Superior cervical ganglion

The superior cervical ganglion (SCG) is part of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), more specifically it is part of the sympathetic nervous system, a division of the ANS most commonly associated with the fight or flight response. The ANS is composed of pathways that lead to and from ganglia, groups of nerve cells. A ganglion allows a large amount of divergence in a neuronal pathway and also enables a more localized circuitry for control of the innervated targets.[1] The SCG is the only ganglion in the sympathetic nervous system that innervates the head and neck. It is the largest and most rostral (superior) of the three cervical ganglia. The SCG innervates many organs, glands and parts of the carotid system in the head.

| Superior cervical ganglion (SCG) | |

|---|---|

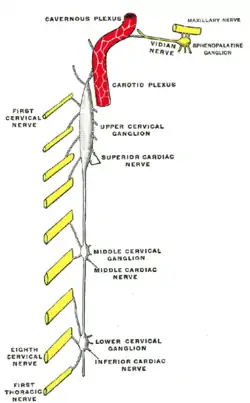

Diagram of the cervical sympathetic. (Labeled as "Upper cervical ganglion") | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | ganglion cervicale superius |

| MeSH | D017783 |

| TA98 | A14.3.01.009 |

| TA2 | 6608 |

| FMA | 6467 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Structure

Location

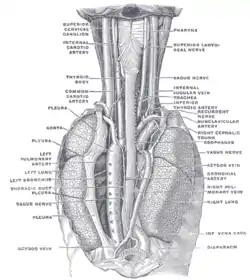

The SCG is located opposite the second and third cervical vertebrae. It lies deep to the sheath of the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein, and anterior to the Longus capitis muscle. The SCG contains neurons that supply sympathetic innervation to a number of target organs within the head.

The SCG also contributes to the cervical plexus. The cervical plexus is formed from a unification of the anterior divisions of the upper four cervical nerves. Each receives a gray ramus communicans from the superior cervical ganglion of the sympathetic trunk.[2]

Morphology and physiology and its neurons

The superior cervical ganglion is reddish-gray color, and usually shaped like a spindle with tapering ends. Sometimes the SCG is broad and flattened, and occasionally constricted at intervals. It formed by the coalescence of four ganglia, corresponding to the upper four cervical nerves, C1-C4. The bodies of these preganglionic sympathetic neurons are specifically located in the lateral horn of the spinal cord. These preganglionic neurons then enter the SCG and synapse with the postganglionic neurons that leave the rostral end of the SCG and innervate target organs of the head.

There are a number of neuron types in the SCG ranging from low threshold to high threshold neurons. The neurons with a low threshold have faster action potential firing rate, while the high threshold neurons have a slow firing rate.[3] Another distinction between SCG neuron types is made via immunostaining. Immunostaining allows the classification of SCG neurons as either positive or negative for neuropeptide Y (NPY), which is found in a subgroup of high-threshold neurons.[3] Low threshold, NPY-negative neurons are secretomotor neurons, innervating salivary glands. High threshold, NPY-negative neurons are vasomotor neurons, innervating blood vessels. High threshold, NPY-positive neurons are vasoconstrictor neurons, which innervate the iris and pineal gland.

Innervation

The SCG receives input from the ciliospinal center. The ciliospinal center is located between the C8 and T1 regions of the spinal cord within the intermediolateral column. The preganglionic fibers that innervate the SCG are the thoracic spinal nerves, which extend from the T1-T8 region of the ciliospinal center. These nerves enter the SCG through the cervical sympathetic nerve. A mature preganglionic axon can innervate anywhere from 50-200 SCG cells.[4] Postganglionic fibers then leave the SCG via the internal carotid nerve and the external carotid nerve. This pathway of SCG innervation is shown through stimulation of the cervical sympathetic nerve, which invokes action potentials in both the external and internal carotid nerves.[5] These postganglionic fibers shift from multiple axon innervation of their targets to less profound multiple axon innervation or single axon innervation as the SCG neurons mature during postnatal development.[6]

Function

Sympathetic nervous system

The SCG provides sympathetic innervation to structures within the head, including the pineal gland, the blood vessels in the cranial muscles and the brain, the choroid plexus, the eyes, the lacrimal glands, the carotid body, the salivary glands, and the thyroid gland.[1]

Pineal gland

The postganglionic axons of the SCG innervate the pineal gland and are involved in Circadian rhythm.[7] This connection regulates production of the hormone melatonin, which regulates sleep and wake cycles, however the influence of SCG neuron innervation of the pineal gland is not fully understood.[8]

Carotid body

The postganglionic axons of the SCG innervate the internal carotid artery and form the internal carotid plexus. The internal carotid plexus carries the postganglionic axons of the SCG to the eye, lacrimal gland, mucous membranes of the mouth, nose, and pharynx, and numerous blood-vessels in the head.

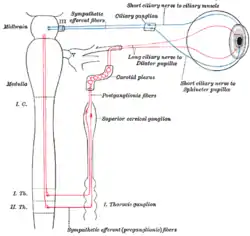

The eye

The postganglionic axons of the Superior cervical ganglion innervate the eye and lacrimal gland and cause vasoconstriction of the iris and sclera, pupillary dilation, widening of the palpebral fissure, and the reduced production of tears.[9] These responses are important during Fight-or-flight response of the ANS. Dilation of the pupils allows for an increased clarity in vision, and inhibition of the lacrimal gland stops tear production allowing for unimpaired vision and redirection of energy elsewhere.

Blood vessels of the skin

The postganglionic axons of the SCG innervate blood vessels in the skin and cause the vessels to constrict. Constriction of the blood vessels causes a decrease in blood flow to the skin leading to paling of the skin and retention of body heat. This plays into the fight-or-flight response, decreasing blood flow to facial skin and redirecting the blood to more important areas like the blood vessels of muscles.

Vestibular system

The SCG is connected with vestibular structures, including the neuroepithelium of the semicircular canals and otolith organs, providing a conceivable substrate for modulation of vestibulo-sympathetic reflexes.

Clinical significance

Horner's syndrome

Horner's syndrome is a disorder resulting from damage to the sympathetic autonomic nervous pathway in the head. Damage to the SCG, part of this system, often results in Horner's syndrome. Damage to the T1-T3 regions of the spinal cord is responsible for drooping of the eyelids (ptosis), constriction of the pupil (miosis), and sinking of the eyeball (apparent Enophthalmos; not truly sunken, just appears so because of the drooping eyelid).[7] Lesion or significant damage to the SCG results in a third order neuron disorder (see Horner's Syndrome: Pathophysiology).

Familial dysautonomia

Familial dysautonomia is a genetic disorder characterized by abnormalities of sensory and sympathetic neurons. The SCG is significantly affected by this loss of neurons and may be responsible for some of the resulting symptoms. In post-mortem studies the SCG is, on average, one-third of normal size and has only 12 percent of the normal number of neurons.[10] Defects in the genetic coding for NGF, which result in less functional, abnormally structured NGF, may be the molecular cause of familial dysautonomia.[11] NGF is necessary for survival of some neurons so loss of NGF function could be the cause for neuronal death in the SCG.

History

Reinnervation

In the late 19th century, John Langley discovered that the superior cervical ganglion is topographically organized. When certain areas of the superior cervical ganglion were stimulated, a reflex occurred in specified regions of the head. His findings showed that preganglionic neurons innervate specific postganglionic neurons.[6][12] In his further studies of the superior cervical ganglion, Langley discovered that the superior cervical ganglion is regenerative. Langley severed the SCG above the T1 portion, causing a loss of reflexes. When left to their own accord, the fibers reinnervated the SCG and the initial autonomic reflexes were recovered, though there was limited recovery of pineal gland function.[13] When Langley severed the connections between the SCG and the T1–T5 region of the spinal cord and replaced the SCG with a different one, the SCG was still innervated the same portion of the spinal cord as before. When he replaced the SCG with a T5 ganglion, the ganglion tended to be innervated by the posterior portion of the spinal cord (T4–T8). The replacement of the original SCG with either a different one or a T5 ganglion supported Langley's theory of topographic specificity of the SCG.

Research

Ganglia of the peripheral autonomic nervous system are commonly used to study synaptic connections. These ganglia are studied as synaptic connections show many similarities to the central nervous system (CNS) and are also relatively accessible. They are easier to study than the CNS since they have the ability to regrow, which neurons in the CNS do not have. The SCG is frequently used in these studies being one of the larger ganglia.[14] Today, neuroscientists are studying topics on the SCG such as survival and neurite outgrowth of SCG neurons, neuroendocrine aspects of the SCG, and structure and pathways of the SCG. These studies are usually performed on rats, guinea-pigs, and rabbits.

Historical contributions

- E. Rubin studied the development of the SCG in fetal rats.[15] Research on the development of nerves in the SCG has implications for the general development of the nervous system.

- The effects of age on dendritic arborisation of sympathetic neurons has been studied in the SCG of rats. Findings have shown that there is significant dendritic growth in the SCG of young rats but none in aged rats. In aged rats, it was found, that there was a reduction in the number of dendrites.[16]

- SCG cells were used to study nerve growth factor (NGF) and its ability to direct growth of neurons. Results showed that NGF did have this directing, or tropic, effect on neurons, guiding the direction of their growth.[17]

Additional images

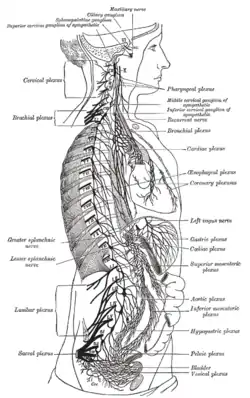

The right sympathetic chain and its connections with the thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic plexuses.

The right sympathetic chain and its connections with the thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic plexuses. Superior cervical ganglion

Superior cervical ganglion Sympathetic connections of the ciliary and superior cervical ganglia.

Sympathetic connections of the ciliary and superior cervical ganglia. The position and relation of the esophagus in the cervical region and in the posterior mediastinum. Seen from behind.

The position and relation of the esophagus in the cervical region and in the posterior mediastinum. Seen from behind. The Sympathetic Trunk and SCG innervation of target organs in the head.

The Sympathetic Trunk and SCG innervation of target organs in the head.

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 978 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 978 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Michael J. Zigmond, ed. (2000). Fundamental neuroscience (2 ed.). San Diego: Acad. Press. pp. 1028–1032. ISBN 0127808701.

- Henry Gray. Anatomy of the Human Body. 20th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1918 New York: Bartleby.com, 2000. http://www.bartleby.com/107/210.html. Accessed July 9, 2013.

- Li, Chen; Horn, John P. (2005). "Physiological classification of sympathetic neurons in the rat superior cervical ganglion". Journal of Neurophysiology. 95 (1): 187–195. doi:10.1152/jn.00779.2005. PMID 16177176.

- Purves, D; Wigston, DJ (January 1983). "Neural units in the superior cervical ganglion of the guinea-pig". The Journal of Physiology. 334 (1): 169–78. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014487. PMC 1197307. PMID 6864556.

- Purnyn, H..; Rikhalsky, O.; Fedulova, S.; Veslovsky, N. (2007). "Transmission Pathways in the Rat Superior Cervical Ganglion". Neurophysiology. 39 (4–5): 396–399. doi:10.1007/s11062-007-0053-2. S2CID 27184650.

- Purves, Dale; Lichtman, Jeff W. (2000). Development of the Nervous System. Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer Associates. pp. 236–238. ISBN 0878937447.

- Purves, Dale (2012). Neuroscience (5 ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer. p. 465. ISBN 9780878936953.

- Photoperiodism, melatonin, and the pineal. London: Pitman Publishing Ltd. 2009. p. 14.

- Lichtman, Jeff W.; Purves, Dale; Yip, Joseph W. (1979). "On the purpose of selective innervation of guinea-pig superior cervical ganglion cells". Journal of Physiology. 292 (1): 69–84. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012839. PMC 1280846. PMID 490406.

- Pearson, J; Brandeis, L; Goldstein, M (5 October 1979). "Tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in familial dysautonomia". Science. 206 (4414): 71–72. Bibcode:1979Sci...206...71P. doi:10.1126/science.39339. PMID 39339.

- Schwartz, JP; Breakefield, XO (February 1980). "Altered nerve growth factor in fibroblasts from patients with familial dysautonomia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 77 (2): 1154–8. Bibcode:1980PNAS...77.1154S. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.2.1154. PMC 348443. PMID 6244581.

- Sanes, Dan H.; Reh, Thomas A.; Harris, William A. (1985). Principles of neural development. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. pp. 214–221. ISBN 0-12-300330-X.

- Lingappa, Jaisri R.; Zigmond, Richard E. (2013). "Limited Recovery of Pineal Function after Regeneration of Preganglionic Sympathetic Axons:Evidence for Loss of Ganglionic Synaptic Specificity". The Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (11): 4867–4874. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3829-12.2013. PMC 3640627. PMID 23486957.

- Purves, D; Lichtman, JW (October 1978). "Formation and maintenance of synaptic connections in autonomic ganglia". Physiological Reviews. 58 (4): 821–62. doi:10.1152/physrev.1978.58.4.821. PMID 360252.

- Rubin, E (March 1985). "Development of the rat superior cervical ganglion: ganglion cell maturation". The Journal of Neuroscience. 5 (3): 673–84. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.05-03-00673.1985. PMC 6565020. PMID 2983044.

- Andrews, TJ; Li, D; Halliwell, J; Cowen, T (February 1994). "The effect of age on dendrites in the rat superior cervical ganglion". Journal of Anatomy. 184 (1): 111–7. PMC 1259932. PMID 8157483.

- Campenot, RB (1977). "Local control of neurite development by nerve growth factor". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 74 (10): 4516–9. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.4516C. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.10.4516. PMC 431975. PMID 270699.

External links

- Anatomy photo:31:07-0201 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center