Retinal detachment

Retinal detachment is a disorder of the eye in which the retina peels away from its underlying layer of support tissue. Initial detachment may be localized, but without rapid treatment the entire retina may detach, leading to vision loss and blindness. It is a surgical emergency.[1]

| Retinal detachment | |

|---|---|

| |

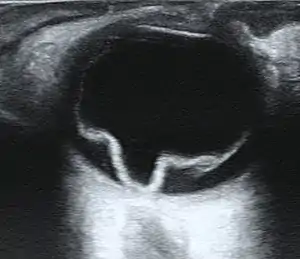

| Ultrasound of a retinal detachment in a patient presenting with complete vision loss and light perception only. | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

The retina is a thin layer of light-sensitive tissue on the back wall of the eye. The optical system of the eye focuses light on the retina much like light is focused on the film in a camera. The retina translates that focused image into neural impulses and sends them to the brain via the optic nerve. Occasionally, posterior vitreous detachment, injury or trauma to the eye or head may cause a small tear in the retina. The tear allows vitreous fluid to seep through it under the retina, and peel it away like a bubble in wallpaper.

Diagnosis

Symptoms

As the retina is responsible for vision, persons experiencing a retinal detachment have vision loss. This can be painful or painless.

Imaging

Ultrasound, MRI, and CT scan are commonly used to diagnose retinal detachment.

Types

- Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment – A rhegmatogenous retinal detachment occurs due to a hole or tear (both of which are referred to as retinal breaks) in the retina that allows fluid to pass from the vitreous space into the subretinal space between the sensory retina and the retinal pigment epithelium.

- Exudative, serous, or secondary retinal detachment – An exudative retinal detachment occurs due to inflammation, injury or vascular abnormalities that results in fluid accumulating underneath the retina without the presence of a hole, tear, or break.

- Tractional retinal detachment – A tractional retinal detachment occurs when fibrovascular tissue, caused by an injury, inflammation or neovascularization, pulls the sensory retina from the retinal pigment epithelium.

A small number of retinal detachments result from trauma, including blunt blows to the orbit, penetrating trauma, and concussions to the head. A retrospective Indian study of more than 500 cases of rhegmatogenous detachments found that 11% were due to trauma, and that gradual onset was the norm, with over 50% presenting more than one month after the inciting injury.[2]

Prevalence of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment

The risk of retinal detachment in otherwise normal eyes is around 5 in 100,000 per year.[3] Detachment is more frequent in the middle-aged or elderly population with rates of around 20 in 100,000 per year.[4] The lifetime risk in normal eyes is about 1 in 300.[5]

- Retinal detachment is more common in those with severe myopia (above 5–6 diopters), as their eyes are longer, their retina is thinner, and they more frequently have lattice degeneration. The lifetime risk increases to 1 in 20.[6] Myopia is associated with 67% of retinal detachment cases. Patients with a detachment related to myopia tend to be younger than non-myopic detachment patients.

- Retinal detachment can occur more frequently after surgery for cataracts. The estimated of risk of retinal detachment after cataract surgery is 5 to 16 per 1000 cataract operations.[7] The risk may be much higher in those who are highly myopic, with a frequency of 7% reported in one study.[8] Young age at cataract removal further increased risk in this study. Long term risk of retinal detachment after extracapsular and phacoemulsification cataract surgery at 2, 5, and 10 years was estimated in one study to be 0.36%, 0.77%, and 1.29%, respectively.[9]

- Tractional retinal detachments can also occur in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy[10] or those with proliferative retinopathy of sickle cell disease.[11] In proliferative retinopathy, abnormal blood vessels (neovascularization) grow within the retina and extend into the vitreous. In advanced disease, the vessels can pull the retina away from the back wall of the eye causing a traction retinal detachment.

Although retinal detachment usually occurs in one eye, there is a 15% chance of developing it in the other eye, and this risk increases to 25–30% in patients who have had cataracts extracted from both eyes.[6]

Symptoms of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment

A retinal detachment is commonly but not always preceded by a posterior vitreous detachment which gives rise to these symptoms:

- flashes of light (photopsia) – very brief in the extreme peripheral (outside of center) part of vision

- a sudden dramatic increase in the number of floaters

Sometimes a detachment may be due to atrophic retinal holes in which case it may not be preceded by photopsia or floaters.

Although most posterior vitreous detachments do not progress to retinal detachments, those that do produce the following symptoms:

- a dense shadow that starts in the peripheral vision and slowly progresses towards the central vision

- the impression that a veil or curtain was drawn over the field of vision

- straight lines (scale, edge of the wall, road, etc.) that suddenly appear curved (positive Amsler grid test)

- central visual loss

Treatment of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment

General Principles

- Find all the retinal breaks

- Seal all the retinal breaks

- Relieve present (and future) vitreoretinal traction

There are several methods of treating a detached retina which all depend on finding and closing the breaks which have formed in the retina.

- Cryopexy and Laser Photocoagulation

- Cryotherapy (freezing) or laser photocoagulation are occasionally used alone to wall off a small area of retinal detachment so that the detachment does not spread.

- Scleral buckle surgery

- Scleral buckle surgery is an established treatment in which the eye surgeon attaches one or more silicone bands (bands, tyres) to the sclera (the white outer coat of the eyeball). The bands push the wall of the eye inward against the retinal hole, closing the break or reducing fluid flow through it and reducing the effect of vitreous traction thereby allowing the retina to re-attach. Cryotherapy (freezing) is applied around retinal breaks prior to placing the buckle. Often subretinal fluid is drained as part of the buckling procedure. The buckle remains in situ indefinitely unless a buckle related complication such as exposure or infection develops. The most common side effect of a scleral operation is myopic shift. That is, the operated eye will be more short sighted after the operation due to the buckle causing the axial length to increase. A radial scleral buckle is occasionally indicated to U-shaped tears or fishmouthing tears. Circumferential scleral buckling is indicated when there are multiple breaks. Encircling buckles are indicated to breaks involving more than 2 quadrant of retinal area, lattice degeneration located in more than 2 quadrants, undetectable breaks, and where there is proliferative vitreous retinopathy.

- Pneumatic retinopexy

- This operation is generally performed in the doctor's office under local anesthesia. It is another method of repairing a retinal detachment in which a gas bubble (SF6 or C3F8 gas) is injected into the eye after which laser or freezing treatment is applied to the retinal hole. The patient's head is then positioned so that the bubble rests against the retinal hole. Patients may have to keep their heads tilted for several days to keep the gas bubble in contact with the retinal hole. The surface tension of the air/water interface seals the hole in the retina, and allows the retinal pigment epithelium to pump the subretinal space dry and suck the retina back into place. This strict positioning requirement makes the treatment of the retinal holes and detachments that occurs in the lower part of the eyeball impractical. This procedure is always combined with cryopexy or laser photocoagulation. The one operation reattachment rate may be slightly lower with pneumatic retinopexy but in spite of this, the final visual acuity may be better.

- Vitrectomy

- Vitrectomy is an increasingly used treatment for retinal detachment. It involves the removal of the vitreous gel and is usually combined with filling the eye with either a gas bubble (SF6 or C3F8 gas) or silicone oil. Advantages of using gas in this operation is that there is no myopic shift after the operation and gas is absorbed within a few weeks. Silicone oil is almost always removed after a period of 2–8 months depending on surgeon's preference. Silicone oil is more commonly used in cases associated with proliferative vitreo-retinopathy (PVR). Silicone oil may be light or heavy depending on the position of the breaks requiring tamponade. A disadvantage is that a vitrectomy always leads to more rapid progression of a cataract in the operated eye. In many places vitrectomy is the most commonly performed operation for the treatment of retinal detachment.

Results of Surgery

85 percent of cases will be successfully treated with one operation with the remaining 15 percent requiring 2 or more operations. After treatment patients gradually regain their vision over a period of a few weeks, although the visual acuity may not be as good as it was prior to the detachment, particularly if the macula was involved in the area of the detachment. However, if left untreated, total blindness will occur in a matter of weeks.

Prevention

Retinal detachment can sometimes be prevented. The most effective means is by educating people to seek ophthalmic medical attention if they have symptoms suggestive of a posterior vitreous detachment.[12] Early examination allows detection of retinal tears which can be treated with laser or cryotherapy. This reduces the risk of retinal detachment in those who have tears from around 1:3 to 1:20.

There are some known risk factors for retinal detachment. There are also many activities which at one time or another have been forbidden to those at risk of retinal detachment, with varying degrees of evidence supporting the restrictions.

Cataract surgery is a major cause, and can result in detachment even a long time after the operation. The risk is increased if there are complications during cataract surgery, but remains even in apparently uncomplicated surgery. The increasing rates of cataract surgery, and decreasing age at cataract surgery, inevitably lead to an increased incidence of retinal detachment.

Trauma is a less frequent cause. Activities which can cause direct trauma to the eye (boxing, kickboxing, karate, etc.) may cause a particular type of retinal tear called a retinal dialysis. This type of tear can be detected and treated before it develops into a retinal detachment. For this reason governing bodies in some of these sports require regular eye examination.

Individuals prone to retinal detachment due to a high level of myopia are encouraged to avoid activities where there is a risk of shock to the head or eyes, although without direct trauma to the eye the evidence base for this may be unconvincing.[6] Some doctors recommend avoiding activities that suddenly accelerate or decelerate the eye, including bungee jumping and skydiving but with little supporting evidence. Retinal detachment does not occur as a result of eye strain, bending, or heavy lifting.[13]

See also

References

- "Retinal detachment". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. National Institutes of Health. 2005. Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- Shukla Manoj, Ahuja OP, Jamal Nasir (1986). "Epidemiological study of nontraumatic phakic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment". Indian J Ophthalmol. 34: 29–32.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ivanisević M, Bojić L, Eterović D (2000). "Epidemiological study of nontraumatic phakic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment". Ophthalmic Res. 32 (5): 237–9. doi:10.1159/000055619. PMID 10971186. S2CID 43277835.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Li X (2003). "Incidence and epidemiological characteristics of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in Beijing, China". Ophthalmology. 110 (12): 2413–7. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00867-4. PMID 14644727.

- "Evaluation and Management of Suspected Retinal Detachment - April 1, 2004 - American Family Physician". Archived from the original on 2008-07-24. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- "eMedicine – Retinal Detachment: Article by Gregory Luke Larkin, MD, MSPH, MSEng, FACEP". Archived from the original on 2008-01-14. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- Ramos M, Kruger EF, Lashkari K (2002). "Biostatistical analysis of pseudophakic and aphakic retinal detachments". Seminars in Ophthalmology. 17 (3–4): 206–13. doi:10.1076/soph.17.3.206.14784. PMID 12759852. S2CID 10060144.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hyams SW, Bialik M, Neumann E (1975). "Myopia-aphakia. I. Prevalence of retinal detachment". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 59 (9): 480–2. doi:10.1136/bjo.59.9.480. PMC 1042658. PMID 1203233.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rowe, Jonathan A.; Erie, Jay C.; Baratz, Keith H. (1999). "Retinal detachment in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976 through 1995". Ophthalmology. 106 (1): 154–159. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90018-0. PMID 9917797.

- "Diabetic Retinopathy: Retinal Disorders: Merck Manual Home Edition". Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- "IU Opt Online CE: Retinal Vascular Disease: Sickle Cell Retinopathy". Archived from the original on 2003-01-11. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- Byer NE (1994). "Natural history of posterior vitreous detachment with early management as the premier line of defense against retinal detachment". Ophthalmology. 101 (9): 1503–13, discussion 1513–4. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31141-9. PMID 8090453.

- "Understanding retinal detachment". Retrieved 2007-06-04.

External links

- Retinal Detachment Resource Guide from the National Eye Institute (NEI)

- Overview of retinal detachment from eMedicine

- Retinal detachment information from WebMD