Neuroscientist

A neuroscientist (or neurobiologist) is a scientist who has specialised knowledge in neuroscience, a branch of biology[1] that deals with the physiology, biochemistry, psychology, anatomy and molecular biology of neurons, neural circuits, and glial cells and especially their behavioral, biological, and psychological aspect in health and disease. [2]

Neuroscientists generally work as researchers within a college, university, government agency, or private industry setting.[3] In research-oriented careers, neuroscientists typically spend their time designing and carrying out scientific experiments that contribute to the understanding of the nervous system and its function. They can engage in basic or applied research. Basic research seeks to add information to our current understanding of the nervous system, whereas applied research seeks to address a specific problem, such as developing a treatment for a neurological disorder. Biomedically-oriented neuroscientists typically engage in applied research. Neuroscientists also have a number of career opportunities outside the realm of research, including careers in industry, science writing, government program management, science advocacy, and education.[4] These individuals most commonly hold doctorate degrees in the sciences, but may also hold a master's degree.

Job overview

Job description

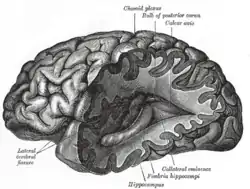

Neuroscientists focus primarily on the study and research of the nervous system. The nervous system is composed of the brain, spinal cord and nerve cells. Studies of the nervous system may focus on the cellular level, as in studies of the ion channels, or instead may focus on a systemic level as in behavioural or cognitive studies. A significant portion of nervous system studies is devoted to understanding the diseases that affect the nervous system, like multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Lou Gehrig's. Research commonly occurs in private, government and public research institutions and universities.[5]

Some common tasks for neuroscientists are:[6]

- Developing experiments and leading groups of people in supporting roles

- Conducting theoretical and computational neuronal data analysis

- Research and development of new treatments for neurological disorders

- Working with doctors to perform experimental studies of new drugs on willing patients

- Following safety and sanitation procedures and guidelines

- Dissecting experimental specimens

Salary

The overall median salary for neuroscientists in the United States was $79,940 in May 2014. Neuroscientists are usually full-time employees. Median salaries at common work places in the United States are shown below.[6]

| Common Work Places | Median Annual Pay |

|---|---|

| Colleges and universities | $58,140 |

| Hospitals | $73,590 |

| Laboratories | $82,700 |

| Research and Development | $90,200 |

| Pharmaceutical | $150,000 |

Work environment

Neuroscientists research and study both the biological and psychological aspects of the nervous system.[6] Once neuroscientists finish their post doctoral programs, 39% go on to perform more doctoral work, while 36% take on faculty jobs.[7] Neuroscientists use a wide range of mathematical methods, computer programs, biochemical approaches and imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography angiography, and diffusion tensor imaging.[8] Imaging techniques allow scientists to observe physical changes in the brain and spinal cord, as signals occur. Neuroscientists can also be part of several different neuroscience organizations where they can publish and read different research topics.

Job outlook

Neuroscience is expecting job growth of about 8% from 2014 to 2024, a considerably average job growth rate when compared to other professions. Factors leading to this growth include an aging population, new discoveries leading to new areas of research, and increasing utilization of medications. Government funding for research will also continue to influence the demand for this specialty.[6]

Education

Neuroscientists typically enroll in a four-year undergraduate program and then move on to a PhD program for graduate studies. Once finished with their graduate studies, neuroscientists may continue doing postdoctoral work to gain more lab experience and explore new laboratory methods. In their undergraduate years, neuroscientists typically take physical and life science courses to gain a foundation in the field of research. Typical undergraduate majors include biology, behavioral neuroscience, and cognitive neuroscience.[9]

Many colleges and universities now have PhD training programs in the neurosciences, often with divisions between cognitive, cellular and molecular, computational and systems neuroscience.

Interdisciplinary fields

Neuroscience has a unique perspective in that it can be applied in a broad range of disciplines, and thus the fields neuroscientists work in vary. Neuroscientists may study topics from the large hemispheres of the brain to neurotransmitters and synapses occurring in neurons at a micro-level. Some fields that combine psychology and neurobiology include cognitive neuroscience, and behavioural neuroscience. Cognitive neuroscientists study human consciousness, specifically the brain, and how it can be seen through a lens of biochemical and biophysical processes.[10] Behavioral neuroscience encompasses the whole nervous system, environment and the brain how these areas show us aspects of motivation, learning, and motor skills along with many others.[11] Computational neuroscience uses mathematical models to understand how the brain processes information.[12]

History

Egyptian understanding and early Greek philosophers

Some of the first writings about the brain come from the Egyptians. In about 3000 BC the first known written description of the brain also indicated that the location of brain injuries may be related to specific symptoms. This document contrasted common theory at the time. Most of the Egyptians' other writings are very spiritual, describing thought and feelings as responsibilities of the heart. This idea was widely accepted and can be found into 17th century Europe.[13]

Plato believed that the brain was the locus of mental processes. However, Aristotle believed instead the heart to be the source of mental processes and that the brain acted as a cooling system for the cardiovascular system.[14]

Galen

In the Middle Ages, Galen made a considerable impact on human anatomy. In terms of neuroscience, Galen described the seven cranial nerves' functions along with giving a foundational understanding of the spinal cord. When it came to the brain, he believed that sensory sensation was caused in the middle of the brain, while the motor sensations were produced in the anterior portion of the brain. Galen imparted some ideas on mental health disorders and what caused these disorders to arise. He believed that the cause was backed-up black bile, and that epilepsy was caused by phlegm. Galen's observations on neuroscience were not challenged for many years.[15]

Medieval European beliefs and Andreas Vesalius

Medieval beliefs generally held true the proposals of Galen, including the attribution of mental processes to specific ventricles in the brain. Functions of regions of the brain were defined based on their texture and composition: memory function was attributed to the posterior ventricle, a harder region of the brain and thus a good place for memory storage.[13]

Andreas Vesalius redirected the study of neuroscience away from the anatomical focus; he considered the attribution of functions based on location to be crude. Pushing away from the superficial proposals made by Galen and medieval beliefs, Vesalius did not believe that studying anatomy would lead to any significant advances in the understanding of thinking and the brain.[13]

Current and developing research topics

Research in neuroscience is expanding and becoming increasingly interdisciplinary. Many current research projects involve the integration of computer programs in mapping the human nervous system. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) sponsored Human Connectome Project, launched in 2009, hopes to establish a highly detailed map of the human nervous system and its millions of connections. Detailed neural mapping could lead the way for advances in the diagnosis and treatment of neurological disorders.

Neuroscientists are also at work studying epigenetics, the study of how certain factors that we face in our everyday lives not only affect us and our genes but also how they will affect our children and change their genes to adapt to the environments we faced.

Behavioral and developmental studies

Neuroscientists have been working to show how the brain is far more elastic and able to change than we once thought. They have been using work that psychologists previously reported to show how the observations work, and give a model for it.

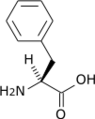

One recent behavioral study is that of phenylketonuria (PKU), a disorder that heavily damages the brain due to toxic levels of the amino acid phenylalanine. Before neuroscientists had studied this disorder, psychologists did not have a mechanistic understanding as to how this disorder caused high levels of the amino acid and thus treatment was not well understood, and oftentimes, was inadequate. The neuroscientists that studied this disorder used the previous observations of psychologists to propose a mechanistic model that gave a better understanding of the disorder at the molecular level. This in turn led to better understanding of the disorder as a whole and greatly changed treatment that led to better lives for patients with the disorder.[16]

Another recent study was that of mirror neurons, neurons that fire when mimicking or observing another animal or person that is making some sort of expression, movement, or gesture. This study was again one where neuroscientists used the observations of psychologists to create a model for how the observation worked. The initial observation was that newborn infants mimicked facial expressions that were expressed to them. Scientists were not certain that newborn infants were developed enough to have complex neurons that allowed them to mimic different people and there was something else that allowed them to mimic expressions. Neuroscientists then provided a model for what was occurring and concluded that infants did in fact have these neurons that fired when watching and mimicking facial expressions.[16]

Effects of early experience on the brain

Neuroscientists have also studied the effects of "nurture" on the developing brain. Saul Schanberg and other neuroscientists did a study on how important nurturing touch is to the developing brains in rats. They found that the rats who were deprived of nurture from the mother for just one hour had reduced functions in processes like DNA synthesis and hormone secretion.[16]

Michael Meaney and his colleagues found that the offspring of mother rats who provided significant nurture and attention tended to show less fear, responded more positively to stress, and functioned at higher levels and for longer times when fully mature. They also found that the rats who were given much attention as adolescents also gave their offspring the same amount of attention and thus showed that rats raised their offspring similar to how they were raised. These studies were also seen on a microscopic level where different genes were expressed for the rats that were given high amounts of nurture and those same genes were not expressed in the rats who received less attention.[16]

The effects of nurture and touch were not only studied in rats, but also in newborn humans. Many neuroscientists have performed studies where the importance of touch is shown in newborn humans. The same results that were shown in rats, also held true for humans. Babies that received less touch and nurture developed slower than babies that received a lot of attention and nurture. Stress levels were also lower in babies that were nurtured regularly and cognitive development was also higher due to increased touch.[16] Human offspring, much like rat offspring, thrive off of nurture, as shown by the various studies of neuroscientists.

Famous neuroscientists

Neuroscientists awarded Nobel Prizes in physiology or medicine

- Thomas C. Südhof (2013) for the discovery of the precise neurotransmitters release control system.[17]

May-Britt Moser, co-winner of 2014 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

May-Britt Moser, co-winner of 2014 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

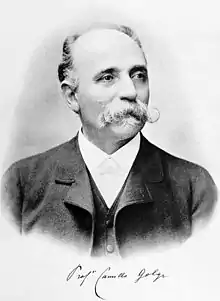

- Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1906) for the development of the silver staining method, revealing what would later be determined as individual neurons. Cajal's interpretations of the images produced by Golgi's staining technique led to the adoption of the neuron doctrine.[18]

- Charles Sherrington and Edgar Adrian (1932) for their discoveries of the general function of neurons, including excitatory and inhibitory signals, and the all-or-nothing response of nerve fibers.[19]

- Sir Henry Dale and Otto Loewi (1936) for the discovery of neurotransmitters and identification of acetylcholine.[20]

- Joseph Erlanger and Herbert Gasser (1944) for discoveries illustrating the varied timing exhibited by single nerve fibers.[21]

- Walter Rudolf Hess and António Caetano Egas Moniz (1949) for discovery of the functional organization of the midbrain and for the controversial[22] therapeutic value of leucotomy respectively.

- Alan Hodgkin, Andrew Huxley, and Sir John Eccles (1963) for discovering the ionic basis of the action potential and macroscopic currents through their use of the squid giant axon.[23]

- Sir Bernard Katz, Ulf von Euler and Julius Axelrod (1970) for the discovery of the mechanisms responsible for neurotransmitter storage, release, and inactivation. Their work included the discovery of the synaptic vesicle and quantal neurotransmitter release.[24]

- Roger Guillemin and Andrew V. Schally (1977) for discovering the production on the brain of the peptide hormone.[25]

- Roger W. Sperry, David H. Hubel and Torsten N. Wiesel (1981) for discoveries concerning the cerebral hemispheres specialization and the visual system respectively.[26]

- Stanley Cohen and Rita Levi-Montalcini (1986) for their discovery of nerve growth factor (NGF) as well as epidermal growth factor (EGF).[27]

- Erwin Neher and Bert Sakmann (1991) for the development of the patch-clamp recording technique, allowing, for the first time, the observation of current flow through individual ion channels. Neher and Sakmann additionally characterized the specificity of ion channels.[28]

- Arvid Carlsson, Paul Greengard and Eric Kandel (2000) for the discovery of neural signal transduction pathways upon neurotransmitter binding, as well as the establishment of dopamine as a primary acting neurotransmitter.[29]

- Richard Axel and Linda B. Buck (2004) for their discoveries concerning the olfactory system[30]

- John O'Keefe, Edvard I. Moser and May-Britt Moser (2014) for their discoveries of cells that constitute a positioning system in the brain.[31]

- Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael Rosbash and Michael W, Young (2017) "for their discoveries of molecular mechanisms controlling the circadian rhythm"[32]

Neuroscientists in popular culture

- Victor Frankenstein, title character of Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus

- Amy Farrah Fowler, Ph.D, main character in CBS's The Big Bang Theory. She is played by Mayim Bialik, who also holds a Ph.D. in neuroscience.

- Dr. Cameron Goodkin, main character in Stitchers. Before his work at the NSA, he was a researcher at MIT.

See also

- List of neuroscientists

- List of women neuroscientists

- International Brain Research Organization

- Society for Neuroscience

References

- "the definition of neurobiology". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- "Definition of Neuroscience".

- "Neuroscience Jobs Available in a Variety of Industries". Archived from the original on 2015-03-10. Retrieved 2015-03-12.

- "Careers". Archived from the original on 2015-04-08. Retrieved 2015-04-22.

- "Neuroscientist: Job Description, Duties and Requirements". Study.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-26. Retrieved 2016-03-29.

- "Medical Scientists : Occupational Outlook Handbook: : U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics". www.bls.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-03-25. Retrieved 2016-03-29.

- "Where Are the Neuroscience Jobs?". www.sciencemag.org. 2011-11-18. Archived from the original on 2016-03-17. Retrieved 2016-03-29.

- "What Should I Expect from a Neuroscience Job? (with pictures)". wiseGEEK. Archived from the original on 2016-04-16. Retrieved 2016-03-29.

- "Neuroscience College Degree Programs - The College Board". bigfuture.collegeboard.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-20. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- "How To Become A Cognitive Neuroscientist | CareersinPsychology.org". careersinpsychology.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-29. Retrieved 2016-03-29.

- "Cognitive & Behavioral Neuroscience". www.psychology.ucsd.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- "Computational neuroscience - Latest research and news | Nature". www.nature.com. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- Gross, Charles (1987). "Early History of Neuroscience" (PDF). Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03.

- McBean, Douglas (2012). Applied Neuroscience for the Allied Health Professions. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 2–3.

- Gross, Charles (1987). Neuroscience, Early History of. Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. pp. 843–847.

- Diamond, Adele; Amso, Dima (2008-04-01). "Contributions of Neuroscience to Our Understanding of Cognitive Development". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 17 (2): 136–141. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00563.x. ISSN 0963-7214. PMC 2366939. PMID 18458793.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2013". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1906 - Speed Read". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-23. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1932 - Speed Read". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1936 - Speed Read". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1944 - Speed Read". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- Sutherland, John (2004-08-02). "John Sutherland: Should they de-Nobel Moniz?". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1963 - Speed Read". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1970 - Speed Read". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1977". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1981". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1986 - Speed Read". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1991 - Speed Read". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2000 - Speed Read". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2004". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2014". Archived from the original on 2014-10-07.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2017". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

External links

- Interview with Nora Volkow, Director, National Institute on Drug Abuse. "Nora Volkow: Motivated Neuroscientist" in Molecular Interventions (2004) Volume 4, pages 243-247.

- Women in neuroscience research from the NIH Office of Science Education.

- To Become a Neuroscientist maintained by Eric Chudler at the University of Washington.