Seattle & King County Emergency Medical Services System

The Seattle & King County Emergency Medical Services System is a fire-based two-tier response system providing prehospital basic and advanced life support services.

| Jurisdiction | 1.8 million |

|---|---|

| Dept. type | Fire-based two-tier response |

| BLS or ALS | 35 BLS, 6 ALS |

There are six paramedic provider programs in the system. The Seattle Fire Department operates Seattle Medic One. The program is funded by the city's general fund and has a different administrative structure than the five other Medic One programs.[1] The five other Medic One programs with the exception of King County Medic One are operated by fire departments under a formal contract with the EMS Division of Public Health - Seattle & King County.[2] King County Medic One is directly operated by the EMS Division.

The modern EMS system in King County began operation in 1970 with 15 paramedics staffing one paramedic unit in Seattle. In 2009, there were 255 paramedics[3] from six paramedic programs staffing 26 paramedic units.[4][5]

The system is a dynamic layered response system. An EMS response to an emergency begins with a telephone call to 9-1-1. Calls are transferred from a primary call taker to emergency medical call taker who gathers information from the caller, gives instructions to the caller, and determines what types of emergency personnel to send. For very serious and life-threatening emergencies firefighters trained in basic life support and paramedics trained in advanced life support respond simultaneously. Paramedics transport patients in critical condition. For less severe emergencies only firefighters will be dispatched. Basic life support personnel from either a fire department or private ambulance company transport non-critical patients.

History

.jpg.webp)

In 1968, motivated by the work of Frank Pantridge, cardiologist Leonard Cobb proposed to the chief of the Seattle Fire Department, Gordon Vickery, training firefighters to treat cardiac arrest. The department was attractive to Cobb because it already provided first aid and tracked its performance electronically.[6]

In 1969, they trained fifteen firefighters and used a grant from the Washington/Alaska Regional Medical Program to convert a large motor home into a Mobile Coronary Care Unit nicknamed "Moby Pig", which would respond to calls with both the firefighter paramedics and a physician on board.

The first Medic One call was on March 7, 1970. During the program's first year, 31 lives were saved.[7] The following year the program was changed, replacing the on-board doctors with fire department paramedics given advanced special training and remote access to the doctors.

In 1974, the TV news-magazine 60 Minutes profiled the success of Medic One, lauding the high standards of training and education provided by the Seattle training program. Correspondent Morley Safer declared, "If you have to have a heart attack, have it in Seattle". The phrase is still used frequently in conjunction with Medic One, due to its continued success which is reflected in the area's high survival rate for heart attacks and their comprehensive CPR training program.[8][9]

That same year Medic One incorporated as a privately held, non-profit organization and established the Medic One Foundation, which works on behalf of both fund raising and the expansion of the program. The program is financed by local property tax levies, which are voted on by the public every six years, along with private and corporate donations.[9]

Medic One had saved 655 patients from cardiac arrest by 1976 and this success was gaining national and international attention.[10] Medic One service was expanded into the rest of King County in 1976,[11] and in conjunction with the Medic One Foundation, other counties in Washington State began paramedic programs to serve their communities.

In 1979, Cobb and UW professor Mickey Eisenberg began training fire department emergency medical technician - Basics (EMT-Bs) to perform the administration of defibrillation for patients in cardiac arrest since the EMTs were usually at the patient's side several minutes before the paramedics. Eisenberg began training 9-1-1 dispatchers to provide instructions to lay-persons on how to perform CPR in 1982. With the introduction of automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) in 1984, EMTs were able to defibrillate patients in cardiac arrest even more quickly.[10]

Programs

There are five paramedic programs in the Medic One system.

| Paramedic program | Operated by | Paramedic units | Paramedics | Paramedic medical director | Service area(s) | Population served |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seattle Medic One | Seattle Fire Department | 7[4] | 78[4] | Michael Copass, MD[12] | Seattle | 600,000[13] |

| King County Medic One | Public Health - Seattle & King County | 9[5] | 77[13] | Tom Rea, MD[12] | Auburn, Black Diamond, Burien, Covington, Des Moines, Enumclaw, Federal Way, Kent, Maple Valley, Pacific, Renton, Seatac, Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, Skyway, Tukwila, Vashon, White Center[14] | 712,000[15] |

| Shoreline Medic One | Shoreline Fire Department | 3[5] | 29[16] | Gary Somers, MD[12] | Bothell, Shoreline[17] | 70,000[18] |

| Bellevue Medic One | Bellevue Fire Department | 4[5] | 36 | Jim Boehl, MD[12] | I-90 corridor, Bellevue, Mercer Island[17] | 140,000[19] |

| Redmond Medic One | Redmond Fire Department | 3[5] | 31 | Adrian Whorton, MD[12] | Duvall, Kirkland, Redmond, Woodinwille[17] | 104,000[20] |

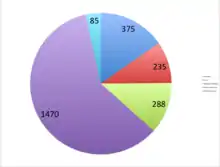

| Total | 26 | 251[3] | 1.8 million[21] |

Seattle Medic One

Seattle Medic One is the paramedic provider program serving Seattle. It is operated by the Seattle Fire Department. The paramedic medical director for Seattle Medic One is Michael Sayre. The Seattle program conducts field internships for the University of Washington Paramedic Training Program.[17]

King County Medic One

King County Medic One is the paramedic service serving all of South King County provided by Public Health - Seattle & King County.[17] Its medical director is Peter Kudenchuk.

Structure

Founded on strong physician leadership Medic One is structured around response, training, and quality improvement.

One of the primary components to the success of Medic One is their “Tiered Response System” which begins with the citizen call to the 9-1-1 center. Emergency Medical Dispatchers are trained to rapidly triage the call to dispatch the appropriate level of assistance, while providing pre-arrival instruction of CPR. Firefighters, with EMT training, respond first to deliver immediate Basic Life Support (BLS), pending the arrival of the paramedics. Specially trained paramedics arrive within minutes to provide Advanced Life Support (ALS) and, if needed, can provide transportation to the nearest appropriate Medical Center.[22]

The system is successful due to the blended cooperation between the fire department and paramedic/ambulance services, as well as, a strict policy of meticulous measurement of system performance and cardiac arrest survival information. Strong leadership and regional programs promote uniformity in medical care and response, regardless of jurisdiction.[7]

Another critical element to the Medic One program is the comprehensive training program for the paramedics, one of the most stringent anywhere, making their paramedics some of the most thoroughly trained in the world. Only paramedics with at least three years of prior firefighter or EMT experience may enter the program. Medic One paramedics receive 2,000 hours of instruction, using both “book” studies and hands on field and clinical application through both the University of Washington and Harborview Medical Center. The national standard for paramedic training is just 1,100 hours. Medic One paramedics will have more than 700 patient contacts during their training, which is three times the national standard. Upon completion of training Medic One paramedics are considered to be an extension of the ER doctors and may perform advanced medical care, open airways and administer a variety of medications.[8]

The final component is an emphasis on community based CPR training, called Medic Two. The Seattle/King County area has the highest per capita number of citizens that are trained in the administration of CPR techniques, approximately 50% of its residents.[23]

Leadership

Medic One is operated as a partnership between physicians and administrators. Medical directors review patient care by paramedics and can make recommendations including decertification and termination. Administrators act upon the recommendations of the medical director.[24]

Response

The major components of Medic One's response system are universal access, dispatcher triage, basic life support services, advanced life support services, and transport to hospitals.[21]

A medical 9-1-1 call is handled by one of the following communication centers Seattle Fire Department Alarm Center, Valley Communications Center, North East King County Regional Public Safety Communication Agency, or Port of Seattle Police Department Communications Center.

Medic One dispatchers use criteria based dispatch guidelines to send the most appropriate care providers. The three response levels are basic with advanced life support units, emergency BLS only, and non-emergency BLS only.[25]

The first tier is basic life support provided by cross-trained firefighter emergency medical technician - basics.

The second tier is advanced life support.

Basic life support transports for 9-1-1 calls are provided by either a fire department or one of the private ambulance companies American Medical Response and Tri-Med Ambulance. Advanced life support transports for 9-1-1 calls are provided by paramedics.

Education

All paramedics in King County are graduates of the University of Washington Paramedic Training Program regardless of previous training. The training is 1,866 total hours consisting of 380 lecture hours, 120 lab hours, 466 clinical hours in the operating room and emergency department at Harborview Medical Center and critical care unit and labor and delivery at Seattle Children's Hospital, and 900 field internship hours with Seattle Medic One.[27] Students see an average of 700 patient contacts.

Improvement

The paramedic medical director for the one of six Medic One programs that provided care reviews every resuscitation, intubation, and central-line placement attempt. That director provides both positive and negative feedback. For probationary paramedics a more rigorous review is conducted.[13]

Funding

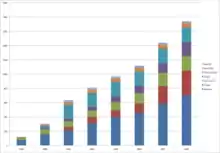

Medic One paramedic programs are funded by a property tax levy. Basic life support services receive partial funding from the levy. The levy passed in 1979, 1985, 1991, 1998, 2001, and 2008.[28] The levy did not pass in 1997.[29]

The Medic One Foundation is a nonprofit charitable foundation supporting paramedic training, research, medical oversight and quality review, and the purchasing of emergency medical equipment.[30]

Performance

Cardiac arrest

A change in the protocol of emergency response personnel is also credited as contributing to the high survival rate in the region. Guidelines set by the American Heart Association in 2000, recommend repeated shocks from a defibrillator and to check for a pulse prior to starting CPR. Medic One guidelines, established in 2005, are to provide a single shock from a defibrillator followed immediately by two minutes of CPR, beginning with chest compressions. This has dropped the average time between first shock to starting CPR from twenty-eight seconds to seven seconds, resulting in a near 50% increase in the previous rate of survival. For every one hundred cardiac arrest calls, now an additional thirteen patients will live.[31]

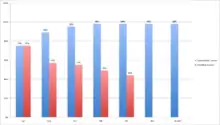

In King County outcomes of attempted out-of-hospital resuscitations are recorded, following the Utstein uniform reporting guidelines, in a cardiac arrest registry. In 2008 Medic One's survival rate for witnessed cardiac arrests due to heart disease prior to EMS arrival with initial rhythm of ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia was 49%.[32]

| 2005[36] | 2006[33] | 2007[34] | 2008[32] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 17% (190/1124) | 18% (174/993) | 18% (191/1035) | 19% (199/1046) |

| Ventricular Fibrillation/Tachycardia (VF/VT) | 30% (132/436) | 40% (125/310) | 40% (120/302) | 47% (151/323) |

| Before EMS Arrival | 16% (164/1015) | 17% (145/875) | 16% (143/899) | 17% (160/920) |

| VF/VT | 29% (113/386) | 36% (100/279) | 36% (97/267) | 39% (112/286) |

| Bystander Witnessed VF/VT Due to Heart Disease | 45% (86/193) | 41% (80/196) | 45% (84/188) | 49% (102/208) |

| Asystole | 1% (6/473) | 1% (5/335) | 2% (6/346) | 2% (8/354) |

| Pulseless Electrical Activity (PEA) | 12% (18/155) | 15% (38/253) | 14% (39/281) | 14% (39/277) |

| Unknown | 100% (1/1) | 25% (2/8) | 33% (1/3) | 25% (1/4) |

| After EMS Arrival | 24% (26/108) | 25% (29/118) | 35% (48/136) | 31% (39/126) |

| VF/VT | 38% (19/50) | 48% (15/31) | 66% (23/35) | 62% (23/37) |

| Asystole | 25% (4/16) | 7% (1/14) | 26% (5/19) | 16% (2/12) |

| PEA | 7% (3/41) | 19% (13/70) | 24% (20/82) | 18% (14/78) |

| Unknown | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/3) | (0/0) | (0/0) |

The average response time for basic life support personnel for cardiac arrests from time of 9-1-1 being dialed to arrival is 4 minutes 40 seconds and for advanced life support personnel is 9 minutes 45 seconds.[37]

In 2008, 58% (530/920) of EMS-treated cardiac arrests not witnessed by EMS in Seattle & King County CPR was initiated by a bystander.[32]

Endotracheal intubation

Seattle Medic One's first-pass success rate for oral endotracheal intubation is 75% (years 2001–2005).[38] Its overall success rate is 98.4%.

Research

- Cardiac Arrest Blood Study (CABS)

- AutoPulse Assisted Prehospital International Resuscitation (ASPIRE) Trial [39]

- Transthoracic Incremental Monophasic Versus Biphasic by Emergency Responders (TIMBER)

- Dispatcher-Assisted Resuscitation Trial (DART)[40]

- Emergency Medical Technician Treatment of Hypoglycemia in the Field

- Induced Hypothermia for Cardiac Arrest Patients

- Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium

- SPHERE Hypertension Intervention Study

- At-Home Automated External Defibrillator (AED) Training Study

Footnotes

- EMS Division 2002, 2002 Strategic Plan Update pg. 53

- EMS Division 2002, 2002 Strategic Plan Update pg. 24

- The local action plan to improve community cardiac arrest survival, section 7

- Seattle Fire Department 2008, pg. 2

- EMS Division 2009, pg. 75

- Cardiac Arrest: The Science and Practice of Resuscitation Medicine, pg. 20

- Davis, Robert (2005-05-20). "Seattle: Firefighters, medics unite to save lives". USA Today. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- "Medic One Facts – Did You Know". Medic One Foundation. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- "King County Medic One". Public Health Seattle & King County. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- "1970 Medic One". University of Washington Department of Research. 1996-09-01. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- Belew, Ellie 2004, pg. 78 - 79 History of Local 2595

- EMS Division 2009, pg. 21

- Eisenberg 2009, pg. 129

- King County Paramedics Association, IAFF Local 2595, The Stations of IAFF 2595

- EMS Division 2009, pg. 15

- "2009 Budget" (PDF). Shoreline Fire Department. 2008-11-20.

- EMS Division 2009, pg. 11

- Bothell's (30,000) + Shoreline's (50,000) populations

- Bellevue's (120,000) + Mercer Island's (20,000) populations

- Duvall's (4,000) + Kirkland's (45,000) + Redmond's (46,000) + Woodinvillie's (9,000) populations

- EMS Division 2009, pg. 9

- "Medic One/Emergency Medical Services – 2008-2013 Strategic Plan". Public Health Seattle & King County. 2007-01-01. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- "In One Hour You Can Become a Gatekeeper". QPR Institute. 1999. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- Eisenberg 2009, pg. 123

- "Criteria Based Dispatch: Improving Emergency Medical Dispatching".

- "Archived copy" (PDF). www.hecb.wa.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Seattle Channel, minute 33:18

- EMS Division 2008, Strategic Plan pg. 11

- EMS Division 2008, Strategic Plan pg. 12

- Medic One Foundation, 2006-07 Financial Highlights

- Black, Cherie (2006-12-12). "SCounty boosts cardiac survival rate - Reason may be a new resuscitation method used by emergency crews". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- EMS Division 2009, pg. 70

- EMS Division 2007, pg. 61

- EMS Division 2008, pg. 64

- Rea TD, Olsufka M, Bemis B, et al. (February 2010). "A population-based investigation of public access defibrillation: role of emergency medical services care". Resuscitation. 81 (2): 163–7. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.10.025. PMID 19962225.

- EMS Division 2006, pg. 55

- Eisenberg 2009, pg. 69

- Warner KJ, Sharar SR, Copass MK, Bulger EM (April 2009). "Prehospital management of the difficult airway: a prospective cohort study". J Emerg Med. 36 (3): 257–65. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.10.058. PMID 18439793.

- Hallstrom A, Rea TD, Sayre MR; et al. (2006). "Manual chest compression vs use of an automated chest compression device during resuscitation following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a randomized trial". JAMA. 295 (22): 2620–2628. doi:10.1001/jama.295.22.2620. PMID 16772625.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Dispatcher-Assisted Resuscitation Trial (DART) - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". Retrieved 2010-02-21.

References

- Eisenberg, Mickey (July 17, 1997). Life in the Balance: Emergency Medicine and the Quest to Reverse Sudden Death. Oxford University Press. pp. 320. ISBN 978-0-19-510179-9.

- Eisenberg, Mickey (April 30, 2009). Resuscitate!: How Your Community Can Improve Survival from Sudden Cardiac Arrest. University of Washington Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-295-98889-4.

- Eisenberg, Mickey (July 2002). "Leonard Cobb and Medic One". Resuscitation. 54 (1): 5–9. doi:10.1016/S0300-9572(02)00146-6. PMID 12104102.

- USA Today: Six Minutes to Live or Die

- Seattle Medic One

- King County Medic One

- Medic One Foundation

- Medic One 40th Anniversary: Seattle Channel

- Public Health - Seattle & King County EMS Division's 2009 EMS Annual Report

- Public Health - Seattle & King County EMS Division's 2008 EMS Annual Report

- Public Health - Seattle & King County EMS Division's 2007 EMS Annual Report

- Public Health - Seattle & King County EMS Division's 2006 EMS Annual Report

- Public Health - Seattle & King County EMS Division's 2005 EMS Annual Report

- Public Health - Seattle & King County EMS Division's 2004 EMS Annual Report

- Public Health - Seattle & King County EMS Division's 2003 EMS Annual Report

- Seattle Fire Department Annual Report 2017

- Medic One/EMS 2014-2019 Strategic Plan - King County

- 2008-2013 Medic One/Emergency Medical Services Strategic Plan

- 2002 Strategic Plan Update of the 1998-2003 Emergency Medical Services Strategic Plan

- South King County Medic One Feasibility Study, 2004