Skin biopsy

Skin biopsy is a biopsy technique in which a skin lesion is removed to be sent to a pathologist to render a microscopic diagnosis. It is usually done under local anesthetic in a physician's office, and results are often available in 4 to 10 days. It is commonly performed by dermatologists. Skin biopsies are also done by family physicians, internists, surgeons, and other specialties. However, performed incorrectly, and without appropriate clinical information, a pathologist's interpretation of a skin biopsy can be severely limited, and therefore doctors and patients may forgo traditional biopsy techniques and instead choose Mohs surgery. There are four main types of skin biopsies: shave biopsy, punch biopsy, excisional biopsy, and incisional biopsy. The choice of the different skin biopsies is dependent on the suspected diagnosis of the skin lesion. Like most biopsies, patient consent and anesthesia (usually lidocaine injected into the skin) are prerequisites.

| Skin biopsy | |

|---|---|

Punch biopsy | |

| ICD-9-CM | 86.11 |

Types

Shave biopsy

A shave biopsy is done with either a small scalpel blade or a curved razor blade. The technique is very much user skill dependent, as some surgeons can remove a small fragment of skin with minimal blemish using any one of the above tools, while others have great difficulty securing the devices. Ideally, the razor will shave only a small fragment of protruding tumor and leave the skin relatively flat after the procedure. Hemostasis is obtained using light electrocautery, Monsel's solution, or aluminum chloride. This is the ideal method of diagnosis for basal cell cancer. It can be used to diagnose squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma-in-situ, however, the doctor's understanding of the growth of these last two cancers should be considered before one uses the shave method. The punch or incisional method is better for the latter two cancers as a false negative is less likely to occur (i.e. calling a squamous cell cancer an actinic keratosis or keratinous debris). Hemostasis for the shave technique can be difficult if one relies on electrocautery alone. A small "shave" biopsy often ends up being a large burn defect when the surgeon tries to control the bleeding with electrocautery alone. Pressure dressing or chemical astringent can help in hemostasis in patients taking anticoagulants.

Punch biopsy

A punch biopsy is done with a circular blade ranging in size from 1 mm to 8 mm. The blade, which is attached to a pencil-like handle, is rotated down through the epidermis and dermis, and into the subcutaneous fat, producing a cylindrical core of tissue.[1] An incision made with a punch biopsy is easily closed with one or two sutures. Some punch biopsies are shaped like an ellipse, although one can accomplish the same desired shape with a standard scalpel. The 1 mm and 1.5 mm punch are ideal for locations where cosmetic appearance is difficult to accomplish with the shave method. Minimal bleeding is noted with the 1 mm punch, and often the wound is left to heal without stitching for the smaller punch biopsies. The disadvantage of the 1 mm punch is that the tissue obtained is almost impossible to see at times due to small size, and the 1.5 mm biopsy is preferred in most cases. The common punch size used to diagnose most inflammatory skin conditions is the 3.5 or 4 mm punch.[2]

Incisional biopsy

In an incisional biopsy a cut is made through the entire dermis down to the subcutaneous fat. A punch biopsy is essentially an incisional biopsy, except it is round rather than elliptical as in most incisional biopsies done with a scalpel. Incisional biopsies can include the whole lesion (excisional), part of a lesion, or part of the affected skin plus part of the normal skin (to show the interface between normal and abnormal skin). Incisional biopsy often yield better diagnosis for deep pannicular skin diseases and more subcutaneous tissue can be obtained than a punch biopsy. Long and thin deep incisional biopsy are excellent on the lower extremities as they allow a large amount of tissue to be harvested with minimal tension on the surgical wound. Advantage of the incisional biopsy over the punch method is that hemostasis can be done more easily due to better visualization. Dog ear defects are rarely seen in incisional biopsies with length at least twice as long as the width.

Excisional biopsy

An excisional biopsy is essentially the same as incisional biopsy, except the entire lesion or tumor is included. This is the ideal method of diagnosis of small melanomas (when performed as an excision). Ideally, an entire melanoma should be submitted for diagnosis if it can be done safely and cosmetically. This excisional biopsy is often done with a narrow surgical margin to make sure the deepest thickness of the melanoma is given before prognosis is decided. However, as many melanoma-in-situs are large and on the face, a physician will often chose to do multiple small punch biopsies before committing to a large excision for diagnostic purpose alone. Many prefer the small punch method for initial diagnostic value before resorting to the excisional biopsy. An initial small punch biopsy of a melanoma might say "severe cellular atypia, recommend wider excision". At this point, the clinician can be confident that an excisional biopsy can be performed without risking committing a "false positive" clinical diagnosis.

| Lesion size | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| <4 mm | 4 – 8 mm | 9 – 15 mm | |

| Benign appearance |

|

|

|

| Suspected malignancy |  |

|

|

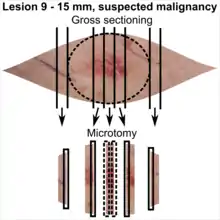

In table above, each top image shows recommended lines for cutting out slices to be submitted for further processing. Bottom image shows which side of the slice that should be put to microtomy. Dashed lines here mean that either side could be used. The entire specimen may be sliced and submitted if the risk of malignancy is high.[3] Otherwise the rest may be saved in fixation in case microscopy indicates further sampling.

Curettage biopsy

A curettage biopsy can be done on the surface of tumors or on small epidermal lesions with minimal to no topical anesthetic using a round curette blade. Diagnosis of basal cell cancer can be made with some limitation, as morphology of the tumor is often disrupted. The pathologist must be informed about the type of anesthetic used, as topical anesthetic can cause artifact in the epidermal cells. Liquid nitrogen or cryotherapy can be used as a topical anesthetic, however, freezing artifacts can severely hamper the diagnosis of malignant skin cancers.

Fine needle aspirate

Needle aspiration biopsy is done with the rapid stabbing motion of the hand guiding a needle tipped syringe and the rapid sucking motion applied to the syringe. It is a method used to diagnose tumor deep in the skin or lymph nodes under the skin. The cellular aspirate is mounted on a glass slide and immediate diagnosis can be made with proper staining or submitted to a laboratory for final diagnosis. A fine needle aspirate can be done with simply a small bore needle and a small syringe (1 cc) that can generate rapid changes in suction pressure. Fine needle aspirate can be used to distinguish a cystic lesion from a lipoma. Both the surgeon and the pathologist must be familiar with the method of procuring, fixing, and reading of the slide. Many centers have dedicated teams used in the harvest of fine needle aspirate.

Saucerization biopsy

A saucerization biopsy is also known as "scoop", "scallop", or "shave" excisional biopsy,[4] or "shave" excision. A trend has occurred in dermatology over the last 10 years with the advocacy of a deep shave excision of a pigmented lesion.[5][6][7] An author published the result of this method and advocated it as better than standard excision and less time-consuming. The added economic benefit is that many surgeons bill the procedure as an excision, rather than a shave biopsy. This saves the added time for hemostasis, instruments, and suture cost. The great disadvantage, seen years later, is the numerous scallop scars, and the appearance of a lesion called a "recurrent melanocytic nevus"; many "shave" excisions do not penetrate the dermis or subcutaneous fat enough to include the entire melanocytic lesion, and residual melanocytes regrow into the scar. The combination of scarring, inflammation, blood vessels, and atypical pigmented streaks seen in these recurrent nevi may result in the dermatoscopic appearance of a melanoma.[8][9][10][11] When a second physician later examines the patient, he or she has no choice but to recommend re-excision of the scar. If one does not have access to the original pathology report, it is impossible to distinguish a recurring nevus from a severely dysplastic nevus or melanoma. As the procedure is widely practiced, it is not unusual to see a patient with dozens of scallop scars, with as many as 20% of them showing residual pigmentation. The second issue with the shave excision is fat herniation, iatrogenic anetoderma, and hypertrophic scarring. As the deep shave excision either completely removes the full thickness of the dermis or greatly diminishes the dermal thickness, subcutaneous fat can herniate outward or pucker the skin out in an unattractive way. In areas prone to friction, this can result in pain, itching, or hypertrophic scarring.

Pathology report

A pathology report is highly dependent on the quality of the biopsy that is submitted. It is not unusual to miss the diagnosis of a skin tumor or a skin biopsy due to a poorly performed or inappropriately performed skin biopsy. The clinical information provided to the pathologist will also affect the final diagnosis. An example would be a rapidly growing dome shaped tumor of the sun exposed skin. Despite doing a large wedge incision, a pathologist might call the biopsy keratin debris with characteristics of actinic keratosis. But provided with an accurate clinical information, he/she might consider the diagnosis of a well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma or keratoacanthoma. It is not infrequent for two, three or more biopsies to be performed by different doctors for the same skin condition, before the correct diagnosis is made on the final biopsy. The method, depth, and quality of clinical data will all affect the yield of a skin biopsy. For this reason, doctors specializing in skin diseases are invaluable in the diagnosis of skin cancers and difficult skin diseases. Specific stains (PAS, DIF, etc.), and certain type of sectioning (vertical and horizontal) are often requested by an astute physician to make sure that the pathologist will have all the necessary information to make a good histological diagnosis.

References

- Zuber, Thomas J. (2002). "Punch biopsy of the skin". American Family Physician. 65 (6): 1155–1158. PMID 11925094. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- Zuber, Thomas J. (2002-03-15). "Punch Biopsy of the Skin". American Family Physician. 65 (6): 1155–8, 1161–2, 1164. PMID 11925094.

- There are many variants for the processing of skin excisions. These examples use aspects from the following sources:

- "Handläggning av hudprover – provtagningsanvisningar, utskärningsprinciper och snittning (Handling of skin samples - sampling instructions, cutting principles and incision" (PDF). Swedish Society of Pathology.

- For number of slices and coverage of lesions, as well as including sections from each edge in case of diffuse border. - "Dermatopathology Grossing Guidelines" (PDF). University of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- For microtomy of the most central side at the lesion - Finley EM (2003). "The principles of mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous neoplasia". Ochsner J. 5 (2): 22–33. PMC 3399331. PMID 22826680.

- With a "standard histologic examination" that, in addition to the lesion, only includes one section from each side along the longest diameter of the specimen.

- It also shows an example of circular coverage, with equal coverage distance in all four directions.

- The entire specimen may be submitted if the risk of malignancy is high.

- "Handläggning av hudprover – provtagningsanvisningar, utskärningsprinciper och snittning (Handling of skin samples - sampling instructions, cutting principles and incision" (PDF). Swedish Society of Pathology.

- Ho, J.; Brodell, R.; Helms, S. (2005). "Saucerization biopsy of pigmented lesions". Clinics in Dermatology. 23 (6): 631–635. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.06.004. PMID 16325072.

- Mendese, Gary W. (1 June 2007). "The Diagnostic and Therapeutic Utility of the Scoop-Shave for Pigmented Lesions of the Skin". Senior Scholars Program. University of Massachusetts Medical School. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- Buka, Robert L.; Ness, Rachel C. (2008). "Surgical Pearl: The Pendulum or "Scoop" Biopsy". Clinical Medicine & Research. Marshfield Clinic. 6 (2): 86–87. doi:10.3121/cmr.2008.804. PMC 2572555. PMID 18801951. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- "Plastic Surgery | Manhattan Dermatology". Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2014-01-31.

- Soyer, Hans Peter; Argenziano, Giuseppe; Hofmann-Wellenhof, Rainer; Johr, Robert H. (2007). Color Atlas of Melanocytic Lesions of the Skin, Recurrent Nevus. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-35106-1_23. ISBN 978-3-540-35105-4.

- "Recurrent Nevus". rjreed.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- Ehrsam, Eric (21 November 2007). "Dermoscopy, Recurrent Nevus". Dr Eric Ehrsam Dermatologist. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- "Congenital Blastoid Nevus". rjreed.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2013.