Sensory-motor coupling

Sensory-motor coupling is the coupling or integration of the sensory system and motor system. Sensorimotor integration is not a static process. For a given stimulus, there is no one single motor command. "Neural responses at almost every stage of a sensorimotor pathway are modified at short and long timescales by biophysical and synaptic processes, recurrent and feedback connections, and learning, as well as many other internal and external variables".[1]

Overview

The integration of the sensory and motor systems allows an animal to take sensory information and use it to make useful motor actions. Additionally, outputs from the motor system can be used to modify the sensory system's response to future stimuli.[1][2] To be useful it is necessary that sensory-motor integration be a flexible process because the properties of the world and ourselves change over time. Flexible sensorimotor integration would allow an animal the ability to correct for errors and be useful in multiple situations.[1][3] To produce the desired flexibility it's probable that nervous systems employ the use of internal models and efference copies.[2][3][4]

Transform sensory coordinates to motor coordinates

Prior to movement, an animal's current sensory state is used to generate a motor command. To generate a motor command, first, the current sensory state is compared to the desired or target state. Then, the nervous system transforms the sensory coordinates into the motor system's coordinates, and the motor system generates the necessary commands to move the muscles so that the target state is reached.[2]

Efference copy

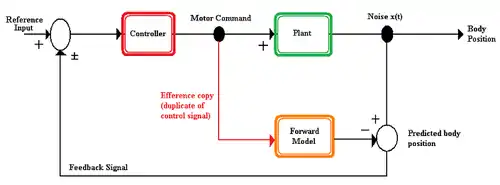

An important aspect of sensorimotor integration is the efference copy. The efference copy is a copy of a motor command that is used in internal models to predict what the new sensory state will be after the motor command has been completed. The efference copy can be used by the nervous system to distinguish self-generated environmental changes, compare an expected response to what actually occurs in the environment, and to increase the rate at which a command can be issued by predicting an organism's state prior to receiving sensory input.[2][5]

Internal model

An internal model is a theoretical model used by a nervous system to predict the environmental changes that result from a motor action. The assumption is that the nervous system has an internal representation of how a motor apparatus, the part of the body that will be moved, behaves in an environment.[6][7] Internal models can be classified as either a forward model or an inverse model.

Forward model

A forward model is a model used by the nervous system to predict the new state of the motor apparatus and the sensory stimuli that result from a motion. The forward model takes the efference copy as an input and outputs the expected sensory changes.[4] Forward models offer several advantages to an organism.

Advantages:

- The estimated future state can be used to coordinate movement before sensory feedback is returned.[3][4]

- The output of a forward model can be used to differentiate between self-generated stimuli and non-self-generated stimuli.[4]

- The estimated sensory feedback can be used to alter an animal's perception related to self-generated motion.[3]

- The difference between the expected sensory state and sensory feedback can be used to correct errors in movement and the model.[3]

Examples

Gaze stabilization

During flight, it is important for a fly to maintain a level gaze; however, it is possible for a fly to rotate. The rotation is detected visually as a rotation of the environment termed optical flow. The input of the optical flow is then converted into a motor command to the fly's neck muscles so that the fly will maintain a level gaze. This reflex is diminished in a stationary fly compared to when it is flying or walking.[1]

Singing crickets

Male crickets sing by rubbing their forewings together. The sounds produced are loud enough to reduce the cricket's auditory system's response to other sounds. This desensitization is caused by the hyperpolarization of the Omega 1 neuron (ON1), an auditory interneuron, due to activation by auditory stimulation.[5] To reduce self-desensitization, the cricket's thoracic central pattern generator sends a corollary discharge, an efference copy that is used to inhibit an organism's response to self-generated stimuli, to the auditory system.[1][5] The corollary discharge is used to inhibit the auditory system's response to the cricket's own song and prevent desensitization. This inhibition allows the cricket to remain responsive to external sounds such as a competing male's song.[8]

Speech

Sensorimotor integration is involved in the development, production, and perception of speech.[9][10]

Speech development

Two key elements of speech development are babbling and audition. The linking of a motor action to a heard sound is thought to be learned. One reason for this is that deaf infants do not canonically babble. Another is that an infant's perception is known to be affected by his babbling. One model of speech development proposes that the sounds produced by babbling are compared to the sounds produced in the language used around the infant and that association of a motor command to a sound is learned.[10]

Speech production

Audition plays a critical role in the production and maintenance of speech. As an example, people who experience adult-onset deafness become less able to produce accurate speech. This decline is because they lack auditory feedback. Another example is acquisition of a new accent as a result of living in an area with a different accent.[9] These changes can be explained through the use of a forward model.

In this forward model, the motor cortex sends a motor command to the vocal tract and an efference copy to the internal model of the vocal tract. The internal model predicts what sounds will be produced. This prediction is used to check that the motor command will produce the goal sound so that corrections may be made. The internal model's estimate is also compared to the produced sound to generate an error estimate. The error estimate is used to correct the internal model. The updated internal model will then be used to generate future motor commands.[9]

Speech perception

Sensorimotor integration is not critical to the perception of speech; however, it does perform a modulatory function. This is supported by the fact that people who either have impaired speech production or lack the ability to speak are still capable of perceiving speech. Furthermore, experiments in which motor areas related to speech were stimulated altered but did not prevent the perception of speech.[9]

Patient R.W.

Patient R.W. was a man who suffered damage in his parietal and occipital lobes, areas of the brain related to processing visual information, due to a stroke. As a result of his stroke, he experienced vertigo when he tried to track a moving object with his eyes. The vertigo was caused by his brain interpreting the world as moving. In normal people, the world is not perceived as in moving when tracking an object despite the fact that the image of the world is moved across the retina as the eye moves. The reason for this is that the brain predicts the movement of the world across the retina as a consequence of moving the eyes. R.W., however, was unable to make this prediction.[3]

Disorders

Parkinson's

Patients with Parkinson's disease often show symptoms of bradykinesia and hypometria. These patients are more dependent on external cues rather than proprioception and kinesthesia when compared to other people.[11] In fact, studies using external vibrations to create proprioceptive errors in movement show that Parkinson's patients perform better than healthy people. Patients have also been shown to underestimate the movement of limb when it was moved by researchers.[11] Additionally, studies on somatosensory evoked potentials have evidenced that the motor problems are likely related to an inability to properly process the sensory information and not in the generation of the information.

Huntington's

Huntington's patients often have trouble with motor control. In both quinolinic models and patients, it has been shown that people with Huntington's have abnormal sensory input. Additionally, patients have been shown to have a decrease in the inhibition of the startle reflex. This decrease indicates a problem with proper sensorimotor integration. The " various problems in integrating sensory information explain why patients with HD are unable to control voluntary movements accurately."[11]

Dystonia

Dystonia is another motor disorder that presents sensorimotor integration abnormalities. There are multiple pieces of evidence that indicate focal dystonia is related to improper linking or processing of afferent sensory information in the motor regions of the brain.[11] For example, dystonia can be partially relieved through the use of a sensory trick. A sensory trick is the application of a stimulus to an area near to the location affected by dystonia that provides relief. Positron emission tomography studies have shown that the activity in both the supplementary motor area and primary motor cortex are reduced by the sensory trick. More research is necessary on sensorimotor integration dysfunction as it relates to non-focal dystonia.[11]

Restless leg syndrome

Restless leg syndrome (RLS) is a sensorimotor disorder. People with RLS are plagued with feelings of discomfort and the urge to move in the legs. These symptoms occur most frequently at rest. Research has shown that the motor cortex has increased excitability in RLS patients compared to healthy people. Somatosensory evoked potentials from the stimulation of both posterior nerve and median nerve are normal.[12] The normal SEPs indicate that the RLS is related to abnormal sensorimotor integration. In 2010, Vincenzo Rizzo et al. provided evidence that RLS sufferers have lower than normal short latency afferent inhibition (SAI), inhibition of the motor cortex by afferent sensory signals. The decrease of SAI indicates the presence of abnormal sensory-motor integration in RLS patients.[12]

See also

- Motor control

- Motor learning

- Motor goal

- Motor coordination

- Multisensory integration

- Sensory processing

References

- Huston, Stephen J; Jayaraman, Vivek (2011). "Studying sensorimotor integration in insects". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 21 (4): 527–534. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2011.05.030. ISSN 0959-4388. PMID 21705212. S2CID 18086965.

- Flanders M (February 2011). "What is the biological basis of sensorimotor integration?". Biol Cybern. 104 (1–2): 1–8. doi:10.1007/s00422-011-0419-9. PMC 3154729. PMID 21287354.

- Shadmehr, Reza; Smith, Maurice A.; Krakauer, John W. (2010). "Error Correction, Sensory Prediction, and Adaptation in Motor Control" (PDF). Annual Review of Neuroscience. 33 (1): 89–108. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153135. ISSN 0147-006X. PMID 20367317.

- Wolpert, D.; Ghahramani, Z; Jordan, M. (1995). "An internal model for sensorimotor integration" (PDF). Science. 269 (5232): 1880–1882. Bibcode:1995Sci...269.1880W. doi:10.1126/science.7569931. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 7569931.

- Poulet JF, Hedwig B (March 2003). "A corollary discharge mechanism modulates central auditory processing in singing crickets". J. Neurophysiol. 89 (3): 1528–40. doi:10.1152/jn.0846.2002. PMID 12626626.

- Kawato M (December 1999). "Internal models for motor control and trajectory planning" (PDF). Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 9 (6): 718–27. doi:10.1016/S0959-4388(99)00028-8. PMID 10607637. S2CID 878792.

- Tin C, Poon CS (September 2005). "Internal models in sensorimotor integration: perspectives from adaptive control theory". Journal of Neural Engineering. 2 (3): S147–63. doi:10.1088/1741-2560/2/3/S01. PMC 2263077. PMID 16135881.

- Webb B (May 2004). "Neural mechanisms for prediction: do insects have forward models?". Trends Neurosci. 27 (5): 278–82. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2004.03.004. PMID 15111010. S2CID 2601664.

- Hickok G, Houde J, Rong F (February 2011). "Sensorimotor integration in speech processing: computational basis and neural organization". Neuron. 69 (3): 407–22. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.019. PMC 3057382. PMID 21315253.

- Westermann G, Reck Miranda E (May 2004). "A new model of sensorimotor coupling in the development of speech". Brain Lang. 89 (2): 393–400. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.3.6041. doi:10.1016/S0093-934X(03)00345-6. PMID 15068923. S2CID 3138711.

- Abbruzzese G, Berardelli A (March 2003). "Sensorimotor integration in movement disorders". Mov. Disord. 18 (3): 231–40. doi:10.1002/mds.10327. PMID 12621626. S2CID 23078987.

- Rizzo V, Aricò I, Liotta G, et al. (December 2010). "Impairment of sensory-motor integration in patients affected by RLS". J. Neurol. 257 (12): 1979–85. doi:10.1007/s00415-010-5644-y. PMID 20635185. S2CID 13494398.