Medicare (United States)

Medicare is a government national health insurance program in the United States, begun in 1965 under the Social Security Administration (SSA) and now administered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). It primarily provides health insurance for Americans aged 65 and older, but also for some younger people with disability status as determined by the SSA, including people with end stage renal disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig's disease).

In 2018, according to the 2019 Medicare Trustees Report, Medicare provided health insurance for over 59.9 million individuals—more than 52 million people aged 65 and older and about 8 million younger people.[1] According to annual Medicare Trustees reports and research by the government's MedPAC group, Medicare covers about half of healthcare expenses of those enrolled. Enrollees almost always cover most of the remaining costs by taking additional private insurance and/or by joining a public Part C or Part D Medicare health plan.[2] In 2020, US federal government spending on Medicare was $776.2 billion.[3]

No matter which of those two options the beneficiaries choose—or if they choose to do nothing, beneficiaries also have other healthcare-related costs. These additional costs can include deductibles and co-pays; the costs of uncovered services—such as for long-term custodial, dental, hearing, and vision care; the cost of annual physical exams (for those not on Part C health plans that include physicals); and the costs related to basic Medicare's lifetime and per-incident limits. Medicare is funded by a combination of a specific payroll tax, beneficiary premiums, and surtaxes from beneficiaries, co-pays and deductibles, and general U.S. Treasury revenue.

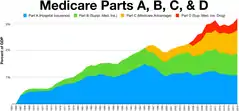

Medicare Parts. Medicare is divided into four Parts: A, B, C and D. Part A covers hospital, skilled nursing, and hospice services. Part B covers outpatient services. Part D covers self-administered prescription drugs. Additionally, Part C is an alternative that allows patients to choose their own plans that provide the same services as Parts A and B, but with additional benefits. The specific details on these four plans are as follows:

- Part A covers hospital (inpatient, formally admitted only), skilled nursing (only after being formally admitted to a hospital for three days and not for custodial care), and hospice services.

- Part B covers outpatient services including some providers' services while inpatient at a hospital, outpatient hospital charges, most provider office visits even if the office is "in a hospital", and most professionally administered prescription drugs.

- Part C is an alternative called Managed Medicare or Medicare Advantage, which allows patients to choose health plans with at least the same service coverage as Parts A and B (and most often more), often the benefits of Part D, and always an annual out-of-pocket expense limit which A and B lack. A beneficiary must enroll in Parts A and B first before signing up for Part C.[4]

- Part D covers mostly self-administered prescription drugs.

History

Originally, the name "Medicare" in the United States referred to a program providing medical care for families of people serving in the military as part of the Dependents' Medical Care Act, which was passed in 1956.[5] President Dwight D. Eisenhower held the first White House Conference on Aging in January 1961, in which creating a health care program for social security beneficiaries was proposed.[6][7]

In July 1965,[8] under the leadership of President Lyndon Johnson, Congress enacted Medicare under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act to provide health insurance to people age 65 and older, regardless of income or medical history.[9][10] Johnson signed the Social Security Amendments of 1965 into law on July 30, 1965, at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library in Independence, Missouri. Former President Harry S. Truman and his wife, former First Lady Bess Truman became the first recipients of the program.[11]

Before Medicare was created, only approximately 60% of people over the age of 65 had health insurance, with coverage often unavailable or unaffordable to many others, as older adults paid more than three times as much for health insurance as younger people. Many of this group (about 20% of the total in 2015) became "dual eligible" for both Medicare and Medicaid with the passing of the law. In 1966, Medicare spurred the racial integration of thousands of waiting rooms, hospital floors, and physician practices by making payments to health care providers conditional on desegregation.[12]

Medicare has been operating for just over a half-century and, during that time, has undergone several changes. Since 1965, the program's provisions have expanded to include benefits for speech, physical, and chiropractic therapy in 1972.[13] Medicare added the option of payments to health maintenance organizations (HMO)[13] in the 1970s. The government added hospice benefits to aid elderly people on a temporary basis in 1982,[13] and made this permanent in 1984.

Congress further expanded Medicare in 2001 to cover younger people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig's disease). As the years progressed, Congress expanded Medicare eligibility to younger people with permanent disabilities who receive Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) payments and to those with end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

The association with HMOs that began in the 1970s was formalized and expanded under President Bill Clinton in 1997 as Medicare Part C (although not all Part C health plans sponsors have to be HMOs, about 75% are). In 2003, under President George W. Bush, a Medicare program for covering almost all self-administered prescription drugs was passed (and went into effect in 2006) as Medicare Part D.[14]

Administration

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), administers Medicare, Medicaid, the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), and parts of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) ("Obamacare").[15] Along with the Departments of Labor and Treasury, the CMS also implements the insurance reform provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) and most aspects of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 as amended. The Social Security Administration (SSA) is responsible for determining Medicare eligibility, eligibility for and payment of Extra Help/Low Income Subsidy payments related to Parts C and D of Medicare, and collecting most premium payments for the Medicare program.

The Chief Actuary of the CMS must provide accounting information and cost-projections to the Medicare Board of Trustees to assist them in assessing the program's financial health. The Trustees are required by law to issue annual reports on the financial status of the Medicare Trust Funds, and those reports are required to contain a statement of actuarial opinion by the Chief Actuary.[16][17]

Since the Medicare program began, the CMS (that was not always the name of the responsible bureaucracy) has contracted with private insurance companies to operate as intermediaries between the government and medical providers to administer Part A and Part B benefits. Contracted processes include claims and payment processing, call center services, clinician enrollment, and fraud investigation. Beginning in 1997 and 2005, respectively, these Part A and B administrators (whose contracts are bid out periodically), along with other insurance companies and other companies or organizations (such as integrated health delivery systems, unions and pharmacies), also began administering Part C and Part D plans.

The Specialty Society Relative Value Scale Update Committee (or Relative Value Update Committee; RUC), composed of physicians associated with the American Medical Association, advises the government about pay standards for Medicare patient procedures performed by doctors and other professionals under Medicare Part B.[18] A similar but different CMS process determines the rates paid for acute care and other hospitals—including skilled nursing facilities—under Medicare Part A. The rates paid for both Part A and Part B type services under Part C are whatever is agreed upon between the sponsor and the provider. The amounts paid for mostly self-administered drugs under Part D are whatever is agreed upon between the sponsor (almost always through a pharmacy benefit manager also used in commercial insurance) and pharmaceutical distributors and/or manufacturers.

The expenditures from the trust funds under Parts A and B are fee for service whereas the expenditures from the trust funds under Parts C and D are capitated. In particular, it is important to understand that Medicare itself does not purchase either self-administered or professionally administered drugs. In Part D, the Part D Trust Fund helps beneficiaries purchase drug insurance. For Part B drugs, the trust funds reimburse the professional that administers the drugs and allows a mark up for that service.

Financing

Medicare has several sources of financing.

Part A's inpatient admitted hospital and skilled nursing coverage is largely funded by revenue from a 2.9% payroll tax levied on employers and workers (each pay 1.45%). Until December 31, 1993, the law provided a maximum amount of compensation on which the Medicare tax could be imposed annually, in the same way that the Social Security payroll tax operates.[19] Beginning on January 1, 1994, the compensation limit was removed. Self-employed individuals must calculate the entire 2.9% tax on self-employed net earnings (because they are both employee and employer), but they may deduct half of the tax from the income in calculating income tax.[20] Beginning in 2013, the rate of Part A tax on earned income exceeding $200,000 for individuals ($250,000 for married couples filing jointly) rose to 3.8%, in order to pay part of the cost of the subsidies mandated by the Affordable Care Act.[21]

Parts B and D are partially funded by premiums paid by Medicare enrollees and general U.S. Treasury revenue (to which Medicare beneficiaries contributed and may still contribute). In 2006, a surtax was added to Part B premium for higher-income seniors to partially fund Part D. In the Affordable Care Act legislation of 2010, another surtax was then added to Part D premium for higher-income seniors to partially fund the Affordable Care Act and the number of Part B beneficiaries subject to the 2006 surtax was doubled, also partially to fund PPACA.

Parts A and B/D use separate trust funds to receive and disburse the funds mentioned above. The Medicare Part C program uses these same two trust funds as well at a proportion determined by the CMS reflecting that Part C beneficiaries are fully on Parts A and B of Medicare just as all other beneficiaries, but that their medical needs are paid for through a sponsor (most often an integrated health delivery system or spin out) to providers rather than "fee for service" (FFS) through an insurance company called a Medicare Administrative Contractor to providers.

In 2018, Medicare spending was over $740 billion, about 3.7% of U.S. gross domestic product and over 15% of total US federal spending.[22] Because of the two Trust funds and their differing revenue sources (one dedicated and one not), the Trustees analyze Medicare spending as a percent of GDP rather than versus the Federal budget.

Retirement of the Baby Boom generation is projected by 2030 to increase enrollment to more than 80 million. In addition, the fact that the number of workers per enrollee will decline from 3.7 to 2.4 and that overall health care costs in the nation are rising pose substantial financial challenges to the program. Medicare spending is projected to increase from just over $740 billion in 2018 to just over $1.2 trillion by 2026, or from 3.7% of GDP to 4.7%.[22] Baby-boomers are projected to have longer life spans, which will add to the future Medicare spending. The 2019 Medicare Trustees Report estimates that spending as a percent of GDP will grow to 6% by 2043 (when the last of the baby boomers turns 80) and then flatten out to 6.5% of GDP by 2093. In response to these financial challenges, Congress made substantial cuts to future payouts to providers (primarily acute care hospitals and skilled nursing facilities) as part of PPACA in 2010 and the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) and policymakers have offered many additional competing proposals to reduce Medicare costs further.

Cost reduction is influenced by factors including reduction in inappropriate and unnecessary care by evaluating evidence-based practices as well as reducing the amount of unnecessary, duplicative, and inappropriate care. Cost reduction may also be effected by reducing medical errors, investment in healthcare information technology, improving transparency of cost and quality data, increasing administrative efficiency, and by developing both clinical/non-clinical guidelines and quality standards.[23]

Eligibility

In general, all persons 65 years of age or older who have been legal residents of the United States for at least five years are eligible for Medicare. People with disabilities under 65 may also be eligible if they receive Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) benefits. Specific medical conditions may also help people become eligible to enroll in Medicare.

People qualify for Medicare coverage, and Medicare Part A premiums are entirely waived, if the following circumstances apply:

- They are 65 years or older and US citizens or have been permanent legal residents for five continuous years, and they or their spouses (or qualifying ex-spouses) have paid Medicare taxes for at least 10 years.

- or

- They are under 65, disabled, and have been receiving either Social Security SSDI benefits or Railroad Retirement Board disability benefits; they must receive one of these benefits for at least 24 months from date of entitlement (eligibility for first disability payment) before becoming eligible to enroll in Medicare.

- or

- They get continuing dialysis for end-stage renal disease or need a kidney transplant.

Those who are 65 and older who choose to enroll in Part A Medicare must pay a monthly premium to remain enrolled in Medicare Part A if they or their spouse have not paid the qualifying Medicare payroll taxes.[24]

People with disabilities who receive SSDI are eligible for Medicare while they continue to receive SSDI payments; they lose eligibility for Medicare based on disability if they stop receiving SSDI. The coverage does not begin until 24 months after the SSDI start date. The 24-month exclusion means that people who become disabled must wait two years before receiving government medical insurance, unless they have one of the listed diseases. The 24-month period is measured from the date that an individual is determined to be eligible for SSDI payments, not necessarily when the first payment is actually received. Many new SSDI recipients receive "back" disability pay, covering a period that usually begins six months from the start of disability and ending with the first monthly SSDI payment.

Some beneficiaries are dual-eligible. This means they qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid. In some states for those making below a certain income, Medicaid will pay the beneficiaries' Part B premium for them (most beneficiaries have worked long enough and have no Part A premium), as well as some of their out-of-pocket medical and hospital expenses.

Benefits and parts

Medicare has four parts: loosely speaking Part A is Hospital Insurance. Part B is Medical Services Insurance. Medicare Part D covers many prescription drugs, though some are covered by Part B. In general, the distinction is based on whether or not the drugs are self-administered but even this distinction is not total. Public Part C Medicare health plans, the most popular of which are branded Medicare Advantage, are another way for Original Medicare (Part A and B) beneficiaries to receive their Part A, B and D benefits; simply, Part C is capitated fee and Original Medicare is fee for service. All Medicare benefits are subject to medical necessity.

The original program included Parts A and B. Part-C-like plans have existed as demonstration projects in Medicare since the early 1970s, but the Part was formalized by 1997 legislation. Part D was enacted by 2003 legislation and introduced on January 1, 2006. Previously, coverage for self-administered prescription drugs (if desired) was obtained by private insurance or through a public Part C plan (or by one of its predecessor demonstration plans before enactment).

In April 2018, CMS began mailing out new Medicare cards with new ID numbers to all beneficiaries.[26] Previous cards had ID numbers containing beneficiaries' Social Security numbers; the new ID numbers are randomly generated and not tied to any other personally identifying information.[27][28]

Part A: Hospital/hospice insurance

Part A covers inpatient hospital stays where the beneficiary has been formally admitted to the hospital, including semi-private room, food, and tests. As of January 1, 2020, Medicare Part A had an inpatient hospital deductible of $1408, coinsurance per day as $352 after 61 days' confinement within one "spell of illness", coinsurance for "lifetime reserve days" (essentially, days 91–150 of one or more stay of more than 60 days) of $704 per day. The structure of coinsurance in a Skilled Nursing Facility (following a medically necessary hospital confinement of three nights in row or more) is different: zero for days 1–20; $167.50 per day for days 21–100. Many medical services provided under Part A (e.g., some surgery in an acute care hospital, some physical therapy in a skilled nursing facility) are covered under Part B. These coverage amounts increase or decrease yearly on the first day of the year.

The maximum length of stay that Medicare Part A covers in a hospital admitted inpatient stay or series of stays is typically 90 days. The first 60 days would be paid by Medicare in full, except one copay (also and more commonly referred to as a "deductible") at the beginning of the 60 days of $1340 as of 2018. Days 61–90 require a co-payment of $335 per day as of 2018. The beneficiary is also allocated "lifetime reserve days" that can be used after 90 days. These lifetime reserve days require a copayment of $670 per day as of 2018, and the beneficiary can only use a total of 60 of these days throughout their lifetime.[29] A new pool of 90 hospital days, with new copays of $1340 in 2018 and $335 per day for days 61–90, starts only after the beneficiary has 60 days continuously with no payment from Medicare for hospital or Skilled Nursing Facility confinement.[30]

Some "hospital services" are provided as inpatient services, which would be reimbursed under Part A; or as outpatient services, which would be reimbursed, not under Part A, but under Part B instead. The "Two-Midnight Rule" decides which is which. In August 2013, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced a final rule concerning eligibility for hospital inpatient services effective October 1, 2013. Under the new rule, if a physician admits a Medicare beneficiary as an inpatient with an expectation that the patient will require hospital care that "crosses two midnights", Medicare Part A payment is "generally appropriate". However, if it is anticipated that the patient will require hospital care for less than two midnights, Medicare Part A payment is generally not appropriate; payment such as is approved will be paid under Part B.[31] The time a patient spends in the hospital before an inpatient admission is formally ordered is considered outpatient time. But, hospitals and physicians can take into consideration the pre-inpatient admission time when determining if a patient's care will reasonably be expected to cross two midnights to be covered under Part A.[32] In addition to deciding which trust fund is used to pay for these various outpatient versus inpatient charges, the number of days for which a person is formally considered an admitted patient affects eligibility for Part A skilled nursing services.

Medicare penalizes hospitals for readmissions. After making initial payments for hospital stays, Medicare will take back from the hospital these payments, plus a penalty of 4 to 18 times the initial payment, if an above-average number of patients from the hospital are readmitted within 30 days. These readmission penalties apply after some of the most common treatments: pneumonia, heart failure, heart attack, COPD, knee replacement, hip replacement.[33][34] A study of 18 states conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) found that 1.8 million Medicare patients aged 65 and older were readmitted within 30 days of an initial hospital stay in 2011; the conditions with the highest readmission rates were congestive heart failure, sepsis, pneumonia, and COPD and bronchiectasis.[35]

The highest penalties on hospitals are charged after knee or hip replacements, $265,000 per excess readmission.[36] The goals are to encourage better post-hospital care and more referrals to hospice and end-of-life care in lieu of treatment,[37][38] while the effect is also to reduce coverage in hospitals that treat poor and frail patients.[39][40] The total penalties for above-average readmissions in 2013 are $280 million,[41] for 7,000 excess readmissions, or $40,000 for each readmission above the US average rate.[42]

Part A fully covers brief stays for rehabilitation or convalescence in a skilled nursing facility and up to 100 days per medical necessity with a co-pay if certain criteria are met:[43]

- A preceding hospital stay must be at least three days as an inpatient, three midnights, not counting the discharge date.

- The skilled nursing facility stay must be for something diagnosed during the hospital stay or for the main cause of hospital stay.

- If the patient is not receiving rehabilitation but has some other ailment that requires skilled nursing supervision (e.g., wound management) then the nursing home stay would be covered.

- The care being rendered by the nursing home must be skilled. Medicare part A does not pay for stays that only provide custodial, non-skilled, or long-term care activities, including activities of daily living (ADL) such as personal hygiene, cooking, cleaning, etc.

- The care must be medically necessary and progress against some set plan must be made on some schedule determined by a doctor.

The first 20 days would be paid for in full by Medicare with the remaining 80 days requiring a co-payment of $167.50 per day as of 2018. Many insurance group retiree, Medigap and Part C insurance plans have a provision for additional coverage of skilled nursing care in the indemnity insurance policies they sell or health plans they sponsor. If a beneficiary uses some portion of their Part A benefit and then goes at least 60 days without receiving facility-based skilled services, the 90-day hospital clock and 100-day nursing home clock are reset and the person qualifies for new benefit periods.

Hospice benefits are also provided under Part A of Medicare for terminally ill persons with less than six months to live, as determined by the patient's physician. The terminally ill person must sign a statement that hospice care has been chosen over other Medicare-covered benefits, (e.g. assisted living or hospital care).[44] Treatment provided includes pharmaceutical products for symptom control and pain relief as well as other services not otherwise covered by Medicare such as grief counseling. Hospice is covered 100% with no co-pay or deductible by Medicare Part A except that patients are responsible for a copay for outpatient drugs and respite care, if needed.[45]

Part B: Medical insurance

Part B medical insurance helps pay for some services and products not covered by Part A, generally on an outpatient basis (but can also apply to acute care settings per physician designated observation status at a hospital). Part B is optional. It is often deferred if the beneficiary or his/her spouse is still working and has group health coverage through that employer. There is a lifetime penalty (10% per year on the premium) imposed for not enrolling in Part B when first eligible.

Part B coverage begins once a patient meets his or her deductible ($183 for 2017), then typically Medicare covers 80% of the RUC-set rate for approved services, while the remaining 20% is the responsibility of the patient,[46] either directly or indirectly by private group retiree or Medigap insurance. Part B coverage covers 100% for preventive services such as yearly mammogram screenings, osteoporosis screening, and many other preventive screenings.

Part B coverage includes outpatient physician services, visiting nurse, and other services such as x-rays, laboratory and diagnostic tests, influenza and pneumonia vaccinations, blood transfusions, renal dialysis, outpatient hospital procedures, limited ambulance transportation, immunosuppressive drugs for organ transplant recipients, chemotherapy, hormonal treatments such as Lupron, and other outpatient medical treatments administered in a doctor's office. It also includes chiropractic care. Medication administration is covered under Part B if it is administered by the physician during an office visit. No prior authorization is required for any services rendered.

Part B also helps with durable medical equipment (DME), including but not limited to canes, walkers, lift chairs, wheelchairs, and mobility scooters for those with mobility impairments. Prosthetic devices such as artificial limbs and breast prosthesis following mastectomy, as well as one pair of eyeglasses following cataract surgery, and oxygen for home use are also covered.[47]

Complex rules control Part B benefits, and periodically issued advisories describe coverage criteria. On the national level these advisories are issued by CMS, and are known as National Coverage Determinations (NCD). Local Coverage Determinations (LCD) apply within the multi-state area managed by a specific regional Medicare Part B contractor (which is an insurance company), and Local Medical Review Policies (LMRP) were superseded by LCDs in 2003. Coverage information is also located in the CMS Internet-Only Manuals (IOM), the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), the Social Security Act, and the Federal Register.

The Monthly Premium for Part B for 2019 is $135.50 per month but anyone on Social Security in 2019 is "held harmless" from that amount if the increase in their SS monthly benefit does not cover the increase in their Part B premium from 2019 to 2020. This hold harmless provision is significant in years when SS does not increase but that is not the case for 2020. There are additional income-weighted surtaxes for those with incomes more than $85,000 per annum.[48]

Part C: Medicare Advantage plans

With the passage of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Medicare beneficiaries were formally given the option to receive their Original Medicare benefits through capitated health insurance Part C health plans, instead of through the Original fee for service Medicare payment system. Many had previously had that option via a series of demonstration projects that dated back to the early 1970s. These Part C plans were initially known in 1997 as "Medicare+Choice". As of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, most "Medicare+Choice" plans were re-branded as "Medicare Advantage" (MA) plans (though MA is a government term and might not even be "visible" to the Part C health plan beneficiary). Other plan types, such as 1876 Cost plans, are also available in limited areas of the country. Cost plans are not Medicare Advantage plans and are not capitated. Instead, beneficiaries keep their Original Medicare benefits while their sponsor administers their Part A and Part B benefits. The sponsor of a Part C plan could be an integrated health delivery system or spin-out, a union, a religious organization, an insurance company or other type of organization.

Public Part C Medicare Advantage and other Part C health plans are required to offer coverage that meets or exceeds the standards set by Original Medicare but they do not have to cover every benefit in the same way (the plan must be actuarially equivalent to Original Medicare benefits). After approval by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, if a Part C plan chooses to cover less than Original Medicare for some benefits, such as Skilled Nursing Facility care, the savings may be passed along to consumers by offering even lower co-payments for doctor visits (or any other plus or minus aggregation approved by CMS).[49]

Original "fee-for-service" Medicare Parts A and B have a standard benefit package that covers medically necessary care as described in the sections above that members can receive from nearly any hospital or doctor in the country (if that doctor or hospital accepts Medicare). Original Medicare beneficiaries who choose to enroll in a Part C Medicare Advantage or other Part C health plan instead give up none of their rights as an Original Medicare beneficiary, receive the same standard benefits—as a minimum—as provided in Original Medicare, and get an annual out of pocket (OOP) upper spending limit not included in Original Medicare. However, they must typically use only a select network of providers except in emergencies or for urgent care while travelling, typically restricted to the area surrounding their legal residence (which can vary from tens to over 100 miles depending on county). Most Part C plans are traditional health maintenance organizations (HMOs) that require the patient to have a primary care physician, though others are preferred provider organizations (which typically means the provider restrictions are not as confining as with an HMO). Others are hybrids of HMO and PPO called HMO-POS (for point of service) and a few public Part C health plans are actually fee-for-service hybrids.

Public Part C Medicare Advantage health plan members typically also pay a monthly premium in addition to the Medicare Part B premium to cover items not covered by traditional Medicare (Parts A & B), such as the OOP limit, self-administered prescription drugs, dental care, vision care, annual physicals, coverage outside the United States, and even gym or health club memberships as well as—and probably most importantly—reduce the 20% co-pays and high deductibles associated with Original Medicare.[50] But in some situations the benefits are more limited (but they can never be more limited than Original Medicare and must always include an OOP limit) and there is no premium. The OOP limit can be as low as $1500 and as high as but no higher than $6700. In some cases, the sponsor even rebates part or all of the Part B premium, though these types of Part C plans are becoming rare.

Before 2003 Part C plans tended to be suburban HMOs tied to major nearby teaching hospitals that cost the government the same as or even 5% less on average than it cost to cover the medical needs of a comparable beneficiary on Original Medicare. The 2003-law payment framework/bidding/rebate formulas overcompensated some Part C plan sponsors by 7 percent (2009) on average nationally compared to what Original Medicare beneficiaries cost per person on average nationally that year and as much as 5 percent (2016) less nationally in other years (see any recent year's Medicare Trustees Report, Table II.B.1).

The 2003 payment formulas succeeded in increasing the percentage of rural and inner-city poor that could take advantage of the OOP limit and lower co-pays and deductibles—as well as the coordinated medical care—associated with Part C plans. In practice, however, one set of Medicare beneficiaries received more benefits than others. The MedPAC Congressional advisory group found in one year the comparative difference for "like beneficiaries" was as high as 14% and have tended to average about 2% higher.[51] The word "like" in the previous sentence is key. MedPAC does not include all beneficiaries in its comparisons and MedPAC will not define what it means by "like" but it apparently includes people who are only on Part A, which severely skews its percentage comparisons—see January 2017 MedPAC meeting presentations. The differences caused by the 2003-law payment formulas were almost completely eliminated by PPACA and have been almost totally phased out according to the 2018 MedPAC annual report, March 2018. One remaining special-payment-formula program—designed primarily for unions wishing to sponsor a Part C plan—is being phased out beginning in 2017. In 2013 and since, on average a Part C beneficiary cost the Medicare Trust Funds 2-5% less than a beneficiary on traditional fee for service Medicare, completely reversing the situation in 2006-2009 right after implementation of the 2003 law and restoring the capitated fee vs fee for service funding balance to its original intended parity level.

The intention of both the 1997 and 2003 law was that the differences between fee for service and capitated fee beneficiaries would reach parity over time and that has mostly been achieved, given that it can never literally be achieved without a major reform of Medicare because the Part C capitated fee in one year is based on the fee for service spending the previous year.

Enrollment in public Part C health plans, including Medicare Advantage plans, grew from about 1% of total Medicare enrollment in 1997 when the law was passed (the 1% representing people on pre-law demonstration programs) to about 37% in 2019. The absolute number of beneficiaries on Part C has increased even more dramatically on a percentage basis because of the large increase of people on Original Medicare since 1997. Almost all Medicare beneficiaries have access to at least two public Medicare Part C plans; most have access to three or more.

Part D: Prescription drug plans

Medicare Part D went into effect on January 1, 2006. Anyone with Part A or B is eligible for Part D, which covers mostly self-administered drugs. It was made possible by the passage of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003. To receive this benefit, a person with Medicare must enroll in a stand-alone Prescription Drug Plan (PDP) or public Part C health plan with integrated prescription drug coverage (MA-PD). These plans are approved and regulated by the Medicare program, but are actually designed and administered by various sponsors including charities, integrated health delivery systems, unions and health insurance companies; almost all these sponsors in turn use pharmacy benefit managers in the same way as they are used by sponsors of health insurance for those not on Medicare. Unlike Original Medicare (Part A and B), Part D coverage is not standardized (though it is highly regulated by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services). Plans choose which drugs they wish to cover (but must cover at least two drugs in 148 different categories and cover all or "substantially all" drugs in the following protected classes of drugs: anti-cancer; anti-psychotic; anti-convulsant, anti-depressants, immuno-suppressant, and HIV and AIDS drugs). The plans can also specify with CMS approval at what level (or tier) they wish to cover it, and are encouraged to use step therapy. Some drugs are excluded from coverage altogether and Part D plans that cover excluded drugs are not allowed to pass those costs on to Medicare, and plans are required to repay CMS if they are found to have billed Medicare in these cases.[52]

Under the 2003 law that created Medicare Part D, the Social Security Administration offers an Extra Help program to lower-income seniors such that they have almost no drug costs; in addition, approximately 25 states offer additional assistance on top of Part D. For beneficiaries who are dual-eligible (Medicare and Medicaid eligible) Medicaid may pay for drugs not covered by Part D of Medicare. Most of this aid to lower-income seniors was available to them through other programs before Part D was implemented.

Coverage by beneficiary spending is broken up into four phases: deductible, initial spend, gap (infamously called the "donut hole"), and catastrophic. Under a CMS template, there is usually a $100 or so deductible before benefits commence (maximum of $415 in 2019) followed by the initial spend phase where the templated co-pay is 25%, followed by gap phase (where originally the templated co-pay was 100% but that will fall to 25% in 2020 for all drugs), followed by the catastrophic phase with a templated co-pay of about 5%. The beneficiaries' OOP spend amounts vary yearly but are approximately as of 2018 $1000 in the initial spend phase and $3000 to reach the catastrophic phase. This is just a template and about half of all Part D plans differ (for example, no initial deductible, better coverage in the gap) with permission of CMS, which it typically grants as long as the sponsor provides at least the actuarial equivalent value.

Out-of-pocket costs

No part of Medicare pays for all of a beneficiary's covered medical costs and many costs and services are not covered at all. The program contains premiums, deductibles and coinsurance, which the covered individual must pay out-of-pocket. A study published by the Kaiser Family Foundation in 2008 found the Fee-for-Service Medicare benefit package was less generous than either the typical large employer preferred provider organization plan or the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program Standard Option.[53] Some people may qualify to have other governmental programs (such as Medicaid) pay premiums and some or all of the costs associated with Medicare.

Premiums

Most Medicare enrollees do not pay a monthly Part A premium, because they (or a spouse) have had 40 or more 3-month quarters in which they paid Federal Insurance Contributions Act taxes. The benefit is the same no matter how much or how little the beneficiary paid as long as the minimum number of quarters is reached. Medicare-eligible persons who do not have 40 or more quarters of Medicare-covered employment may buy into Part A for an annual adjusted monthly premium of:

- $248.00 per month (as of 2012)[54] for those with 30–39 quarters of Medicare-covered employment, or

- $451.00 per month (as of 2012)[54] for those with fewer than 30 quarters of Medicare-covered employment and who are not otherwise eligible for premium-free Part A coverage.[55]

Most Medicare Part B enrollees pay an insurance premium for this coverage; the standard Part B premium for 2019 is $135.50 a month. A new income-based premium surtax schema has been in effect since 2007, wherein Part B premiums are higher for beneficiaries with incomes exceeding $85,000 for individuals or $170,000 for married couples. Depending on the extent to which beneficiary earnings exceed the base income, these higher Part B premiums are from 30% to 70% higher with the highest premium paid by individuals earning more than $214,000, or married couples earning more than $428,000.[56]

Medicare Part B premiums are commonly deducted automatically from beneficiaries' monthly Social Security deposits. They can also be paid quarterly via bill sent directly to beneficiaries or via deduction from a bank account. These alternatives are becoming more common because whereas the eligibility age for Medicare has remained at 65 per the 1965 legislation, the so-called Full Retirement Age for Social Security has been increased to over 66 and will go even higher over time. Therefore, many people delay collecting Social Security but join Medicare at 65 and have to pay their Part B premium directly.

If you have higher income, you will pay an additional premium amount for Medicare Part B and Medicare prescription drug coverage. The additional amount is called the income-related monthly adjustment amount (IRMAA).

- Part B: For most beneficiaries, the government pays a substantial portion—about 75 percent—of the Part B premium, and the beneficiary pays the remaining 25 percent. If you are a higher-income beneficiary, you will pay a larger percentage of the total cost of Part B based on the income you report to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). You will pay monthly Part B premiums equal to 35, 50, 65, 80, or 85 percent of the total cost, depending on what you report to the IRS (for 2020, that would be on your 2018 tax return).

- Part D: If you are a higher-income beneficiary with Medicare prescription drug coverage, you will pay monthly premiums plus an additional amount, which is based on what you report to the IRS (for 2020, that would be on your 2018 tax return).

| Adjusted Gross Income | Part B IRMAA | Part D IRMAA |

|---|---|---|

| $87,000.01–109,000.00 | $57.80 | $12.20 |

| $109,000.01–136,000.00 | $144.60 | $31.50 |

| $136,000.01–163,000.00 | $231.40 | $50.70 |

| $163,000.01–499,999.99 | $318.10 | $70.00 |

| More than $499,999.99 | $347.00 | $76.40 |

| Adjusted Gross Income | Part B IRMAA | Part D IRMAA |

|---|---|---|

| $174,000.01–218,000.00 | $57.80 | $12.20 |

| $218,000.01–272,000.00 | $144.60 | $31.50 |

| $272,000.01–326,000.00 | $231.40 | $50.70 |

| $326,000.01–749,999.99 | $318.10 | $70.00 |

| More than $749,999.99 | $347.00 | $76.40 |

| Adjusted Gross Income | Part B IRMAA | Part D IRMAA |

|---|---|---|

| $87,000.01–412,999.99 | $318.10 | $70.00 |

| More than $412,999.99 | $347.00 | $76.40 |

Part C plans may or may not charge premiums (almost all do), depending on the plans' designs as approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Part D premiums vary widely based on the benefit level.

Deductible and coinsurance

Part A—For each benefit period, a beneficiary pays an annually adjusted:

- A Part A deductible of $1,288 in 2016 and $1,316 in 2017 for a hospital stay of 1–60 days.[57]

- A $322 per day co-pay in 2016 and $329 co-pay in 2017 for days 61–90 of a hospital stay.[57]

- A $644 per day co-pay in 2016 and $658 co-pay in 2017 for days 91–150 of a hospital stay.,[57] as part of their limited Lifetime Reserve Days.

- All costs for each day beyond 150 days[57]

- Coinsurance for a Skilled Nursing Facility is $161 per day in 2016 and $164.50 in 2017 for days 21 through 100 for each benefit period (no co-pay for the first 20 days).[57]

- A blood deductible of the first 3 pints of blood needed in a calendar year, unless replaced. There is a 3-pint blood deductible for both Part A and Part B, and these separate deductibles do not overlap.

Part B—After beneficiaries meet the yearly deductible of $183.00 for 2017, they will be required to pay a co-insurance of 20% of the Medicare-approved amount for all services covered by Part B with the exception of most lab services, which are covered at 100%. Previously, outpatient mental health services was covered at 50%, but under the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008, it gradually decreased over several years and now matches the 20% required for other services.[58] They are also required to pay an excess charge of 15% for services rendered by physicians who do not accept assignment.

The deductibles, co-pays, and coinsurance charges for Part C and D plans vary from plan to plan. All Part C plans include an annual out-of-pocket (OOP) upper spend limit. Original Medicare does not include an OOP limit.

Medicare supplement (Medigap) policies

Of the Medicare beneficiaries who are not dual eligible for both Medicare (around 10% are fully dual eligible) and Medicaid or that do not receive group retirement insurance via a former employer (about 30%) or do not choose a public Part C Medicare health plan (about 35%) or who are not otherwise insured (about 5%—e.g., still working and receiving employer insurance, on VA, etc.), almost all the remaining elect to purchase a type of private supplemental indemnity insurance policy called a Medigap plan (about 20%), to help fill in the financial holes in Original Medicare (Part A and B) in addition to public Part D. Note that the percentages add up to over 100% because many beneficiaries have more than one type of additional protection on top of Original Medicare.

These Medigap insurance policies are standardized by CMS, but are sold and administered by private companies. Some Medigap policies sold before 2006 may include coverage for prescription drugs. Medigap policies sold after the introduction of Medicare Part D on January 1, 2006, are prohibited from covering drugs. Medicare regulations prohibit a Medicare beneficiary from being sold both a public Part C Medicare health plan and a private Medigap Policy. As with public Part C health plans, private Medigap policies are only available to beneficiaries who are already signed up for Original Medicare Part A and Part B. These policies are regulated by state insurance departments rather than the federal government although CMS outlines what the various Medigap plans must cover at a minimum. Therefore, the types and prices of Medigap policies vary widely from state to state and the degree of underwriting, discounts for new members, and open enrollment and guaranteed issue rules also vary widely from state to state.

As of 2016, 11 policies are currently sold—though few are available in all states, and some are not available at all in Massachusetts, Minnesota and Wisconsin (although these states have analogs to the lettered Medigap plans). These plans are standardized with a base and a series of riders. These are Plan A, Plan B, Plan C, Plan D, Plan F, High Deductible Plan F, Plan G, Plan K, Plan L, Plan M, and Plan N. Cost is usually the only difference between Medigap policies with the same letter sold by different insurance companies in the same state. Unlike public Part C Medicare health Plans, Medigap plans have no networks, and any provider who accepts Original Medicare must also accept Medigap.

All insurance companies that sell Medigap policies are required to make Plan A available, and if they offer any other policies, they must also make either Plan C or Plan F available as well, though Plan F is scheduled to sunset in the year 2020. Anyone who currently has a Plan F may keep it.[59] Many of the insurance companies that offer Medigap insurance policies also sponsor Part C health plans but most Part C health plans are sponsored by integrated health delivery systems and their spin-offs, charities, and unions as opposed to insurance companies.

Payment for services

Medicare contracts with regional insurance companies to process over one billion fee-for-service claims per year. In 2008, Medicare accounted for 13% ($386 billion) of the federal budget. In 2016 it is projected to account for close to 15% ($683 billion) of the total expenditures. For the decade 2010–2019 Medicare is projected to cost 6.4 trillion dollars.[60]

Reimbursement for Part A services

For institutional care, such as hospital and nursing home care, Medicare uses prospective payment systems. In a prospective payment system, the health care institution receives a set amount of money for each episode of care provided to a patient, regardless of the actual amount of care. The actual allotment of funds is based on a list of diagnosis-related groups (DRG). The actual amount depends on the primary diagnosis that is actually made at the hospital. There are some issues surrounding Medicare's use of DRGs because if the patient uses less care, the hospital gets to keep the remainder. This, in theory, should balance the costs for the hospital. However, if the patient uses more care, then the hospital has to cover its own losses. This results in the issue of "upcoding", when a physician makes a more severe diagnosis to hedge against accidental costs.[61]

Reimbursement for Part B services

Payment for physician services under Medicare has evolved since the program was created in 1965. Initially, Medicare compensated physicians based on the physician's charges, and allowed physicians to bill Medicare beneficiaries the amount in excess of Medicare's reimbursement. In 1975, annual increases in physician fees were limited by the Medicare Economic Index (MEI). The MEI was designed to measure changes in costs of physician's time and operating expenses, adjusted for changes in physician productivity. From 1984 to 1991, the yearly change in fees was determined by legislation. This was done because physician fees were rising faster than projected.

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989 made several changes to physician payments under Medicare. Firstly, it introduced the Medicare Fee Schedule, which took effect in 1992. Secondly, it limited the amount Medicare non-providers could balance bill Medicare beneficiaries. Thirdly, it introduced the Medicare Volume Performance Standards (MVPS) as a way to control costs.[62]

On January 1, 1992, Medicare introduced the Medicare Fee Schedule (MFS), a list of about 7,000 services that can be billed for. Each service is priced within the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) with three Relative Value Units (RVUs) values largely determining the price. The three RVUs for a procedure are each geographically weighted and the weighted RVU value is multiplied by a global Conversion Factor (CF), yielding a price in dollars. The RVUs themselves are largely decided by a private group of 29 (mostly specialist) physicians—the American Medical Association's Specialty Society Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC).[63]

From 1992 to 1997, adjustments to physician payments were adjusted using the MEI and the MVPS, which essentially tried to compensate for the increasing volume of services provided by physicians by decreasing their reimbursement per service.

In 1998, Congress replaced the VPS with the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR). This was done because of highly variable payment rates under the MVPS. The SGR attempts to control spending by setting yearly and cumulative spending targets. If actual spending for a given year exceeds the spending target for that year, reimbursement rates are adjusted downward by decreasing the Conversion Factor (CF) for RBRVS RVUs.

In 2002, payment rates were cut by 4.8%. In 2003, payment rates were scheduled to be reduced by 4.4%. However, Congress boosted the cumulative SGR target in the Consolidated Appropriation Resolution of 2003 (P.L. 108–7), allowing payments for physician services to rise 1.6%. In 2004 and 2005, payment rates were again scheduled to be reduced. The Medicare Modernization Act (P.L. 108–173) increased payments by 1.5% for those two years.

In 2006, the SGR mechanism was scheduled to decrease physician payments by 4.4%. (This number results from a 7% decrease in physician payments times a 2.8% inflation adjustment increase.) Congress overrode this decrease in the Deficit Reduction Act (P.L. 109–362), and held physician payments in 2006 at their 2005 levels. Similarly, another congressional act held 2007 payments at their 2006 levels, and HR 6331 held 2008 physician payments to their 2007 levels, and provided for a 1.1% increase in physician payments in 2009. Without further continuing congressional intervention, the SGR is expected to decrease physician payments from 25% to 35% over the next several years.

MFS has been criticized for not paying doctors enough because of the low conversion factor. By adjustments to the MFS conversion factor, it is possible to make global adjustments in payments to all doctors.[64]

The SGR was the subject of possible reform legislation again in 2014. On March 14, 2014, the United States House of Representatives passed the SGR Repeal and Medicare Provider Payment Modernization Act of 2014 (H.R. 4015; 113th Congress), a bill that would have replaced the (SGR) formula with new systems for establishing those payment rates.[65] However, the bill would pay for these changes by delaying the Affordable Care Act's individual mandate requirement, a proposal that was very unpopular with Democrats.[66] The SGR was expected to cause Medicare reimbursement cuts of 24 percent on April 1, 2014, if a solution to reform or delay the SGR was not found.[67] This led to another bill, the Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 (H.R. 4302; 113th Congress), which would delay those cuts until March 2015.[67] This bill was also controversial. The American Medical Association and other medical groups opposed it, asking Congress to provide a permanent solution instead of just another delay.[68]

The SGR process was replaced by new rules as of the passage of MACRA in 2015.

Provider participation

There are two ways for providers to be reimbursed in Medicare. "Participating" providers accept "assignment", which means that they accept Medicare's approved rate for their services as payment (typically 80% from Medicare and 20% from the beneficiary). Some non-participating doctors do not take assignment, but they also treat Medicare enrollees and are authorized to balance bills no more than a small fixed amount above Medicare's approved rate. A minority of doctors are "private contractors" from a Medicare perspective, which means they opt out of Medicare and refuse to accept Medicare payments altogether. These doctors are required to inform patients that they will be liable for the full cost of their services out-of-pocket, often in advance of treatment.[69]

While the majority of providers accept Medicare assignments, (97 percent for some specialties),[70] and most physicians still accept at least some new Medicare patients, that number is in decline.[71] While 80% of physicians in the Texas Medical Association accepted new Medicare patients in 2000, only 60% were doing so by 2012.[72] A study published in 2012 concluded that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) relies on the recommendations of an American Medical Association advisory panel. The study led by Dr. Miriam J. Laugesen, of Columbia Mailman School of Public Health, and colleagues at UCLA and the University of Illinois, shows that for services provided between 1994 and 2010, CMS agreed with 87.4% of the recommendations of the committee, known as RUC or the Relative Value Update Committee.[73]

Office medication reimbursement

Chemotherapy and other medications dispensed in a physician's office are reimbursed according to the Average Sales Price (ASP),[74] a number computed by taking the total dollar sales of a drug as the numerator and the number of units sold nationwide as the denominator.[75] The current reimbursement formula is known as "ASP+6" since it reimburses physicians at 106% of the ASP of drugs. Pharmaceutical company discounts and rebates are included in the calculation of ASP, and tend to reduce it. In addition, Medicare pays 80% of ASP+6, which is the equivalent of 84.8% of the actual average cost of the drug. Some patients have supplemental insurance or can afford the co-pay. Large numbers do not. This leaves the payment to physicians for most of the drugs in an "underwater" state. ASP+6 superseded Average Wholesale Price in 2005,[76] after a 2003 front-page New York Times article drew attention to the inaccuracies of Average Wholesale Price calculations.[77]

This procedure is scheduled to change dramatically in 2017 under a CMS proposal that will likely be finalized in October 2016.

Medicare 10 percent incentive payments

"Physicians in geographic Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) and Physician Scarcity Areas (PSAs) can receive incentive payments from Medicare. Payments are made on a quarterly basis, rather than claim-by-claim, and are handled by each area's Medicare carrier."[78][79]

Enrollment

Generally, if an individual already receives Social Security payments, at age 65 the individual becomes automatically enrolled in Medicare Part A (Hospital Insurance) and Medicare Part B (Medical Insurance). If the individual chooses not to enroll in Part B (typically because the individual is still working and receiving employer insurance), then the individual must proactively opt out of it when receiving the automatic enrollment package. Delay in enrollment in Part B carries no penalty if the individual has other insurance (e.g. the employment situation noted above), but may be penalized under other circumstances. An individual who does not receive Social Security benefits upon turning 65 must sign up for Medicare if they want it. Penalties may apply if the individual chooses not to enroll at age 65 and does not have other insurance.

Part A Late Enrollment Penalty

If an individual is not eligible for premium-free Part A, and they do not buy a premium-based Part A when they are first eligible, the monthly premium may go up 10%.[80] The individual must pay the higher premium for twice the number of years that they could have had Part A, but did not sign up. For example, if they were eligible for Part A for two years but did not sign up, they must pay the higher premium for four years. Usually, individuals do not have to pay a penalty if they meet certain conditions that allow them to sign up for Part A during a Special Enrollment Period.

Part B Late Enrollment Penalty

If an individual does not sign up for Part B when they are first eligible, they may have to pay a late enrollment penalty for as long as they have Medicare. Their monthly premium for Part B may go up 10% for each full 12-month period that they could have had Part B, but did not sign up for it. Usually, they do not pay a late enrollment penalty if they meet certain conditions that allow them to sign up for Part B during a special enrollment period.[81]

Comparison with private insurance

Medicare differs from private insurance available to working Americans in that it is a social insurance program. Social insurance programs provide statutorily guaranteed benefits to the entire population (under certain circumstances, such as old age or unemployment). These benefits are financed in significant part through universal taxes. In effect, Medicare is a mechanism by which the state takes a portion of its citizens' resources to provide health and financial security to its citizens in old age or in case of disability, helping them cope with the cost of health care. In its universality, Medicare differs substantially from private insurers, which decide whom to cover and what benefits to offer to manage their risk pools and ensure that their costs do not exceed premiums.

Because the federal government is legally obligated to provide Medicare benefits to older and some disabled Americans, it cannot cut costs by restricting eligibility or benefits, except by going through a difficult legislative process, or by revising its interpretation of medical necessity. By statute, Medicare may only pay for items and services that are "reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member", unless there is another statutory authorization for payment.[82] Cutting costs by cutting benefits is difficult, but the program can also achieve substantial economies of scale in the prices it pays for health care and administrative expenses—and, as a result, private insurers' costs have grown almost 60% more than Medicare's since 1970.[83] Medicare's cost growth is now the same as GDP growth and expected to stay well below private insurance's for the next decade.[84]

Because Medicare offers statutorily determined benefits, its coverage policies and payment rates are publicly known, and all enrollees are entitled to the same coverage. In the private insurance market, plans can be tailored to offer different benefits to different customers, enabling individuals to reduce coverage costs while assuming risks for care that is not covered. Insurers, however, have far fewer disclosure requirements than Medicare, and studies show that customers in the private sector can find it difficult to know what their policy covers,[85] and at what cost.[86] Moreover, since Medicare collects data about utilization and costs for its enrollees—data that private insurers treat as trade secrets—it gives researchers key information about health care system performance.

Medicare also has an important role in driving changes in the entire health care system. Because Medicare pays for a huge share of health care in every region of the country, it has a great deal of power to set delivery and payment policies. For example, Medicare promoted the adaptation of prospective payments based on DRG's, which prevents unscrupulous providers from setting their own exorbitant prices.[87] Meanwhile, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has given Medicare the mandate to promote cost-containment throughout the health care system, for example, by promoting the creation of accountable care organizations or by replacing fee-for-service payments with bundled payments.[88]

Costs and funding challenges

.png.webp)

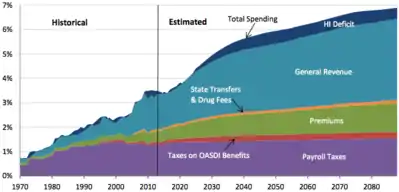

Over the long-term, Medicare faces significant financial challenges because of rising overall health care costs, increasing enrollment as the population ages, and a decreasing ratio of workers to enrollees. Total Medicare spending is projected to increase from $523 billion in 2010 to around $900 billion by 2020. From 2010 to 2030, Medicare enrollment is projected to increase dramatically, from 47 million to 79 million, and the ratio of workers to enrollees is expected to decrease from 3.7 to 2.4.[89] However, the ratio of workers to retirees has declined steadily for decades, and social insurance systems have remained sustainable due to rising worker productivity. There is some evidence that productivity gains will continue to offset demographic trends in the near future.[90]

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) wrote in 2008 that "future growth in spending per beneficiary for Medicare and Medicaid—the federal government's major health care programs—will be the most important determinant of long-term trends in federal spending. Changing those programs in ways that reduce the growth of costs—which will be difficult, in part because of the complexity of health policy choices—is ultimately the nation's central long-term challenge in setting federal fiscal policy."[91]

Overall health care costs were projected in 2011 to increase by 5.8 percent annually from 2010 to 2020, in part because of increased utilization of medical services, higher prices for services, and new technologies.[92] Health care costs are rising across the board, but the cost of insurance has risen dramatically for families and employers as well as the federal government. In fact, since 1970 the per-capita cost of private coverage has grown roughly one percentage point faster each year than the per-capita cost of Medicare. Since the late 1990s, Medicare has performed especially well relative to private insurers.[93] Over the next decade, Medicare's per capita spending is projected to grow at a rate of 2.5 percent each year, compared to private insurance's 4.8 percent.[94] Nonetheless, most experts and policymakers agree containing health care costs is essential to the nation's fiscal outlook. Much of the debate over the future of Medicare revolves around whether per capita costs should be reduced by limiting payments to providers or by shifting more costs to Medicare enrollees.

Indicators

Several measures serve as indicators of the long-term financial status of Medicare. These include total Medicare spending as a share of gross domestic product (GDP), the solvency of the Medicare HI trust fund, Medicare per-capita spending growth relative to inflation and per-capita GDP growth; general fund revenue as a share of total Medicare spending; and actuarial estimates of unfunded liability over the 75-year timeframe and the infinite horizon (netting expected premium/tax revenue against expected costs). The major issue in all these indicators is comparing any future projections against current law vs. what the actuaries expect to happen. For example, current law specifies that Part A payments to hospitals and skilled nursing facilities will be cut substantially after 2028 and that doctors will get no raises after 2025. The actuaries expect that the law will change to keep these events from happening.

Total Medicare spending as a share of GDP

This measure, which examines Medicare spending in the context of the US economy as a whole, is projected to increase from 3.7 percent in 2017 to 6.2 percent by 2092[94] under current law and over 9 percent under what the actuaries really expect will happen (called an "illustrative example" in recent-year Trustees Reports).

The solvency of the Medicare HI trust fund

This measure involves only Part A. The trust fund is considered insolvent when available revenue plus any existing balances will not cover 100 percent of annual projected costs. According to the latest estimate by the Medicare trustees (2018), the trust fund is expected to become insolvent in 8 years (2026), at which time available revenue will cover around 85 percent of annual projected costs for Part A services.[95] Since Medicare began, this solvency projection has ranged from two to 28 years, with an average of 11.3 years.[96] This and other projections in Medicare Trustees reports are based on what its actuaries call intermediate scenario but the reports also include worst-case and best-case projections that are quite different (other scenarios presume Congress will change present law).

Medicare per-capita spending growth relative to inflation and per-capita GDP growth

Per capita spending relative to inflation per-capita GDP growth was to be an important factor used by the PPACA-specified Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB), as a measure to determine whether it must recommend to Congress proposals to reduce Medicare costs. However, the IPAB never formed and was formally repealed by the Balanced Budget Act of 2018.

General fund revenue as a share of total Medicare spending

This measure, established under the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA), examines Medicare spending in the context of the federal budget. Each year, MMA requires the Medicare trustees to make a determination about whether general fund revenue is projected to exceed 45 percent of total program spending within a seven-year period. If the Medicare trustees make this determination in two consecutive years, a "funding warning" is issued. In response, the president must submit cost-saving legislation to Congress, which must consider this legislation on an expedited basis. This threshold was reached and a warning issued every year between 2006 and 2013 but it has not been reached since that time and is not expected to be reached in the 2016–2022 "window". This is a reflection of the reduced spending growth mandated by the ACA according to the Trustees.

Unfunded obligation

Medicare's unfunded obligation is the total amount of money that would have to be set aside today such that the principal and interest would cover the gap between projected revenues (mostly Part B premiums and Part A payroll taxes to be paid over the timeframe under current law) and spending over a given timeframe. By law the timeframe used is 75 years though the Medicare actuaries also give an infinite-horizon estimate because life expectancy consistently increases and other economic factors underlying the estimates change.

As of January 1, 2016, Medicare's unfunded obligation over the 75-year time frame is $3.8 trillion for the Part A Trust Fund and $28.6 trillion for Part B. Over an infinite timeframe the combined unfunded liability for both programs combined is over $50 trillion, with the difference primarily in the Part B estimate.[95][97] These estimates assume that CMS will pay full benefits as currently specified over those periods though that would be contrary to current United States law. In addition, as discussed throughout each annual Trustees' report, "the Medicare projections shown could be substantially understated as a result of other potentially unsustainable elements of current law." For example, current law effectively provides no raises for doctors after 2025; that is unlikely to happen. It is impossible for actuaries to estimate unfunded liability other than assuming current law is followed (except relative to benefits as noted), the Trustees state "that actual long-range present values for (Part A) expenditures and (Part B/D) expenditures and revenues could exceed the amounts estimated by a substantial margin."

Public opinion

Popular opinion surveys show that the public views Medicare's problems as serious, but not as urgent as other concerns. In January 2006, the Pew Research Center found 62 percent of the public said addressing Medicare's financial problems should be a high priority for the government, but that still put it behind other priorities.[98] Surveys suggest that there's no public consensus behind any specific strategy to keep the program solvent.[99]

Criticism

Robert M. Ball, a former commissioner of Social Security under President Kennedy in 1961 (and later under Johnson, and Nixon) defined the major obstacle to financing health insurance for the elderly: the high cost of care for the aged combined with the generally low incomes of retired people. Because retired older people use much more medical care than younger employed people, an insurance premium related to the risk for older people needed to be high, but if the high premium had to be paid after retirement, when incomes are low, it was an almost impossible burden for the average person. The only feasible approach, he said, was to finance health insurance in the same way as cash benefits for retirement, by contributions paid while at work, when the payments are least burdensome, with the protection furnished in retirement without further payment.[104] In the early 1960s relatively few of the elderly had health insurance, and what they had was usually inadequate. Insurers such as Blue Cross, which had originally applied the principle of community rating, faced competition from other commercial insurers that did not community rate, and so were forced to raise their rates for the elderly.[105]

Medicare is not generally an unearned entitlement. Entitlement is most commonly based on a record of contributions to the Medicare fund. As such it is a form of social insurance making it feasible for people to pay for insurance for sickness in old age when they are young and able to work and be assured of getting back benefits when they are older and no longer working. Some people will pay in more than they receive back and others will receive more benefits than they paid in. Unlike private insurance where some amount must be paid to attain coverage, all eligible persons can receive coverage regardless of how much or if they had ever paid in.

Politicized payment

Bruce Vladeck, director of the Health Care Financing Administration in the Clinton administration, has argued that lobbyists have changed the Medicare program "from one that provides a legal entitlement to beneficiaries to one that provides a de facto political entitlement to providers."[106]

Quality of beneficiary services

A 2001 study by the Government Accountability Office evaluated the quality of responses given by Medicare contractor customer service representatives to provider (physician) questions. The evaluators assembled a list of questions, which they asked during a random sampling of calls to Medicare contractors. The rate of complete, accurate information provided by Medicare customer service representatives was 15%.[107] Since then, steps have been taken to improve the quality of customer service given by Medicare contractors, specifically the 1-800-MEDICARE contractor. As a result, 1-800-MEDICARE customer service representatives (CSR) have seen an increase in training, quality assurance monitoring has significantly increased, and a customer satisfaction survey is offered to random callers.

Hospital accreditation

In most states the Joint Commission, a private, non-profit organization for accrediting hospitals, decides whether or not a hospital is able to participate in Medicare, as currently there are no competitor organizations recognized by CMS.

Other organizations can also accredit hospitals for Medicare. These include the Community Health Accreditation Program, the Accreditation Commission for Health Care, the Compliance Team and the Healthcare Quality Association on Accreditation.

Accreditation is voluntary and an organization may choose to be evaluated by their State Survey Agency or by CMS directly.[108]

Graduate medical education

Medicare funds the vast majority of residency training in the US. This tax-based financing covers resident salaries and benefits through payments called Direct Medical Education payments. Medicare also uses taxes for Indirect Medical Education, a subsidy paid to teaching hospitals in exchange for training resident physicians.[109] For the 2008 fiscal year these payments were $2.7 billion and $5.7 billion, respectively.[110] Overall funding levels have remained at the same level since 1996, so that the same number or fewer residents have been trained under this program.[111] Meanwhile, the US population continues to grow both older and larger, which has led to greater demand for physicians, in part due to higher rates of illness and disease among the elderly compared to younger individuals. At the same time the cost of medical services continue rising rapidly and many geographic areas face physician shortages, both trends suggesting the supply of physicians remains too low.[112]

Medicare thus finds itself in the odd position of having assumed control of the single largest funding source for graduate medical education, currently facing major budget constraints, and as a result, freezing funding for graduate medical education, as well as for physician reimbursement rates. This has forced hospitals to look for alternative sources of funding for residency slots.[111] This halt in funding in turn exacerbates the exact problem Medicare sought to solve in the first place: improving the availability of medical care. However, some healthcare administration experts believe that the shortage of physicians may be an opportunity for providers to reorganize their delivery systems to become less costly and more efficient. Physician assistants and Advanced Registered Nurse Practitioners may begin assuming more responsibilities that traditionally fell to doctors, but do not necessarily require the advanced training and skill of a physician.[113]

Legislation and reform

- 1960: PL 86-778 Social Security Amendments of 1960 (Kerr-Mills aid)

- 1965: PL 89-97 Social Security Act of 1965, Establishing Medicare Benefits[114]

- 1980: Medicare Secondary Payer Act of 1980, prescription drugs coverage added

- 1988: PL 100-360 Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of 1988[115][116]

- 1989: Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Repeal Act of 1989[115][116]

- 1997: PL 105-33 Balanced Budget Act of 1997

- 2003: PL 108-173 Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act

- 2010: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010

- 2013: Sequestration effects on Medicare due to Budget Control Act of 2011

- 2015: Extensive changes to Medicare, primarily to the SGR provisions of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 as part of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA)

- 2016: Changes to the Social Security "hold harmless" laws as they affect Part B premiums based on the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015

- 2022: Inflation Reduction Act included Medicare negotiation provisions, allowing negotiation of prescription drug prices beginning in 2026

In 1977, the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) was established as a federal agency responsible for the administration of Medicare and Medicaid. This would be renamed to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2001.[117] By 1983, the diagnosis-related group (DRG) replaced pay for service reimbursements to hospitals for Medicare patients.[118]

President Bill Clinton attempted an overhaul of Medicare through his health care reform plan in 1993–1994 but was unable to get the legislation passed by Congress.[119]

In 2003 Congress passed the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act, which President George W. Bush signed into law on December 8, 2003.[120] Part of this legislation included filling gaps in prescription-drug coverage left by the Medicare Secondary Payer Act that was enacted in 1980. The 2003 bill strengthened the Workers' Compensation Medicare Set-Aside Program (WCMSA) that is monitored and administered by CMS.

On August 1, 2007, the US House of Representatives voted to reduce payments to Medicare Advantage providers in order to pay for expanded coverage of children's health under the SCHIP program. As of 2008, Medicare Advantage plans cost, on average, 13 percent more per person insured for like beneficiaries than direct payment plans.[121] Many health economists have concluded that payments to Medicare Advantage providers have been excessive.[122][123] The Senate, after heavy lobbying from the insurance industry, declined to agree to the cuts in Medicare Advantage proposed by the House. President Bush subsequently vetoed the SCHIP extension.[124]

Effects of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act ("PPACA") of 2010 made a number of changes to the Medicare program. Several provisions of the law were designed to reduce the cost of Medicare. The most substantial provisions slowed the growth rate of payments to hospitals and skilled nursing facilities under Parts A of Medicare, through a variety of methods (e.g., arbitrary percentage cuts, penalties for readmissions).