied according to the size separation required with larger pore sizes allowing larger molecules to pass through the membrane. Solvents, ions and buffer can diffuse easily across the semipermeable membrane, but larger molecules are unable to pass through the pores. This can be used to purify proteins of interest from a complex mixture by removing smaller proteins and molecules.

Background

The kidneys have an important role in maintaining health. When the person is healthy, the kidneys maintain the body's internal equilibrium of water and minerals (sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, sulphate). The acidic metabolism end-products that the body cannot get rid of via respiration are also excreted through the kidneys. The kidneys also function as a part of the endocrine system, producing erythropoietin, calcitriol and renin. Erythropoietin is involved in the production of red blood cells and calcitriol plays a role in bone formation.[6] Dialysis is an imperfect treatment to replace kidney function because it does not correct the compromised endocrine functions of the kidney. Dialysis treatments replace some of these functions through diffusion (waste removal) and ultrafiltration (fluid removal).[7] Dialysis uses highly purified (also known as "ultrapure") water.[8]

Principle

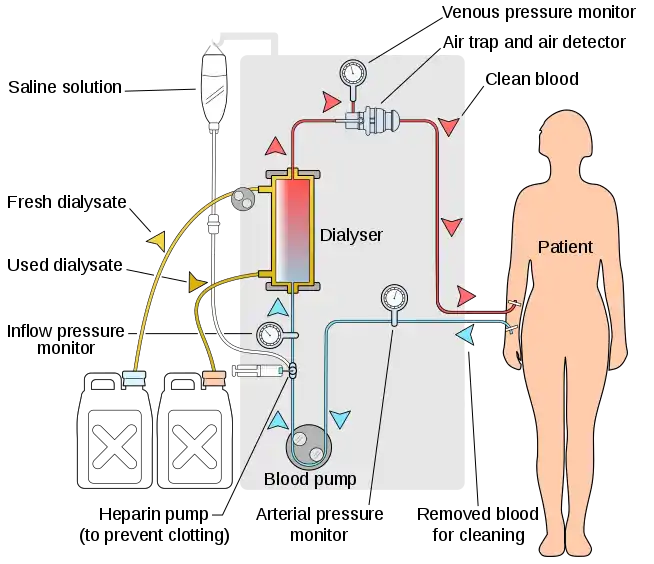

Dialysis works on the principles of the diffusion of solutes and ultrafiltration of fluid across a semi-permeable membrane. Diffusion is a property of substances in water; substances in water tend to move from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration.[9] Blood flows by one side of a semi-permeable membrane, and a dialysate, or special dialysis fluid, flows by the opposite side. A semipermeable membrane is a thin layer of material that contains holes of various sizes, or pores. Smaller solutes and fluid pass through the membrane, but the membrane blocks the passage of larger substances (for example, red blood cells and large proteins). This replicates the filtering process that takes place in the kidneys when the blood enters the kidneys and the larger substances are separated from the smaller ones in the glomerulus.[9]

The two main types of dialysis, hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, remove wastes and excess water from the blood in different ways.[2] Hemodialysis removes wastes and water by circulating blood outside the body through an external filter, called a dialyzer, that contains a semipermeable membrane. The blood flows in one direction and the dialysate flows in the opposite. The counter-current flow of the blood and dialysate maximizes the concentration gradient of solutes between the blood and dialysate, which helps to remove more urea and creatinine from the blood. The concentrations of solutes normally found in the urine (for example potassium, phosphorus and urea) are undesirably high in the blood, but low or absent in the dialysis solution, and constant replacement of the dialysate ensures that the concentration of undesired solutes is kept low on this side of the membrane. The dialysis solution has levels of minerals like potassium and calcium that are similar to their natural concentration in healthy blood. For another solute, bicarbonate, dialysis solution level is set at a slightly higher level than in normal blood, to encourage the diffusion of bicarbonate into the blood, to act as a pH buffer to neutralize the metabolic acidosis that is often present in these patients. The levels of the components of dialysate are typically prescribed by a nephrologist according to the needs of the individual patient.

In peritoneal dialysis, wastes and water are removed from the blood inside the body using the peritoneum as a natural semipermeable membrane. Wastes and excess water move from the blood, across the peritoneal membrane and into a special dialysis solution, called dialysate, in the abdominal cavity.

Types

There are three primary and two secondary types of dialysis: hemodialysis (primary), peritoneal dialysis (primary), hemofiltration (primary), hemodiafiltration (secondary) and intestinal dialysis (secondary).

Hemodialysis

In hemodialysis, the patient's blood is pumped through the blood compartment of a dialyzer, exposing it to a partially permeable membrane. The dialyzer is composed of thousands of tiny hollow synthetic fibers. The fiber wall acts as the semipermeable membrane. Blood flows through the fibers, dialysis solution flows around the outside of the fibers, and water and wastes move between these two solutions.[10] The cleansed blood is then returned via the circuit back to the body. Ultrafiltration occurs by increasing the hydrostatic pressure across the dialyzer membrane. This usually is done by applying a negative pressure to the dialysate compartment of the dialyzer. This pressure gradient causes water and dissolved solutes to move from blood to dialysate and allows the removal of several litres of excess fluid during a typical 4-hour treatment. In the United States, hemodialysis treatments are typically given in a dialysis center three times per week (due in the United States to Medicare reimbursement rules); however, as of 2005 over 2,500 people in the United States are dialyzing at home more frequently for various treatment lengths.[11] Studies have demonstrated the clinical benefits of dialyzing 5 to 7 times a week, for 6 to 8 hours. This type of hemodialysis is usually called nocturnal daily hemodialysis and a study has shown it provides a significant improvement in both small and large molecular weight clearance and decreases the need for phosphate binders.[12] These frequent long treatments are often done at home while sleeping, but home dialysis is a flexible modality and schedules can be changed day to day, week to week. In general, studies show that both increased treatment length and frequency are clinically beneficial.[13]

Hemo-dialysis was one of the most common procedures performed in U.S. hospitals in 2011, occurring in 909,000 stays (a rate of 29 stays per 10,000 population).[14]

Peritoneal dialysis

In peritoneal dialysis, a sterile solution containing glucose (called dialysate) is run through a tube into the peritoneal cavity, the abdominal body cavity around the intestine, where the peritoneal membrane acts as a partially permeable membrane.

This exchange is repeated 4–5 times per day; automatic systems can run more frequent exchange cycles overnight. Peritoneal dialysis is less efficient than hemodialysis, but because it is carried out for a longer period of time the net effect in terms of removal of waste products and of salt and water are similar to hemodialysis. Peritoneal dialysis is carried out at home by the patient, often without help. This frees patients from the routine of having to go to a dialysis clinic on a fixed schedule multiple times per week. Peritoneal dialysis can be performed with little to no specialized equipment (other than bags of fresh dialysate).

Hemofiltration

.svg.png.webp)

Hemofiltration is a similar treatment to hemodialysis, but it makes use of a different principle. The blood is pumped through a dialyzer or "hemofilter" as in dialysis, but no dialysate is used. A pressure gradient is applied; as a result, water moves across the very permeable membrane rapidly, "dragging" along with it many dissolved substances, including ones with large molecular weights, which are not cleared as well by hemodialysis. Salts and water lost from the blood during this process are replaced with a "substitution fluid" that is infused into the extracorporeal circuit during the treatment.

Hemodiafiltration

Hemodiafiltration is a combination between hemodialysis and hemofiltration, thus used to purify the blood from toxins when the kidney is not working normally and also used to treat acute kidney injury (AKI).

Intestinal dialysis

.svg.png.webp)

In intestinal dialysis, the diet is supplemented with soluble fibres such as acacia fibre, which is digested by bacteria in the colon. This bacterial growth increases the amount of nitrogen that is eliminated in fecal waste.[15][16] An alternative approach utilizes the ingestion of 1 to 1.5 liters of non-absorbable solutions of polyethylene glycol or mannitol every fourth hour.[17]

Indications

The decision to initiate dialysis or hemofiltration in patients with kidney failure depends on several factors. These can be divided into acute or chronic indications.

Depression and kidney failure symptoms can be similar to each other. It's important that there's open communication between a dialysis team and the patient. Open communication will allow giving a better quality of life. Knowing the patients' needs will allow the dialysis team to provide more options like: changes in dialysis type like home dialysis for patients to be able to be more active or changes in eating habits to avoid unnecessary waste products.

Acute indications

Indications for dialysis in a patient with acute kidney injury are summarized with the vowel mnemonic of "AEIOU":[18]

- Acidemia from metabolic acidosis in situations in which correction with sodium bicarbonate is impractical or may result in fluid overload.

- Electrolyte abnormality, such as severe hyperkalemia, especially when combined with AKI.

- Intoxication, that is, acute poisoning with a dialyzable substance. These substances can be represented by the mnemonic SLIME: salicylic acid, lithium, isopropanol, magnesium-containing laxatives and ethylene glycol.

- Overload of fluid not expected to respond to treatment with diuretics

- Uremia complications, such as pericarditis, encephalopathy, or gastrointestinal bleeding.

Chronic indications

Chronic dialysis may be indicated when a patient has symptomatic kidney failure and low glomerular filtration rate (GFR < 15 mL/min).[19] Between 1996 and 2008, there was a trend to initiate dialysis at progressively higher estimated GFR, eGFR. A review of the evidence shows no benefit or potential harm with early dialysis initiation, which has been defined by start of dialysis at an estimated GFR of greater than 10 ml/min/1.732. Observational data from large registries of dialysis patients suggests that early start of dialysis may be harmful.[20] The most recent published guidelines from Canada, for when to initiate dialysis, recommend an intent to defer dialysis until a patient has definite kidney failure symptoms, which may occur at an estimated GFR of 5–9 ml/min/1.732.[21]

Dialyzable substances

Characteristics

Dialyzable substances—substances removable with dialysis—have these properties:

- Low molecular mass

- High water solubility

- Low protein binding capacity

- Prolonged elimination (long half-life)

- Small volume of distribution

Substances

- Ethylene glycol

- Procainamide

- Methanol

- Isopropyl alcohol

- Barbiturates

- Lithium

- Bromide

- Sotalol

- Chloral hydrate

- Ethanol

- Acetone

- Atenolol

- Theophylline

- Salicylates

- Baclofen

Pediatric dialysis

Over the past 20 years, children have benefited from major improvements in both technology and clinical management of dialysis. Morbidity during dialysis sessions has decreased with seizures being exceptional and hypotensive episodes rare. Pain and discomfort have been reduced with the use of chronic internal jugular venous catheters and anesthetic creams for fistula puncture. Non-invasive technologies to assess patient target dry weight and access flow can significantly reduce patient morbidity and health care costs. Mortality in paediatric and young adult patients on chronic hemodialysis is associated with multifactorial markers of nutrition, inflammation, anaemia and dialysis dose, which highlights the importance of multimodal intervention strategies besides adequate hemodialysis treatment as determined by Kt/V alone.[22]

Biocompatible synthetic membranes, specific small size material dialyzers and new low extra-corporeal volume tubing have been developed for young infants. Arterial and venous tubing length is made of minimum length and diameter, a <80 ml to <110 ml volume tubing is designed for pediatric patients and a >130 to <224 ml tubing are for adult patients, regardless of blood pump segment size, which can be of 6.4 mm for normal dialysis or 8.0mm for high flux dialysis in all patients. All dialysis machine manufacturers design their machine to do the pediatric dialysis. In pediatric patients, the pump speed should be kept at low side, according to patient blood output capacity, and the clotting with heparin dose should be carefully monitored. The high flux dialysis (see below) is not recommended for pediatric patients.

In children, hemodialysis must be individualized and viewed as an "integrated therapy" that considers their long-term exposure to chronic renal failure treatment. Dialysis is seen only as a temporary measure for children compared with renal transplantation because this enables the best chance of rehabilitation in terms of educational and psychosocial functioning. Long-term chronic dialysis, however, the highest standards should be applied to these children to preserve their future "cardiovascular life"—which might include more dialysis time and on-line hemodiafiltration online hdf with synthetic high flux membranes with the surface area of 0.2 m2 to 0.8 m2 and blood tubing lines with the low volume yet large blood pump segment of 6.4/8.0 mm, if we are able to improve on the rather restricted concept of small-solute urea dialysis clearance.

Dialysis in different countries

In the United Kingdom

The National Health Service provides dialysis in the United Kingdom. In England, the service is commissioned by NHS England. About 23,000 patients use the service each year.[23] Patient transport services are generally provided without charge, for patients who need to travel to dialysis centres. Cornwall Clinical Commissioning Group proposed to restrict this provision to patients who did not have specific medical or financial reasons in 2018 but changed their minds after a campaign led by Kidney Care UK and decided to fund transport for patients requiring dialysis three times a week for a minimum or six times a month for a minimum of three months.[24]

A UK study found that receiving dialysis at home is less costly than receiving dialysis in hospital.[25][26] However, many people in the UK prefer to receive dialysis in hospital for various reasons such as providing regular social contact. Encouraging people to have dialysis at home could lead to savings for the NHS, as well as reducing the impact of dialysis on people's social and professional lives.[25][27]

In the United States

Since 1972, insurance companies in the United States have covered the cost of dialysis and transplants for all citizens.[28] By 2014, more than 460,000 Americans were undergoing treatment, the costs of which amount to six percent of the entire Medicare budget. Kidney disease is the ninth leading cause of death, and the U.S. has one of the highest mortality rates for dialysis care in the industrialized world. The rate of patients getting kidney transplants has been lower than expected. These outcomes have been blamed on a new for-profit dialysis industry responding to government payment policies.[29][30][31] A 1999 study concluded that "patients treated in for-profit dialysis facilities have higher mortality rates and are less likely to be placed on the waiting list for a renal transplant than are patients who are treated in not-for-profit facilities", possibly because transplantation removes a constant stream of revenue from the facility.[32] The insurance industry has complained about kickbacks and problematic relationships between charities and providers.[33]

In China

The Government of China provides the funding for dialysis treatment. There is a challenge to reach everyone who needs dialysis treatment because of the unequal distribution of health care resources and dialysis centers.[34] There are 395,121 individuals who receive hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis in China per year. The percentage of the Chinese population with chronic kidney disease is 10.8%.[35] The Chinese Government is trying to increase the amount of peritoneal dialysis taking place to meet the needs of the nation's individuals with chronic kidney disease.[36]

History

In 1913, Leonard Rowntree and John Abel of Johns Hopkins Hospital developed the first dialysis system which they successfully tested in animals.[37] A Dutch doctor, Willem Johan Kolff, constructed the first working dialyzer in 1943 during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands.[38] Due to the scarcity of available resources, Kolff had to improvise and build the initial machine using sausage casings, beverage cans, a washing machine and various other items that were available at the time. Over the following two years (1944–1945), Kolff used his machine to treat 16 patients with acute kidney failure, but the results were unsuccessful. Then, in 1945, a 67-year-old comatose woman regained consciousness following 11 hours of hemodialysis with the dialyzer and lived for another seven years before dying from an unrelated condition. She was the first-ever patient successfully treated with dialysis.[38] Gordon Murray of the University of Toronto independently developed a dialysis machine in 1945. Unlike Kolff's rotating drum, Murray's machine used fixed flat plates, more like modern designs.[39] Like Kolff, Murray's initial success was in patients with acute renal failure.[40] Nils Alwall of Lund University in Sweden modified a similar construction to the Kolff dialysis machine by enclosing it inside a stainless steel canister. This allowed the removal of fluids, by applying a negative pressure to the outside canister, thus making it the first truly practical device for hemodialysis. Alwall treated his first patient in acute kidney failure on 3 September 1946.[41]

See also

- Thomas Graham (chemist), the founder of dialysis and father of colloid chemistry

- Dialysis tubing

- List of US dialysis providers

- Vitamin and mineral management for dialysis

- Nephrology

- Hepatorenal syndrome

References

- AMGEN Canada Inc. Essential Concepts in Chronic Renal Failure. A Practical Continuing Education Series. Mississauga, 2008: p. 36.

- Pendse S, Singh A, Zawada E. "Initiation of Dialysis". In: Handbook of Dialysis. 4th ed. New York; 2008:14–21

- "Financial Help for Treatment of Kidney Failure". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 2021-04-14.

- Garrett RH, Grisham CM (2013). Biochemistry (5th ed.). p. 107. ISBN 978-1-133-10629-6.

- Ninfa AJ, Ballou DP, Benore M (2009). Fundamental Laboratory Approaches for Biochemistry and Biotechnology (2nd ed.). p. 45. ISBN 978-0-470-08766-4.

- Brundage D. Renal Disorders. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1992

- "Atlas of Diseases of the Kidney, Volume 5, Principles of Dialysis: Diffusion, Convection, and Dialysis Machines" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2011-09-02.

- "Home Hemodialysis and Water Treatment". Davita. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- Mosby’s Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, & Health Professions. 7th ed. St. Louis, MO; Mosby: 2006

- Ahmad S, Misra Hemodialysis Apparatus. In: Handbook of Dialysis. 4th ed. New York, NY; 2008:59-78.

- "USRDS Treatment Modalities" (PDF). United States Renal Data System. Retrieved 2011-09-02.

- Rocco MV (July 2007). "More frequent hemodialysis: back to the future?". Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease. 14 (3): e1–e9. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2007.04.006. PMID 17603969.

- Daily therapy study results compared Archived March 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Pfuntner A., Wier L.M., Stocks C. Most Frequent Procedures Performed in U.S. Hospitals, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #165. October 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. .

- Al-Mosawi AJ (October 2004). "Acacia gum supplementation of a low-protein diet in children with end-stage renal disease". Pediatric Nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 19 (10): 1156–9. doi:10.1007/s00467-004-1562-5. PMID 15293039. S2CID 25163553.

- Ali AA, Ali KE, Fadlalla AE, Khalid KE (January 2008). "The effects of gum arabic oral treatment on the metabolic profile of chronic renal failure patients under regular haemodialysis in Central Sudan". Natural Product Research. 22 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1080/14786410500463544. PMID 17999333. S2CID 1905987.

- Miskowiak J (1991). "Continuous intestinal dialysis for uraemia by intermittent oral intake of non-absorbable solutions. An experimental study". Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 25 (1): 71–4. doi:10.3109/00365599109024532. PMID 1904625.

- Irwin RS, Rippe JM (2008). Irwin and Rippe's intensive care medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 988–999. ISBN 978-0-7817-9153-3.

- Tattersall J, Dekker F, Heimbürger O, Jager KJ, Lameire N, Lindley E, et al. (July 2011). "When to start dialysis: updated guidance following publication of the Initiating Dialysis Early and Late (IDEAL) study". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 26 (7): 2082–2086. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfr168. PMID 21551086.

- Rosansky S, Glassock RJ, Clark WF (May 2011). "Early start of dialysis: a critical review". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 6 (5): 1222–1228. doi:10.2215/cjn.09301010. PMID 21555505.

- Nesrallah GE, Mustafa RA, Clark WF, Bass A, Barnieh L, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. (February 2014). "Canadian Society of Nephrology 2014 clinical practice guideline for timing the initiation of chronic dialysis". CMAJ. 186 (2): 112–117. doi:10.1503/cmaj.130363. PMC 3903737. PMID 24492525.

- Gotta V, Tancev G, Marsenic O, Vogt JE, Pfister M (February 2021). "Identifying key predictors of mortality in young patients on chronic haemodialysis-a machine learning approach". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 36 (3): 519–528. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfaa128. PMID 32510143.

- Hazell W (13 March 2015). "Specialised service transfer reconsidered due to incorrect data". Health Service Journal. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- "CCG backs down over patient transport funding cuts". Health Service Journal. 10 April 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- "Why don't people have kidney dialysis at home?". NIHR Evidence. 2022-08-10. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_52322. S2CID 251513385.

- Roberts G, Holmes J, Williams G, Chess J, Hartfiel N, Charles JM, et al. (January 2022). "Current costs of dialysis modalities: A comprehensive analysis within the United Kingdom". Peritoneal Dialysis International: 8968608211061126. doi:10.1177/08968608211061126. PMID 35068280. S2CID 246239905.

- Mc Laughlin L, Williams G, Roberts G, Dallimore D, Fellowes D, Popham J, et al. (April 2022). "Assessing the efficacy of coproduction to better understand the barriers to achieving sustainability in NHS chronic kidney services and create alternate pathways". Health Expectations. 25 (2): 579–606. doi:10.1111/hex.13391. PMC 8957730. PMID 34964215.

- Rettig RA (1991). "Origins of the Medicare Kidney Disease Entitlement: The Social Security Amendments of 1972". In Hanna KE (ed.). Biomedical Politics. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. doi:10.17226/1793. ISBN 978-0-309-04486-8. PMID 25121217.

- Fields R (2010-11-09). "In Dialysis, Life-Saving Care at Great Risk and Cost". ProPublica. Retrieved 2017-05-18.

- "John Oliver sees ills in for-profit dialysis centers". Newsweek. 2017-05-15. Retrieved 2017-05-18.

- "Profit motive linked to dialysis deaths - UB Reporter". www.buffalo.edu. Retrieved 2017-05-18.

- Garg PP, Frick KD, Diener-West M, Powe NR (November 1999). "Effect of the ownership of dialysis facilities on patients' survival and referral for transplantation". The New England Journal of Medicine. 341 (22): 1653–1660. doi:10.1056/NEJM199911253412205. PMID 10572154. S2CID 45158008.

- Abelsonm R, Thomas K (2016-07-01). "UnitedHealthcare Sues Dialysis Chain Over Billing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-05-18.

- Jin J, Wang J, Ma X, Wang Y, Li R (April 2015). "Equality of Medical Health Resource Allocation in China Based on the Gini Coefficient Method". Iranian Journal of Public Health. 44 (4): 445–457. PMC 4441957. PMID 26056663.

- Zhang L, Wang F, Wang L, Wang W, Liu B, Liu J, et al. (March 2012). "Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: a cross-sectional survey". Lancet. 379 (9818): 815–822. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60033-6. PMID 22386035. S2CID 43174392.

- Li PK, Lui SL, Ng JK, Cai GY, Chan CT, Chen HC, et al. (December 2017). "Addressing the burden of dialysis around the world: A summary of the roundtable discussion on dialysis economics at the First International Congress of Chinese Nephrologists 2015". Nephrology. 22 (Suppl 4): 3–8. doi:10.1111/nep.13143. PMID 29155495.

- Abel JJ, Rowntree LG, Turner BB (1990). "On the removal of diffusable substances from the circulating blood by means of dialysis. Transactions of the Association of American Physicians, 1913". Transfusion Science. 11 (2): 164–5. PMID 10160880.

- Blakeslee S (12 February 2009). "Willem Kolff, Doctor Who Invented Kidney and Heart Machines, Dies at 97". The New York Times.

- McAlister VC (September 2005). "Clinical kidney transplantation: a 50th anniversary review of the first reported series". American Journal of Surgery. 190 (3): 485–488. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.04.016. PMID 16105541.

- Murray G, Delorme E, Thomas N (November 1947). "Development of an artificial kidney; experimental and clinical experiences". Archives of Surgery. 55 (5): 505–522. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1947.01230080514001. PMID 20271745.

- Kurkus J, Ostrowski J (August 2019). "Nils Alwall and his artificial kidneys: Seventieth anniversary of the start of serial production". Artificial Organs. 43 (8): 713–718. doi:10.1111/aor.13545. PMID 31389617. S2CID 199467973.

Bibliography

- Al-Mosawi AJ (October 2004). "Acacia gum supplementation of a low-protein diet in children with end-stage renal disease". Pediatric Nephrology. 19 (10): 1156–1159. doi:10.1007/s00467-004-1562-5. PMID 15293039. S2CID 25163553.

- Al Mosawi AJ (October 2007). "The use of acacia gum in end stage renal failure". Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 53 (5): 362–365. doi:10.1093/tropej/fmm033. PMID 17517814.

- Ali AA, Ali KE, Fadlalla AE, Khalid KE (January 2008). "The effects of gum arabic oral treatment on the metabolic profile of chronic renal failure patients under regular haemodialysis in Central Sudan". Natural Product Research. 22 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1080/14786410500463544. PMID 17999333. S2CID 1905987.

- Miskowiak J (1991). "Continuous intestinal dialysis for uraemia by intermittent oral intake of non-absorbable solutions. An experimental study". Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 25 (1): 71–74. doi:10.3109/00365599109024532. PMID 1904625.

Further reading

- Crowther S, Reynolds L, Tansey T, eds. (2009). History of dialysis in the UK c.1950-1980 : the transcript of a Witness Seminar held by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, London, on 26 February 2008. London: Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL. ISBN 978-0-85484-122-6.

External links

- "Machine Cleans Blood While You Wait"—1950 article on early use of dialysis machine at Bellevue Hospital New York City—an example of how complex and large early dialysis machines were

- Home Dialysis Museum—History and pictures of dialysis machines through time

- Introduction to Dialysis Machines—Tutorial describing the main subfunctions of dialysis systems.

- "First Nations man conducts own dialysis treatments to avoid move to the city"—CBC News (November 30, 2016)