Medical school in the United States

Medical school in the United States is a graduate program with the purpose of educating physicians in the undifferentiated field of medicine. Such schools provide a major part of the medical education in the United States. Most medical schools in the US confer upon graduates a Doctor of Medicine (MD) degree, while some confer a Doctor of Podiatric Medicine (DPM) or Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO) degree. Most schools follow a similar pattern of education, with two years of classroom and laboratory based education, followed by two years of clinical rotations in a teaching hospital where students see patients in a variety of specialties. After completion, graduates must complete a residency before becoming licensed to practice medicine.

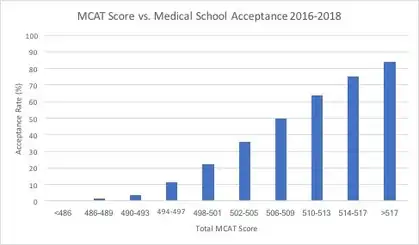

Admissions to medical school in the United States is generally considered highly competitive, although there is a wide range of competitiveness among different types of schools. In 2021, approximately 36% of those who applied to MD-Granting US medical schools gained admission to any school.[1] Admissions criteria include grade point averages, Medical College Admission Test scores, letters of recommendation, and interviews. Most students have at least a bachelor's degree, usually in a biological science, and some students have advanced degrees, such as a master's degree. Medical school in the United States does not require a degree in biological sciences, but rather a set of undergraduate courses in scientific disciplines thought to adequately prepare students.

The Flexner Report, published in 1910, had a significant impact on reforming medical education in the United States. The report led to the implementation of more structured standards and regulations in medical education. Currently, all medical schools in the United States must be accredited by a certain body, depending on whether it is a D.O. granting medical school or an M.D. granting medical school. The Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) is an accrediting body for educational programs at schools of medicine in the United States and Canada. The LCME accredits only the schools that grant an M.D. degree; osteopathic medical schools that grant the D.O. degree are accredited by the Commission on Osteopathic College Accreditation of the American Osteopathic Association. The LCME is sponsored by the Association of American Medical Colleges and the American Medical Association.

History

_(14779331564).jpg.webp)

Many of the early medical schools in the United States were founded by alumni of the University of Edinburgh Medical School, the oldest medical school in the United Kingdom and one of the oldest medical schools in the English-speaking world. A majority of these schools were established within Northeast colleges that today make up the Ivy League, and modeled after their founders' coursework at Edinburgh. The nation's first medical school opened in 1765 at the College of Philadelphia by John Morgan and William Shippen Jr.; this school developed over time into the University of Pennsylvania's Perelman School of Medicine.[3] In 1767, Dr. Samuel Bard, an alumnus of then-King's College, opened a short-lived medical school that ultimately was forced to close in 1776 at the onset of the American Revolution. The school reopened in 1784 and, after a period of struggle, merged with the New York College of Physicians and Surgeons to become Columbia University's Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1814. By the turn of the 19th century, four medical schools had been established in the United States, with Harvard Medical School opening in 1782,[4] followed by Dartmouth Medical School in 1797.[5] Dartmouth, founded by Nathan Smith, was the first medical school established outside of a major US city, and the first medical school founded in the independent United States after the end of the revolutionary war. Smith went on to also establish three other New England medical schools: the Medical Institution of Yale College (1810), the now-defunct Medical School of Maine (1821), and the University of Vermont College of Medicine (1822). The first public medical school in the United States, the University of Maryland School of Medicine, was founded in 1807 as the College of Medicine of Maryland and became the founding school of the University System of Maryland.

As medical colleges began to proliferate across the young nation in the 19th century, the American Medical Association was formed in 1847. Almost thirty years later in 1876, the Association of American Medical Colleges was established to develop a set of standards for the education provided at US medical schools.[6]

In 1910, the Flexner Report reported on the state of medical education in the United States and Canada. Written by Abraham Flexner and published in 1910 under the aegis of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, the report set standards and reformed American medical education. This report led to the demise of many non-university based medical schools.[7]

After World War I, the standard practice of completing an internship after medical school became a commonplace requirement to practice medicine,[8] and a list of approved hospitals for the training of interns was complied. In 1928, the AMA published a set of guidelines for residencies.[9]

In 1940, the Report of the Commission on Graduate Medical Education was published, which first described the overworking of interns and residents.[8] The Liaison Committee on Medical Education was established in 1942.[10]

Combination programs granting a bachelor's degree and medical degree are relatively rare in the US. Baccalaureate-MD programs opened for the first time in 1961 at Northwestern University Medical School and Boston University School of Medicine. By the 1990s, 34 programs had opened, and in 2011, these programs were offered at 57 medical schools. Several of these schools offer programs in combination with more than one undergraduate institution, for a total of 81 programs.[11] In all current combination programs admitting graduating high school students to receive both a bachelors and a medical degree, the medical education portion is four years in length. 80% of the programs are 8 years in length, giving no time advantage to students over the standard process, but 21% offer a compressed 6- or 7-year program. This is different from the programs of the 1990s, where 42% of programs were 8 years, 32% were 7 years, and 23% were 6 years.[11]

For years following the Flexner report,[12] medical education in the United States has followed a standardized pattern, with two years of classroom education, followed by two years of clinical experience. Since the early 2010s, the idea of shortening medical school to three years once again has been raised as a solution to the massive debt facing medical graduates and the growing shortage of physicians in primary care specialties.[13][14] A small number of universities are experimenting with three-year programs. New York University offers a 3-year program with an early acceptance into a residency program for students that wish to apply for a specific specialty before beginning their medical education.[15] A handful of universities, including the Penn State College of Medicine, University of California Davis School of Medicine, and Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, offer these programs for students that commit to entering a family medicine residency.[16]

Admissions

In general, admission into a US medical school is considered highly competitive and typically requires completion of a four-year Bachelor's degree or at least 90 credit hours from an accredited college or university. Many applicants obtain further education before medical school in the form of Master's degrees or other non science-related degrees. Admissions criteria may include overall performance in the undergraduate years and performance in a group of courses specifically required by U.S. medical schools (pre-health sciences), the score on the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT), application essays, letters of recommendation (most schools require either one letter from the undergraduate institution's premedical advising committee or a combination of letters from at least one science faculty and one non-science faculty), and interviews.[17]

Beyond objective admissions criteria, many programs look for candidates who have had unique experiences in community service, volunteer work, international studies, research, or other advanced degrees. The application essay is the primary opportunity for the candidate to describe their reasons for entering a medical career. The essay requirements are usually open-ended to allow creativity and flexibility for the candidate to draw upon their personal experiences/challenges to make him/her stand out amongst other applicants. If granted, an interview serves as an additional way to express these subjective strengths that a candidate may possess.[18]

Since 2005, the Association of American Medical Colleges has recommended that all medical schools conduct background checks on applicants in order to prevent individuals with convictions for serious crimes from being matriculated.[19]

Most commonly, the bachelor's degree is in one of the biological sciences, but not always; in 2020, nearly 40% of medical school matriculates had received bachelor's degrees in fields other than biology or specialized health sciences.[20] All medical school applicants must, however, complete undergraduate courses with labs in biology, general chemistry, organic chemistry, and physics; some medical schools have additional requirements such as biochemistry, calculus, genetics, psychology and English. Many of these courses have prerequisites, so there are other "hidden" course requirements (basic science courses) that are often taken first. Concerns have been raised that these stringent science requirements constrict the applicant pool and deter many potentially talented future physicians, including those from groups historically underrepresented in medicine, from applying.[21]

A student with a bachelor's degree who has not taken the pre-medical coursework may complete a post-baccalaureate (postbacc) program. Such programs allow rapid fulfillment of prerequisite course work as well as grade point average improvement. Some postbacc programs are specifically linked to individual medical schools to allow matriculation without a gap year, while most require 1–2 years to complete.[22] Post-bacc programs have become popular among applicants to medical school. The New York Times reported, that in 2011, more than 15 percent of the new medical students had gone through one of such a programs.[22] Studies have shown that graduates of post-baccalaureate programs were more likely to be providing care in federally designated underserved areas and/or providing care to vulnerable populations. [23][24]

Several universities[25] across the U.S. admit college students to their medical schools during college; students attend a single six-year to eight-year integrated program consisting of two to four years of an undergraduate curriculum and four years of medical school curriculum, culminating in both a bachelor's and M.D. degree or a bachelor's and D.O. degree. Some of these programs admit high school students to college and medical school.

While not necessary for admission, several private organizations have capitalized on this complex and involved process by offering services ranging from single-component preparation (MCAT, essay, etc.) to entire application review/consultation.

In 2020, the average MCAT and GPA for students entering U.S.-based M.D. programs were 511.5 (approximately 82nd percentile) and 3.73[27] respectively, and (as of 2018) 504 and 3.54 for D.O. matriculants.[28]

In 2020–2021, 53,030 people applied to MD-Granting medical schools in the United States through the American Medical College Application Service. Of these 45,266 students, 22,239 of them matriculated into a medical school for a success rate of 42 percent.[27] However, this figure does not account for the attrition rate of pre-med students in various stages of the pre-application process (those who ultimately do not decide to apply due to weeding out by low GPA, low MCAT, lack of clinical and research experience, and numerous other factors).[29]

Curriculum

Medical school typically consists of four years of education and training, although a few programs offer three-year tracks. Traditionally, the first two years consist of basic science and clinical medicine courses, such as anatomy, biochemistry, histology, microbiology, pharmacology, physiology, cardiology, pulmonology, gastroenterology, endocrinology, psychiatry, and neurology. DO students also study Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine. USMLE Step 1/COMLEX Level 1 of the medical licensing boards are taken at the completion of the preclinical phase of study.

Traditionally medical schools have divided the first year into the basic science courses and the second year into clinical science courses, but it has been increasingly common since the mid-2000s for schools to follow a "systems-based" curriculum, where students take shorter courses that focus on one organ or functional system at a time, and relevant topics such as pharmacology are integrated.[30] [31]

The third and fourth years consist of clinical rotations, sometimes called clerkships, where students see patients in hospitals and clinics. These rotations are usually at teaching hospitals but are occasionally at community hospitals or with private physicians. Mandatory rotations in third year are often obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, psychiatry, family medicine, internal medicine, and surgery. During the third year, medical students take Step 2/Level 2 of the medical licensing boards. Fourth year rotations typically allow students to choose several electives and finish required rotations. It is also used as a period of auditioning for residency programs.

Dual degree programs

Many medical schools also offer joint degree programs in which some medical students may simultaneously enroll in master's or doctoral-level programs in related fields such as a Masters in Business Administration, Masters in Healthcare Administration, Masters in Public Health, JD, Master of Arts in Law and Diplomacy, and Masters in Health Communication. Some schools, such as the Wayne State University School of Medicine and the Medical College of South Carolina, both offer an integrated basic radiology curriculum during their respective MD programs led by investigators of the Advanced Diagnostic Ultrasound in Microgravity study.

Upon completion of medical school, the student gains the title of doctor and the degree of M.D. or D.O. but cannot practice independently until completing at least an internship and also Step 3 of the USMLE (for M.D.) or COMLEX (for D.O.). Doctors of Medicine and Doctors of Osteopathic Medicine have an equal scope of practice in the United States, with some osteopathic physicians supplementing their practice with principles of osteopathic medicine.[32][33]

Grading

Medical schools use a variety of different grading methods. Even within one school, the grading of the basic sciences and clinical clerkships may vary. Most medical schools use the pass/fail schema, rather than letter grades; however the range of grading intervals varies. In addition, sometimes it is important to evaluate the overall sense of how collaborative a student body is instead of basing judgment solely on grading intervals (i.e. a school with honors can still be very collaborative while some schools with pass/fail grading can be very competitive and individualistic). The following are examples of grades used with different intervals:[34]

- 2 Intervals = Pass/Fail

- 3 Intervals = Honors/Pass/Fail

- 4 Intervals = Honors/High Pass/Pass/Fail (or ABCF)

- 5 Intervals = Honors/High Pass/Pass/Low Pass/Fail (or ABCDF)

At some schools, a Medical Student Performance Evaluation, also called Dean's letter, more specifically describes the performance of a student during medical school.[35][36]

Research

Social and personal effects of medical school

With the many demands being placed on medical students, maintaining a healthy lifestyle can often be difficult.

Physician suicide has risen in the public's awareness recently, and studies show that even as medical students, trainees have depression rates that are over 15% higher than the general population.[37] In recent years, reports of suicide in unmatched residency applicants has drawn attention to medical student and physician suicide.[38] For those who have developed good exercise habits, continuing to do so may not be difficult. However, for students who have not yet developed the habit, they may find their physical well-being exacerbated by their new stressful lifestyle.[39][40] Maintaining long-term relationships is also often a challenge.[41][42][43]

Accreditation

All medical schools within the United States must be accredited by one of two organizations. The Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), jointly administered by the Association of American Medical Colleges and the American Medical Association, accredits M.D. schools,[44] while the Commission on Osteopathic College Accreditation of the American Osteopathic Association accredits osteopathic (D.O.) medical schools. There are presently 154 M.D. programs[45] and 38 D.O. programs[46] in the United States.

Accreditation is required for a school's students to receive federal loans. Additionally, schools must be accredited to receive federal funding for medical education.[47] The M.D. and D.O. are the only medical degrees offered in the United States which are listed in the WHO/IMED list of medical schools.

Finances

The normal cost to attend medical school can range from over $100,000 a year. However, with average debt of graduates rising, it is important to medical students to be aware of their financial situation when starting out in and during medical school, as well as when planning for their future.[48][49]

The median four-year cost of medical school (including expenses and books) was $278,455 for private schools, and $207,866 for public schools in 2013 according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.[50] This doesn't include the opportunity cost ("lost opportunity") of attending school.

Exceptions

- Exceptions to free with over $20,000/yr stipend (MSTP, Military scholarship). Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences has an age requirement of "no older than 36 as of June 30 in the year of matriculation."[51]

- In 2018, New York University Medical School announced that all current and new students would receive full-tuition scholarship.[52]

- In 2019, Washington University Medical School announced that more than half of students would receive full-tuition scholarships.[53]

Indebtedness of medical graduates

The rising cost of medical education has caused concern. In 1986, the mean debt accumulated in medical school was $32,000, which is approximately $70,000 in 2017 dollars. In 2016, the mean medical school debt was $190,000. However, in 2016, 27% of medical students graduated with no debt. This is a large increase from 2010, when 16% of students had no debt upon graduation. According to the Journal of the American Medical Association, scholarship funds among those graduating without debt dropped by more than half, from $135,186 in 2010 to $52,718 in 2016.[54] This suggests that the increase in students graduating without debt is due to personal wealth rather than decreased cost of attending medical school. Additionally, with an increase in total debt and a decrease in the number of students carrying debt, the debt accumulated by medical students is increasingly being concentrated in fewer students with larger debt loads.[54]

A current economic theory suggests that increasing borrowing limits may have been the cause of the increased tuition. As medical students are allowed to borrow more, medical schools raise tuition prices to maximally increase revenue. A study by the Cato Institute shows that schools raise prices 97 cents for each one dollar increase in borrowing capacity.[55]

There is no consensus on whether the level of debt carried by medical students has a strong effect on their choice of medical specialty. Dr. Herbert Pardes and others have suggested that medical school debt has been a direct cause of the US primary care shortage.[56] However, the amount of debt carried by medical graduates suggests the opposite. Students in more competitive specialties had significantly less debt on graduation, meaning that they weren't reliant on higher future compensation to repay loans. In 2016, 80% of family medicine residents graduated with debt, while only 74% of anesthesiology residents and 60% of ophthalmology residents graduated with any debt. The mean debt of students that did have debt entering family medicine residencies was $181,000, while the mean debt of those entering dermatology residencies was $153,000.[54]

In February 2010, The Wall Street Journal published a story of Dr Michelle Bisutti's $555,000 medical school debt. The huge amount of debt is a direct result of Bisutti deferring her student debt payment during her residency.[57]

Indebtedness Relief Programs

Income-based repayment (IBR) and Pay as You Earn (PAYE) give options to lower monthly repayment based on adjusted gross income (AGI) for all Federal student loans. Physicians in public service are also eligible for student loan forgiveness after ten years of loan payment while in a public service job.[58]

Repayment options that lower monthly payments and student loan forgiveness (PSLF) in public service are advised to medical residents slated to earn much higher salaries after residency.[59] Among 2019 graduates, 34% reported planning to pursue PSLF and 56% reported no plans to enter a loan forgiveness program.[60]

Academic health centers

Most MD schools are programs within multi-purpose institutions known as academic health centers. Academic health centers aim to educate medical students and residents, provide top-quality patient care, and perform research to advance the field of medicine. Since medical students are educated inside academic health centers, it is impossible to separate the finances from other operations inside the center. Funding for medical students—and higher graduate medical education—comes from several sources above and beyond personal debt financing.[61]

- DGME (Direct Graduate Medical Education- 2.2 billion in 2002) financing payments under the auspices of Medicare/Medicaid. This funding was altered by the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1986. Each hospital receives payment based on how many Full Time Equivalent Residents are being trained.

- IME (Indirect Medical Education - 6.2 billion in 2002) adjustment. This payment compensates teaching hospitals for their higher Medicare inpatient hospital operating costs due to a number of factors.

- Managed care and insurance organizations reimburse at a higher rate for teaching hospitals, explicitly acknowledging the higher costs of the academic health center.

- The vast majority of revenues come from third-party payers reimbursing for patient care, usually through the Faculty Service Plan.

- Incentive programs such as the MSTP (Medical Scientist Training Program), NHSC (National Health Service Corps), Armed Services Health Profession Scholarship and now the Income Based Repayment Plan.

- Many academic health centers in the U.S. are tied to undergraduate university systems while others solely focus on graduate medicine, training, research, and education.

References

- "AAMC Facts". www.aamc.org. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- Blough, Barbara T.; Grossman, Dana Cook (1999). "Two Hundred Years of Medicine at Dartmouth". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 882 (1): xiii–xix. Bibcode:1999NYASA.882D..13B. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08526.x. ISSN 1749-6632. S2CID 84139859.

- Fee, Elizabeth (2015). "The first American medical school: The formative years". The Lancet. 385 (9981): 1940–1. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60950-3. PMID 26090632. S2CID 19516181.

- "Search - HMS". Hms.harvard.edu. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Dartmouth Medical School Founded: 1797". 16 October 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- "About Us". Acgme.org. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- Dezee, Kent J; Artino, Anthony R; Elnicki, D. Michael; Hemmer, Paul A; Durning, Steven J (2012). "Medical education in the United States of America". Medical Teacher. 34 (7): 521–5. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.668248. PMID 22489971. S2CID 30137802.

- Ludmerer, Kenneth M; Johns, Michael M. E (2005). "Reforming Graduate Medical Education". JAMA. 294 (9): 1083–7. doi:10.1001/jama.294.9.1083. PMID 16145029.

- "History of Medical Education". Acgme.org. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Looking Back and Moving Forward—75 Years of the LCME". news.aamc.org. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- Eaglen, Robert H; Arnold, Louise; Girotti, Jorge A; Cosgrove, Ellen M; Green, Marianne M; Kollisch, Donald O; McBeth, Dani L; Penn, Mark A; Tracy, Sarah W (2012). "The Scope and Variety of Combined Baccalaureate–MD Programs in the United States". Academic Medicine. 87 (11): 1600–8. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826b8498. PMID 23018320.

- Irby, David M; Cooke, Molly; Oʼbrien, Bridget C (2010). "Calls for Reform of Medical Education by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching: 1910 and 2010". Academic Medicine. 85 (2): 220–7. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c88449. PMID 20107346.

- Goldfarb, Stanley; Morrison, Gail (2013). "The 3-Year Medical School—Change or Shortchange?". New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (12): 1087–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1306457. PMID 24047056.

- Boodman, Sandra G. (13 January 2014). "Medical school done faster". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Accelerated Three-Year MD at NYU School of Medicine". NYU Langone Health. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Consortium of Accelerated Medical Pathway Programs". NYU Langone Health. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Admission Requirements". AAMC. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- "Anatomy of An Applicant". Association of American Medical Colleges. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- Appel, Jacob M. "Should Convicted Murderers Practice Medicine?" Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, Vol. 19, No. 4, Oct. 2010

- "Table A‐17: MCAT and GPAs for Applicants and Matriculants to U.S. Medical Schools by Primary Undergraduate Major, 2020‐2021". Association of American Medical Colleges. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- Appel Jacob M. Medical School: The Wrong Applicant Pool. The Hastings Center Report 49(2):6-8 · March 2019

- Cecilia Capuzzi Simon (April 13, 2012). "A Second Opinion: The Post-Baccalaureate". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- Andriole, Dorothy A. MD; Jeffe, Donna B. PhD (February 2011). "Characteristics of Medical School Matriculants Who Participated in Postbaccalaureate Premedical Programs". Academic Medicine. 86 (2): 201–210. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182045076. PMC 3213404. PMID 21169786.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Smitherman, Herbert C. MD, MPH; Aranha, Anil N.F. PhD; Matthews, De'Andrea DRE; Dignan, Andrew; Morrison, Mitchell MPH; Ayers, Eric MD; Robinson, Leah PhD; Smitherman, Lynn C. MD; Sprague, Kevin J. MD; Baker, Richard S. MD (March 2021). "Impact of a 50-Year Premedical Postbaccalaureate Program in Graduating Physicians for Practice in Primary Care and Underserved Areas". Academic Medicine. 96 (3): 416–424. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003846. PMID 33177321. S2CID 226311644. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - AAMC: Schools Offering Combined Degree Programs in BS/MD Archived 2005-10-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "MCAT and GPA Grid for Applicants and Acceptees to U.S. Medical Schools, 2016-2017 through 2017-2018" (PDF).

- "Table A‐18: MCAT Scores and GPAs for Applicants and Matriculants to U.S. Medical Schools by Race/Ethnicity, 2020‐2021". 27 October 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- "AACOM Reports on Matriculants" (PDF). AACOM. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- Rao, S; van Holsbeeck, L; Musial, JL; Parker, A; Bouffard, JA; Bridge, P; Jackson, M; Dulchavsky, SA (May 2008). "A pilot study of comprehensive ultrasound education at the Wayne State University School of Medicine: a pioneer year review". Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 27 (5): 745–9. doi:10.7863/jum.2008.27.5.745. PMID 18424650. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- Lovenheim, Sarah (10 November 2009). "Medical schools revise curricula to adapt to changing world". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "POLICY PRIORITIES TO IMPROVE OUR NATION'S HEALTH : HOW MEDICAL EDUCATION IS CHANGING" (PDF). Aamc.org. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Dual Degree Programs - Stanford Medicine". Med.stanford.edu. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Consider a Joint M.D. Degree | Medical School Admissions Doctor | US News". Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2017-09-04.

- AAMC: Grading Intervals Archived 2009-09-06 at the Wayback Machine

- McGill Archived 2008-02-20 at the Wayback Machine - Medical School Performance Evaluation (Dean's Letter)

- "Medical Student Performance Evaluation (MSPE)".

- "Healthcare Professional Burnout, Depression and Suicide Prevention". Afsp.org. 21 November 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "The Mental Health Toll of not matching". .medpagetoday.com. 7 July 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- "Staying Sane: Addressing the Growing Concern of Mental Health in Medical Students - AMSA". Amsa.org. 8 September 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- Dacey, Marie L; Kennedy, Mary A; Polak, Rani; Phillips, Edward M (2014). "Physical activity counseling in medical school education: A systematic review". Medical Education Online. 19: 24325. doi:10.3402/meo.v19.24325. PMC 4111877. PMID 25062944.

- "USMLE Tips, Study Plans, and Practice - Kaplan Test Prep". Kaptest.com. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Evaluate Priorities to Balance Personal Life, Medical School | Medical School Admissions Doctor | US News". Archived from the original on 2017-09-07. Retrieved 2017-09-04.

- "5 Keys to Maintaining a Healthy Relationship in Med School - The Almost Doctor's Channel". Almost.thedoctorschannel.com. 14 April 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- Wiebe, Christina. The LCME at a Glance Archived 2007-10-19 at the Wayback Machine. The New Physician, American Medical Student Association. December 1999. accessed 4 Nov 2007.

- "Medical Schools". Association of American Medical Colleges. Archived from the original on 12 August 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- "1 in 4 U.S. medical students attends an osteopathic medical school". AACOM. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- LCME: Frequently Asked Questions Archived 2012-08-03 at archive.today

- "What's the Real Cost of Medical School? - Kaplan Test Prep". Kaptest.com. 26 February 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Medical School Scholarships". Medicineandthemilitaray/com. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Is Medical School Worth it Financially?".

- "Admission Requirements | Uniformed Services University". www.usuhs.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-01-08.

- "Cost of Attendance". NYU Langone Health. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- "Washington University commits $100 million to MD scholarships, education". Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. 2019-04-16. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- Grischkan, Justin; George, Benjamin P; Chaiyachati, Krisda; Friedman, Ari B; Dorsey, E. Ray; Asch, David A (2017). "Distribution of Medical Education Debt by Specialty, 2010-2016". JAMA Internal Medicine. 177 (10): 1532–1535. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4023. PMC 5820693. PMID 28873133.

- "Making College More Expensive: The Unintended Consequences of Federal Tuition Aid". Cato.org. 25 January 2005. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- Pardes, Herbert (6 November 2009). "The Coming Shortage of Doctors". The Wall Street Journal.

- Pilon, Mary (2010-02-13). "Error Page - Wsj.com". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Student Loan Repayment - Medical Schools and Students - Government Affairs - AAMC". Aamc.org. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Repaying high student debt". Archived from the original on 3 March 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Physician Education Debt and the Cost to Attend Medical School". AAMC. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- Knapp, R. M (2002). "Complexity and uncertainty in financing graduate medical education". Academic Medicine. 77 (11): 1076–83. doi:10.1097/00001888-200211000-00003. PMID 12431915.

External links

Medical school associations

Application services

- American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine Application Service (D.O. schools)

- Association of American Medical Colleges Online Application (M.D. schools)

- Texas Medical & Dental Schools Application Service (All public Texas M.D. and D.O. schools)