Post-traumatic seizure

Post-traumatic seizures (PTS) are seizures that result from traumatic brain injury (TBI), brain damage caused by physical trauma. PTS may be a risk factor for post-traumatic epilepsy (PTE), but a person having a seizure or seizures due to traumatic brain injury does not necessarily have PTE, which is a form of epilepsy, a chronic condition in which seizures occur repeatedly. However, "PTS" and "PTE" may be used interchangeably in medical literature.[1]

Seizures are usually an indication of a more severe TBI.[1] Seizures that occur shortly after a person sustains a brain injury may further damage the already vulnerable brain.[2] They may reduce the amount of oxygen available to the brain,[3] cause excitatory neurotransmitters to be released in excess, increase the brain's metabolic need, and raise the pressure within the intracranial space, further contributing to damage.[2] Thus, people who sustain severe head trauma are given anticonvulsant medications as a precaution against seizures.[3]

Around 5–7% of people hospitalized with TBI have at least one seizure.[4] PTS are more likely to occur in more severe injuries, and certain types of injuries increase the risk further. The risk that a person will develop PTS becomes progressively lower as time passes after the injury. However, TBI survivors may still be at risk over 15 years after the injury.[5] Children and older adults are at a higher risk for PTS.

Classification

In the mid-1970s, PTS was first classified by Bryan Jennett into early and late seizures, those occurring within the first week of injury and those occurring after a week, respectively.[6] Though the seven-day cutoff for early seizures is used widely, it is arbitrary; seizures occurring after the first week but within the first month of injury may share characteristics with early seizures.[7] Some studies use a 30‑day cutoff for early seizures instead.[8] Later it became accepted to further divide seizures into immediate PTS, seizures occurring within 24 hours of injury; early PTS, with seizures between a day and a week after trauma; and late PTS, seizures more than one week after trauma.[9] Some consider late PTS to be synonymous with post-traumatic epilepsy.[10]

Early PTS occur at least once in about 4 or 5% of people hospitalized with TBI, and late PTS occur at some point in 5% of them.[9] Of the seizures that occur within the first week of trauma, about half occur within the first 24 hours.[11] In children, early seizures are more likely to occur within an hour and a day of injury than in adults.[12] Of the seizures that occur within the first four weeks of head trauma, about 10% occur after the first week.[5] Late seizures occur at the highest rate in the first few weeks after injury.[7] About 40% of late seizures start within six months of injury, and 50% start within a year.[11]

Especially in children and people with severe TBI, the life-threatening condition of persistent seizure called status epilepticus is a risk in early seizures; 10 to 20% of PTS develop into the condition.[11] In one study, 22% of children under 5 years old developed status seizures, while 11% of the whole TBI population studied did.[12] Status seizures early after a TBI may heighten the chances that a person will develop unprovoked seizures later.[11]

Pathophysiology

It is not completely understood what physiological mechanisms cause seizures after injury, but early seizures are thought to have different underlying processes than late ones.[13] Immediate and early seizures are thought to be a direct reaction to the injury, while late seizures are believed to result from damage to the cerebral cortex by mechanisms such as excitotoxicity and iron from blood.[2] Immediate seizures occurring within two seconds of injury probably occur because the force from the injury stimulates brain tissue that has a low threshold for seizures when stimulated.[14] Early PTS are considered to be provoked seizure, because they result from the direct effects of the head trauma and are thus not considered to be actual epilepsy, while late seizures are thought to indicate permanent changes in the brain's structure and to imply epilepsy.[11] Early seizures can be caused by factors such as cerebral edema, intracranial hemorrhage, cerebral contusion or laceration.[14] Factors that may result in seizures that occur within two weeks of an insult include the presence of blood within the brain; alterations in the blood brain barrier; excessive release of excitatory neurotransmitters such as glutamate; damage to tissues caused by free radicals; and changes in the way cells produce energy.[13] Late seizures are thought to be the result of epileptogenesis, in which neural networks are restructured in a way that increases the likelihood that they will become excited, leading to seizures.[13]

Diagnosis

Medical personnel aim to determine whether a seizure is caused by a change in the patient's biochemistry, such as hyponatremia.[2] Neurological examinations and tests to measure levels of serum electrolytes are performed.[2]

Not all seizures that occur after trauma are PTS; they may be due to a seizure disorder that already existed, which may even have caused the trauma.[15] In addition, post-traumatic seizures are not to be confused with concussive convulsions, which may immediately follow a concussion but which are not actually seizures and are not a predictive factor for epilepsy.[16]

Neuroimaging is used to guide treatment. Often, MRI is performed in any patient with PTS, but the less sensitive but more easily accessed CT scan may also be used.[17]

Prevention

Shortly after TBI, people are given anticonvulsant medication, because seizures that occur early after trauma can increase brain damage through hypoxia,[3] excessive release of excitatory neurotransmitters, increased metabolic demands, and increased pressure within the intracranial space.[2] Medications used to prevent seizures include valproate, phenytoin, and phenobarbital.[18] It is recommended that treatment with anti-seizure medication be initiated as soon as possible after TBI.[8] Prevention of early seizures differs from that of late seizures, because the aim of the former is to prevent damage caused by the seizures, whereas the aim of the latter is to prevent epileptogenesis.[3] Strong evidence from clinical trials suggests that antiepileptic drugs given within a day of injury prevent seizures within the first week of injury, but not after.[4] For example, a 2003 review of medical literature found phenytoin to be preventative of early, but probably not late PTS.[7] In children, anticonvulsants may be ineffective for both early and late seizures.[4] For unknown reasons, prophylactic use of antiepileptic drugs over a long period is associated with an increased risk for seizures.[1] For these reasons, antiepileptic drugs are widely recommended for a short time after head trauma to prevent immediate and early, but not late, seizures.[1][19] No treatment is widely accepted to prevent the development of epilepsy.[3] However, medications may be given to repress more seizures if late seizures do occur.[18]

Treatment

Seizures that result from TBI are often difficult to treat.[13] Antiepileptic drugs that may be given intravenously shortly after injury include phenytoin, sodium valproate, carbamazepine, and phenobarbital.[2] Antiepileptic drugs do not prevent all seizures in all people,[5] but phenytoin and sodium valproate usually stop seizures that are in progress.[2]

Prognosis

PTS is associated with a generally good prognosis.[14] It is unknown exactly how long after a TBI a person is at higher risk for seizures than the rest of the population, but estimates have suggested lengths of 10 to over 15 years.[5] For most people with TBI, seizures do not occur after three months, and only 20–25% of people with TBI have PTS more than two years after the injury.[9] However, moderate and severe TBI still confer a high risk for PTS for up to five years after the injury.[4]

Studies have reported that 25–40% of PTS patients go into remission; later studies conducted after the development of more effective seizure medications reported higher overall remission rates.[5] In one quarter of people with seizures from a head trauma, medication controls them well.[1] However, a subset of patients have seizures despite aggressive antiepileptic drug therapy.[5] The likelihood that PTS will go into remission is lower for people who have frequent seizures in the first year after injury.[5]

Risk of developing PTE

It is not known whether PTS increase the likelihood of developing PTE.[13] Early PTS, while not necessarily epileptic in nature, are associated with a higher risk of PTE.[20] However, PTS do not indicate that development of epilepsy is certain to occur,[21] and it is difficult to isolate PTS from severity of injury as a factor in PTE development.[13] About 3% of patients with no early seizures develop late PTE; this number is 25% in those who do have early PTS, and the distinction is greater if other risk factors for developing PTE are excluded.[21] Seizures that occur immediately after an insult are commonly believed not to confer an increased risk of recurring seizures, but evidence from at least one study has suggested that both immediate and early seizures may be risk factors for late seizures.[5] Early seizures may be less of a predictor for PTE in children; while as many as a third of adults with early seizures develop PTE, the portion of children with early PTS who have late seizures is less than one fifth in children and may be as low as one tenth.[12] The incidence of late seizures is about half that in adults with comparable injuries.[12]

Epidemiology

Research has found that the incidence of PTS varies widely based on the population studied; it may be as low as 4.4% or as high as 53%.[5] Of all TBI patients who are hospitalized, 5 to 7% have PTS.[4] PTS occur in about 3.1% of traumatic brain injuries, but the severity of injury affects the likelihood of occurrence.[9]

The most important factor in whether a person will develop early and late seizures is the extent of the damage to the brain.[2] More severe brain injury also confers a risk for developing PTS for a longer time after the event.[4] One study found that the probability that seizures will occur within 5 years of injury is in 0.5% of mild traumatic brain injuries (defined as no skull fracture and less than 30 minutes of post-traumatic amnesia, abbreviated PTA, or loss of consciousness, abbreviated LOC); 1.2% of moderate injuries (skull fracture or PTA or LOC lasting between 30 minutes and 24 hours); and 10.0% of severe injuries (cerebral contusion, intracranial hematoma, or LOC or PTA for over 24 hours).[23] Another study found that the risk of seizures 5 years after TBI is 1.5% in mild (defined as PTA or LOC for less than 30 minutes), 2.9% in moderate (LOC lasting between 30 minutes and 1 day), and 17.2% in severe TBI (cerebral contusion, subdural hematoma, or LOC for over a day; image at right).[2][11]

Immediate seizures have an incidence of 1 to 4%, that of early seizures is 4 to 25%, and that of late seizures is 9 to 42%.[2]

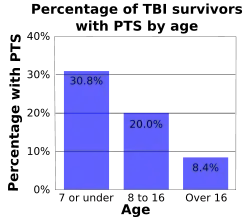

Age influences the risk for PTS. As age increases, risk of early and late seizures decreases; one study found that early PTS occurred in 30.8% of children age 7 or under, 20% of children between ages 8 and 16, and 8.4% of people who were over 16 at the time they were injured (graph at right).[5][22] Early seizures occur up to twice as frequently in brain injured children as they do in their adult counterparts.[5] In one study, children under five with trivial brain injuries (those with no LOC, no PTA, no depressed skull fracture, and no hemorrhage) had an early seizure 17% of the time, while people over age 5 did so only 2% of the time.[5] Children under age five also have seizures within one hour of injury more often than adults do.[11] One study found the incidence of early seizures to be highest among infants younger than one year and particularly high among those who sustained perinatal injury.[14] However, adults are at higher risk than children are for late seizures.[24] People over age 65 are also at greater risk for developing PTS after an injury, with a PTS risk that is 2.5 times higher than that of their younger counterparts.[25]

Risk factors

The chances that a person will develop PTS are influenced by factors involving the injury and the person. The largest risks for PTS are having an altered level of consciousness for a protracted time after the injury, severe injuries with focal lesions, and fractures.[8] The single largest risk for PTS is penetrating head trauma, which carries a 35 to 50% risk of seizures within 15 years.[2] If a fragment of metal remains within the skull after injury, the risk of both early and late PTS may be increased.[5] Head trauma survivors who abused alcohol before the injury are also at higher risk for developing seizures.[4]

Occurrence of seizures varies widely even among people with similar injuries.[5] It is not known whether genetics play a role in PTS risk.[11] Studies have had conflicting results with regard to the question of whether people with PTS are more likely to have family members with seizures, which would suggest a genetic role in PTS.[11] Most studies have found that epilepsy in family members does not significantly increase the risk of PTS.[5] People with the ApoE-ε4 allele may also be at higher risk for late PTS.[1]

Risks for late PTS include hydrocephalus, reduced blood flow to the temporal lobes of the brain,[1] brain contusions, subdural hematomas,[5] a torn dura mater, and focal neurological deficits.[9] PTA that lasts for longer than 24 hours after the injury is a risk factor for both early and late PTS.[1] Up to 86% of people who have one late post-traumatic seizure have another within two years.[5]

References

- Tucker GJ (2005). "16: Seizures". In Silver JM, McAllister TW, Yudofsky SC (eds.). Textbook Of Traumatic Brain Injury. American Psychiatric Pub., Inc. pp. 309–321. ISBN 1-58562-105-6.

- Agrawal A, Timothy J, Pandit L, Manju M (2006). "Post-traumatic epilepsy: An overview". Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 108 (5): 433–439. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.09.001. PMID 16225987. S2CID 2650670.

- Iudice A, Murri L (2000). "Pharmacological prophylaxis of post-traumatic epilepsy". Drugs. 59 (5): 1091–9. doi:10.2165/00003495-200059050-00005. PMID 10852641. S2CID 28616181.

- Teasell R, Bayona N, Lippert C, Villamere J, Hellings C (2007). "Post-traumatic seizure disorder following acquired brain injury". Brain Injury. 21 (2): 201–214. doi:10.1080/02699050701201854. PMID 17364531. S2CID 43871394.

- Frey LC (2003). "Epidemiology of posttraumatic epilepsy: A critical review". Epilepsia. 44 (Supplement 10): 11–17. doi:10.1046/j.1528-1157.44.s10.4.x. PMID 14511389. S2CID 34749005.

- Swash M (1998). Outcomes in neurological and neurosurgical disorders. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 172–173. ISBN 0-521-44327-X.

- Chang BS, Lowenstein DH (2003). "Practice parameter: Antiepileptic drug prophylaxis in severe traumatic brain injury: Report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 60 (1): 10–16. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000031432.05543.14. PMID 12525711.

- Garga N, Lowenstein DH (2006). "Posttraumatic epilepsy: a major problem in desperate need of major advances". Epilepsy Curr. 6 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1111/j.1535-7511.2005.00083.x. PMC 1363374. PMID 16477313.

- Cuccurullo S (2004). Physical medicine and rehabilitation board review. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 68–71. ISBN 1-888799-45-5. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- Benardo LS (2003). "Prevention of epilepsy after head trauma: Do we need new drugs or a new approach?". Epilepsia. 44 (Supplement 10): 27–33. doi:10.1046/j.1528-1157.44.s10.2.x. PMID 14511392. S2CID 35133349.

- Gupta A, Wyllie E, Lachhwani DK (2006). The Treatment of Epilepsy: Principles & Practice. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 521–524. ISBN 0-7817-4995-6.

- Young B (1992). "Post-traumatic epilepsy". In Barrow DL (ed.). Complications and Sequelae of Head Injury. Park Ridge, Ill: American Association of Neurological Surgeons. pp. 127–132. ISBN 1-879284-00-6.

- Herman ST (2002). "Epilepsy after brain insult: Targeting epileptogenesis". Neurology. 59 (9 Suppl 5): S21–S26. doi:10.1212/wnl.59.9_suppl_5.s21. PMID 12428028. S2CID 6978609.

- Menkes JH, Sarnat HB, Maria BL (2005). Child Neurology. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 683. ISBN 0-7817-5104-7. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- Kushner D (1998). "Mild traumatic brain injury: Toward understanding manifestations and treatment". Archives of Internal Medicine. 158 (15): 1617–1624. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.15.1617. PMID 9701095.

- Ropper AH, Gorson KC (2007). "Clinical practice. Concussion". New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (2): 166–172. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp064645. PMID 17215534.

- Posner E, Lorenzo N (October 11, 2006). "Posttraumatic epilepsy". Emedicine.com. Retrieved on 2008-02-19.

- Andrews BT (2003). Intensive Care in Neurosurgery. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers. p. 192. ISBN 1-58890-125-4. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- Beghi E (2003). "Overview of studies to prevent posttraumatic epilepsy". Epilepsia. 44 (Supplement 10): 21–26. doi:10.1046/j.1528-1157.44.s10.1.x. PMID 14511391. S2CID 25635858.

- Oliveros-Juste A, Bertol V, Oliveros-Cid A (2002). "Preventive prophylactic treatment in posttraumatic epilepsy". Revista de Neurología (in Spanish). 34 (5): 448–459. doi:10.33588/rn.3405.2001439. PMID 12040514.

- Chadwick D (2005). "Adult onset epilepsies". E-epilepsy - Library of articles, National Society for Epilepsy.

- Asikainen I, Kaste M, Sarna S (1999). "Early and late posttraumatic seizures in traumatic brain injury rehabilitation patients: Brain injury factors causing late seizures and influence of seizures on long-term outcome". Epilepsia. 40 (5): 584–589. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb05560.x. PMID 10386527. S2CID 20233355.

- D'Ambrosio R, Perucca E (2004). "Epilepsy after head injury". Current Opinion in Neurology. 17 (6): 731–735. doi:10.1097/00019052-200412000-00014. PMC 2672045. PMID 15542983.

- Firlik KS, Spencer DD (2004). "Surgery of post-traumatic epilepsy". In Dodson WE, Avanzini G, Shorvon SD, Fish DR, Perucca E (eds.). The Treatment of Epilepsy. Oxford: Blackwell Science. p. 775. ISBN 0-632-06046-8. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- Pitkänen A, McIntosh TK (2006). "Animal models of post-traumatic epilepsy". Journal of Neurotrauma. 23 (2): 241–261. doi:10.1089/neu.2006.23.241. PMID 16503807.