Sluggish cognitive tempo

Sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) is a syndrome related to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) but distinct from it. Typical symptoms include prominent dreaminess, mental fogginess, hypoactivity, sluggishness, staring frequently, inconsistent alertness and a slow working speed.

| Sluggish cognitive tempo | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychology |

SCT has been a subject of controversy for decades and debate about its nature still continues.[1] But it is clear now that this set of symptoms is important because it independently has a negative impact on functioning (such as a diminished quality of life,[2] increased stress and suicidal behaviour,[3] as well as lower educational attainment and socioeconomic status[4]). The SCT symptoms are clinically relevant as they seem linked to a poor treatment response to methylphenidate.[5]

Originally, SCT was thought to occur only in about one in three persons with the inattentive subtype of ADHD,[6] and to be incompatible with hyperactivity. But new studies found it also in some people with the other two ADHD subtypes – and in individuals without ADHD as well. Therefore, some psychologists and psychiatrists view it as a separate mental disorder. Others dismiss it altogether or believe it is a distinct symptom group within ADHD (like Hyperactivity, Impulsivity or Inattention). It even may be useful as an overarching concept that cuts across different psychiatric disorders (much like emotional dysregulation, for example).[7]

If SCT and ADHD occur together, the problems add up: Those with both (ADHD + SCT) had higher levels of impairment and inattention than adults with ADHD only,[8] and were more likely to be unmarried, out of work or on disability.[9] But SCT alone is also present in the population and can be quite impairing in educational and occupational settings, even if it is not as pervasively impairing as ADHD. Some have encouraged the use of a term such as concentration deficit disorder (CDD) or cognitive disengagement syndrome (CDS) instead of SCT because it may be more appropriate and less derogatory.[9][10]

Signs and symptoms

ADHD is the only disorder of attention currently defined by the DSM-5 or ICD-10. Formal diagnosis is made by a qualified professional. It includes demonstrating six or more of the following symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity-impulsivity (or both).[11][12]

| ADHD symptoms (DSM-5) | |

|---|---|

| Inattention | Hyperactivity-Impulsivity |

|

|

The symptoms must also

- be age-inappropriate,

- start before age 12,

- occur often and be present in at least two settings,

- clearly interfere with social, school, or work functioning,

- and not be better explained by another mental disorder.

Based on the above symptoms, three types of ADHD are defined:

- a predominantly inattentive presentation (ADHD-I)

- a predominantly hyperactive-impulsive presentation (ADHD-HI)

- a combined presentation (ADHD-C)

The predominantly inattentive presentation (ADHD-I) in DSM 5 is restricted to the official inattention symptoms (see table above) and only to those. They capture problems with persistence, distractibility and disorganization. But it fails to include these other, qualitatively different symptoms:[13][14][4]

| SCT symptoms (preliminary research criteria) | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

As a comparison of both tables shows, there is no overlap between the official ADHD inattention symptoms and the SCT symptoms. That means that both symptom clusters do not refer to the same attention problems. They may exist in parallel within the same person but do also occur alone. However, one problem is still that some individuals who actually have SCT are currently misdiagnosed with the inattentive presentation.[4]

Social behaviour

In many ways, those who have an SCT profile have some of the opposite symptoms of those with predominantly hyperactive-impulsive or combined type ADHD: instead of being hyperactive, extroverted, obtrusive, excessively energetic and risk takers, those with SCT are drifting, absent-minded, listless, introspective and daydreamy. They feel like they are "in the fog" and seem "out of it".[15]

The comorbid psychiatric problems often associated with SCT are more often of the internalizing types, such as anxiety, unhappiness or depression.[6] Most consistent across studies was a pattern of reticence and social withdrawal in interactions with peers. Their typically shy nature and slow response time has often been misinterpreted as aloofness or disinterest by others. In social group interactions, those with SCT may be ignored. People with classic ADHD are more likely to be rejected in these situations, because of their social intrusiveness or aggressive behavior. Compared to children with SCT, they are also much more likely to show antisocial behaviours like substance abuse, oppositional-defiant disorder or conduct disorder (frequent lying, stealing, fighting etc.).[9] Fittingly, in terms of personality, ADHD seems to be associated with sensitivity to reward and fun seeking while SCT may be associated with punishment sensitivity.[16][9]

Attention deficits

Individuals with SCT symptoms may show a qualitatively different kind of attention deficit that is more typical of a true information processing problem; such as poor focusing of attention on details or the capacity to distinguish important from unimportant information rapidly. In contrast, people with ADHD have more difficulties with persistence of attention and action toward goals coupled with impaired resistance to responding to distractions. Unlike SCT, those with classic ADHD have problems with inhibition but have no difficulty selecting and filtering sensory input.[17][9]

Some think that SCT and ADHD produce different kinds of inattention: While those with ADHD can engage their attention but fail to sustain it over time, people with SCT seem to have difficulty with engaging their attention to a specific task.[18][19] Accordingly, the ability to orient attention has been found to be abnormal in SCT.[20]

Both disorders interfere significantly with academic performance but may do so by different means. SCT may be more problematic with the accuracy of the work a child does in school and lead to making more errors. Conversely, ADHD may more adversely affect productivity which represents the amount of work done in a particular time interval. Children with SCT seem to have more difficulty with consistently remembering things that were previously learned and make more mistakes on memory retrieval tests than do children with ADHD. They have been found to perform much worse on psychological tests involving perceptual-motor speed or hand-eye coordination and speed. They also have a more disorganized thought process, a greater degree of sloppiness, and lose things more easily. The risk for additional learning disabilities seems equal in both ADHD and SCT (23–50%) but math disorders may be more frequent in the SCT-group.[15]

A key behavioral characteristic of those with SCT symptoms is that they are more likely to appear to be lacking motivation and may even have an unusually higher frequency of daytime sleepiness.[21] They seem to lack energy to deal with mundane tasks and will consequently seek to concentrate on things that are mentally stimulating perhaps because of their underaroused state. Alternatively, SCT may involve a pathological form of excessive mind-wandering.[9]

Executive function

The executive system of the human brain provides for the cross-temporal organization of behavior towards goals and the future and coordinates actions and strategies for everyday goal-directed tasks. Essentially, this system permits humans to self-regulate their behavior so as to sustain action and problem solving toward goals specifically and the future more generally. Dysexecutive syndrome is defined as a "cluster of impairments generally associated with damage to the frontal lobes of the brain" which includes "difficulties with high-level tasks such as planning, organising, initiating, monitoring and adapting behaviour".[22] Such executive deficits pose serious problems for a person's ability to engage in self-regulation over time to attain their goals and anticipate and prepare for the future.

Adele Diamond postulated that the core cognitive deficit of those with ADHD-I is working memory, or, as she coined in her recent paper on the subject, "childhood-onset dysexecutive syndrome".[23] However, two more recent studies by Barkley found that while children and adults with SCT had some deficits in executive functions (EF) in everyday life activities, they were primarily of far less magnitude and largely centered around problems with self-organization and problem-solving. Even then, analyses showed that most of the difficulties with EF deficits were the result of overlapping ADHD symptoms that may co-exist with SCT rather than being attributable to SCT itself. More research on the link of SCT to EF deficits is clearly indicated—but, as of this time, SCT does not seem to be as strongly associated with EF deficits as is ADHD.[9]

Causes

Unlike ADHD, the general causes of SCT symptoms are almost unknown, though one recent study of twins suggested that the condition appears to be nearly as heritable or genetically influenced in nature as ADHD.[24] That is to say that the majority of differences among individuals in these traits in the population may be due mostly to variation in their genes. The heritability of SCT symptoms in that study was only slightly lower than that for ADHD symptoms with a somewhat greater share of trait variation being due to unique environmental events. For instance, in ADHD, the genetic contribution to individual differences in ADHD traits typically averages between 75 and 80% and may even be as high as 90%+ in some studies. That for SCT maybe 50–60%.

Little is known about the neurobiology of SCT. But the SCT symptoms seem to indicate that the posterior attention networks may be more involved here than the prefrontal cortex region of the brain and difficulties with working memory so prominent in ADHD. This hypothesis gained greater support following a 2015 neuroimaging study comparing ADHD inattentive symptoms and SCT symptoms in adolescents: It found that SCT was associated with a decreased activity in the left superior parietal lobule (SPL), whereas inattentive symptoms were associated with other differences in activation.[25] A 2018 study showed an association between SCT and specific parts of the frontal lobes, differing from classical ADHD neuroanatomy.[26]

A study showed a small link between thyroid functioning and SCT symptoms suggesting that thyroid dysfunction is not the cause of SCT. High rates of SCT were observed in children who had prenatal alcohol exposure and in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia, where they were associated with cognitive late effects.[27][28][29]

Diagnosis

SCT is currently not an official diagnosis in DSM-5 and no universally accepted set of symptoms exists yet. But there are rating scales that can be used to screen for SCT symptoms such as the Concentration Inventory (for children and adults) or the Barkley Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Scale-Children and Adolescents (BSCTS-CA).[30][14] The Comprehensive Behaviour Rating Scale for Children (CBRSC), an older scale, can also be used for SCT as this case study shows.[31] Additional requirements for a proposed SCT diagnosis (such as the number and duration of symptoms or the impact on functioning) are continuing to be investigated.

Although having no diagnostic code either, ICD-10 mentions the SCT group as a reason for why it did not replace the term "Hyperkinetic Disorder" with "ADHD".[32]

Other mental disorders may produce similar symptoms to SCT (e.g. excessive daydreaming or "staring blankly") and should not be confused with it. Examples might be conditions like depersonalization disorder, dysthymia, thyroid problems,[27] absence seizures, Bipolar II disorder, Kleine–Levin syndrome, forms of autism or schizoid personality disorder.[33] However, the prevalence of SCT in these clinical populations has yet to be empirically and systematically investigated.

Treatment

Treatment of SCT has not been well investigated. Initial drug studies were done only with the ADHD medication methylphenidate (e.g. Ritalin®), and even then only with children who were diagnosed as ADD without hyperactivity (using DSM-III criteria) and not specifically for SCT. The research seems to have found that most children with ADD (attention deficit disorder) with Hyperactivity (currently ADHD combined type) responded well at medium-to-high doses.[23] However, a sizable percentage of children with ADD without hyperactivity (currently ADHD inattentive type, therefore the results may apply to SCT) did not gain much benefit from methylphenidate, and when they did benefit, it was at a much lower dose.[34]

However, one study and a retrospective analysis of medical histories found that the presence or absence of SCT symptoms made no difference in response to methylphenidate in children with ADHD-I.[35][9] But these studies did not specifically and explicitly examine the effect of the drug on SCT symptoms in children. The medication studies who did this found atomoxetine (Strattera) to have significant beneficial effects that were independent of ADHD symptoms[36] and a poor response for methylphenidate.[5]

Only one study has investigated the use of behavior modification methods at home and school for children with predominantly SCT symptoms and it found good success.[37]

In April 2014, The New York Times reported that sluggish cognitive tempo is the subject of pharmaceutical company clinical drug trials, including ones by Eli Lilly that proposed that one of its biggest-selling drugs, Strattera, could be prescribed to treat proposed symptoms of sluggish cognitive tempo.[38] Other researchers believe that there is no effective treatment for SCT.[1]

Prognosis

The prognosis of SCT is unknown. In contrast, much is known about the adolescent and adult outcomes of children having ADHD. Those with SCT symptoms typically show a later onset of their symptoms than do those with ADHD, perhaps by as much as a year or two later on average. Both groups had similar levels of learning problems and inattention, but SCT children had less externalizing symptoms and higher levels of unhappiness, anxiety/depression, withdrawn behavior, and social dysfunction. They do not have the same risks for oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, or social aggression and thus may have different life course outcomes compared to children with ADHD-HI and Combined subtypes who have far higher risks for these other "externalizing" disorders.[9]

However, unlike ADHD, there are no longitudinal studies of children with SCT that can shed light on the developmental course and adolescent or adult outcomes of these individuals.

Epidemiology

Recent studies indicate that the symptoms of SCT in children form two dimensions: daydreamy-spacey and sluggish-lethargic, and that the former are more distinctive of the disorder from ADHD than the latter.[39][40] This same pattern was recently found in the first study of adults with SCT by Barkley and also in more recent studies of college students.[9] These studies indicated that SCT is probably not a subtype of ADHD but a distinct disorder from it. Yet it is one that overlaps with ADHD in 30–50% of cases of each disorder, suggesting a pattern of comorbidity between two related disorders rather than subtypes of the same disorder. Nevertheless, SCT is strongly correlated with ADHD inattentive and combined subtypes.[39] According to a Norwegian study, "SCT correlated significantly with inattentiveness, regardless of the subtype of ADHD."[41]

History

Early observations

There have been descriptions in literature for centuries of children who are very inattentive and prone to foggy thought.

Symptoms similar to ADHD were first systematically described in 1775 by Melchior Adam Weikard and in 1798 by Alexander Crichton in their medical textbooks. Although Weikard mainly described a single disorder of attention resembling the hyperactive-impulsive subtype of ADHD, Crichton postulates an additional attention disorder, described as a "morbid diminution of its power or energy", and further explores possible "corporeal" and "mental" causes for the disorder (including "irregularities in diet, excessive evacuations, and the abuse of corporeal desires"). However, he does not further describe any symptoms of the disorder, making this an early but certainly non-specific reference to an SCT-like syndrome.[42][9]

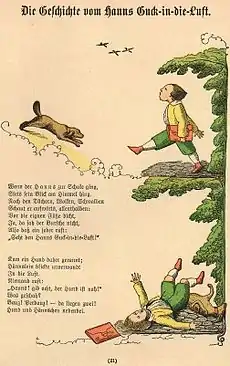

One example from fictional literature is Heinrich Hoffmann's character of "Johnny Head-in-Air" (Hanns Guck-in-die-Luft), in Struwwelpeter (1845). (Some researchers see several characters in this book as showing signs of child psychiatric disorders).[43]

The Canadian pediatrician Guy Falardeau, besides working with hyperactive children, also wrote about very dreamy, quiet and well-behaved children that he encountered in his practice.[44]

First research efforts

In more modern times, research surrounding attention disorders has traditionally focused on hyperactive symptoms, but began to newly address inattentive symptoms in the 1970s. Influenced by this research, the DSM-III (1980) allowed for the first time a diagnosis of an ADD subtype that presented without hyperactivity. Researchers exploring this subtype created rating scales for children which included questions regarding symptoms such as short attention span, distractibility, drowsiness, and passivity.[7] In the mid-1980s, it was proposed that as opposed to the then accepted dichotomy of ADD with or without hyperactivity (ADD/H, ADD/noH), instead a three-factor model of ADD was more appropriate, consisting of hyperactivity-impulsivity, inattention-disorganization, and slow tempo subtypes.[45]

In the 1990s, Weinberg and Brumback proposed a new disorder: "primary disorder of vigilance" (PVD). Characteristic symptoms of it were difficulty sustaining alertness and arousal, daydreaming, difficulty focusing attention, losing one's place in activities and conversation, slow completion of tasks and a kind personality. The most detailed case report in their article looks like a prototypical representation of SCT. The authors acknowledged an overlap of PVD and ADHD but argued in favor of considering PVD to be distinct in its unique cognitive impairments.[46][47] Problematic with the paper is that it dismissed ADHD as a nonexistent disorder (despite it having several thousand research studies by then) and preferred the term PVD for this SCT-like symptom complex. A further difficulty with the PVD diagnosis is that not only is it based merely on 6 cases instead of the far larger samples of SCT children used in other studies but the very term implies that science has established the underlying cognitive deficits giving rise to SCT symptoms, and this is hardly the case.[9]

With the publication of DSM-IV in 1994, the disorder was labeled as ADHD, and was divided into three subtypes: predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, and combined. Of the proposed SCT-specific symptoms discussed while developing the DSM-IV, only "forgetfulness" was included in the symptom list for ADHD-I, and no others were mentioned. However, several of the proposed SCT symptoms were included in the diagnosis of "ADHD, not otherwise specified".[7]

Prior to 2001, there were a total of four scientific journal articles specifically addressing symptoms of SCT. But then a researcher suggested that sluggish tempo symptoms (such as inconsistent alertness and orientation) were, in fact, adequate for the diagnosis of ADHD-I. Thus, he argued, their exclusion from DSM-IV was inappropriate.[48] The research article and its accompanying commentary urging the undertaking of more research on SCT spurred the publication of over 30 scientific journal articles to date which specifically address symptoms of SCT.[7]

However, with the publication of DSM-5 in 2013, ADHD continues to be classified as predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, and combined type and there continues to be no mention of SCT as a diagnosis or a diagnosis subtype anywhere in the manual. The diagnosis of "ADHD, not otherwise specified" also no longer includes any mention of SCT symptoms.[11] Similarly, ICD-10, the medical diagnostic manual, has no diagnosis code for SCT. Although SCT is not recognized as a disorder at this point, researchers continue to debate its usefulness as a construct and its implications for further attention disorder research.[7]

Controversy

Significant skepticism has been raised within the medical and scientific communities as to whether SCT, currently considered a "symptom cluster," actually exists as a distinct disorder.[38]

Dr. Allen Frances, an emeritus professor of psychiatry at Duke University, has commented "We're seeing a fad in evolution: Just as ADHD has been the diagnosis du jour for 15 years or so, this is the beginning of another. This is a public health experiment on millions of kids...I have no doubt there are kids who meet the criteria for this thing, but nothing is more irrelevant. The enthusiasts here are thinking of missed patients. What about the mislabeled kids who are called patients when there's nothing wrong with them? They are not considering what is happening in the real world."[38]

UCLA researcher and Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology editorial board member Steve S. Lee has also expressed concern based on SCT's close relationship to ADHD, cautioning that a pattern of over-diagnosis of the latter has "already grown to encompass too many children with common youthful behavior, or whose problems are derived not from a neurological disorder but from inadequate sleep, a different learning disability or other sources." Lee states, "The scientist part of me says we need to pursue knowledge, but we know that people will start saying their kids have [sluggish cognitive tempo], and doctors will start diagnosing it and prescribing for it long before we know whether it's real...ADHD has become a public health, societal question, and it's a fair question to ask of SCT."[38]

Adding to the controversy are potential conflicts of interest among the condition's proponents, including the funding of prominent SCT researchers' work by the global pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly[38] and, in the case of Dr. Russell Barkley, a leader in the burgeoning SCT research field, direct financial ties to that company (Dr. Barkley has received $118,000 from 2009 to 2012 for consulting and speaking engagements from Eli Lilly).[49] When referring to the "increasing clinical referrals occurring now and more rapidly in the near future driven by increased awareness of the general public in SCT", Dr. Barkley writes "The fact that SCT is not recognized as yet in any official taxonomy of psychiatric disorders will not alter this circumstance given the growing presence of information on SCT at various widely visited internet sites such as YouTube and Wikipedia, among others."[50]

See also

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder controversies

- Bradyphrenia (slowness of thought)

- Clouding of consciousness

- Cognitive Tempo

- Sluggish schizophrenia

- Type B personality

References

- Mary Silva (Cincinnati Children's Hospital 2015). A Fuzzy Debate About A Foggy Condition. Megan Brooks (Medscape 2014). Sluggish Cognitive Tempo a Distinct Attention Disorder?

- Martha A. Combs; et al. (2014). "Impact of SCT and ADHD Symptoms on Adults' Quality of Life". Applied Research in Quality of Life. 9 (4): 981–995. doi:10.1007/s11482-013-9281-3. S2CID 49480261.

- Becker, Stephen P.; Holdaway, Alex S.; Luebbe, Aaron M. (2018). "Suicidal Behaviors in College Students: Frequency, Sex Differences, and Mental Health Correlates Including Sluggish Cognitive Tempo". Journal of Adolescent Health. 63 (2): 181–188. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.02.013. PMC 6118121. PMID 30153929.

- "Sluggish cognitive tempo (Chapter 15)". Oxford textbook of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (First ed.). Oxford Publishing. 2018. pp. 147–154. ISBN 9780191059766.

- Fırat, Sumeyra (2020). "An Open-Label Trial of Methylphenidate Treating Sluggish Cognitive Tempo, Inattention, and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity Symptoms Among 6- to 12-Year-Old ADHD Children: What Are the Predictors of Treatment Response at Home and School?". Journal of Attention Disorders. 25 (9): 1321–1330. doi:10.1177/1087054720902846. PMID 32064995. S2CID 211134241.

- Caryn Carlson, Miranda Mann (2002). "Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Predicts a Different Pattern of Impairment in the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Predominantly Inattentive Type". Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 31 (1): 123–129. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3101_14. PMID 11845644. S2CID 6212568.

- Stephen P. Becker; et al. (2014). "Sluggish cognitive tempo in abnormal child psychology: an historical overview and introduction to the special section". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 42 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9825-x. PMID 24272365. S2CID 25310726.

- Silverstein, Michael J. (2019). "The Characteristics and Unique Impairments of Comorbid Adult ADHD and Sluggish Cognitive Tempo: An Interim Analysis". Psychiatric Annals. 49 (10): 457–465. doi:10.3928/00485713-20190905-01. S2CID 208396893.

- Russell A. Barkley (2015). Sluggish Cognitive Tempo or Concentration Deficit Disorder (Free Fulltext). Oxford Handbooks Online. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935291.013.9. ISBN 978-0-19-993529-1.

- Becker, Stephen; Willcutt, Erik; Leopold, Daniel; Fredrick, Joseph; Smith, Zoe; Jacobson, Lisa; Burns, G Leonard; Mayes, Susan; Waschbusch, Daniel; Froehlich, Tanya; McBurnett, Keith; Servera, Mateu; Barkley, Russell (21 August 2022). "Report of a Work Group on Sluggish Cognitive Tempo: Key Research Directions and a Consensus Change in Terminology to Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: S0890–8567(22)01246-1. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2022.07.821. PMID 36007816. S2CID 251749516. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- APA (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth ed.). ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8. pp. 59–65.

- "ADHD: Symptoms and Diagnosis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017). 2018-12-20.

- Stephen P. Becker; et al. (2016). "The Internal, External, and Diagnostic Validity of Sluggish Cognitive Tempo: A Meta-Analysis and Critical Review". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 55 (3): 163–178. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2015.12.006. PMC 4764798. PMID 26903250.

- Russell A. Barkley (2018). Barkley Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Scale—Children and Adolescents (BSCTS-CA). New York: Guilford. pp. 95–96. ISBN 9781462535187.

- Russel A. Barkley (2013): Two Types of Attention Disorders Now Recognized by Clinical Scientists. In: Taking Charge of ADHD: The Complete, Authoritative Guide for Parents. Guilford Press (3rd ed.), p.150. ISBN 978-1-46250-789-4.

- Stephen P. Becker; et al. (2013). "Reward and punishment sensitivity are differentially associated with ADHD and sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms in children". Journal of Research in Personality. 47 (6): 719–727. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2013.07.001.

- Weiler, Michael David; Bernstein, Jane Holmes; Bellinger, David; Waber, Deborah P. (2002). "Information Processing Deficits in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Inattentive Type, and Children with Reading Disability". Journal of Learning Disabilities. 35 (5): 449–462. doi:10.1177/00222194020350050501. PMID 15490541. S2CID 35656571.

- Ramsay, J. Russell (2014). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult ADHD: An integrative psychosocial and medical approach (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0415955003.

The classic presentation of ADHD involves features of high distractibility and poor attention vigilance, which can be considered as examples of attention and sustained concentration being engaged but then punctuated or interrupted. In contrast, SCT/CDD is characterized by difficulties orienting and engaging attention, effort, and alertness in the first place.

- Mary V. Solanto (2007). "Neurocognitive Functioning in AD/HD, Predominantly Inattentive and Combined Subtypes". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 35 (5): 729–44. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9123-6. PMC 2265203. PMID 17629724.

Differences between subtypes in cognitive tempo point to potentially important differences in the qualitative features of inattention, which suggest differences in etiology. Thus, whereas children with predominantly inattentive type (PI) appear to be slow to orient and slow to respond to cognitive and social stimuli in their immediate surroundings, children with combined type (CB) rapidly orient to novel external stimuli regardless of relevance. A series of studies in children who would now be classified as CB failed to identify deficits in the stimulus input stages of information-processing (Sergeant, 2005). The observably more sluggish orientation and response style of the child with PI by contrast, does suggest deficits in these early attentional processes.

- Kim, Kiho (2020). "Normal executive attention but abnormal orienting attention in individuals with sluggish cognitive tempo". International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 21 (1): S1697260020300673. doi:10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.08.003. PMC 7753035. PMID 33363582.

- Stephen P. Becker; et al. (2014). "Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Dimensions and Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Symptoms in Relation to College Students' Sleep Functioning". Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 45 (6): 675–685. doi:10.1007/s10578-014-0436-8. PMID 24515313. S2CID 39379796.

- Barbara A. Wilson (2003). "Behavioural Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome (BADS)" (PDF). Journal of Occupational Psychology, Employment and Disability. 5 (2): 33–37. ISSN 1740-4193.

- Adele Diamond (2005). "ADD (ADHD without hyperactivity): a neurobiologically and behaviorally distinct disorder from ADHD with hyperactivity". Dev. Psychopathol. 17 (3): 807–25. doi:10.1017/S0954579405050388. PMC 1474811. PMID 16262993.

- Sara Moruzzi (2014). "A Twin Study of the Relationships among Inattention, Hyperactivity/Impulsivity and Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Problems" (PDF). Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 42 (1): 63–75. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9725-0. PMID 23435481. S2CID 4201578. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-15.

- Catherine Fassbender; et al. (2015). "Differentiating SCT and inattentive symptoms in ADHD using fMRI measures of cognitive control" (PDF). NeuroImage: Clinical. 8: 390–397. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2015.05.007. PMC 4474281. PMID 26106564. S2CID 14301089. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-04-17.

- Sunyer, Jordi; Dolz, Montserrat; Ribas, Núria; Forns, Joan; Batlle, Santiago; Medrano-Martorell, Santiago; Blanco-Hinojo, Laura; Martínez-Vilavella, Gerard; Camprodon-Rosanas, Ester (2018). "Brain Structure and Function in School-Aged Children With Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Symptoms". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 58 (2): 256–266. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2018.09.441. hdl:10230/43715. PMID 30738552. S2CID 73436796.

- Stephen Becker; et al. (2012). "A preliminary investigation of the relation between thyroid functioning and sluggish cognitive tempo in children". Journal of Attention Disorders. 21 (3): 240–246. doi:10.1177/1087054712466917. PMID 23269197. S2CID 3019228.

- Diana M. Graham (2013). "Prenatal Alcohol Exposure, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, and Sluggish Cognitive Tempo" (PDF). Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 37 (Suppl 1): 338–346. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01886.x. PMC 3480974. PMID 22817778.

- Cara B. Reeves (2007). "Brief Report: Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Among Pediatric Survivors of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia". Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 32 (9): 1050–1054. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.485.7214. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsm063. PMID 17933846.

- Stephen Becker et al.: Concentration Inventory for Children and Adults.

- Randy W. Kamphaus; Paul J. Frick (2005). Clinical Assessment of Child And Adolescent Personality And Behavior. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 395. ISBN 978-0-387-26300-7.

- "Hyperkinetic disorders (F90)" (PDF). ICD-10 – Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. WHO (2010). p. 206.

In recent years the use of the diagnostic term attention deficit disorder" for these syndromes has been promoted. It has not been used here because it implies a knowledge of psychological processes that is not yet available, and it suggests the inclusion of anxious, preoccupied, or "dreamy" apathetic children whose problems are probably different.

- Schizoid Personality Disorder, Associated features (PDF). Vol. DSM-III (1980). 14 March 1985. p. 310. ISBN 978-0521315289. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-02.

Individuals with this disorder are often unable to express aggressiveness or hostility. They may seem vague about their goals, indecisive in their actions, self-absorbed, absentminded, and detached from their environment (not with it or in a fog). Excessive daydreaming is often present.

- Russell A. Barkley, George DuPaul (1991). "Attention deficit disorder with and without hyperactivity: clinical response to three dose levels of methylphenidate". Pediatrics. 87 (4): 519–531. doi:10.1542/peds.87.4.519. PMID 2011430. S2CID 23501657.

- Henrique T. Ludwig (2009). "Do Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Symptoms Predict Response to Methylphenidate in Patients with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder–Inattentive Type?". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 19 (4): 461–465. doi:10.1089/cap.2008.0115. PMID 19702499.

- Keith McBurnett (2016). "Atomoxetine-Related Change in Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Is Partially Independent of Change in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Inattentive Symptoms". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 27 (1): 38–42. doi:10.1089/cap.2016.0115. PMID 27845858.

- Linda Pfiffner (2007). "A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Integrated Home-School Behavioral Treatment for ADHD, Predominantly Inattentive Type". J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 46 (8): 1041–1050. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e318064675f. PMID 17667482.

- Alan Schwarz (April 11, 2014). "Idea of New Attention Disorder Spurs Research, and Debate". The New York Times.

- Erik G. Willcutt (2013). "The Internal and External Validity of Sluggish Cognitive Tempo and its Relation with DSM–IV ADHD". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 42 (1): 21–35. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9800-6. PMC 3947432. PMID 24122408.

- Ann Marie Penny (2009). "Developing a measure of sluggish cognitive tempo for children: Content validity, factor structure, and reliability". Psychological Assessment. 21 (3): 380–389. doi:10.1037/a0016600. PMID 19719349.

- Benedicte Skirbekk; et al. (2011). "The relationship between sluggish cognitive tempo, subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and anxiety disorders". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 39 (4): 513–525. doi:10.1007/s10802-011-9488-4. hdl:10852/28063. PMID 21331639. S2CID 5506067.

- Alexander Crichton (1798). "Chapter 2. On Attention, and its diseases". An inquiry into the nature and origin of mental derangement.

- Mark A. Stewart (1970). "Hyperactive children". Scientific American. 222 (4): 94–98. Bibcode:1970SciAm.222d..94S. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0470-94. PMID 5417827.

- Guy Falardeau (1997). Les enfants hyperactifs et lunatiques. ISBN 978-2890446267.

- Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Schaughency EA, Atkins MS, Murphy A, Hynd G (1988). "Dimensions and Types of Attention Deficit Disorder". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 27 (3): 330–335. doi:10.1097/00004583-198805000-00011. PMID 3379015.

- Keith McBurnett (2007). "Sluggish Cognitive Tempo: The Promise and Problems of Measuring Syndromes in the Attention Spectrum". In McBurnett, Keith; Pfiffner, Linda (eds.). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder – Concepts, Controversies, New Directions. Medical Psychiatry. p. 352. doi:10.3109/9781420017144. ISBN 978-0-8247-2927-1.

- Warren Weinberg, Roger Brumback (1990). "Primary disorder of vigilance: A novel explanation of inattentiveness, daydreaming, boredom, restlessness, and sleepiness". The Journal of Pediatrics. 116 (5): 720–725. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82654-x. PMID 2329420.

- Keith McBurnett; et al. (2001). "Symptom properties as a function of ADHD type: An argument for continued study of sluggish cognitive tempo". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 29 (3): 207–213. doi:10.1023/A:1010377530749. PMID 11411783. S2CID 9758381.

- "Has Your Health Professional Received Drug Company Money?". ProPublica. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- Barkley, R. A. (2014). "Sluggish Cognitive Tempo (Concentration Deficit Disorder?): Current Status, Future Directions, and a Plea to Change the Name" (PDF). Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 42 (1): 117–125. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9824-y. PMID 24234590. S2CID 8287560.

External links

- ADHD in Adults: Sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD