Subglottic stenosis

Subglottic stenosis is a congenital or acquired narrowing of the subglottic airway.[1] It can be congenital, acquired, iatrogenic, or very rarely, idiopathic. It is defined as the narrowing of the portion of the airway that lies between the vocal cords and the lower part of the cricoid cartilage. In a normal infant, the subglottic airway is 4.5-5.5 millimeters wide, while in a premature infant, the normal width is 3.5 millimeters. Subglottic stenosis is defined as a diameter of under 4 millimeters in an infant. Acquired cases are more common than congenital cases due to prolonged intubation being introduced in the 1960s.[2] It is most frequently caused by certain medical procedures or external trauma, although infections and systemic diseases can also cause it.

| Subglottic stenosis | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Neck AP x-ray of patient with post-intubation subglottic stenosis, as shown by the narrowing in the tracheal lumen marked by the arrow. | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

| Symptoms | Difficulty breathing |

| Usual onset | Any |

| Causes | Intubation, trauma, systemic diseases, cancer |

| Risk factors | Prolonged intubation, nasogastric tube |

| Diagnostic method | CT scan, MRI, OCT |

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms may range from stridor during exercise to complete obstruction of the airway. In idiopathic cases, symptoms may be mistaken for asthma. In congenital cases, symptoms occur soon after birth, and include difficulty breathing, stridor, and air hunger. If the vocal cords are affected, symptoms may include inability to make sound, and an unusual cry.[2]

Causes

Most commonly, acquired cases are caused by trauma or certain medical procedures. The condition is more often caused by external trauma in adults. External injuries occur from vehicular accidents or clothesline injuries.[2] Iatrogenic cases can occur from intubation, tracheostomy, and an endotracheal tube cuff pressure that is too high.[3] 17 hours of intubation in adults and 1 week of intubation in neonates can cause the injury. Infants born prematurely can be intubated for a longer amount of time due to the fact that they have more flexible cartilage and a larynx located high in the airway. 90% of acquired cases in children are due to intubation, due to the ring of cartilage in the upper airway.[2] Less commonly, infections, such as bacterial tracheitis, tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, diphtheria, and laryngeal papillomatosis can cause it. Systemic diseases, such as amyloidosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, scleroderma, relapsing polychondritis, and polyarthritis, can also cause it. Other causes may include aspiration of foreign bodies, burns, and exposure to occupational hazards.[3] Very rarely, the condition may also have no known cause, in which case it is known as idiopathic subglottic stenosis.[2]

Mechanism

High cuff pressure or long-term intubation can cause damage to the tracheal mucosa, causing inflammation, ulceration, and breakdown of cartilage.[3] When the injury heals, scarring occurs, narrowing the airway.[4] Treatment-related risk factors include repeated intubation, the presence of a nasogastric tube, and size of an endotracheal tube. Person-related risk factors include systemic diseases, the likelihood of infection, and inadequate perfusion. Acid reflux may cause narrowing due to scarring resulting from stomach acid damaging the tracheal mucosa. 10-23% of causes result due to narrowing arising from granulomatosis with polyangiitis. In these cases, it is believed that this is more common in people under the age of 20. Around 66% of sarcoidosis cases involve the airway.[3]

Diagnosis

CT scans and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) can help in diagnosis. X-rays can determine the location and size of the narrowed airway portion. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) can help observe the progression of the injury. Esophageal pH monitoring can help detect any acid reflux, which can worsen the condition. An endoscope can be inserted and used to see the vocal cords, airway, and esophagus. Spirometry is a useful way to measure respiratory function. People affected by subglottic stenosis have a FEV1 of over 10.[2]

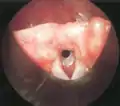

Subglottic stenosis is graded according to the Cotton-Myer classification system from one to four based on the severity of the blockage. Grade 1 is up to 50% obstruction, Grade 2 is 50-70% obstruction, Grade 3 is 70-99% obstruction, and Grade 4 is with no visible lumen.[5]

Grade 1 subglottic stenosis

Grade 1 subglottic stenosis Grade 2 subglottic stenosis

Grade 2 subglottic stenosis Grade 3 subglottic stenosis

Grade 3 subglottic stenosis Grade 4 subglottic stenosis

Grade 4 subglottic stenosis

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to relieve any breathing difficulty and to ensure that the airway remains open in the long term. In mild cases, the disease can be treated with endoscopic balloon dilation. In severe cases, open surgery is done. Owing to the risk of complications, tracheostomy is avoided if possible.[2]

Surgery

In severe cases, the condition frequently recurs after dilation, and the main treatment is open surgery. There are three main surgical procedures that are used when treating subglottic stenosis. These include endoscopy, open neck surgery, and tracheotomy. Endoscopic procedures include dilation via balloon or rigid, incision via laser, and stent placement.[2]

Other

In mild cases, such as cases with only granuloma or thin, web-like tissue, dilation is able to remove the lesion. In severe cases, dilation and laser treatment only works temporarily, and the condition frequently recurs. Repeated procedures, especially stents, come with the risk of increasing the damaged area. Also, laser resection has a risk of damaging the cartilage underneath. For this reason, surgery is typically done.[6] In addition to surgery, mitomycin can be applied topically and glucocorticoids can be injected.[2]

Idiopathic cases are usually treated via endoscopic balloon dilation, and dilation may be improved by injecting corticosteroids. It is also the safest and main treatment in pregnant women. It allows dilation via noninvasive measures such as expanding a balloon catheter via ventilation.[2]

Prognosis

The condition frequently recurs after dilation. The prognosis after surgery is good if it is done carefully to avoid complications.[2]

Epidemiology

The condition has decreased in frequency over time, due to improved management of people on a ventilator. The condition occurs in around 1% of endotracheal tube users.[4]

References

- "Subglottic Stenosis in Adults: Problem, Etiology, Pathophysiology". 2017-06-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Jagpal, Nitish; Shabbir, Nadeem (2021), "Subglottic Stenosis", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 33085412, retrieved 2021-07-27

- Aravena, Carlos; Almeida, Francisco A.; Mukhopadhyay, Sanjay; Ghosh, Subha; Lorenz, Robert R.; Murthy, Sudish C.; Mehta, Atul C. (March 2020). "Idiopathic subglottic stenosis: a review". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 12 (3): 1100–1111. doi:10.21037/jtd.2019.11.43. ISSN 2072-1439. PMC 7139051. PMID 32274178.

- Marston, Alexander P.; White, David R. (2018-12-01). "Subglottic Stenosis". Clinics in Perinatology. 45 (4): 787–804. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2018.07.013. ISSN 0095-5108. PMID 30396418. S2CID 53235038.

- Myer Cm, 3rd; O'Connor, D. M.; Cotton, R. T. (April 1994). "Proposed grading system for subglottic stenosis based on endotracheal tube sizes". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. 103 (4 Pt 1): 319–23. doi:10.1177/000348949410300410. PMID 8154776. S2CID 12782910.

- D’Andrilli, Antonio; Venuta, Federico; Rendina, Erino Angelo (March 2016). "Subglottic tracheal stenosis". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 8 (Suppl 2): S140–S147. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2016.02.03. ISSN 2072-1439. PMC 4775266. PMID 26981264.