Permanent makeup

Permanent makeup is a cosmetic technique which employs tattoos (permanent pigmentation of the dermis) as a means of producing designs that resemble makeup, such as eye-lining and other permanent enhancing colors to the skin of the face, lips, and eyelids. It is also used to produce artificial eyebrows, particularly in people who have lost them as a consequence of old age, disease, such as alopecia totalis, chemotherapy, or a genetic disturbance, and to disguise scars and hypopigmentation in the skin such as in vitiligo.[1] It is also used to restore or enhance the breast's areola, such as after breast surgery.

Most commonly called permanent cosmetics, other names include derma-pigmentation, micro-pigmentation, and cosmetic tattooing,[2] the latter being most appropriate since permanent makeup is applied under sterile conditions similar to that of a tattoo.[3] In the United States the inks used in permanent makeup are subject to approval as cosmetics by the Food and Drug Administration. The pigments used in the inks are color additives, which are subject to pre-market approval under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.[4] However, because of other competing public health priorities in the United States and a previous lack of evidence of safety problems specifically associated with these pigments, FDA traditionally has not exercised regulatory authority for color additives on the pigments used in tattoo inks.[5]

History

The first documented permanent makeup treatment was done by the famous U.K. tattoo artist Sutherland MacDonald[6] in 1902 at his parlor, #76 Jermyn Str., London, "all-year-round delicate pink complexion" on the cheeks. In 1920s this "London fad" crossed the Atlantic, and the "electrically tattoing [sic?] a permanent complexion or blush on the face" became popular in the USA. The tattooist George Burchett, a major developer of the technique when it became fashionable in the 1930s, described in his memoirs how beauty salons tattooed many women without their knowledge, offering it as a "complexion treatment ... of injecting vegetable dyes under the top layer of the skin."[7][8]

Results

Long-term results

The best possible colour results can perform for many years or may begin to fade over time. The amount of time required for this depends per person. While permanent makeup pigment remains in the dermis, its beauty-span may be influenced by several possible factors, including environmental, procedural and/or individual factors.[9] Sun exposure fades colour. The amount and colour of pigment deposit at the dermal level can affect the length of time that permanent makeup looks its best. Very natural-looking applications are likely to require a touch-up before more dramatic ones for this reason. Individual influences include lifestyles that find an individual in the sun regularly, such as with gardening or swimming. Skin tones are a factor in colour value changes over time.

Imperfections

There are cases of undesired results.[10]

Removal

As with tattoos, permanent makeup can be difficult to remove. Common techniques used for this are laser resurfacing, dermabrasion (physical or chemical exfoliation), and surgical removal.

Adverse effects and complications

As with tattoos, permanent makeup may have complications, such as migration, allergies to the pigments, formation of scars, granulomas and keloids, skin cracking, peeling, blistering and local infection.[11] The use of unsterilized tattooing instruments may infect the patient with serious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis. Removal problems may also ensue, due to patient dissatisfaction or regret, and they may be particularly difficult to remove in places such as eyelids and lips without leaving permanent sequelae. Compliance with 'standard precautions' and a uniform code of safe practice should be insisted upon by a person considering undergoing a cosmetic tattoo procedure.[12][13]

It is essential that technicians use appropriate personal protective equipment to protect the health of the technician and the client particularly in the prevention of transmission of blood borne pathogens.[14]

It is also essential that technicians have been properly trained in the application of pigment into the skin to avoid migration. Tattoo pigments can "migrate" when a technician "overworks" an area, especially around the eyes where the pigment can "bleed" into surrounding tissue. Migration is generally avoidable by not over-working swollen tissue. Understanding the need to minimize swelling and recognize a good stopping point is paramount to successful application. Removing migrated pigment is a difficult and complicated process.

On very rare occasions, people with permanent makeup have reported swelling or burning in the affected areas when they underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[15] However a detailed review of the cases within the medical literature involving cosmetic tattoos indicates that poor quality pigments, pigments adulterated with heavy metals, and pigments with diamagnetic properties may have been the causative factors in most of those cases.[16][17]

Topical anaesthetics are often used by technicians prior to cosmetic tattooing and there is the potential for adverse effects if topical anaesthetics are not used safely. In 2013 the International Industry association CosmeticTattoo.org published a detailed position and general safety precautions for the entire industry.[18]

The causes of a change of colour after cosmetic tattooing are both complex and varied. As discussed in the detailed industry article "Why Do Cosmetic Tattoos Change Colour",[19] primarily there are four main areas that have influence over the potential for a cosmetic tattoo to change colour;

- Factors related to the pigment characteristics

- Factors related to the methods and techniques of the tattooist

- Factors intrinsic to the client

- Factors related to the client's environment and medicines

Examples

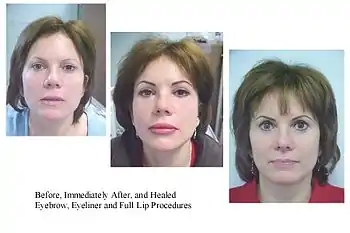

The eyebrow tattooing is an example of a "powdery filled" technique as opposed to individual hairline strokes since the client already has eyebrow hair but simply wanted an enhancement and shaping. The top eyeliner represents a thin eyeliner tattoo and a "lash enhancement" procedure that is used to define the eye without making it look excessively made up.

See also

- Microblading

- Hair tattoo

References

- De Cuyper, Christa (2008-01-01). "Permanent makeup: indications and complications". Clinics in Dermatology. 26 (1): 30–34. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.10.009. ISSN 0738-081X.

- Industry Profile Study: Vision 2009

- "Permanent Makeup (Micropigmentation): Get Facts About Risk". MedicineNet. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

- Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied. "Products - Tattoos & Permanent Makeup: Fact Sheet". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

- Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied (11 September 2020). "Products - Tattoos & Permanent Makeup: Fact Sheet". www.fda.gov.

- "The man who started the tattoo craze in Britain is coming to a museum near you". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2022-05-25. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

- Revolting Bodies: The Monster Beauty of Tattooed Women, Christine Braunberger, NWSA Journal Volume 12, Number 2

- "Lip Tattooing Is the Latest Fad". Moder Mechanix. January 1933. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- "Guidelines – Semi-Permanent Makeup - Society for Permanent Cosmetic, Micropigmentation, Permanent Makeup, Microblading and Cosmetic Tattoo Professionals". www.spcp.org.

- FDA on Tattoos and Permanent Makeup

- "FDA: Tattoo Pigment Recalls".

- "Members Code of Ethics & Conduct". CosmeticTattoo.org.

- "SPCP Code of Ethics - Society for Permanent Cosmetic, Micropigmentation, Permanent Makeup, Microblading and Cosmetic Tattoo Professionals". www.spcp.org.

- "Personal Protective Equipment - Are You Covered?". CosmeticTattoo.org.

- Franiel, Tobias; Schmidt, Sein; Klingebiel, Randolf (1 November 2006). "First-Degree Burns on MRI due to Nonferrous Tattoos". American Journal of Roentgenology. 187 (5): W556. doi:10.2214/ajr.06.5082. PMID 17056894.

- "Cosmetic Tattooing & MRI's - Diametric Particle Agitation Hypothesis (DPA)". CosmeticTattoo.org.

- SPCP Research into Tattooing and MRIs Archived 2014-07-26 at the Wayback Machine

- "Topical Anaesthetics & Cosmetic Procedures". CosmeticTattoo.org.

- "Why Do Cosmetic Tattoos Change Colour? - Part 1". CosmeticTattoo.org.

External links

![]() Media related to Permanent makeup at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Permanent makeup at Wikimedia Commons

- FDA: Tattoos and Permanent Makeup

- FDA: Think Before You Ink – Are Tattoos Safe?

- Paola Piccinini, Laura Contor, Ivana Bianchi, Chiara Senaldi, Sazan Pakalin: Safety of tattoos and permanent make-up, Joint Research Centre, 2016, ISBN 978-92-79-58783-2, doi:10.2788/011817.