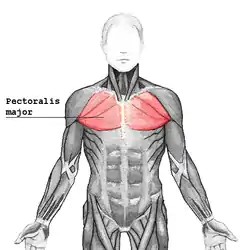

Pectoralis major

The pectoralis major (from Latin pectus 'breast') is a thick, fan-shaped or triangular convergent muscle, situated at the chest of the human body. It makes up the bulk of the chest muscles and lies under the breast. Beneath the pectoralis major is the pectoralis minor, a thin, triangular muscle. The pectoralis major's primary functions are flexion, adduction, and internal rotation of the humerus. The pectoral major may colloquially be referred to as "pecs", "pectoral muscle", or "chest muscle", because it is the largest and most superficial muscle in the chest area.

| Pectoralis major | |

|---|---|

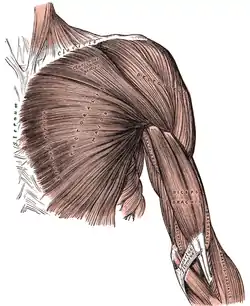

Superficial muscles of the chest and front of the arm | |

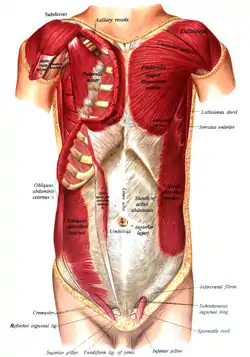

The trunk viewed from the front, showing the pectoralis major to the right (To the left it is removed showing underlying structures, among other the pectoralis minor.) | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /ˌpɛktəˈreɪlɪs ˈmeɪdʒər/ |

| Origin | Clavicular head: anterior surface of the medial half of the clavicle. Sternocostal head: anterior surface of the sternum, the superior six costal cartilages, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle |

| Insertion | Lateral lip of the bicipital groove of the humerus (anteromedial proximal humerus) |

| Artery | pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial trunk |

| Nerve | lateral pectoral nerve and medial pectoral nerve Clavicular head: C5 and C6 Sternocostal head: C7, C8 and T1 |

| Actions | Clavicular head: flexes the humerus

Sternocostal head: horizontal and vertical adduction, extension, and internal rotation of the humerus Depression and abduction of the scapula.[1] |

| Antagonist | Deltoid muscle, Trapezius |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Musculus pectoralis major |

| TA98 | A04.4.01.002 |

| TA2 | 2301 |

| FMA | 9627 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

Structure

It arises from the anterior surface of the sternal half of the clavicle from breadth of the half of the anterior surface of the sternum, as low down as the attachment of the cartilage of the sixth or seventh rib; from the cartilages of all the true ribs, with the exception, frequently, of the first or seventh, and from the aponeurosis of the abdominal external oblique muscle.[2][3]

From this extensive origin the fibers converge toward their insertion; those arising from the clavicle pass obliquely downward and outwards (laterally), and are usually separated from the rest by a slight interval; those from the lower part of the sternum, and the cartilages of the lower true ribs, run upward and laterally, while the middle fibers pass horizontally.

They all end in a flat tendon, about 5 cm in breadth, which is inserted into the lateral lip of the bicipital groove (intertubercular sulcus) of the humerus.

This tendon consists of two laminae, placed one in front of the other, and usually blended together below:

- The anterior lamina, which is thicker, receives the clavicular and the uppermost sternal fibers. They are inserted in the same order as that in which they arise: the most lateral of the clavicular fibers are inserted at the upper part of the anterior lamina; the uppermost sternal fibers pass down to the lower part of the lamina which extends as low as the tendon of the Deltoid and joins with it.

- The posterior lamina of the tendon receives the attachment of the greater part of the sternal portion and the deep fibers, i. e., those from the costal cartilages.

These deep fibers, and particularly those from the lower costal cartilages, ascend the humerus insertion higher, turning backward successively behind the superficial and upper ones, so that the tendon appears to be twisted. The posterior lamina reaches higher on the humerus than the anterior one, and from it an expansion is given off which covers the intertubercular groove of the humerus and blends with the capsule of the shoulder-joint.

From the deepest fibers of this lamina at its insertion an expansion is given off which lines the intertubercular groove, while from the lower border of the tendon a third expansion passes downward to the fascia of the arm.

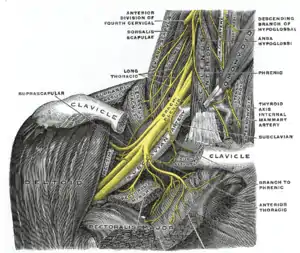

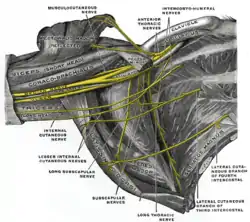

Nerve supply

The pectoralis major receives dual motor innervation by the medial pectoral nerve and the lateral pectoral nerve, also known as the lateral anterior thoracic nerve. The sternal head receives innervation from the C7, C8 and T1 nerve roots, via the lower trunk of the brachial plexus and the medial pectoral nerve. The clavicular head receives innervation from the C5 and C6 nerve roots via the upper trunk and lateral cord of the brachial plexus, which gives off the lateral pectoral nerve. The lateral pectoral nerve is distributed over the deep surface of the pectoralis major.

The sensory feedback from the pectoralis major follows the reverse path, returning via first-order neurons to the spinal nerves at C5, C6, C8, and T1 through the posterior rami.[4] After the synapse in the posterior horn of the spinal cord, sensory information concerning movement of the muscle, proprioception, and pressure then travels through a second-order neuron in the dorsal column medial lemniscus tract to the medulla. There, the fibers decussate to form the medial lemniscus which carries the sensory information the rest of the way to the thalamus, the "gateway to the cortex". The thalamus diverts some sensory information to the cerebellum and the basal nuclei to complete the motor feedback loop while some sensory information ascends directly to the postcentral gyrus of the parietal lobe of the brain via third-order neurons. Sensory information for the pectoralis major is processed in the superior portion of the sensory homunculus, adjacent to the longitudinal fissure which divides the two hemispheres of the brain.

Electromyography suggests that it consists of at least six groups of muscle fibres that can be independently coordinated by the central nervous system.[5]

Variation

The more frequent variations include greater or less extent of attachment to the ribs and sternum, varying size of the abdominal part or its absence, greater or less extent of separation of sternocostal and clavicular parts, fusion of clavicular part with deltoid, and decussation in front of the sternum. Deficiency or absence of the sternocostal part is not uncommon and more frequent than absence of the clavicular part. Poland syndrome is a rare congenital condition in which the whole muscle is missing, most commonly on one side of the body. This may accompany absence of the breast in females. The sternalis muscle may be a variant form of the pectoralis major or the rectus abdominis. [Submuscular and intramuscular surgical implants (similar to breast augmentation implants) may be available from plastic surgeons to modify aesthetic contours, mass, and asymmetry or variation in both males and females.[6]]

Function

The pectoralis major has four actions which are primarily responsible for movement of the shoulder joint.[7] The first action is flexion of the humerus, as in throwing a ball underhand, and in lifting a child. Secondly, it adducts the humerus, as when flapping the arms. Thirdly, it rotates the humerus medially, as occurs when arm-wrestling. Fourthly the pectoralis major is also responsible for keeping the arm attached to the trunk of the body.[7][8] It has two different parts which are responsible for different actions. The clavicular part is close to the deltoid muscle and contributes to flexion, horizontal adduction, and inward rotation of the humerus. When at an approximately 110 degree angle, it contributes to adduction of the humerus. The sternocostal part is antagonistic to the clavicular part contributing to downward and forward movement of the arm and inward rotation when accompanied by adduction. The sternal fibers can also contribute to extension, but not beyond anatomical position.[9]

Hypertrophy of the pectoralis major increases functionality. Maximal activation of the pectoralis major occurs in the transverse plane through pressing motions. Both multi-joint and single-joint exercises induce pectoralis major hypertrophy. A combination of both single-joint and multi-joint exercises will result in a maximum hypertrophic response. [Aesthetic contours of regions in the muscle may be specifically-addressed (“targeted”) by specific exercises; for instance, “plating” or “stitching” of the pectoralis major —towards the center of the sternum —-may be targeted by a wider hand position.] The pectoralis major can be targeted from numerous training angles along the sternum and clavicle.[10] Exercises that include horizontal adduction and elbow extensions such as the barbell bench press, dumbbell bench press, and machine bench press induce high activation of the pectoralis major in the sternocostal region. Heavy loads are strongly correlated with pectoralis major activation.[11]

Clinical significance

Injuries and imaging

_1232.jpg.webp)

Tears of the pectoralis major are rare and typically affect otherwise healthy individuals. This type of injury is known to affect the athletic population, namely in high-impact contact sports such as powerlifting, and may result in pain, weakness, and disability. Most lesions are located at the musculotendinous junction and result from violent, eccentric contraction of the muscle, such as during bench press.[12] A less frequent rupture site is the muscle belly, usually as a result of a direct blow. In developed countries, most lesions occur in male athletes, especially those practicing contact sports and weight-lifting (particularly during a bench press maneuver). Women are less susceptible to these tears because of larger tendon-to-muscle diameter, greater muscular elasticity, and less energetic injuries.[13] The injury is characterized by sudden and acute pain in the chest wall and shoulder area, bruising and loss of strength of the muscle. High grade partial or full thickness tears warrant surgical repair as the preferred treatment if function is to be preserved, particularly in the athletic population.

Acting fast, obtaining the correct diagnoses, and getting the surgical repair as soon as possible is a key to successful recovery. Waiting can cause the acute injury to become chronic and chances of success is greatly diminished as a result. After surgery, the impacted arm is then immobilized with a sling for about six to eight weeks to minimize and avoid movement of the arm and potentially re-rupturing the surgery site. About two months after the surgery, physical therapy is typically introduced for about six months, after which point strengthening of the muscle is needed to achieve good results. Most patients are able to return to activity after six months to a year following surgery with high patient satisfaction and slightly reduced strength compared to pre-injury.[12] Both US[14] and MRI[15] are useful to confirm the diagnosis, location and extent of a tear, though the first may be more cost-effective in experienced hands.

Poland syndrome

Poland syndrome is a congenital anomaly in which there is a malformation of the chest causing the pectoralis major on one side of the body to be absent. Other characteristics of this disease are "unilateral shortening of the index, long, and ring fingers, syndactyly of the affected digits, hypoplasia of the hand, and the absence of the sternocostal portion of the ipsilateral pectoralis major muscle".[16] Although the absence of a pectoralis major is not life-threatening, it will have an effect on the person with Poland's syndrome. Adduction and medial rotation of the arm will be much harder to accomplish without the pectoralis major. The latissimus dorsi and teres major also aid in adduction and medial rotation of the arm, so they may be able to compensate for the lack of extra muscle. However, some patients with Poland's syndrome may also be lacking these muscles, which make these actions nearly impossible.

Researchers from the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine at the Yonsei University College of Medicine in Seoul, Korea reported a case of congenital absence of pectoralis major in 1990. According to Kakulas and Adams, pectoralis major is the most frequently congenitally absent muscle. The case involved a 22-year-old marine who had asymmetrical configuration of chest wall who had never experienced difficulties performing daily activities, but who experienced difficulties in the military camp. He had difficulty in some training activities especially those such as throwing a grenade or rope climbing. During a surgery performed to correct the sternal depression, it was found that the right pectoralis major was totally absent. However, previous physical exams did not show deficiencies in muscle strength as the right shoulder was good for flexion, adduction, horizontal adduction and internal rotation. Moreover, his pain and touch sensation were normal. X-rays were also performed and showed normal pictures of the chest's bones. The fact that the absence of pectoralis major did not cause functional loss in ordinary activities in this case of congenital absence showed that other surrounding muscles played a compensatory role.[17]

Other diseases

Pectoralis major muscle in rare occasions may develop intramuscular lipomas. Such rare tumors may mimic malignant breast tumors as they look like enlargements of the breasts. They are well-encapsulated radiolucent tumours of fat density. Their location can be accurately identified through computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The treatment in these cases involves complete surgical excision because of the risk of liposarcoma they post especially large intramuscular liposomas. Partial excision is risky because recurrence may occur.[18]

Additional images

Pectoralis major highlighted on the trunk – frontal view

Pectoralis major highlighted on the trunk – frontal view Anterior surface of sternum and costal cartilages, showing origins

Anterior surface of sternum and costal cartilages, showing origins Left clavicle. Superior surface, showing origins.

Left clavicle. Superior surface, showing origins. Left clavicle. Inferior surface, showing origins.

Left clavicle. Inferior surface, showing origins. Left humerus. Anterior view, showing insertion.

Left humerus. Anterior view, showing insertion. The axillary artery and its branches

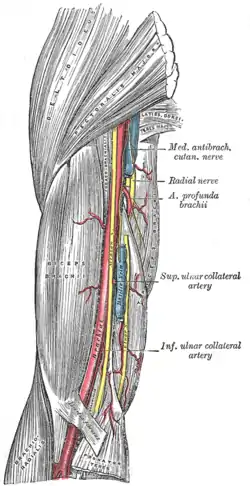

The axillary artery and its branches The brachial artery

The brachial artery The right brachial plexus with its short branches, viewed from in front

The right brachial plexus with its short branches, viewed from in front The right brachial plexus (infraclavicular portion) in the axillary fossa; viewed from below and in front

The right brachial plexus (infraclavicular portion) in the axillary fossa; viewed from below and in front Nerves of the left upper extremity

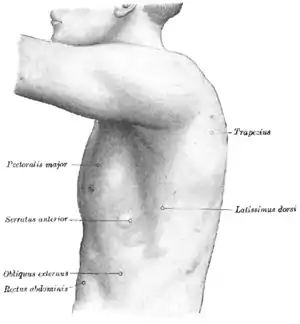

Nerves of the left upper extremity The left side of the thorax

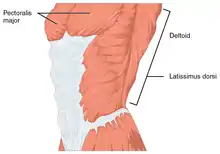

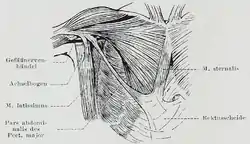

The left side of the thorax Pectoralis major muscle

Pectoralis major muscle An individual with an abdominal portion of the pectoralis major, and an accessory sternalis muscle. Both these are anatomical variations.

An individual with an abdominal portion of the pectoralis major, and an accessory sternalis muscle. Both these are anatomical variations.

See also

- Pectoralis minor, an inferior, smaller muscle to the pectoralis major

- Sternalis, an accessory muscle found in some individuals that may have embryonic origin from the pectoralis major

- Tra Telligman, a retired American mixed martial artist and boxer having only one pectoral muscle

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 436 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 436 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Pectoralis Major (Sternal Head). "PectoralisSternal". ExRx. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Pectoralis Major". University of Washington - Dept. of Radiology. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- "Pectoralis Muscle". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- "Pectoralis Major". Washington University School of Medicine. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- Brown, JM; Wickham, JB; McAndrew, DJ; Huang, XF (2007). "Muscles within muscles: Coordination of 19 muscle segments within three shoulder muscles during isometric motor tasks". J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 17 (1): 57–73. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2005.10.007. PMID 16458022.

- "Hi Def Pectoral Augmentation for Men in New York | ✓Best Results".

- Saladin, KS (2010). Anatomy & Physiology: The Unit of Form and Function. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. Changes made by Kari Thomas.

- Hamilton, N, Luttgens, K, Weimar, W (2008). Kinesiology. 11th ed. Boston: Mcgraw Hill. Changes made by Kari Thomas

- ExRx: Pectoralis Major Sternal

- Schoenfeld, Brad (2016). The Science and Development of Muscle Hypertrophy. United States of America: Human Kinetics. p. 120. ISBN 978-1492519607.

- "Pectoralis major". Strength & Conditioning Research. 2015-07-16. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- Garrigues, GE; Kraeutler, MJ; Gillespie, RJ; O'Brien, DF; Lazarus, MD (2012). "Repair of pectoralis major ruptures: single-surgeon case series". Orthopedics. 35 (8): e1184–1190. doi:10.3928/01477447-20120725-17. PMID 22868603.

- Aarimaa, V; Rantanen, J; Heikkila, J; Helttula, I; Orava, S (2004). "Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle". Am J Sports Med. 32 (5): 1256–62. doi:10.1177/0363546503261137. PMID 15262651. S2CID 20216563.

- Arend CF. Ultrasound of the Shoulder. Master Medical Books, 2013. Chapter on ultrasound evaluation of pectoralis major tears available at ShoulderUS.com

- Connell DA, Sherman MF, Wickiewicz TL (1999). "Injuries of the pectoralis major muscle: evaluation with MR imaging". Radiology. 210 (3): 785–91. doi:10.1148/radiology.210.3.r99fe43785. PMID 10207482.

- www.polands-syndrome.com Archived 2011-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- "Congenital Absence of Pectoralis Major: A Case Report and Isokinetic Analysis of Shoulder Motion" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- "An Unusual Case of an Intramuscular Lipoma of the Pectoralis Major Muscle Simulating a Malignant Breast Mass" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-07-13.

External links

- Illustration: upper-body/pectoralis-major from The Department of Radiology at the University of Washington

- UCC

- www.polands-syndrome.com

- MRI Imaging sequence demonstrating a pectoralis major muscle tear