Sole (foot)

The sole is the bottom of the foot.

| Sole | |

|---|---|

Soles of a human's feet | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Foot |

| Artery | medial plantar, lateral plantar |

| Nerve | medial plantar, lateral plantar |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | planta |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.044 |

| TA2 | 337 |

| FMA | 25000 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In humans the sole of the foot is anatomically referred to as the plantar aspect.

Structure

The glabrous skin on the sole of the foot lacks the hair and pigmentation found elsewhere on the body, and it has a high concentration of sweat pores. The sole contains the thickest layers of skin on the body due to the weight that is continually placed on it. It is crossed by a set of creases that form during the early stages of embryonic development. Like those of the palm, the sweat pores of the sole lack sebaceous glands.

The sole is a sensory organ by which we can perceive the ground while standing and walking. The subcutaneous tissue in the sole has adapted to deal with the high local compressive forces on the heel and the ball (between the toes and the arch) by developing a system of "pressure chambers." Each chamber is composed of internal fibrofatty tissue covered by external collagen connective tissue. The septa (internal walls) of these chambers are permeated by numerous blood vessels, making the sole one of the most vascularized, or blood-enriched, regions in the human body. [1]

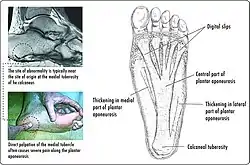

The sole and the longitudinal arch of the foot are supported by a thick connective tissue, the plantar fascia. The central component of this tissue extends to the supporting bones and gives two divisions–the medial component and lateral component; thus they define the boundaries of the three muscle compartments of the sole (see below).[2]

The bones underlying the sole form the arch of the foot. The arches might collapse later in life, resulting in flat feet.

Intrinsic

The intrinsic muscles in the sole are grouped in four layers:

In the first layer, the flexor digitorum brevis is the large central muscle located immediately above the plantar aponeurosis. It flexes the second to fifth toes and is flanked by abductor hallucis and abductor digiti minimi.[2]

In the second layer, the quadratus plantae, located below flexor digitorum brevis, inserts into the tendon of flexor digitorum longus on which the lumbricals originate.[2]

In the third layer, the oblique head of adductor hallucis joins the muscle's transversal head on the lateral side of the big toe. Medially to adductor hallucis are the two heads of flexor hallucis brevis, deep to the tendon of flexor hallucis longus. The considerably smaller flexor digiti minimi brevis on the lateral side can be mistaken for one of the interossei.[2]

In the fourth layer. the dorsal and plantar interossei are located between and below the metatarsal bones and act as antagonists.[2]

The central compartment is shared by the lumbricals, quadratus plantae, flexor digitorum brevis, and adductor hallucis; the medial compartment by abductor hallucis, flexor hallucis brevis, abductor digiti minimi, flexor digiti minimi brevis, and opponens digiti minimi (often considered part of the former muscle); whilst the lateral compartment is occupied by extensor digitorum brevis and extensor hallucis brevis. [3]

Extrinsic

The tendons of several extrinsic foot muscle reach the sole:

- The tendons of the deep foot flexors in the posterior compartment of the leg, tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, and flexor hallucis longus, passes behind the medial malleolus into the sole.

- The tendon of fibularis longus similarly passes behind the lateral malleolus into the sole.[4]

Nerve supply

The soles of the feet are extremely sensitive to touch due to a high concentration of nerve endings, with as many as 200,000 per sole.[5] This makes them sensitive to surfaces that are walked on, ticklish and some people find them to be erogenous zones.[6]

Medically, the soles are the site of the plantar reflex, the testing of which can be painful due to the sole's sensitivity.

The deep fibular nerve from the common fibular nerve provides the sensory innervation of the skin between the first and second toes and the motor innervation of the muscles of the anterior compartment of the leg and dorsal foot. Damage to the deep fibular nerve can result in foot drop.[7]

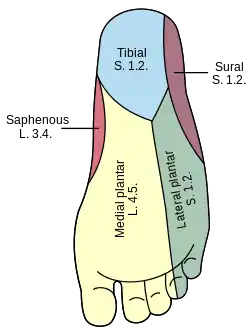

The plantar digital nerves from the medial plantar nerve provide sensory innervation to the skin of the plantar aspect of the toes, except for the medial part of the big toe and the lateral part of the little toe and the motor innervation of the first lumbrical.[7]

The proper plantar nerve from the common plantar digital nerve provides sensory innervation to the plantar surface of the toes as well as the dorsal aspect of the distal interphalangeal phalanges. It also provides motor innervation to flexor hallucis brevis.[7]

The superficial and deep branches of the lateral plantar nerve from the tibial nerve provide sensory innervation to the skin of the lateral side of the sole, to the fifth and half the fourth toes, and the nail bed of these toes. They also provide motor innervation to quadratus plantae, abductor digiti minimi, flexor digiti minimi brevis, lateral three lumbricals, adductor hallucis, and the dorsal and plantar interossei.[7]

The medial plantar nerve from the tibial nerve provides sensory innervation to the skin of the medial side of the sole, the skin of the medial three and a half toes, and the nail beds of these toes. It also provides motor innervation to abductor hallucis, flexor hallucis brevis, flexor digitorum brevis, and the first lumbrical.[7]

The saphenous nerve from the femoral nerve provides sensory innervation to the medial side of the foot as well as the medial side of the leg. Likewise, the sural nerve provides sensory innervation to the skin on the lateral side of the foot as well as the skin on the posterior aspect of the lower leg.[7]

The tibial nerve from the sciatic nerve provides sensory innervation to the skin of the sole and toes, and the dorsal aspect of the toes. It provides motor innervation to plantaris, tibialis posterior, flexor hallucis longus, flexor digitorum longus as well as posterior muscles in the leg.[7]

Society and culture

The purpose of protecting the sole against uncomfortable and harmful impacts of the environment during locomotion initiated the general introduction of footwear in early human history. The achieved protection of the susceptible soles provided for faster and considerably more efficient movement particularly in adverse environmental terrains as against walking or running on bare feet.

The sensitivity of the sole makes it an objective for a sensual touch, tickling or sexual stimulation and also a target for means of corporal punishment.[8]

The beating of the soles of a person's bare feet (foot whipping or "bastinado") with specific objects such as rods and canes has hereby served as a means of corporal punishment and discipline in various civilizations to this day. The application of this measure is mostly found in prisons and similar institutions, such as schools and reformatories. It is also a common method of physical torture.

In Thailand, Saudi Arabia, and some Muslim countries it is considered offensive to sit raising the leg so the uncovered sole of the foot is visible and therefore taboo.[9]

Other animals

Terrestrial animals using their soles for locomotion are called plantigrade.

In chimpanzees, the soles are furrowed with creases deeper and more distinct than in their palms. In the palms, the pattern density is thickest in the central part, but in the sole, the density is thickest near the big toe whilst a large part of the remaining sole is covered by thick, tight, and smooth skin almost without furrows.[10]

In bonobos, the pattern intensity of the epidermal ridges (i.e. "fingerprints") of the palms and soles is considerably higher than in chimpanzees. Whilst the pattern intensity in the palm is the highest of all species of apes, in the sole, the density decreases and is comparable to other apes.[11]

Clinical significance

The sole is subject to many skin diseases.

See also

Notes

- Ross & Lamperti 2006, pp. 418, 486

- Ross & Lamperti 2006, pp. 456–61

- Ross & Lamperti 2006, pp. 438–40

- Ross & Lamperti 2006, pp. 433, 436–37

- "nerve endings - barefootr". barefootr.com. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Brittan 2003

- Tank 2006, Nerves of the Sole of the Foot

- Rossi 1993

- Lumsden, Lumsden & Weithoff 2009, p. 223

- Ladygina-Kohts 2002, pp. 29–33

- Brehme 1975, Abstract

References

- Brehme, H. (March 1975). "Epidermal patterns of the hands and feet of the pygmy Chimpanzee (Pan paniscus)". Am J Phys Anthropol. 42 (2): 255–62. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330420214. PMID 1119549.

- Brittan, Patti (2003). Complete Idiot's Guide to Sensual Massage. Alpha Books. ISBN 9781592570959.

- Ladygina-Kohts, N.N. (2002). de Waal, Frans B.M. (ed.). Infant Chimpanzee and Human Child: A Classic 1935 Comparative Study of Ape Emotions and Intelligence. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195135657.

- Lumsden, Gay; Lumsden, Donald; Weithoff, Carolyn (2009). Communicating in Groups and Teams: Sharing Leadership. Wadsworth Publishing. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-495-57046-2. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- Ross, Lawrence M.; Lamperti, Edward D., eds. (2006). Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme. ISBN 1-58890-419-9.

- Rossi, William A. (1993). The Sex Life of the Foot and Shoe. Kreiger Publishing. ISBN 9780894645730.

- Tank, Patrick W. (2006). "Sole of the Foot". University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

- Young, Craig C.; Niedfeldt, Mark W.; Morris, George A.; Eerkes, Kevin J. (2005). "Clinical Examination of the Foot and Ankle" (PDF). Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 32 (1): 105–32. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2004.11.002. PMID 15831315.