Langerhans cell sarcoma

Langerhans cell sarcoma (LCS) is a rare form of malignant histiocytosis. It should not be confused with Langerhans cell histiocytosis, which is cytologically benign.[1] It can present most commonly in the skin and lymphatic tissue, but may also present in the lung, liver, and bone marrow.[2][3] Treatment is most commonly with surgery or chemotherapy.[3]

| Langerhans cell sarcoma | |

|---|---|

| |

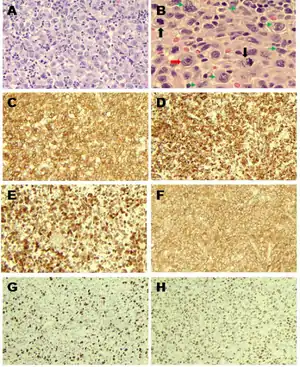

| Langerhans cell sarcoma as seen in this H&E stain | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

Classification

Dendritic cell neoplasms are classified by the World Health Organization as follows:[4]

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- Langerhans cell sarcoma

- Interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma/tumor

- Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma/tumor

- Dendritic cell sarcoma

Epidemiology

The exact incidence of LCS is unknown due to the rarity of the condition. The related condition, Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) is estimated to have an incidence of around 5 cases per 1 million people per year.[5] In one review of Japanese patients with confirmed LCS, patients were a median age of 41 years.[5] Patients were twice as likely to be female than male.[5] In another systematic review, the median age of presentation was 50 years, but with a slight predilection for males.[3]

Pathophysiology

Throughout the body in locations such as mucous membranes, skin, lymph nodes, thymus, and spleen are cells known as antigen-presenting cells. These cells are surveillance cells that take foreign antigens and present them to antigen-processing cells, such as T-cells, protecting the body from potential harm.[6][7] Antigen-presenting cells are also termed Dendritic cells, of which Langerhans cells are a subtype.[6] There are four main types that make up the structure and functions of lymphoid tissue, such as lymph nodes and splenic tissue.[4] By definition, Langerhans Cell Sarcoma (LCS) is a cancerous disease caused by the uncontrolled overproliferation of Langerhans cells.[5]

Because Langerhans cells are most commonly found in the mucosa and the skin, LCS is thought to usually begin here with further spread to other areas of the body via the lymphatic system.[3]

Langerhans cell sarcoma can occur de novo, or can occur as a malignant transformation of Langerhans cell histiocytosis.[3][8]

Clinical Manifestations

The related condition, LCH, presents with various clinical features depending on the bodily organs involved.[5] LCS shares most of these clinical presentations. Most commonly, these patients will present with generalized signs and symptoms such as fever and weight loss.[5] Blood tests will commonly show pancytopenia, an overall reduction in blood cell counts.[5] Additionally, these patients may display lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, skin lesions, bone lesions, and lung lesions.[5] Most common site presentations are the skin and lymphatics.[6][3] Other common sites of involvement include the lung, liver, and spleen.[3]

LCS will present with a varied gross appearance. When involving the skin, LCS will present as a patches of erythema, with nodules and ulceration present as well.[9] Skin lesions will most commonly involve the trunk, scalp, and legs.[9] Tumor size may range from 1-6 cm, but may be larger. Usually the tumor is well circumscribed with a surface covered in small nodules or protuberances. Most are of a solid consistency and are of a pink, white, or tan color. LCS tumors may present with much larger sizes and aggressive features, even causing some bleeding and necrosis of the surrounding tissue.[4]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Langerhans Cell Sarcoma is predominantly a pathologic diagnosis. Cells from these tumor samples will display features characteristic of Langerhans cells, but with additional signs of malignancy, such as increased mitoses, cellular atypia, and pleomorphic nuclei.[5]

CD-207 is a cellular marker associated with Birbeck granules than can be used for confirmation of cell type.[5] LCS will also stain positive for CD-68, CD-68R, CD-21, CD-35, S-100, CD1a, lysozyme, HLA-DR, CD4, fascin, Factor XIIIa, and cyclin D1, which are cellular markers typically used in the characterization of various pathology specimens.[4][5][6] Positive staining with CD1a and S-100 are required for diagnosis of LCS.[4] Positive staining with CD-207 (Langerin) is an additional confirmation marker of malignancy in LCS.[6][3][9] Other cellular markers have been reported to be positive in LCS, but have are not as routinely used.[5]

Histologically, Langerhans cells characteristically display Birbeck granules and nuclei with a longitudinal groove.[5][6] Birbeck granules are currently a poorly understood cellular structure, but are commonly used for cell-type identification.[10] Previously, the presence of Birbeck granules was necessary for diagnosis, but this is no longer considered diagnostic.[6]

Currently, there appears to be no relation of LCS with chromosomal abnormalities.[5]

The diagnosis of LCS can be difficult, especially due to its rarity. It has previously been mistaken with metastatic melanoma and metastatic large-cell carcinoma.[8]

Treatment

Treatment for this rare disease consists of a variety of approaches, with none displaying any increased efficacy over another.[4] There are currently three broad treatment strategies for LCS: surgery, chemotherapy, and combination with radiation therapy.[3] When the LCS tumor is readily accessible, the best treatment method is usually surgical removal.[4] There is, however, an observed increased risk of tumor relapse following surgical resection.[4] Both chemotherapy and radiation therapy are useful as treatments, either as monotherapy or in conjunction with other treatments.[6][3] Chemotherapy is currently the most common treatment method, either alone or in combination.[3] The most common chemotherapeutic regimen consisted of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (otherwise known as CHOP therapy).[3] Other common chemotherapeutic regimens include MAID (mesna, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and dacarbazine), ESHAP (etoposide, carboplatin, cytarabine, and methylprednisolone), EPIG (etoposide, cisplatin, ifosfamide, mesna, and gemcitabine), and AIM (doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and mesna).[8] Other regimens have been used with mixed levels of success.[3] In an effort to prevent recurrence, sometimes combination therapy is used. Following surgical resection, additional radiation therapy or chemotherapy may be performed to prevent relapse.[4] Patients receiving combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy has only shown limited benefit.[4]

There are a variety of other therapies under research with varying levels of reported success. These include high-dose chemotherapy, bone marrow transplants, and somatostatin analogues.[4][3]

When there is only one site of LCS involvement, monotherapy may be sufficient treatment. But when the disease has multiple sites or has metastasized, combination therapy will be necessary to achieve any level of adequate treatment.[6]

Prognosis

Overall prognosis of patients with LCS depends heavily on the bodily organ involved and the extent of involvement of the tumor.[5] Organs associated with a poor prognosis include the liver, lungs, and bone marrow.[5] In patients with a single site of involvement, survivability tends to be very favorable.[6] However, those with multi-organ involvement have a mortality rate of 50-66%.[5] One systematic review calculated the disease-specific survival as 27.2 months, or 58% at one year.[3] One group found the death rate to be 50% in patients with LCS, compared to 31% in patients who had the related condition LCH.[1] Survivability decreases dramatically with increased disease burden and spread.[3] LCS may be associated with other malignancies as well, such as follicular lymphoma, adenocarcinoma, and germ cell tumors.[4] Evidence of metastatic disease or relapse from a previously treated LCS usually signifies a worsened prognosis.[4] Treatment of these metastatic lesions or relapsed tumors may improve the patient's prognosis, but there is limited evidence as to a preferred therapy.[4]

See also

References

- Ronen S, Keiser E, Collins KM, Aung PP, Nagarajan P, Tetzlaff MT, et al. (April 2021). "Langerhans cell sarcoma involving skin and showing epidermotropism: A comprehensive review". Journal of Cutaneous Pathology. 48 (4): 547–557. doi:10.1111/cup.13803. PMID 32644218. S2CID 220435418.

- Jülg BD, Weidner S, Mayr D (March 2006). "Pulmonary manifestation of a Langerhans cell sarcoma: case report and review of the literature". Virchows Archiv. 448 (3): 369–374. doi:10.1007/s00428-005-0115-z. PMID 16328350. S2CID 32428348.

- Howard JE, Dwivedi RC, Masterson L, Jani P (April 2015). "Langerhans cell sarcoma: a systematic review". Cancer Treatment Reviews. 41 (4): 320–331. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.02.011. PMID 25805533.

- Kairouz S, Hashash J, Kabbara W, McHayleh W, Tabbara IA (October 2007). "Dendritic cell neoplasms: an overview". American Journal of Hematology. 82 (10): 924–928. doi:10.1002/ajh.20857. PMID 17636477. S2CID 30395885.

- Nakamine H, Yamakawa M, Yoshino T, Fukumoto T, Enomoto Y, Matsumura I (2016). "Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis and Langerhans Cell Sarcoma: Current Understanding and Differential Diagnosis". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hematopathology. 56 (2): 109–118. doi:10.3960/jslrt.56.109. PMC 6144204. PMID 27980300.

- Howard JE, Masterson L, Dwivedi RC, Jani P (March 2016). "Langerhans cell sarcoma of the head and neck". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 99: 180–188. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.12.017. PMID 26777877. S2CID 42032536.

- Zwerdling T, Won E, Shane L, Javahara R, Jaffe R (August 2014). "Langerhans cell sarcoma: case report and review of world literature". Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 36 (6): 419–425. doi:10.1097/MPH.0000000000000196. PMID 24942035. S2CID 12487003.

- Liu DT, Friesenbichler J, Holzer LA, Liegl-Atzwanger B, Beham-Schmid C, Leithner A (June 2016). "Langerhans cell sarcoma: a case report and review of the literature". Polish Journal of Pathology. 67 (2): 172–178. doi:10.5114/pjp.2016.61454. PMID 27543873.

- Lee JY, Jung KE, Kim HS, Lee JY, Kim HO, Park YM (February 2014). "Langerhans cell sarcoma: a case report and review of the literature". International Journal of Dermatology. 53 (2): e84–e87. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05668.x. PMID 23557341. S2CID 205399559.

- Mc Dermott R, Ziylan U, Spehner D, Bausinger H, Lipsker D, Mommaas M, et al. (January 2002). "Birbeck granules are subdomains of endosomal recycling compartment in human epidermal Langerhans cells, which form where Langerin accumulates". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 13 (1): 317–335. doi:10.1091/mbc.01-06-0300. PMC 65091. PMID 11809842.