Submandibular gland

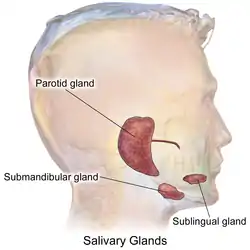

The paired submandibular glands (historically known as submaxillary glands) are major salivary glands located beneath the floor of the mouth. They each weigh about 15 grams and contribute some 60–67% of unstimulated saliva secretion; on stimulation their contribution decreases in proportion as the parotid secretion rises to 50%.[1] The average length of the normal human submandibular salivary gland is approximately 27mm, while the average width is approximately 14.3mm.[2]

| Submandibular gland | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Details | |

| Artery | glandular branches of facial artery |

| Nerve | submandibular ganglion |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | glandula submandibularis |

| MeSH | D013363 |

| TA98 | A05.1.02.011 |

| TA2 | 2810 |

| FMA | 55093 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

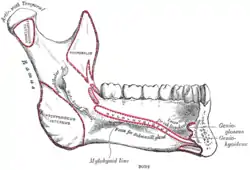

Lying superior to the digastric muscles, each submandibular gland is divided into superficial and deep lobes, which are separated by the mylohyoid muscle:[3]

- The superficial lobe comprises most of the gland, with the mylohyoid muscle runs under it

- The deep lobe is the smaller part

Secretions are delivered into the submandibular duct on the deep portion after which they hook around the posterior edge of the mylohyoid muscle and proceed on the superior surface laterally. The excretory ducts are then crossed by the lingual nerve, and ultimately drain into the sublingual caruncles – small prominences on either side of the lingual frenulum along with the major sublingual duct. The gland can be bilaterally palpated (felt) inferior and posterior to the body of the mandible, moving inward from the inferior border of the mandible near its angle with the head tilted forwards.[4]

Microanatomy

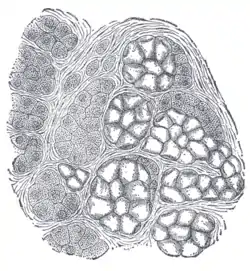

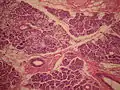

Lobes contain smaller lobules, which contain adenomeres, the secretory units of the gland. Each adenomer contains one or more acini, or alveoli, which are small clusters of cells that secrete their products into a duct. The acini of each adenomere are composed of either serous or mucous cells, with serous adenomeres predominating. Some mucous adenomeres may also be capped with a serous demilune, a layer of lysozyme-secreting serous cells resembling a half moon.

Like other exocrine glands, the submandibular gland can be classified by the microscopic anatomy of its secretory cells and how they are arranged. Because the glands are branched, and because the tubules forming the branches contain secretory cells, submandibular glands are classified as branched tubuloacinar glands. Further, because the secretory cells are of both serous and mucous types, the submandibular gland is a mixed gland, and though most of the cells are serous, the exudate is chiefly mucous. It has long striated ducts and short intercalated ducts.[5]

The secretory acinar cells of the submandibular gland have distinct functions. The mucous cells are the most active and therefore the major product of the submandibular glands is saliva which is mucoid in nature. Mucous cells secrete mucin which aids in the lubrication of the food bolus as it travels through the esophagus. In addition, the serous cells produce salivary amylase, which aids in the breakdown of starches in the mouth. The submandibular gland's highly active acini account for most of the salivary volume. The parotid and sublingual glands account for the remaining.

Blood supply

The gland receives its blood supply from the facial and lingual arteries.[6] The gland is supplied by sublingual and submental arteries and drained by common facial and lingual veins.

Lymphatic drainage

The lymphatics from submandibular gland first drain into submandibular lymph nodes and subsequently into jugulo - digastric lymph nodes.

Nerve supply

Their secretions, like the secretions of other salivary glands, are regulated directly by the parasympathetic nervous system and indirectly by the sympathetic nervous system.

- Parasympathetic innervation to the submandibular glands is provided by the superior salivatory nucleus via the chorda tympani, a branch of the facial nerve, that becomes part of the trigeminal nerve's lingual nerve prior to synapsing on the submandibular ganglion. Increased parasympathetic activity promotes the secretion of saliva.[7]

- The sympathetic nervous system regulates submandibular secretions through vasoconstriction of the arteries that supply it. Increased sympathetic activity reduces glandular bloodflow, thereby decreasing the volume of fluid in salivary secretions, producing an enzyme rich mucous saliva. Nevertheless, direct stimulation of sympathetic nerves will cause an increase in salivary enzymatic secretions. In sum, the volume decreases, but the secretions are increased by parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation.[8][9]

Development

The submandibular salivary glands develop later than the parotid glands and appear late in the sixth week of prenatal development. They develop bilaterally from epithelial buds in the sulcus surrounding the sublingual folds on the floor of the primitive mouth. Solid cords branch from the buds and grow posteriorly, lateral to the developing tongue. The cords of the submandibular gland later branch further and then become canalized to form the ductal part. The submandibular gland acini develop from the cords’ rounded terminal ends at 12 weeks, and secretory activity via the submandibular duct begins at 16 weeks. Growth of the submandibular gland continues after birth with the formation of more acini. Lateral to both sides of the tongue, a linear groove develops and closes over to form the submandibular duct.[5]

Function

The submandibular gland releases a host of factors which regulate systemic inflammatory responses and modulate systemic immune and inflammatory reactions. Early work in identifying factors that played a role in the cervical sympathetic trunk-submandibular gland (CST-SMG) axis lead to the discovery of a seven amino acid peptide, called the submandibular gland peptide-T. SGP-T was demonstrated to have biological activity and thermoregulatory properties related to endotoxin exposure.[10] SGP-T, an isolate of the submandibular gland, demonstrated its immunoregulatory properties and potential role in modulating the CST-SMG axis, and subsequently was shown to play an important role in the control of inflammation.

Clinical significance

The submandibular gland accounts for 80% of all salivary duct calculi (salivary stones or sialolith), possibly due to the different nature of the saliva that it produces and the tortuous travel of the submandibular duct to its ductal opening for a considerable upward distance.[12] The submandibular gland is one of the major three glands that provide the mouth with saliva. The two other types of salivary glands are parotid and sublingual glands.[13]

Additional images

Mandible. Inner surface. Side view.

Mandible. Inner surface. Side view. Distribution of the maxillary and mandibular nerves, and the submaxillary ganglion.

Distribution of the maxillary and mandibular nerves, and the submaxillary ganglion. Mucus cell are identifiable by the lack of color in their cytoplasm, while serosal cells have a basophilic color.

Mucus cell are identifiable by the lack of color in their cytoplasm, while serosal cells have a basophilic color. Submandibular gland inflammation as seen on ultrasound

Submandibular gland inflammation as seen on ultrasound

Dissection images

Submandibular gland

Submandibular gland Submandibular gland

Submandibular gland Submandibular gland lateral view

Submandibular gland lateral view Submandibular gland

Submandibular gland Submandibular gland - right view

Submandibular gland - right view Submandibular gland - frontal view

Submandibular gland - frontal view Submandibular gland

Submandibular gland Muscles, arteries and nerves of neck.Newborn dissection.

Muscles, arteries and nerves of neck.Newborn dissection. Muscles, arteries and nerves of neck.Newborn dissection.

Muscles, arteries and nerves of neck.Newborn dissection. Muscles, nerves and arteries of neck.Deep dissection. Anterior view.

Muscles, nerves and arteries of neck.Deep dissection. Anterior view. Submandibular gland

Submandibular gland

See also

References

- Textbook And Color Atlas Of Salivary Gland Pathology Diagnosis And Management, Eric R. Carlson and Robert A. Ord, Wiley-Blackwell, 2008, page 3

- Asai, S.; Okami, K.; Nakamura, N.; Shiraishi, S.; Yamashita, T.; Anar, D.; Matsushita, H.; Miyachi, H. (2012). "Sonographic appearance of the submandibular glands in patients with immunoglobulin G4-related disease". Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 31 (3): 489–493. doi:10.7863/jum.2012.31.3.489. PMID 22368140. S2CID 35940244.

- Human Anatomy, Jacobs, Elsevier, 2008, page 196

- Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck, Fehrenbach and Herring, Elsevier, 2012, p. 155

- Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Bath-Balogh and Fehrenbach, Elsevier, 2011, page 135

- Ten Cate's Oral Histology, Nanci, Elsevier, 2013, page 255

- Moore, Keith; et al. (2010). Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7525-0.

- Koeppen, Bruce M. (2010). Berne and Levy Physiology 6th Edition, Updated. Mosby Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-07362-2.

- Hall, John E. (2006). Guyton Textbook of Medical Physiology, 11th Edition. Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-0240-1.

- Mathison, RD; Malkinson, T; Cooper, KE; Davison, JS (May 1997). "Submandibular glands: novel structures participating in thermoregulatory responses". Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 75 (5): 407–13. doi:10.1139/y97-077. PMID 9250374.

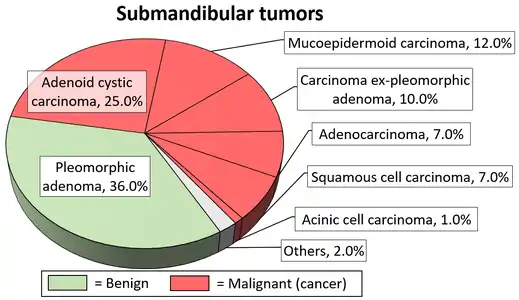

- Steve C Lee, MD, PhD. "Salivary Gland Neoplasms". Medscape.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Updated: Jan 13, 2021}}

Diagrams by Mikael Häggström, MD - Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Bath-Balogh and Fehrenbach, Elsevier, 2011, page 137

- "Submandibular Gland: Location, Function and Complications".

- Douglas F. Paulsen (2000). Histology and cell biology (4th ed.). Stamford, Conn: Lange Medical Books/McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-0593-7.

External links

- Histology at usc.edu

- Anatomy photo:25:10-0109 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Anterior Triangle of the Neck: Nerves and Vessels of the Carotid Triangle"

- Anatomy photo:34:09-0102 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Oral Cavity: The Submandibular Gland and Duct"

- cranialnerves at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (VII)

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Salivary gland infections

- Salivary gland cancer from American Cancer Society at http://www.cancer.org/cancer/salivaryglandcancer/detailedguide/salivary-gland-cancer-what-is-salivary-gland-cancer