Pissoir

A pissoir (also known in French as a vespasienne) is a French invention, common in Europe, that provides a urinal in public space with a lightweight structure. The availability of pissoirs aims to reduce urination onto buildings, sidewalks, or streets.[1] They can be freestanding and without screening, with partial screening, or fully enclosed.

History

In the spring of 1830, the city government of Paris decided to install the first public urinals on the major boulevards. They were put in place by the summer, but in July of the same year, many were destroyed through their use as materials for street barricades during the French Revolution of 1830.[2]

The urinals were re-introduced in Paris after 1834, when over 400 were installed by Claude-Philibert Barthelot, comte de Rambuteau, the Préfet of the Départment of the Seine. Having a simple cylindrical shape, built of masonry, open on the street side, and ornately decorated on the other side as well as the cap, they were popularly known as 'colonnes Rambuteau' ('Rambuteau columns'). In response, Rambuteau suggested the name 'vespasiennes',[3] in reference to the 1st century Roman emperor Titus Flavius Vespasianus, who placed a tax on urine collected from public toilets for use in tanning. This is the usual term by which street urinals are known in the French speaking world, although 'pissoir' and 'pissotière' are also in common use.

In Paris, the next version was a masonry column that allowed for the pasting of posters on the side facing the footpath, creating a tradition that continues to this day (as a Morris column, a column with an elaborate roof and without the urinal).

Cast iron urinals were developed in the United Kingdom, with the Scottish firm of Walter McFarlane and Company casting urinals at their Saracen Foundry and erecting the first at Paisley Road, Glasgow in October 1850. By the end of 1852, nearly 50 cast iron urinals had been installed in Glasgow, including designs with more than one stall.[4] Unlike Rambuteau's columns, which were entirely open at the front, McFarlane's one-man urinals were designed with spiral cast iron screens that allowed the user to be hidden from sight, and his multi-stall urinals were completely hidden within ornate, modular cast iron panels. Three manufacturers in Glasgow, Walter Macfarlane & Co., George Smith (Sun Foundry) and James Allan Snr & Son (Elmbank Foundry), supplied the majority of cast iron urinals across Britain[4] and exported them around the world, including Australia and Argentina.[5]

Back in Paris, cast iron urinals were introduced as part of Baron Haussmann's remodelling of the city. A large variety of designs were produced in subsequent decades, housing two to 8 stalls, typically only screening the central portion of the user from public view, with the head and feet still visible. Screens were also added to Rambuteau columns. At the peak of their spread in the 1930s there were 1,230 pissoirs in Paris, but by 1966 their number had decreased to 329. From 1980 they were replaced systematically with new technology, a unisex, enclosed, automatically self-cleaning unit called the Sanisette.[6] By 2006, only one historic pissoir remained, on Boulevard Arago.[7]

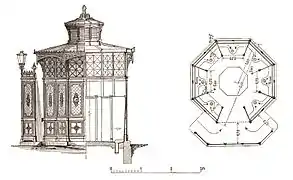

In Berlin, the first pissoirs, in wood, were erected in 1863. In order to provide a design as distinguished as in other cities, several architectural design competitions were organised in 1847, 1865 and 1877. The last design, proposed by a city councillor, was the one adopted in 1878, a cast-iron octagonal structure with seven stalls and a peaked roof, known locally as a Café Achteck ('Octagon Cafe'). In common with British designs, they provided complete enclosure, and were provided with interior lighting. Their number increased to 142 by 1920,[8] but there are now only about a dozen remaining in use.[9]

A similar design was adopted in Vienna, though simpler, smaller and hexagonal. They were equipped with a novel "oil system", patented by Wilhelm Beetz in 1882, where a type of oil was used to neutralise odours, dispensing with the necessity for plumbing.[10] About 15 are still in use, and one has been restored and set up as a display in the Vienna Technical Museum.[11]

In central Amsterdam, there are about 35 pee curls, which consist of a raised metal screen that curls in a spiral enclosing a single urinal stall, including some two-person examples with the same details but a simpler shape. Though the design first emerged in the 1870s, an updated design by Joan van der Mey dates from 1916. All the remaining examples were restored in 2008.

Pissoirs of various sizes and designs, but mostly in patterned cast-iron, can still be found dotted across the UK, with a few in London, but especially in Birmingham and Bristol. A solitary example of Walter McFarlane's one-man spiral urinal remains in Thorn Park, Plymouth.[12] A number have been restored and relocated to the grounds of various open-air museums and heritage railway lines.[12]

Rectangular pissoirs, with elaborate patterned cast-iron panels, similar in design to some of the UK ones, were installed in the city of Sydney, Australia in 1880[13] and Melbourne, Australia, in the period 1903–1918. Of at least 40 that were made, nine remain in place and in use on the streets in and around central Melbourne, and have been classified by the National Trust since 1998.[14]

In recent years, temporary pissoirs with multiple unscreened urinals around a central column have been introduced in the UK.[15][16] A temporary pissoir for women called the 'Peeasy' is used in Switzerland.[17]

In popular culture

A pissoir was featured in the first scene of the 1967 James Bond spoof film Casino Royale.[1]

A pissoir was also featured in a few episodes of the British WWII comedy series 'Allo 'Allo!, as a meeting place for René Artois (Nighthawk) and other members of the Resistance, and is accidentally blown up a few times, twice while Officer Crabtree is inside, and once with the Italian Captain Alberto Bertorelli.

In episode 22 of Season 2 of Two and a Half Men, "That Old Hose Bag Is My Mother", Alan's mother invites him to dinner at a restaurant called "Le Pissoir".

Clochemerle, broadcast in the UK in 1972, starring Peter Ustinov and many others, depicts a rural French town's attempts to erect a public urinal.

In the season one third episode of Emily in Paris the main character tries to show off the view from the Seine to her American boss only to accidentally film a man using a pissoir.

Plaskruis

A plaskruis is a pissoir designed in the Netherlands that is the same size as a portable toilet and provides four urinals per unit. They are not connected to the sewer system but have their own storage tank. They are commonly used for music festivals and other events, but some cities also use them on a regular basis to control public urination during busy nights. It was designed by Joost Carlier who works for Lowlands and other events. They were first used in 1991 during the "Monsters Of Rock" event in the Goffertpark.

Gallery

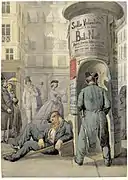

'Colonnes Rambuteau', Paris, c. 1860

'Colonnes Rambuteau', Paris, c. 1860 'Colonnes Rambuteau' with screen, Paris, c. 1865

'Colonnes Rambuteau' with screen, Paris, c. 1865 A pissoir with three stalls, Paris, c. 1865

A pissoir with three stalls, Paris, c. 1865 Vespasienne Arago, the only surviving Parisian pissoir.

Vespasienne Arago, the only surviving Parisian pissoir. Elevation, section and plan drawings of an octagonal pissoir in Berlin, 1896

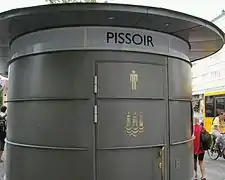

Elevation, section and plan drawings of an octagonal pissoir in Berlin, 1896 Cafe Achteck, Berlin, converted to male and female toilets

Cafe Achteck, Berlin, converted to male and female toilets Amsterdam 'Plaskrul'

Amsterdam 'Plaskrul'_1923.jpg.webp) Brick pissoir, Deventer, Arnhem, Netherlands, 1923

Brick pissoir, Deventer, Arnhem, Netherlands, 1923 Pissoir, Hütteldorf, Vienna, 1936

Pissoir, Hütteldorf, Vienna, 1936 A pissoir close to the royal castle in Gamla Stan, Stockholm, Sweden

A pissoir close to the royal castle in Gamla Stan, Stockholm, Sweden%252C_2011%252C_Urinol._(5925305117).jpg.webp) Pissoir in Lisbon

Pissoir in Lisbon Historic cast-iron urinal at Colyford station, England

Historic cast-iron urinal at Colyford station, England Cast iron urinal Melbourne

Cast iron urinal Melbourne Pissoir in Copenhagen

Pissoir in Copenhagen A retractable pissoir in The Hague

A retractable pissoir in The Hague Plaskruis in London

Plaskruis in London MMDA street urinal in Pateros, Metro Manila, Philippines

MMDA street urinal in Pateros, Metro Manila, Philippines

See also

- Clochemerle (1934), a comic novel

Notes

- Jaggard, David (27 March 2012). "The Flow of History: The Mercifully Dwindling Presence of the Parisian Pissoir". Paris Update. Archived from the original on 20 July 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- Fierro 1996, p. 1177.

- Pike 2005, p. 234.

- Kearney, Peter (1985). The Glasgow Cludgie. Newcastle: People's Publications. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0906917145.

- Juarez, Lucia (2014-12-01). "Documenting Scottish Architectural Cast Iron in Argentina". ABE Journal (5). doi:10.4000/abe.821. ISSN 2275-6639.

- Ress 2006.

- Bärthel, Hilmar (2000): "Tempel aus Gusseisen: Urinale, Café Achteck und Vollanstalten", Berlinische Monatsschrift Heft 11

- "Café Achteck - Berlin's Green Pissoir". Berlin Love. 2017-11-13. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

- "Wiens letzte Öl-Klos werden saniert". wien.orf.at (in German). 2017-11-14. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

- "Wiener Pavillon Pissoir, 1908 – Technisches Museum Wien". www.technischesmuseum.at. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

- "street urinals". HERITAGE GROUP WEBSITE for the CHARTERED INSTITUTION of BUILDING SERVICES ENGINEERS. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

- "Cast Iron Urinal | Heritage NSW". apps.environment.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 2021-05-18.

- "Cast Iron Street Urinals - Group". Victorian Heritage Database.

- "The Pee Pod - the place to pee in Milton Keynes!". BBC News, 15 June 2010.

- "Edinburgh to trial 'pee pod' street urinals". BBC News, 24 November 2010.

- Salzmann, Claudia. "Frauen-Pissoir: Kein leichtes Unterfangen". Berner Zeitung, 18 July 2011 (in German).

Bibliography

- Fierro, Alfred (1996). Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris. Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221-07862-4.

- Pike, David L. (2005). Subterranean Cities: The World Beneath Paris and London, 1800-1945. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-801-47256-5.

- Ress, Paul (2006). "The Vanashing Vespasienne". Shaggy Dog Tales: 58 1/2 Years of Reportage. Xlibris. pp. 49–51. ISBN 978-1-450-09805-2.

External links

Clochemerle at IMDb